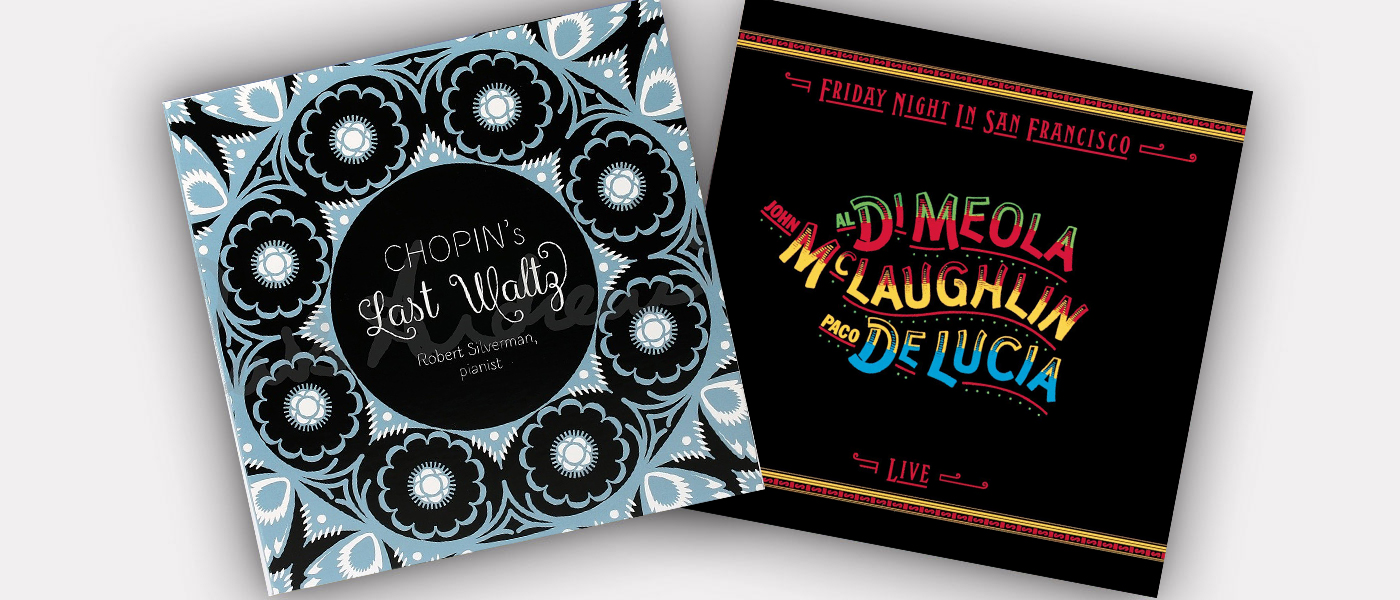

Music Matters Jazz (MMJ) closed their operations a while back, and although much of their work is still available online, the price has been juiced on titles that are presumably endangered. You will likely pay dearly for titles that are outright extinct, but there are still a handful of their records being sold at the original manufacturer’s suggested retail price of $40. We will look at a couple of those this month. Starting with The Big Beat by Art Blakey and the Jazz Messengers.

“The Chess Players” kicks things off while the contestants feel each other out with a call and response featuring the brass and rhythm sections versus Bobby Timmons on piano. Shortly, the song’s featured strategists begin the game within the game. Wayne Shorter’s tenor sax sits on the board’s right side, while Lee Morgan’s trumpet counters from the left. This configuration remains intact throughout the program. Shorter provides the muscle, Morgan the soul, while Blakey’s drumming is the obvious heart. I don’t say that simply because his name is on the front cover. I typically head for the bathroom during a live drum solo, but I would’ve worn a diaper if I’d been fortunate enough to catch Blakey in person. Hearing the MMJ version of “Sakeena’s Vision” might be the closest I ever come. Flowing through it all, Timmons and Jymie Merritt (bass) are this organism’s blood, filling the space with whatever it takes to make the whole thing fly.

“Politely” finds the band in an era of comparative tranquility, as the title suggests. I get a “Pink Panther” vibe from this one, and Morgan really shines here. “Dat Dere” is a Timmons composition, which gleefully cedes the spotlight to the horns for a time. When Timmons comes in, it’s to tickle, not to conquer. The MMJ mastering reveals his piano as the percussive device that it is. The hammers’ impact on the strings is felt more than heard, but it’s always there – even when the ensemble rejoins the fray to resolve the tune as a unit.

“Lester Left Town” serves as Shorter’s tribute to Lester Young who passed away about a year before the 1960 session that spawned The Big Beat. The song is as groovy as those that precede it, but my copy has two loud pops right in the middle of it. They are as incongruous in a MMJ record as a hooker at a Baptist tent revival. Not sure how they got in here, but they won’t wash away. It seems unfair to deduct a point from the sonic score for two brief imperfections, but MMJ has the disadvantage of being judged against their prior stellar work.

Secrets Sponsor

“It’s Only a Paper Moon” wraps the game up in an ornamental bow. Blakey takes another one for the road, and you can hear someone reacting vocally off mic during his solo. Maybe it was him. Laughing at his own jokes. His talent and feel is obvious, and I’d get a kick out of myself too if I had all that working within me.

This is the second MMJ record I picked up by Blakey, the other being the classic Moanin’. That one is a little more hard bodied, according to my ears. Both are phenomenal. Moanin’ is pricier. The wise choice would be to obtain both before costs get crazier.

And now for something completely different…

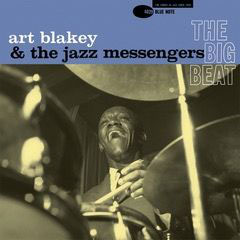

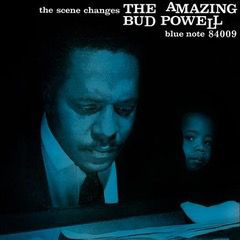

Impex recently reissued Legrand Jazz by Michel Legrand. It involves “Thirty-One of America’s Greatest Jazzmen featuring Miles Davis.” It also features way more instrumentation than I typically take with my Jazz. Like vibes. Which are especially vibrant and lively during “Wild Man Blues.” It’s like having prismatic bubbles bursting softly on your face. Or something. Herbie Mann plays flute on this one, and his is a name I recognize. Others are John Coltrane, Bill Evans, and Paul Chambers. All on one team. A different team involves a parade of trombonists along with Ben Webster and Hank Jones who both star on Django Reinhardt’s composition, “Nuages.” A quartet of trumpets and another quartet of saxes are on the third and final team of players, which includes Donald Byrd and Art Farmer playing a wild “Night In Tunisia.”

All of the players jump out of the speakers. There’s plenty of separation despite the size of the combos and the duplication of specific instruments. The players operate on a brilliant sound stage with great depth and balance. But they’re jumping off a dirty floor. There’s a persistent hiss throughout, and I don’t know where to place the blame. RTI’s pressing? Seems unlikely. The master tapes? I think the latter is most probable, but I have an RTI fetish. So factor that in.

The constant throughout this work is Michel Legrand as the conductor and arranger. He recorded this during a visit to NYC, but generally worked in his native France composing film and TV scores. Indeed, many of the pieces found here have a cinematic vibe, right up until the album closer. The last notes of “In a Mist” will give you whiplash. Like a car chase scene, that comes to a sudden, jarring halt. The entire Legrand program is an adrenaline blast, even for someone who prefers smaller jazz combos. I could quibble about the harp (not talking about a Blues harmonica here) intro to “‘Round Midnight,” but why? The productions are Ellingtonian in scope, and they mostly work just fine. Legrand was still in his twenties when he put this thing together in 1959, and he’s still working today. His talent is obvious and undeniable. Not sure that I need more than this one record of his on my shelf, but I’d love to learn more. Maybe I’m wrong…

Legrand Jazz was mastered by Chris Bellman on Bernie Grundman’s all-tube cutting system. I’d be curious to hear it in mono, but I’m happy to have it as is. I will give it a go when I’m in the mood for something busier than what I typically reach for. It’s like a craft cocktail in lieu of the usual whiskey with a splash of water. 3,000 of these were pressed, and they were advertised as being numbered, but mine is not. Comes in a sturdy gatefold sleeve with a “dramatis personae” on the back cover so you can follow who’s doing what. Sort of. If you can pick out one trombonist’s style from the other three in the same song, you should parlay that talent into something that pays. I’m satisfied to sit back and enjoy the big sounds. There are plenty in here…

Alright, back to the MMJ records. This was the finest vinyl reissue campaign that I’m aware of. Hell, it’s the greatest vinyl series that I’ve ever heard. I counted sixteen in my collection, and I mourn the titles I’m missing. The covers are as brilliant as the mastering, and every album feels like a revolving sonic treasure. If you ever have a shot at getting some of these at a decent price, do it. You will live a life of lonely regret if you do not. Like sleeping on a concert ticket’s sale date, then having to pay a scalper for admission to a show you can’t afford to miss. As alluded to previously, MMJ is no more. It was a fabulous run. RIP.

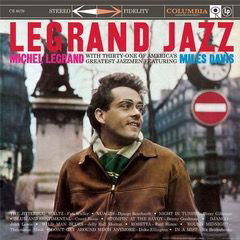

Bud Powell is an artist I was unfamiliar with until I picked up The Scene Changes about a month ago. Most online info on Powell focuses on his significant mental health issues, which required multiple hospitalizations, and were likely quite painful for the artist and those closest to him. It is probably safe to say that he was not the easiest person to collaborate with, but that’s conjecture on my part. It is not speculative to say that he was a badass pianist. That’s on full display throughout every Scene.

It seems that Powell was mentored by Thelonious Monk, speaking of challenging personalities. To my novice ears, Powell’s playing is more deft and fluid than his more well known tutor’s. That would make Powell the Michael Jordan of this analogy, and leave the more powerful, brutish Monk as our LeBron James. This comparison is not meant to inspire debates about which player is “better,” it is simply to illustrate the author’s perceived differences between the two men’s techniques. So relax.

The Scene Changes finds Powell accompanied only by Paul Chambers’s bass and Art Taylor’s drumming. Both “sidemen” were undoubtedly on top of their respective games while keeping up with Powell’s blazing speed, which had supposedly diminished by the time of this 1958 recording. That’s hard to fathom while hearing “Crossin’ the Channel,” but I’m no Jazz authority. I’d love to hear Powell’s earlier work as it’s been written that he was considered the “Charlie Parker of Piano.” Speed, indeed.

The MMJ presentation here is as clear and transparent as one might expect. So much so that it reveals Powell’s off mic scatting throughout the work’s entirety. This sometimes draws me away from the main story. Like a little fingerprint on your laptop screen, but way less annoying. The scatting strategy has certainly been employed since (Dr. Lonnie Smith), and probably before. It’s endearing in its way, and a distraction at times. I’ve dealt with weightier concerns, surely.

One of my favorite songs on The Scene Changes, “Danceland,” is followed up by one of my least favored, “Borderick,” which sounds a little like Christmas music. This kind of sums up what I imagine it would be like to work with a disturbed genius of Powell’s magnitude: Powell, Monk, and Parker all had their demons that pursued them. But perhaps sometimes they chased the demons too. If they transmuted their pain into beautiful music, that’s impressive. If they created despite the pain, that’s heroic. We are all deserving of compassion. From others, but especially ourselves. Treating your ears to the sounds of Bud Powell counts as self-care.

Last month’s look at John Coltrane with the Red Garland Trio led directly to this month’s Jazz Shootout. Analogue Productions (AP) has been going great guns with their Prestige reissue campaign for a while now. I, however, was too deep in the MMJ waters to hear much else. The reality of this harsh winter has spawned a beautiful spring, and I can now turn my full attention to these AP titles with the gusto they warrant. So here we go…

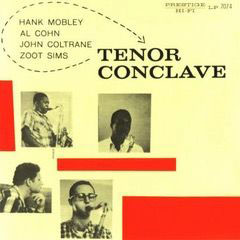

I’d been interested in Zoot Sims and Al Cohn since I discovered Kerouac (via Jim Morrison, I think) in high school. I hadn’t had much luck finding any of their recordings in an audiophile presentation, so discovering that both players could be found in collaboration with Hank Mobley and John Coltrane was a revelation. To find them together on an AP Prestige title seemed like providence. To learn that the Red Garland Trio provided the recording’s foundation was the proverbial cherry on top. It makes for quite a sonic sundae. It’s rich. Too sweet to be healthy.

The album is called Tenor Conclave, and it sounds like a million dollars. It’s the quietest disc I’ve gotten out of Quality Records Pressings. The liners are a little hokey, as Jazz liners often are, and these describe the alleged differences between the album’s sax descendants of Charlie Parker versus those of Lester Young. Whatever. The liners do break down which player is doing what during each song. Which is useful for the more studious among us and for those with sufficient command of the Jazz vocabulary (16 bars, chorus of fours, interlude…) to translate the message.

Secrets Sponsor

The record is a quick study as there are only two songs per side. This almost feels more like an EP, but there’s enough action for a box set. Everyone gets a time to shine without stepping on the others’ toes. Of all the players, Coltrane’s style seems the most distinct and the least predictable. Mobley’s playing is perhaps my personal favorite. Cohn and Sims are really great. I don’t know how else to say it.

The record is presented in glorious mono, as many of AP’s Prestige titles are. This is in contrast to the MMJ reissues, which focused mostly on the stereo mixes that the company preferred. Tenor Conclave plays out on a giant sound stage – deep and wide. You’d almost swear the Saxes were spread out left to right, but it’s an illusion. The detail is unbelievable with the Garland Trio floating just beneath the action before surfacing for air. They’re given ample room to breathe, and the listener’s focus and attention is rewarded without fail.

Having access to these AP titles takes some of the sting out MMJ’s departure. The takeaway in both instances is to capitalize when the opportunity presents itself. The records aren’t inexpensive. The AP titles hover around the $35 mark for a single disc release, which is about what you can expect in 2018 for an analog release from the original master tapes with Kevin Gray’s name attached to it. One hundred percent worth it for an audiophile’s ears. You never know when winter might arrive, and you never know what the next season brings. Now is always the time.

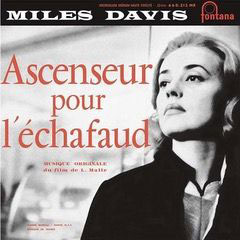

Miles Davis recorded the score for Louis Malle’s Elevator to the Gallows (Ascenseur pour l’echafaud, if you prefer) sometime around 1957 over the course of just two days. Malle is a French director, was only in his mid-twenties at the time, and invited Davis to compose the movie’s score around the time of a European tour that Davis was undertaking.

The film is a moody blast of noir-ish goodness starring Jeanne Moreau amongst others. But really just Jeanne Moreau. She was rumored to have been having an affair with Davis at the time. And she was rumored to have had an affair with Malle, but I don’t know the timeline. Regardless, she seems to have led a zesty life, and the camera knows she’s grand.

According to Malle, Davis screened the completed film a couple of times while taking notes. Then, he gathered a group of (mostly French) players to improvise the score during another screening. Maybe two. There’s video footage of at least one of the sessions that can be seen as part of some bonus materials on the Criterion version of their Blu Ray release. The “songs” illustrate the movie’s action. Or, more specifically, the mood of the movie’s action. There’s a zany stolen car ride that is as frenetic as it is implausible. There’s a musical representation of the titular stalled elevator scene, and there’s a lot of nighttime wandering around Paris while lost in the maudlin thoughts of Moreau’s unrepentant character. There’s a general disposition of sadness and ennui, and Davis spoke those feelings through his trumpet as if he were fluent in a language that Malle was just helping to develop at the new wave cinema’s dawn.

Like Tenor Conclave, Ascenseur pour l’echafaud is a quick listen. It’s presented as a reproduction of the original 10-inch disc, this time by Sam Records, a French company that did another cool film-related title by Thelonious Monk for Record Store Day last year. This is an all-analog project that was pressed at Pallas a couple of years ago, which is around the time I noticed that Pallas was no longer all that it once was. I stand by that assertion based on what I’m hearing on this score. Which is a shame because it’s a fine remastered with biting highs and syrupy lows that capture the movie’s ambience perfectly.

There’s a newer release on a different label, which includes outtakes, and alternate versions on two additional 10-inch discs. I didn’t think I needed all that, and I’m happy to have gone for the straight reproduction of the original release. Liners are included in the version we’re exploring, but they’re all en Francais. (There’s a black and white photo of Miles included, presumably from one of the sessions, which I can understand just fine.)

Both versions described above are readily available right now. I can’t speak for the new one, but Davis fans should at least explore this abbreviated version. The music demands it. And I would recommend the film to just about anyone. It’s a slow burner with some improbable plot devices, but nothing crazier than the current news. Check out the film and the score and decide for yourself. Bon appetite.