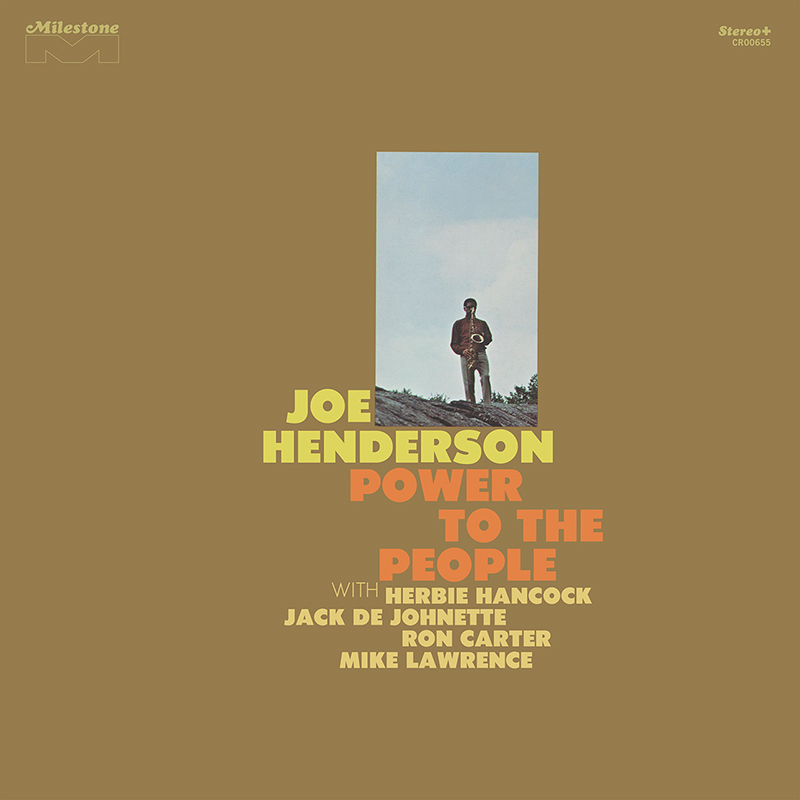

I had the good fortune of attending a show at the SF Jazz Center during a quick visit to the Bay Area last week. If you’re a Jazz lover, and you haven’t made it to “the first free-standing building in America built for jazz performance and education,” it’s worth the pilgrimage. Brandee Younger lit up the main room during my visit, but there’s a more intimate space for smaller productions called the Joe Henderson Lab off to the side. I’m always reminded of how much I’d have loved to see Henderson play when I visit the Center, so I was primed for Jazz Dispensary’s reissue of his Power To The People, which I dug into immediately upon my return to Las Vegas. The release is part of the label’s Top Shelf series, and it has all kinds of weight-bearing names attached to it, both from the players’ angle and the production team.

Henderson kicks the album off with a languid line on his tenor sax during “Black Narcissus” and is soon reinforced by some watery electric piano runs by Herbie Hancock (himself). Ron Carter both anchors and investigates with his stand-up bass while Jack De Johnette provides some rainy-day cymbal work with his brushes and all-around good taste. The tune sort of lures the listener in, feels like you’re dreaming in a poppy field until…

“Afro-Centric” blasts things into a whole ‘nother gear. This one’s freer form with the players, including Mike Lawrence on trumpet, scattering and peppering notes over De Johnette’s more forceful playing. Carter has switched over to the electric bass for this one and takes full responsibility for connecting the players with a more solid structure to latch onto. Hancock really shines for a while before the horn players return to a melodic theme that starts to disintegrate just as the jam fades out.

Power to the People flutters between and around a variety of styles, at times muscular, then reflective or pensive or outright narcotic (in the case of “Opus One-Point-Five,” with Hancock behind an acoustic piano locked into a deep meditation) during its 42-minute runtime. “Isotope” finds Henderson’s ensemble back in his Hard Bop glory that he debuted for Blue Note with Page One six years prior.

The title track is the album’s obvious centerpiece, and it gets the second side off the blocks with a stellar nine-minute groove that starts out swinging in the Bop tradition before getting weird. A kinetic frenzy with Hancock’s electric piano subtly distorting as a Fender Rhodes will when dialed in just so. Carter’s plugged in here too and the quintet really goes all in and achieves liftoff despite their mass, then resolves in a smooth landing with just an inch of runway left.

“Lazy Afternoon” is more traditional, and less provocative, but masterful in the hands of a quartet communicating on an astonishing level. “Foresight and Afterthought,” is the opposite of traditional, separated into “three movements” that feel like a workout. Invigorating and fatiguing. Challenging but agreeable. A sonic tightrope to send the listener to bed with more to consider than they might have anticipated if they, like the author, were previously familiar with only Henderson’s Blue Note work.

The playing on Power is formidable. Kevin Gray cut the lacquers and mastered the work so that the record’s significance can be experienced freely and directly with detail to scrutinize and air to breathe. RTI’s pressing is essentially flawless. And the disc is gloriously flat. This is a win in 2024. An all-analog victory. At this point, I trust the Top Shelf series to deliver a high-end product on par with any of the other, perhaps more renowned, audiophile releases from the likes of Analogue Productions, MoFi, or whoever, but with more of an eye towards titles that are historically less well-known. I’ll take that all day.

Secrets Sponsor

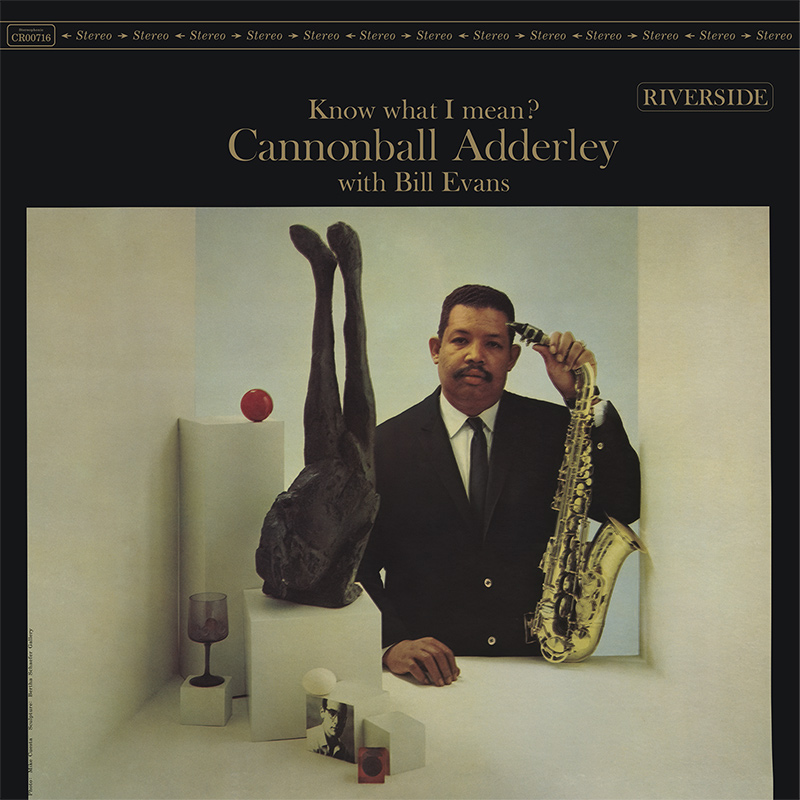

My time living in a world without a copy of Cannonball Adderley’s Know What I Mean? was dark. Hours became years. I survived earthquakes and pandemics. Presidents came and went, but none heard my plight. “Very Good+” copies of the Analogue Productions version sold for $150, then a sealed copy snuck passed me and jumped into the arms of a buyer for the low, low price of $95. Then, they jumped back into the $250 range. I was broken.

But just as darkness seemed destined to descend permanently upon the face of… me, Craft Recordings revived the Original Jazz Classics series. Master tapes were acquired, and Kevin Gray was hired. Then on March 1, 2024, I reached up from the Pit of Despair, grabbed hold of my vinyl lifeline, and filled my being with the sounds of this masterpiece. My life began anew.

Alright, that’s a bit much. Even for me. But the OJC series is a game-changing development for a lot of collectors. I’ve certainly enjoyed the titles I’ve acquired. None more so than this one. I mean, maybe the Sundays At The Village Vanguard reissue. Or Workin’ With The Miles Davis Quintet. I’ve had all of these on my list for ages, and to finally have acquired top-shelf quality versions that were all relatively affordable (certainly by 2024 standards) feels a bit like winning the lottery.

Know What I Mean? also stars Bill Evans whose playing is as compelling as Adderley’s, but a bit more subdued. His light is certainly not buried under a bushel, but Adderley’s candlestick is placed more prominently in the foreground. Adderley’s a bit louder in the mix, and his playing is more adventurous and bolder. Evans seems content to let Adderley chart a course while providing a responsive commentary that both supports and embellishes. Evans is the water, Adderley the topography through which it flows. The quartet as a whole allows the listener to just float downstream, a passive listen as rewarding as a more focused one depending on the recipient’s needs or intents.

“Toy,” in the leadoff slot on side two, provides a bit of a jolt, Adderley’s lines as playful as the title implies. The second half of “Nancy (with the Laughing Face)” emerges out of its cocoon to swing a bit more outwardly than one might expect too. But Know What I Mean? serves mostly as a decompressor. I always feel restored after listening, and mostly enjoy it alone. It’s not that I’m afraid others won’t like it. My friends have taste, after all. I just prefer listening intently to the exclusion of all else. It feels like an intimate record, and I choose to commune with it on my own. (We’re still talking about a Jazz record here, people. I promise.)

I was still 12 years from being born when Know What I Mean? arrived in 1962. I often wonder if Jazz players of the day might be compared to Golden Era Hip-Hop artists in that they both seemed to have upended convention and scared the hell out of older listeners. As I understand it, Hard Bop put the fear into fans of Big Bands like N.W.A. did my mom. In that way, I sometimes think of Adderley and Evans “featuring” on Miles Davis’s recordings from the late ‘50s before moving on to acclaim as formidable artists in their own right. Similar to Snoop Dogg’s introduction to the world via Dr. Dre’s The Chronic. On the one hand, it’s hard to reconcile anyone taking issue with Adderley or Evans or Rollins, or Roach. On the other hand, innovators often are made to run through a gauntlet of public rebuke before ultimately being recognized for their genius. And here we are.

I’m happy that I can explore my favorite eras of Jazz history in retrospect. Because, from where I’m sitting, all of these players are masters of their art. And the world is a better place for them having committed to the practice of their own spontaneous self-expression. To get to hear this record sound so alive and in such detail is no small gift. The pressing is stellar, the sounds are transparent, and the playing is consummate. You should get a copy too. There’s nothing to be afraid of. There never was. Know what I mean? (Yes, I do. I just snagged a copy for myself. Outstanding stuff! – Ed.)

Secrets Sponsor

Normally, I try to cover an array of releases from a variety of labels for this column, but Craft is on such a roll that I decided to go all in on their work this month. The astute observer will note that each of the three titles that we’re exploring in this installment is from three separate series detailing the work from three distinct labels. The Henderson title from the Top Shelf Jazz Dispensary series was originally released on Milestone Records, the Adderley/Evans disc from Original Jazz Classics on Riverside. And now we’re going to touch on Hot Buttered Soul by Isaac Hayes from Craft’s Small Batch series and originally released on Enterprise Records, a subsidiary of Stax.

And thank goodness it was. Because it almost wasn’t. Both Hayes and Stax were standing at a crossroads in 1969, Hayes having released a solo album that had bombed and Stax having lost their distribution deal the year prior. Despite the high stakes, Hayes was somehow given license to translate his artistic convictions into a type of Soul Music policy that would inform the following decade. Unfettered and without the label’s input. He turned his homework in on time. And we’ve been deciphering the code ever since.

I’ve lived the better part of 50 years by now, and I’ve come to appreciate Burt Bacharach, but it took me a second. Isaac Hayes was in his mid-twenties when he reinterpreted “Walk On By” in a way that would entrench the song in the American conscience both on its own and via the Hip-Hop producers that would sample it in a variety of settings and contexts for decades. The fuzz guitar, the swelling orchestral strings, Hayes’ inimitable vocal stylings. All of it coalesces into a sort of Funkadelic-adjacent Soul stew that crossed over in a way that Hayes’ more alien Detroit contemporaries couldn’t quite pull off until they changed their name, cleaned up their production values, and added a horn section.

The rest of Hot Buttered Soul is comprised of a scant three songs.

“Hyperbolicsyllabicsesquedalymistic” shares the first side with the Bacharach cover and gets deep in the veins with a Funk bassline that sounds like it’s made from molasses and some piano work that elicits grunts, exclamations, and sweat. The keys flit around the soundstage like Ali around the ring while the drums stay dead center and anchor the thing to the dirty Earth.

“One Woman” starts the second side with some loverman crooning and orchestral accompaniment, bringing the sweetness where there once was just a grind. At five minutes, it’s the shortest selection on the album by about another five minutes. Hayes’ translation of Jim Webb’s “By The Time I Get To Phoenix” occupies the rest of the work’s runtime and includes an extended spoken word intro that sounds slightly comical today, but likely made a certain subset of Hayes’ audience positively giddy in 1969. By the time “By The Time I Get To Phoenix” gets to grooving, time has warped, a sermon has slid past, and a low-key catharsis is imminent. There’s a build and an instrumental payoff, but it feels more like the cigarette after the act than the act itself.

According to Craft’s Hot Buttered marketing, “the original master tapes were sent to Bernie Grundman for all-analog mastering, where he utilized a custom tube pre-amp and analog mixing console with discreet electronics that were both made in-house, as well as a Scully solid-state lathe with custom electronics. Lacquers were sent to Record Technology Incorporated… for plating using their one-step process, where the lacquers are to create a ‘convert’ that becomes the stamper.” Very well. I’m stoked to have a few titles from this series, with last year’s Brilliant Corners by Thelonious Monk being a highlight of my collection as a whole.

But I gotta say that Craft is doing such fine work within the confines of their extensive and diverse catalog that I wonder if they could just get by absorbing their Small Batch series into one of the others. Or just press the Small Batch titles in the same way as their Top Shelf or OJC titles and call it something else. Because I have Eastern Sounds by Yusef Lateef from both the OJC and the Small Batch series, and they’re equally phenomenal. For most folks, $38 worth of phenomenal is going to be preferable to $100+ worth of phenomenal.

The completists will want both. It’s fun to obsess over the slightest differences in presentation, but overall, the detail and clarity are apparent across all three of the series that we’ve explored here. The instrumentation sounds so natural and present. The notes and tones housed in sonic bubbles provide such distinct separation and clarity. I’ll always be up for exploring all three, but I would probably avoid competing with myself by presenting the same title across multiple series. With a well as deep as the one Craft has dug, there’s enough to go around.