“We’re trying to express what’s happening in the world today as we – a new breed of young musicians – feel it. I mean the different tensions in the world, the ridiculous war in Vietnam, the oppression of poor people in this, a country of such wealth. The cats on this date usually discuss these things, but we’re all also trying to reach a state of spiritual enlightenment in which we’re continually aware of what’s happening but react in a positive way. The music in this album, you see, expresses strength – confidence that we’ll overcome these things.”

If I had been forced to guess which musician spoke these words, I’d have probably gone with one of Motown’s more conscientious Vietnam-era writers: Marvin Gaye or Stevie Wonder. If I’d had to kick the can further down the line, my third choice would likely have been Sly Stone. But I could have gone on forever without hitting on the right choice: Woody Shaw.

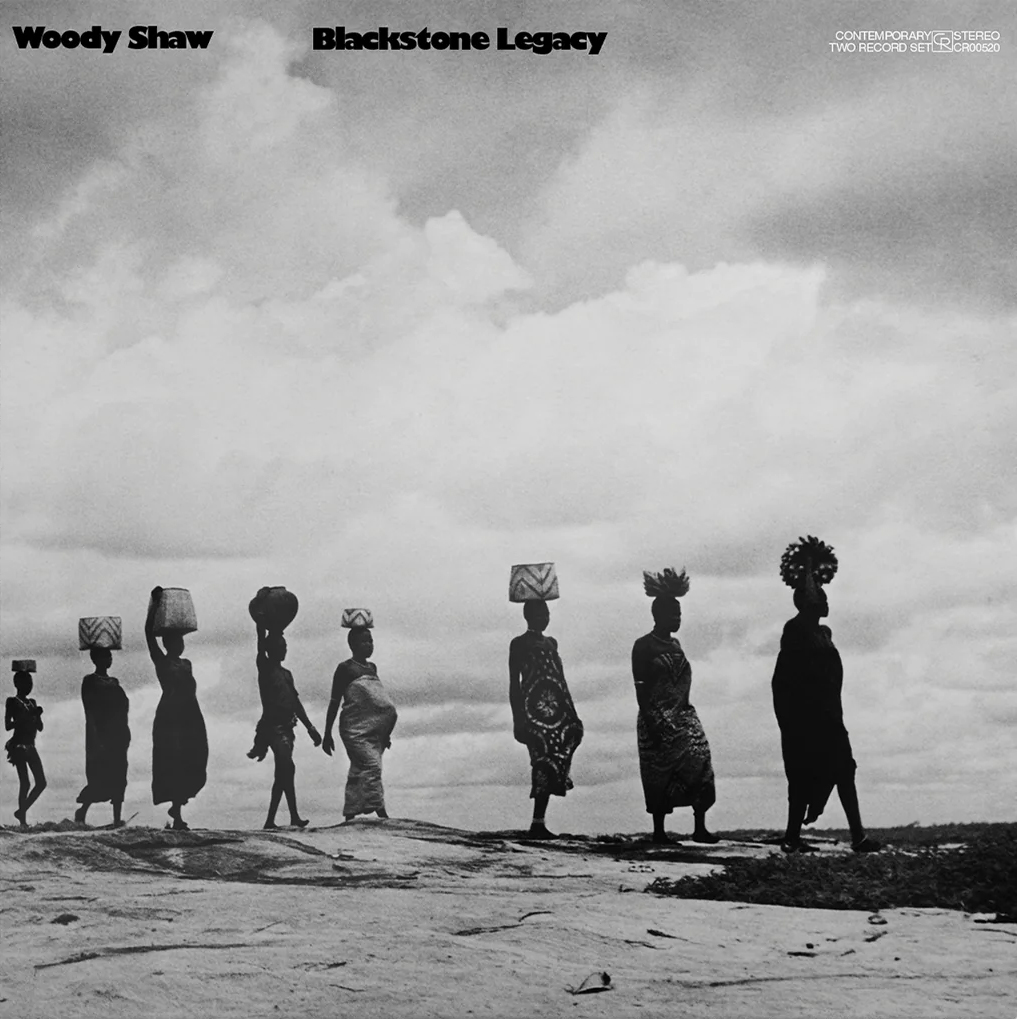

Until recently, I was only familiar with Shaw’s work in support of other artists in my collection. His playing on Larry Young’s Unity jumps off the platter, and his work on McCoy Tyner’s Expansions is certainly remarkable too. Honestly, I haven’t spent enough time with Eric Dolphy’s recent Record Store Day set, Musical Prophet, to write anything insightful, and I’ll be equally challenged to really get too deep into Shaw’s Blackstone Legacy today. It’s just too damn heavy.

I’m not kidding, man. This thing is going to take some time. Any listener who’s actually paying attention will know right away that they’re in the deep end. Shaw begins his statement piece, the title track and album opener, with a brief flourish to introduce his trumpet and his opus, and then things break loose for the entire first side. There’s tension and struggle, grinding and sweat. Blood, yes, and also moments to regenerate and probe and prepare for more striving and scrapping.

Would I have been as attuned to those sentiments without Shaw’s words in the gatefold liners to guide my understanding of what Blackstone Legacy meant to him? I certainly felt the power and the emotion on first listen even if I couldn’t identify the themes and the specific situations that the music was created to address. I’d listened to the record several times before exploring any of Nat Hentoff’s liners. I knew that things were generally hot, and also that there were intervals of cool, thank goodness, to ground me after having been sucked from the earth into the swirling, storming vortex that the players (Ron Carter and Gary Bartz amongst them) brewed up.

But I wouldn’t have known, specifically, that there were drum solos designed to represent Shaw’s feeling of confusion and self-doubt with subsequent melodies to indicate his increasing strength and confidence as an emerging artist (during side two’s closer, “Lost and Found”). But I’d have known that something was happening and that the “something” was too weighty for me to carry.

On all but two tracks, there are two basses (Clint Houston’s in addition to Carter’s) to anchor, but sometimes unmoor, the other instruments. There’s a tension that’s created, which is somewhat less obvious than the more overt cacophony of several horns blasting away at each other during the wilder moments. Similarly, George Cables’s piano work, acoustic and electric, can root the players (as he does during the middle portion of his own “Think On Me”) or push them to greater distances. Basically, any of these masters can serve as a compass or a Molotov cocktail, sometimes within the same composition.

Blackstone Legacy is a work of great complexity with plenty to explore from a cerebral standpoint, but it works most powerfully within the listener’s guts and chest cavity. I don’t know how long it would have taken me to find it were it not for the stellar work that the folks at Craft Recordings are doing, in general, and with regards to their esteemed Jazz Dispensary “Top Shelf” titles specifically. I mean, damn. They’re some of my favorite records that I’ve acquired over the last few years.

This one was pressed at RTI. My copy is flawless, flat, and silent. Pretty perfect. Craft confirms that it is an “all-analog mastering from the original tapes by Bernie Grundman who’s initials are evident in the dead wax. There’s nothing dead about the sonics though. The highs are surrounded by air, the mids are well-rounded and balanced, and the lows are defined and evident without overwhelming the others. If you’re following the Jazz Dispensary series, you already know. If you’re not, you should. Blackstone Legacy is a treasure.

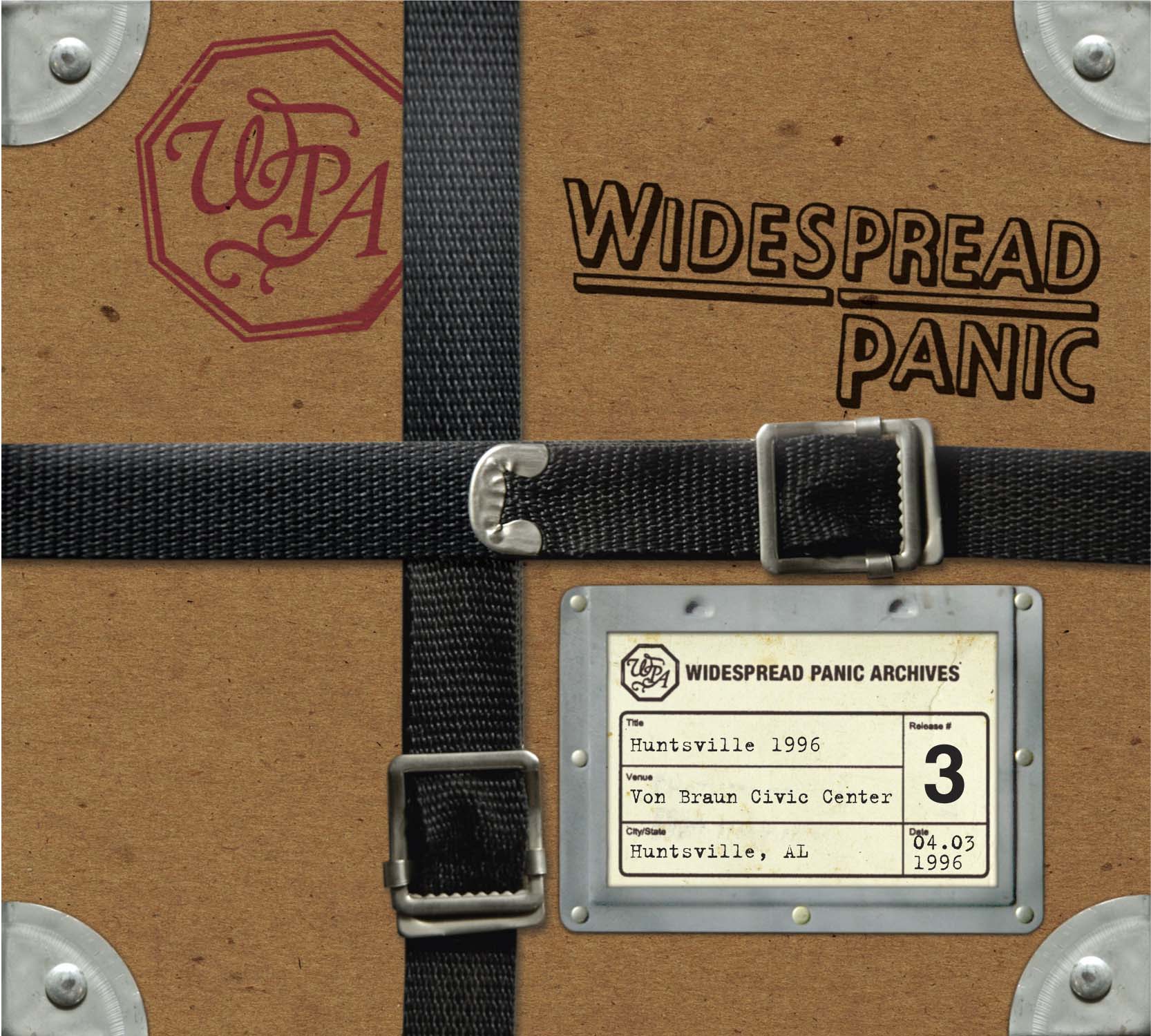

But, man, you should have been inside that shelter at the turn of the century. I was in Atlanta at that exact moment, and I halfway believed I’d walk out of the arena into a city beset by the cataclysm of the Y2K Glitch. Helicopters, searchlights, smoke, and destruction. Godzilla, maybe. The band had wiped out any fear I had though. My freshly blown mind just couldn’t contain much but awe at that point. WSP was a frigging high-octane, well-oiled Funk Machine by then, and they had been for a while. If you don’t believe me, or in case you’ve forgotten, you can check out their release from Huntsville 1996. That’ll set the (five vinyl) record straight.

Immediately and permanently.

Certain shows loom especially large in the band’s lore. I mean, there would be. There are literally thousands to choose from, all of them distinct. I wasn’t in Alabama for this one, I’d been to the two just prior. And I’m comforted by my recollections of shows that are stuck in my head decades later, but this one truly was special. Certainly, as a result of the setlist, but mostly the playing. The sextet had a rock belly full of fire, and the machine took on a collective mind of its own. A slow-breathing amoeba capable of swallowing the Earth in a backward black hole. Right from the jump.

The band’s fans constantly hope that the group will spring surprises on them. The true heads go in hoping for specific songs, calculating the likelihood of being satisfied based on when their desired tunes were last heard live. During certain eras, there would be no repeats over the span of at least three shows. Earlier this year (in Huntsville), they played a song they’d not performed since 1991 – a span of 2,591 shows. Not kidding.

Huntsville 1996 captures the band’s rare run through Scott Joplin’s “Solace” leading into “1×1,” a rocker their keyboardist, Jojo, brought from his prior band. Those bleed into a cover of Funkadelic’s “Maggot Brain,” a delicacy that I’d seen the band debut some years prior in Georgia, and certainly cringed at having missed in Alabama.

“Maggot” is an extended guitar solo. It was a vehicle for Eddie Hazel’s genius in the early ‘70s and for Michael Houser’s two decades later and on into the early aughts. Both players had tone’s mother in their back pockets always, but there are probably Funkadelic recordings that I could hear out of a passing car window without immediately being able to identify Hazel as the guitarist. Not so with Houser. He had the most distinctive tone I’d ever heard, and it was the only one he used. I miss his playing and the creative genius of his simplicity. May he always rest in peace.

He wasn’t resting in Huntsville, Alabama on April 3, 1996. He was tunneling. Exploring. Chopping down mountains with the side of his hand. His vocal turn on his original, “Vacation,” was another unexpected highlight right before the obligatory drum solo leading into the unforeseen romp through Dr. John’s “I Walk On Guilded Splinters.” Good night, America, I’d have cried for mercy, but that wouldn’t have left me any room for “Contentment Blues” or the show closer, Blind Faith’s “Can’t Find My Way Home.”

Throughout, the band plays with telepathic sensitivity. Dave Schools’s bass serves as both anchor and catalyst. The audience hangs on John Bell’s vocal explorations and mad-libs (“JB-isms”) at this and every show. The percussionists are the loosest, tightest section imaginable.

But we don’t have to imagine because these shows were all recorded for posterity. And this one was pressed lovingly on high-quality vinyl by Kindercore Records before they went under. My set has very minimal surface noise in only a couple of brief spots, and the records are all flat. Like the Earth after a Widespread rampage.

Everyone thinks their favorite “jam band” is different than all the rest. More nuanced and intentional. With more refined taste and greater depth. The only difference between me and everyone else in this regard is that I’m right. Huntsville 1996 is the proving ground.

I recognize that the decade has had its moment in the retroactive spotlight, that it’s considered cool by later generations just as the ‘60s were cool to those of us born in the mid-’70s. But I think that the ‘80s is the one decade wherein most all types of art took a significant hit to the groin. In general, I think that the emerging technologies were used to prop up rather than enhance or progress. Our collective taste seemed to tank, and – this is just me talking, here – the Golden Era of Rap came along to help alleviate some of that malaise.

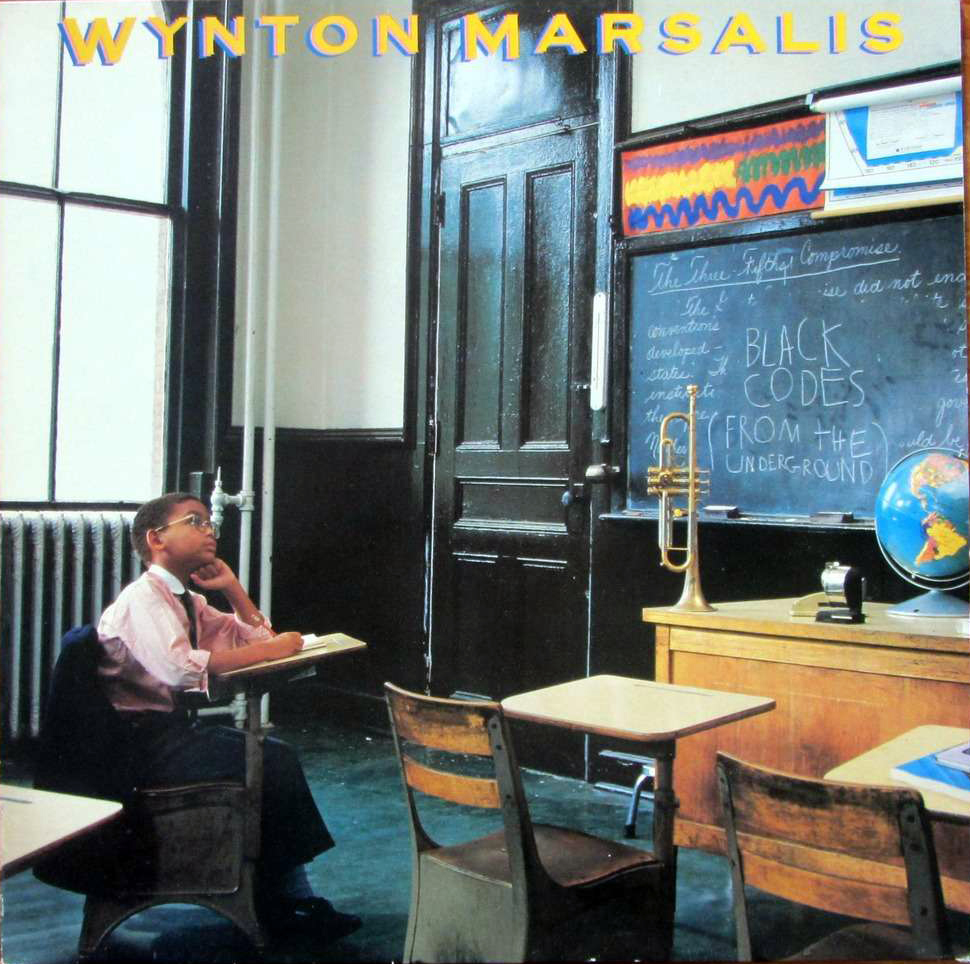

And so did Black Codes (From the Underground) by Wynton Marsalis.

I’d not heard it, or of it, until Vinyl Me, Please reissued it in August as their pick for that month’s Classics track. I do remember when Marsalis (Wynton, that is) was everywhere you looked, or listened, in the mid-‘80s, but I was too focused on what LL and them were up to. I remember being vaguely pleased by what I heard from Marsalis (my mom had a CD), but I was distracted by too many other things to get really involved.

And, knowing that Black Codes was originally recorded digitally, I almost passed on the album but decided to relax a bit and let VMP do their thing. The original idea was that they’d turn members onto albums they might otherwise have missed. Sometimes it works. Sometimes you get Usher in your mailbox. This time, they nailed it.

Not unlike Blackstone Legacy, one can immediately tell that Black Codes is working on multiple levels. The thing that was most confusing to me was that it was born in 1985. The production wouldn’t tip you off, and the performances certainly do not. It’s a little thin sounding in comparison to the Jazz recordings that I’m most familiar with. The playing is perhaps a bit more modern in the formally educated, more polished manner of the day. “Marsalis attended Juilliard, didn’t he?” (Extend the first syllable in “Juilliard,” leave the “r” sound out of the last.)

But don’t sweat the technique. Marsalis’s, and his band’s, is in the service of furthering the weighty emotions being expressed. His lines are often fluid, and melodic, but he’s not afraid to get down in the dirt either. His influences are apparent, he’s not really advancing the genre in any outward direction, but that’s sort of the point in this case.

Black Codes may have seemed reductive to the Jazz listeners and purveyors of 1985, but Jazz sounds in the ‘80s were mostly as diluted and sterile as any others. There were diamonds and pearls sprinkled throughout the wasteland, there always are. But my mind goes to the damn Manhattan Transfer or, God help us all, Kenny G when I think of ‘80s Jazz. David Sanborn, and “Smooth Jazz,” and all that. That’s what I had access to, anyway. I wasn’t in the clubs.

Marsalis may not have been inventing anything on Codes, but so what? There’s no harm in applying one’s skill and craft to a medium that’s already been developed or is in the process of developing. The White Stripes caught hell for the same reasons that Marsalis did, and now Jack White catches hell for getting too weird and venturing outside the confines of his sonic cage. Marsalis, according to VMP’s liners, was taking punches from the Jazzers of the day as well as the icons, but Black Codes plays as a top-flight Jazz album to my (aged) ears in 2023. The melodies are engaging, the rhythms are always precise, and the harmonies are solid. It’s as if the players melded into a single unit. And that’ll always be the dream for the rest of us.

VMP’s reissue of Codes is a DAA production. Mastered and lacquered by Ryan K. Smith and pressed at GZ. The sound is balanced and detailed, if not quite as heavy or visceral as some might hope. The pressing is mostly great, and my copy is mostly flat. I’m pleased with it, and you might be too if you give it a shot. I’m sure glad I did.