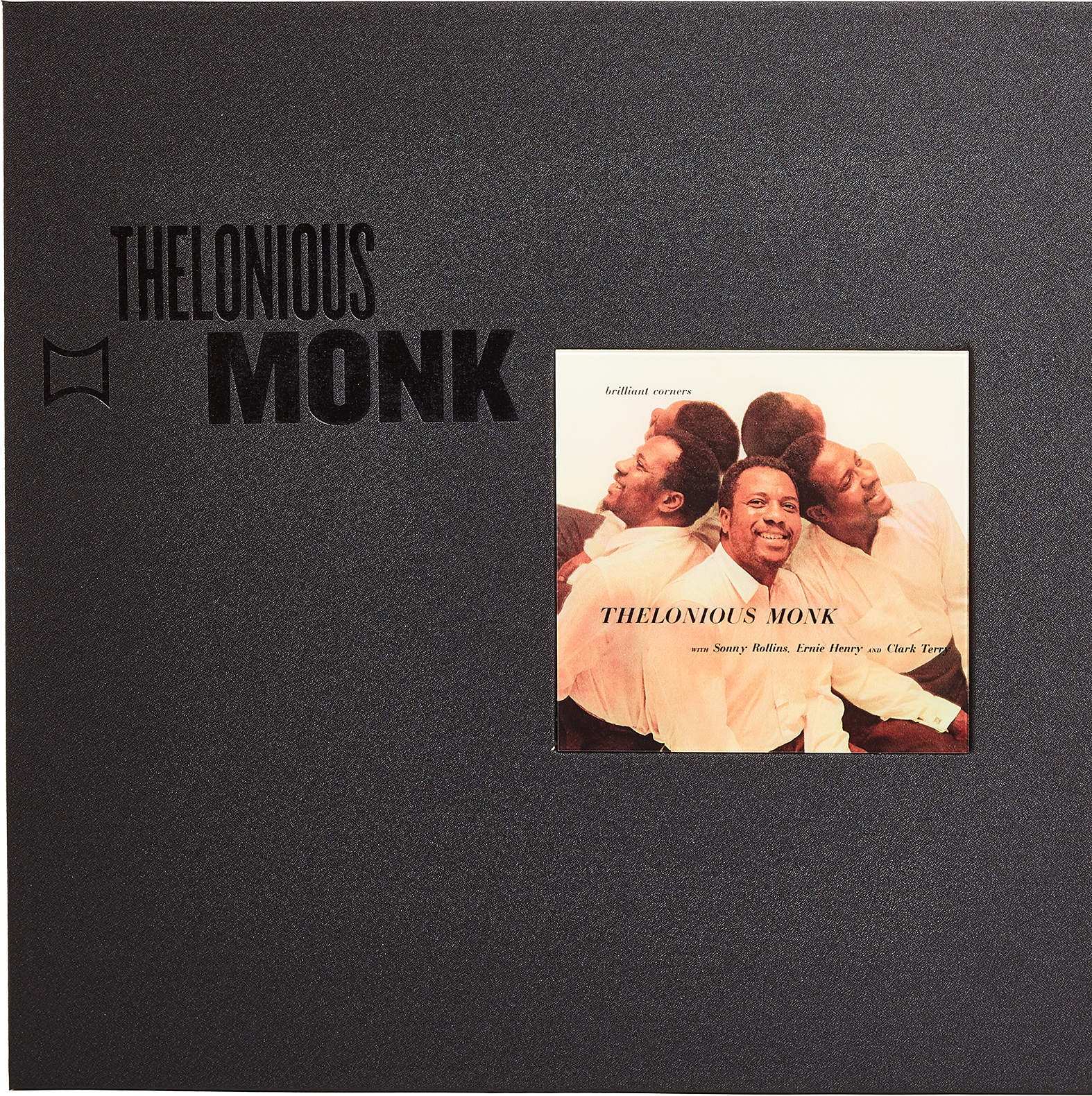

Thelonious Monk is having a moment. Another moment. It’s not that his position on the Mt. Rushmore of Jazz History was ever in question, of course. But, more than most, it seems that his weightier works are often made available in ways that will satisfy today’s most discerning listeners. Within the last few years, his albums have seen high-quality reissues by Impex, Mosaic, ORG, Pure Pleasure, Sam Records, and Vinyl Me, Please. There are almost certainly more, but I’m not sure that any of his works have been treated as respectfully as Brilliant Corners has been by Craft Recordings. That’s going to be a really high bar to clear.

Until Craft’s reissue, I’d been unfamiliar with Brilliant Corners because… I have a problem. I can sometimes be swayed towards or away from a recording based on the album artwork. On the one hand, it’s an admittedly shallow pool to play in. On the other hand, why make any effort with regard to cover art if there’s no marketing value in it at all? Unfortunately, I came of age during the era of Glamour Shots. Thankfully, I had none of my own, but they were everywhere during my teens. “Ubiquitous,” if you will. That might be what kept me away from Brilliant Corners for all these years. I assumed it was a cobbled-together posthumous release from the ‘80s or something. I’ve never been more wrong about anything. Had no idea how much musical meaning my life lacked before now.

Craft’s liners paint a portrait of the fraught sessions from 1956 that birthed Corners, and one could imagine the narrative applied to any album made under duress by the Kinks, or the Black Crowes, or any of Rock history’s more blustery bands. Two members of Monk’s quintet were replaced for the final of the three sessions after 25 tempestuous attempts to capture the title track in a single take. The album’s producer ultimately patched the final product together from multiple recordings, but none of that is obvious while listening. Even with the information available in retrospect, “Brilliant Corners” flows organically from start to finish, the stitching invisible to all ears. The band’s pulse is healthy – driving the engine with just enough juice to keep a steady pace without grinding any gears.

There’s a sensitivity between the players that seems innate as if one’s body is an extension of the others. This is especially remarkable since everyone came in cold to the material, the label not having had enough money to fund advance rehearsals. The four selections beyond “Brilliant Corners” were recorded in the traditional manner of the time, as far as we know. While the structure of “Corners” is segmented in such a way that building a Frankenstein of separate takes seems feasible, the remaining compositions wouldn’t be as forgiving of that type of wizardry. The solos roll into each other and flow together like distinct oceans expressing themselves as a single wave. A young Sonny Rollins plays like he was born on the captain’s deck with his horn in hand, and Max Roach keeps the ship on course and on time like a sonic compass.

Monk’s solo turn on “I Surrender, Dear,” the album’s only cover, anchors the second side. Hearing Monk play with this degree of presence and clarity is a gift that was almost missed. According to the liners, the sessions were completed with a few minutes of (pre-paid) studio time to spare so Monk was encouraged to toss off a solo take to fill that window. The whimsical run through Bing Crosby’s first hit leads directly into album closer, “Bemsha Swing,” which finds Monk responding to the quintet’s opening theme note for note before spinning off into a solo that bends the melody and structure such that it remains recognizable but wholly new with each pass.

Craft utilized their fancy pressing compound and a one-step lacquer process for this release. Couple all that with Bernie Grundman’s all-analog mastering and cutting, and you’ve got yourself one of the most compelling releases in recent history, and the most engaging listen from this series that I’ve heard, so far. The pressing is flawless, the record is flat. The tones are well-balanced, and absolutely nothing gets in the way of the listener’s communion with the material. Listening is the exact opposite of fatiguing. It is invigorating. Think of any luxurious experience that you’ve ever had, then apply that to your ears, and you’ll be hearing Craft’s Small Batch reissue of Thelonious Monk’s Brilliant Corners.

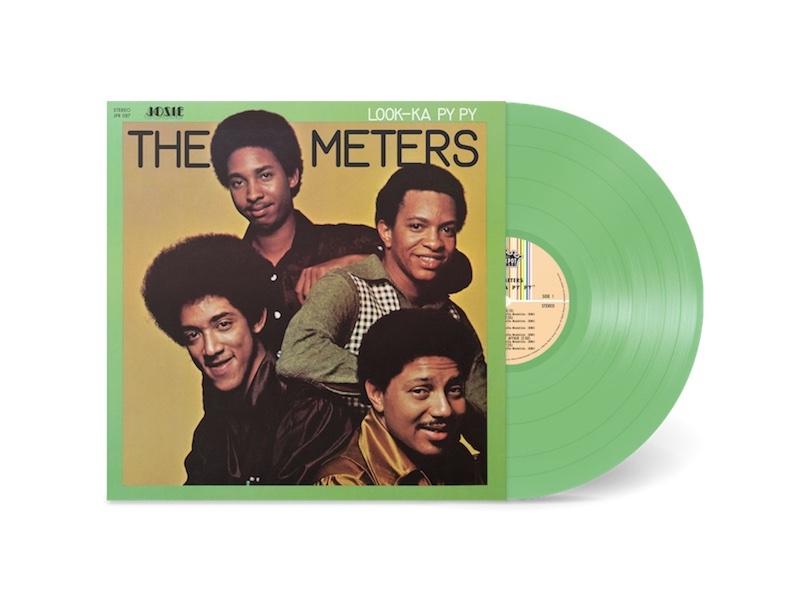

Not sure how long it would have taken me to find the Meters were it not for my having heard Widespread Panic’s cover of “Just Kissed My Baby” and “Ain’t No Use” back in the early ‘90s. That set me off on a pre-internet hunt that resulted in my purchase of the Funky Miracle double CD compilation from my local independent retailer in Augusta, GA. I remember being aghast at the price and buying the imported set anyway. “Strong choice,” as we used to say in the theater world. The comp contained almost all of the band’s first three records, and a few other singles too. I wore it out. Or it wore me out, more accurately. A high-water mark during my high school musical explorations, certainly.

Years later, in around 2005, I’d catch the original quartet in San Francisco at the Fillmore and have my mind blown all over again. The Funky Meters, with Brian Stoltz on guitar in place of Leo Nocentelli, were fun, but the original quartet was a whole ‘nother bag. Paul McCartney knew it, which is why he hired them as the entertainment for a Wings album release party in 1975. The Stones knew it too, which is why they invited the Meters out on tour later that same year and on into the next. And Dr. John and Robert Palmer hired the Meters to funkify some of their more successful recording sessions. The Meters were hip from the jump, daddy-o, and they remain so even after having finally disbanded. I got a fist bump from Nocentelli at a show last year, and my rhythm hand immediately improved ten-fold just from having made contact.

Recent years have seen an uptick in the availability of some well-made Meters wax too. Vinyl Me, Please released AAA takes on the stellar Rejuvenation and the (slightly less essential) Fire On the Bayou. Real Gone Music’s compilation, A Message From the Meters, sounds great and is even more comprehensive than the aforementioned Funky Miracle. And now, Jackpot Records has really stuck the landing with AAA reissues of the band’s first three records mastered by Kevin Gray. Fire on the bayou for real, y’all.

I mean, this is about as good as it gets. Really. “About as good” because all three of my records are slightly dish-warped. That’s annoying, but I defy anyone’s mood to remain foul once Look-Ka Py Py starts spinning. The title track was the first Meters recording that I ever heard, and the impression is still fresh over 30 years later. Everything about the Meters’ best work still is. The instrumentals, which are mostly what their first three records are comprised of, are especially revolutionary in their directness and simplicity.

It seems common nowadays for artists, mostly rappers, to build a lack of effort into their presentation. As if a lazy affect equals cool. Nah, man. Check out the Meters. Nothing on Look-Ka Py Py is rushed or strained. Everything is laid back and groovy. Deep in the pocket and thick with humidity. Nothing forced, the band cool while the jukejoint patrons undulate, grind, and sweat. Still, the talent and musicianship is undeniable. Nocentelli can shred. I’ve seen him do it. That’s just not what the best Meters material called for. And if it didn’t benefit the song, it didn’t get played. The strength comes from the open spaces, the missing notes. It results in a sort of leaning in on the listener’s part, an attempt to orient one’s self to a groove that is as unpredictable as it is straightforward.

Throughout, Zigaboo attacks from unforeseen, weird angles. There’s no way that he can stick the beat and hit the whacky accents and fills too, but he nails it every time. George Porter’s slinky bass lines build a solid floor for Art Neville’s organ to float above and crawl below while Nocentelli’s single notes, solos, and riffs kick the whole sound into an orbit around some funky planet that we didn’t even know existed. The planet, as it turns out, is New Orleans, and these grooves did much to form and inform that city’s rich musical history. One of America’s greatest cultural contributions. Period.

And these Kevin Gray cuts get all of that out of the original master tapes and into your listening room. The soundstage is tight, but not cramped. The tones are creamy and balanced. The details are crisp and there are sounds that revealed themselves to me for the first time after decades of listening to those import CDs. If you’re a Meters fan, this is your time. If you’re not, this is your chance.

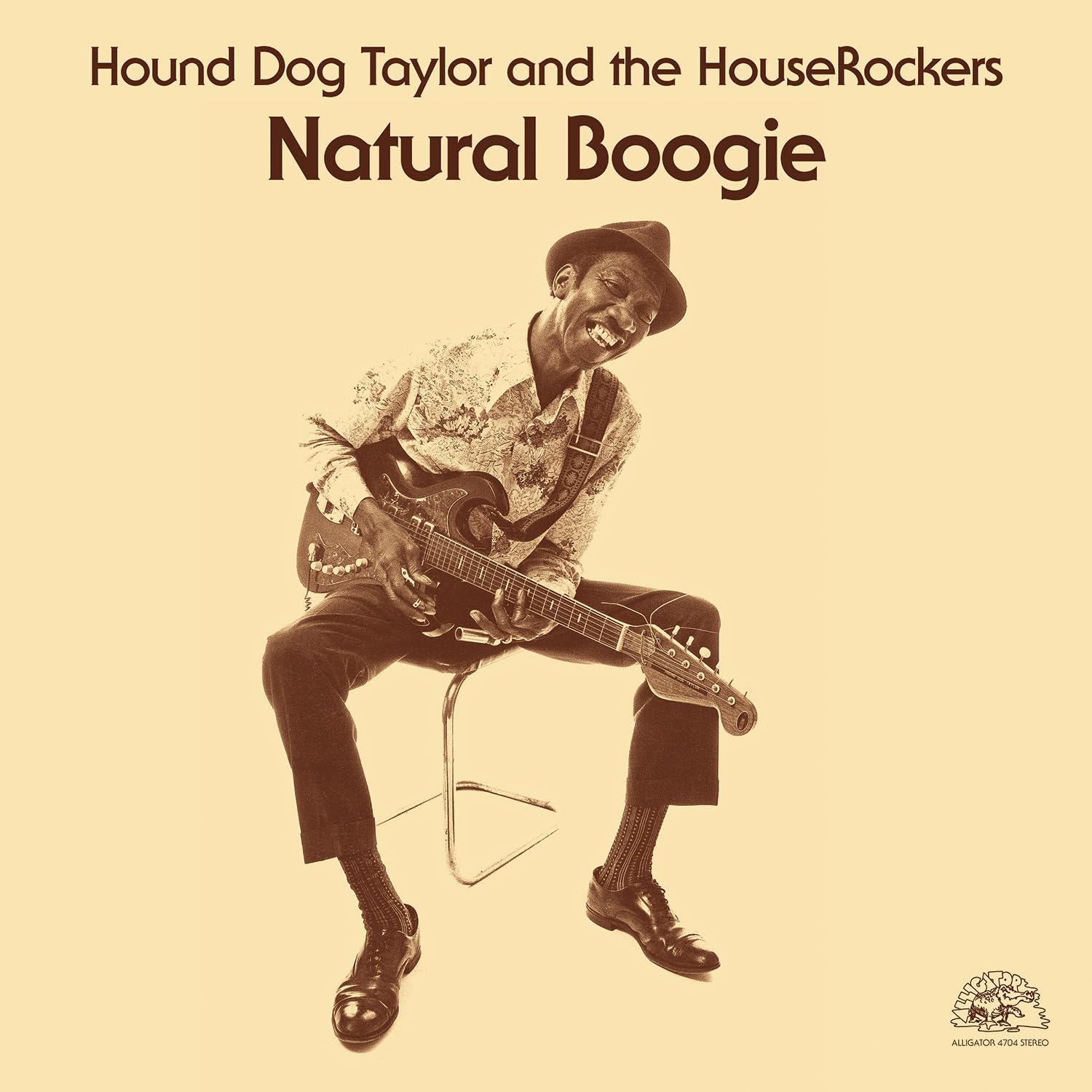

Those boys in the Widespread Panic band didn’t stop at turning me onto the Meters. If they had, it would have been plenty, but I also came to Fat Possum Records through Panic’s keyboardist who helped to get that label off the ground and in the air. He gave me an early cassette tape of Junior Kimbrough’s. From there, I got into R. L. Burnside, and his music is probably the biggest discovery I’ve made since the early ‘90s. I’d never heard anything like it. Burnside’s electric Raunch ’n Roll seemed to have sprouted straight out of the Northern Mississippi farmland fully formed with no prior context available or needed.

But I’d later learn of Hound Dog Taylor, a Chicago Bluesman whose band also omitted the bassist. They just commenced to blazing juke joints with two guitars, a drum set, and howling vocals. I was initially struck by the rawness and brute force of Burnside’s sound, the way his amps would break up in just the right way, and the way his vocals cut through the din to hit you square in the chest. Turns out, Hound Dog Taylor was in a similar bag back in the early ‘70s. Both men were active at that time, and both were toiling in obscurity. Both men would find success on a global scale towards the end of their lives, and both ultimately left legacies that will endure for as long as Blues music does.

Theodore Roosevelt “Hound Dog” Taylor was the first artist signed to Alligator Records and is still the most vital member of that roster for my ears. I remember coveting a Professor Longhair release on Alligator that I’ve yet to track down, and there is undoubtedly gold in them hills that I’ve not found yet, but I never paid a ton of attention to what Alligator had going on, in general. I’ve cherished my original pressing of Taylor’s Beware of the Dog for years, however, and now I have another of his titles to lord over courtesy of Vinyl Me, Please.

Natural Boogie is a show-your-work kinda calculation. It’s the opposite of polished. The players are light on technique. No one seems to really know much about what they’re doing behind the boards or in front of them. It’s forty minutes of straight-winging it in the studio, but at least there was a studio in which to wing. (Fat Possum would later cut that part out of the equation and just record from the juke joint floor.) And Natural Boogie is a Blues masterpiece. Taylor’s slide is out in front of the mix with his vocals not far behind. The other players are buried just a bit deeper, but Ryan Smith’s mastering presents everything in a flattering light with enough space for each member of the trio to shake, shutter, and shiver as the occasion requires. This one would clear the outfield wall at Wrigley Field and land several counties over. It’s a slam.

There’s no real need to get into a song-by-song breakdown here. The tunes cohere into a larger piece that mandates the listener’s attention throughout the entire runtime. No one is going to hunt and peck for songs on Natural Boogie. From the time the needle drops on “Take Five” until the last notes of “Goodnight Boogie,” the musicians brew up a party for your ears. If you’ve ever had the pleasure of attending a backroads Blues session, you’ll immediately be transported there. The producer’s goal was to record Taylor’s band as if they were playing in a Southside club, and he succeeded. The looseness is liberating. The cathartic release is palpable more than fifty years later. Two guitars, drums, and some singing are all you need to transcend this world for at least as long as the music plays.

VMP’s liners, which include an interview with Alligator label head Bruce Iglauer, reveal how remarkably cyclical things have been in the vinyl world over the last few decades. Iglauer describes starting Alligator on a shoestring in ’71 as a labor of love just like Fat Possum two decades later. He describes having to scramble to get a decent pressing of Boogie out into the world because he was booted from the pressing plant he used so that said plant could focus on getting the major label titles out into the world instead of Alligator’s. Indies face the same perils today, and it’s become increasingly difficult for lesser-known artists to get a record pressed when Taylor Swift’s latest gums up the presses for months at a time. The first run of Boogie pressings were defective with a visible flaw pressed through three songs. Today, finding a pedestrian pressing free of defects and warps is a cause for extended celebration – perhaps the kind that Hound Dog Taylor and his audiences were so renowned for.

But VMP got it all the way right on this go-round. This is party music presented in the most professional way. This would never have been considered an audiophile production, but the application of audiophile principles still pushes the release past what could have reasonably been expected for clarity of sound and immediacy of experience. If you’re looking for a good time, Hound Dog Taylor can help. There may never be a better time to get acquainted with his work.