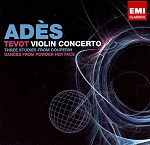

Antonio Lysy Antonio Lysy at the Broad: Music from Argentina Yarlung Records 27517

- Performance:

- Sonics:

This recording defines what the audiophile experience is all about. Producer Bob Attiyeh, who recorded both on analog tape and in high-resolution 176.4/24 digital format, employed a single mike, extremely short custom silver interconnects, and a customized tube preamplifier. There was no mixer in the chain. As a result, his analog-like master sounds remarkably close to the real thing.

Yarlung’s final product is available in several formats. While I reviewed it as a redbook 44.1/16 CD, pressed in Germany on a special alloy disc, it is also available as a download from linnrecords.com in either lossless 44.1/16 FLAC or high-resolution, 88.2/24 format. As such, it offers you the opportunity to compare the sound of your CD and computer playback systems. If the 88.2/24 download doesn’t sound better than the 44.1/16 CD mix, you know you have some work left to do.

This is anything but another of those audiophile recordings where the sound trumps the performance. The music and playing are marvelous, irresistible in fact. The great Alberto Ginastera’s Pampeana, Rhapsody No. 2, op. 21 begins with great force, as Antonio Lysy’s cello and Bryan Pezzone’s piano sing with equal eloquence. José Bragato’s famed Graciela y Buenos Aires, in which Lysy and bassist Pablo Motta team with the Capitol Ensemble, is all seduction. Ginastera returns with two of his Cinco Canciones Populares Argentinas, the deeply moving “Triste,†and the evocative “Zamba.â€

A special treat is Omaramor, a powerful cello solo by one of our finest contemporary composers, Osvaldo Golijov. Lysy makes his cello sound like a symphony, with plangent playing that betrays not a trace of buzz. Another stunning, very modern sounding cello solo by Ginastera, three works by Piazzolla (including the well-known Oblivion, in arrangements by Bragato), and a cello/piano closer from Lalo Schifrin make for the most engaging tour of Argentinean classical music I’ve ever encountered.

Antonio Lysy, son of famed Argentine violinist Alberto Lysy, currently chairs the string department at the UCLA Herb Alpert School of Music. He has concertized in Royal Fewstival Hall, the Concertgebouw, Tonhalle, Salle Pleyel, Wigmore Hall, Royce Hall, Sala Verdi, Berlin Philharmonie, and Teatro Colón, and worked under such distinguished conductors as Yuri Temirkanov, Charles Dutoit, and the late Yehudi Menuhin and Sandór Végh. Founder of the 12-year old Incontri in Terra di Siena chamber music festival in Tuscany, he has recorded extensively for CBC Radio, the BBC, Classic FM and other European networks. Although he isn’t well known in this country, his reputation is sure to grow once he finds more time for touring in the states.

Pianist Bryan Pezzone often plays with the Los Angeles Chamber Orchestra, LA Philharmonic, and the Hollywood Bowl Orchestra. Equally at home in classical and jazz, he has recorded music by Mel Powell and John Harbison. The Capitol Ensemble is well known in the LA music scene. As for José Bragato, who contributed both an original composition and arrangements, he is a cellist who toured with Piazzolla and often arranged for him when not busy performing with classical and tango orchestras and chamber quartets.

Bottom line. Great music, great playing, great recording. Available for download in CD and high-resolution formats. A winner all around.

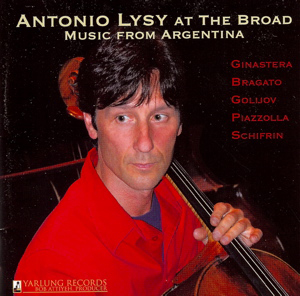

Catherine Russell Inside this Heart of Mine World Village 468092

- Performance:

- Sonics:

Catherine Russell is back. After a long and illustrious career as one of the best back-up singers in the business – she was one of the “coloured girls†who sang “Doo do doo do doo do doo do doo†on Lou Reed’s 1972 hit, “Walk on the Wild Side†– “Cat†has released her third solo album of irresistible tunes from earlier times. Beginning with Fats Waller’s classic “Inside This Heart of Mine,†the 12 tracks strut through an era when barbeque was king, brothers too were cats, whiskey ruled reason, depression was the name of the game, and music got your farther than the almighty dollar.

As rendered by Russell, who can transmit the spirit of this music like few others, these songs are much too good to be forgotten. Take, for example, “Troubled Waters,†scored by the Duke Ellington Orchestra for both Ivey Anderson and Mae West, or the never before covered “We The People,†which was premiered by Fats Waller. (“We, The People gotta have dancin’, plenty of dancing…). These are great songs.

One minute “Cat†is swingin’ in “As Long as I Live,†a tune by Ted Koehler and Harold Arlen; the next, she’s croonin’ in “November,†a touching ballad by Paul Kahn. The levels of insinuation and innuendo in “Just Because You Can†(“Just because you can doesn’t mean you should… Just because you should doesn’t mean you can. Oh if you can’t take make it got to lay back and take it like a manâ€) are only topped by the metaphors of “Long, Strong, and Consecutive.†If you don’t know what I’m talking about, or are too horrified to ask, it’s time to join the Christian Family Alliance. They have an answer for everything.

On Inside this Heart of Mine, vaudeville, blues, Tin Pan Alley, New Orleans, swing, jive, Delta-blues, and other styles rub shoulders, as Arlen, Ellington, Alec Wilder and other composers let loose. Many of these songs were originally performed by Duke Ellington, Peggy Lee, Maxine Sullivan, Howlin’ Wolf, Wynonie Harris, Fats Waller, Louis Armstrong, and Louis Russell. (Russell, who was Armstrong’s long-time musical director, was also Cat’s father). They’re really great.

They’re especially winners because Russell makes each and every song her own. It’s no wonder she won the German Record Critics’ Award in jazz. Her second album, Sentimental Streak, was called Vocal Album Of The Year in the 2008 Village Voice Jazz Critics Poll. Her back-up, New York players who know well the value of restraint, is as idiomatic and cool as it gets. We’ve got another winner here, folks.

“Slow as molasses, that’s how time passes, all the sleepy summer long.â€

“Kiss me long, strong and consecutive. No short snort will suit me, Jack. Long, strong and consecutive. Hold me close like aces back to back.â€

“It could be a spoonful of diamond, could be a spoonful of gold. Just a little spoon of your precious love, satisfy my soul.â€

God, how I love this stuff.

Versions of the following reviews originally appeared on sfcv.org, the website of San Francisco Classical Voice.

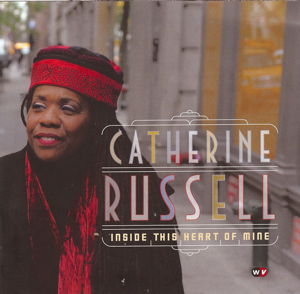

Michael Daugherty Letters from Lincoln E1 Music 7725

- Performance:

- Sonics:

To honor the 200th birthday of Abraham Lincoln (1809-1865), the 16th President of the United States, the Spokane Symphony under conductor Eckart Preu commissioned Michael Daugherty to write a Lincoln-themed work for baritone and orchestra. The piece, which was recorded live by E1 Entertainment (formerly Koch) on February 28 and March 1, 2009, was conceived as a vehicle for Thomas Hampson, a Spokane native who, according to the liner notes, “began his career with the Spokane Symphony.â€

Daugherty, who studied Lincoln’s writings and made trips to the Lincoln Memorial and Gettysburg battlefields, created a 27-minute, seven-section work whose text is drawn from Lincoln’s writings. The work begins with a musical evocation of Lincoln’s funeral train, jumps to a descriptive section from his autobiography, and ends with the Gettysburg Address. Along the way are two poems: “Abraham Lincoln is My Name,†written when Lincoln was a teenager, and “The Mystic Chords of Memory,†composed soon after he had turned 52. Most moving, besides the extraordinary Gettysburg Address, are the famed “Letter to Mrs. Bixby,†written to a mother who lost five sons on Civil War battlefields, and a prescient, two-line telegram to Mrs. Lincoln sent two years before his assassination.

If only Daugherty’s music were as moving as Lincoln’s words. Alas, he shows little evidence of the pictorial genius that has made the music of Prokofiev (as in “Peter and the Wolfâ€), Richard Strauss (try the Alpine Symphony and early tone poems for starters), and Mahler (on the march, on the battlefield, or opening the gates of heaven) so memorable. His Letters from Lincoln impresses as little more than a series of clichés. Big dramatic explosions, lots of cymbals, the folksy jig, clatter chime boom, snare drum rolls, death knell sounds, the trudging of troops, etc., etc. “Do you get the picture?â€, he seems to ask. Just in case, “HERE’S THE PICTURE.†At its most banal, the music verges on the pedantic.

In Daugherty’s liner note, he mentions that Lincoln fell in love with Anne Rutledge early on. It is believed that he never recovered from her untimely death from typhoid in 1835 at the age of 22. Seven years later, “Lincoln reluctantly married the high strung and temperamental Mary Todd, a decision that haunted him the rest of his life.†I can’t help but wonder if Daugherty knew so much about Lincoln’s gloom and darkness that he found himself resorting to musical clichés rather than writing music that revealed and illumined the emotional subtext of Lincoln’s words. Wozzeck this is not.

Hampson brings to the project all the vaunted sincerity, impeccable enunciation, and grandness of gesture we expect from him. Close to 54 at the time of the recording, the voice is grittier and more stentorian than of yore, yet retains a fair amount of its fabled beauty.

Presumably to bolster the Spokane Symphony’s reputation, the CD closes Anton Webern’s Langsamer Satz and In Sommerwind. Both works reside in “the outstanding collection of manuscripts from the Moldenhauer Archives established in Spokane with strong ties to the Spokane Symphony.†The performance lacks the touch of greatness.

John Adams Nixon in China Colorado Symphony Orchestra, Marin Alsop •Naxos 8.669022-24 (3 CDs)

- Performance:

- Sonics:

Those of us fortunate enough to attend Opera Colorado’s 2008 production of John Adams’ engrossing opera, Nixon in China, were swept to our feet by its cumulative impact. Given that the performance of soloists and Colorado Symphony Orchestra, under the able hand of Marin Alsop, and the Opera Colorado Chorus under Douglas Kinney Frost was witnessed by hundreds of the music and arts critics who had descended upon Denver for the 2008 National Performing Arts Convention, Alsop’s artistic triumph was all the greater.

The opera, a true collaboration between Adams and librettist Alice Goodman, focuses on the seven days in early 1972 that red-baiting President Richard M. Nixon (Robert Orth), his dutiful wife Pat (Maria Kanyova), and Secretary of State Henry Kissinger (Thomas Hammons, reprising the role he sang at the 1987 premiere) spent in China with Chinese revolutionary leader Chairman Mao Tse-tung (Marc Heller), his authoritarian wife and Cultural Revolution architect Madame Mao (Tracy Dahl), and Premier Chou En-lai (Chen-Ye Yuan). If the visit did not produce any major diplomatic breakthroughs, it nonetheless gave Adams and Goodman full opportunity to exercise their genius.

Adapting minimalist repetition to higher ends, the mechanical aspects of Adams’ music underscore the machine-like state militarism and diplomatic posturing of both countries’ leaders. Under those intentionally ceaseless and anything but tedious musical mechanics lies another layer, the personal. Here, Adams and Goodman use words, innuendo, and subtle changes in musical texture to reveal the humans behind their political masks.

In Act I, Scene 1, Orth as Nixon intentionally adopts an almost hectoring, stentorian tone to sing, “News, news, news, news, news, news, news, news, news, news has a has a has a has a kind of mystery, has a has a has a kind of mystery—y-y-y-y-y…†His shallow posturing plays to the TV cameras, and ignores Chou En-lai’s near futile attempt to introduce him to Mao. As the unstoppable orchestral repetition makes inescapable the political script that Nixon is playing out for all the world to see, the libretto questions the depth of his commitment.

In Act Two, the real personalities come to the fore. As Pat Nixon tours a Chinese glass factory, health center, pig farm and primary school, her arias reveal her values, vulnerability, and limits. (Her husband’s are obvious from the start). The Chinese don’t fare much better, as the ballet, The Red Detachment of Women, reveals the darker underpinnings of the revolution. As for Kissinger, the lech beneath the cartoonish mask serves as the ultimate object of revulsion..

Although the Nonesuch original cast recording, conducted by Edo de Waart, features SFCV’s own Stephanie Friedman as the Second Secretary to Mao, it’s important to note that it was recorded in either 1987 or 1988 (sources differ). Its early digital sound cannot compare to what current digital recording technique can offer. That makes the new recording indispensible. And the music, which benefits from the extra color digital advances bring, is fabulous.

Beethoven Piano Concertos 4 & 5 • Til Fellner, Orchestre Symphonique de Montréal, Kent Nagano ECM New Series B0034IULXQ

- Performance:

- Sonics:

Like the footsteps of a life partner, Beethoven’s music is heard so frequently that it’s easy to take it for granted. But listen to Austrian pianist Till Fellner’s ECM New Series CD of Beethoven’s Piano Concertos No. 4 & 5, performed with the Orchestre Symphonique de Montréal under Kent Nagano, and the love affair is renewed.

After Fellner’s brief entrance, Nagano’s orchestral introduction to the Piano Concerto No. 4 in G major melds lyrical beauty with grandeur. When the piano finally re-enters, its tender and graceful line bubbles over with melody. Fellner’s emotion is contained; he lets Beethoven’s dizzying scales and runs speak for themselves, without interjecting a surfeit of poetry. The expression comes more from the impeccably voiced notes themselves as from any special shading or rubato.

While this approach is certainly effective in more declamatory passages, Fellner and Nagano’s second movement Andante misses the mark. Listen, for example, to an almost 63 year-old recording from Clara Haskil and Carlo Zecchi, and you encounter an intense dialogue between an initially towering and emphatic orchestra and a dwarfed, reticent piano. In the course of five minutes, the piano slowly emerges, expressing its lament with such time stilling, aching simplicity that the orchestra bows to its eloquence. Pianists Wilhelm Kempf and Stephen Kovacevich also voice the Andante’s tender heartbreak in highly individual ways that take the breath away.

With Fellner, the tender core of Beethoven’s remarkable outpouring remains hidden. It’s as if he and Nagano have not found the means to together express the aching in Beethoven’s heart. The piano’s last notes are voiced so prosaically that it sounds as if the line trails off because Beethoven has run out of things to say. Contrast that to Kovacevich and Colin Davis’s ending, where the line dies off like the last lingering flickers of hope.

The Fourth’s marvelously emphatic finale, like much of Fellner and Nagano’s Fifth in E-flat major, aka the Emperor Concerto, is far more successful. Transitional passages, which in some hands are voiced with magical, almost diaphanous beauty, are approached in a more straight-ahead manner. But neither party has any difficulty speaking with strength and eloquence.

Louis Lortie, in his recent performance of the Fifth with the Leipzig Gewandhaus Orchestra, made his greatest impact in the second movement Adagio, which he played with ineffable tenderness. As in the Fourth, Fellner and Nagano go only so far. It’s almost as if they wish to insure that Beethoven’s softer side does not infringe on his nobility and grandeur. Their approach pays off in a thrilling final Rondo Allegro. But listeners who want yin and yang in equal measure will find themselves appreciating this substantial achievement, and then turning elsewhere.