Y’all, things are about to get fun. For me. Last month, we gave a listen to Lou Donaldson’s Mr. Shing-a-Ling, and I threatened to get back on the Music Matters Jazz train to check out some of the twelve titles in their latest series. I didn’t know what I was getting myself into. I ordered two, freaked the hell out when I heard how amazingly transparent and warm they were, then ordered six more. So, I have 66.6 percent of the series, and I doubt that I’ll be satisfied until I’m sitting on a hundred. I figured I might as well start with Blues Walk, again by Donaldson, to get a feel for the differences between this series and the Tone Poet records that Blue Note based on the MMJ discs. So… blastoff. Let’s get moving.

The most obvious difference between Mr. Shing-a-Ling and Blues Walk is that the former exemplifies Donaldson’s Soul Jazz phase (from the mid-‘60s) while the latter finds Donaldson knee-deep in the Hard Bop vein (from a decade prior). Shing-a-Ling is probably more accessible for Jazz novices, a point of entry for the uninitiated. It’s a little safer. The song structures are easier to discern, and the material is simply less intimidating for folks like me who appreciate Jazz but are not confident in our knowledge of the idiom. Blues Walk is something else. It is, in a word, masterful. If “Ode to Billie Joe” really is the most sampled song in Blue Note’s catalog, then people have been sampling the wrong stuff. “Billie Joe” lends itself much more readily to the Hip-Hop ethos than “Blues Walk” might, which is why it would be so pleasing to hear someone pull “Blues Walk” off right. Kendrick Lamar’s team should get crackin’ on this project with great speed and immediacy.

As the title suggests, “Blues Walk” is based on… the Blues. Right out of the gate, it sounds like it was informed by the Pink Panther theme song, but it pre-dates Henry Mancini’s tune by five years. So, there. The band’s pulse is mellow, but alert like the players had been meditating in a remote Buddhist monastery before entering Rudy Van Gelder’s studio. “Move” picks things up, and finds the quintet blazing away in the traditional Bebop aesthetic. The pulse has quickened, but the band is in complete control. Swinging away with the accuracy and strength of Cassius Clay in his prime condition. Generally, Donaldson’s three original songs are the bluest of the bunch. They find the sax man a little further from the freneticism of his hero, Charlie Parker. Donaldson’s phrasing is melodic and free. There are no restraints, just exemplary tastefulness, and technique. The man’s confidence is obvious, and why not? The album makes me want to pick up a horn and blow even though I do not know how. It fosters the creative urge. I know of no higher compliment to for an art piece.

Secrets Sponsor

And the sonics on this release are incomparable to the audiophile reissues from other labels. I’m going to take some of the suspense out of this scene and tell you right now that this will almost certainly continue to be the case for the other MMJ titles that we’ll be examining in the coming weeks. I don’t know how they do it, but the MMJ pressings are always as close to perfect as we can get in this Vinyl World. And Kevin Gray’s mastering is what we’ve known it was for years now. We have so much to look forward to. This one is my current frontrunner for reissue of the year.

Art Blakey and the Jazz Messengers released an album called A Night In Tunisia in 1957. They also released an album called A Night In Tunisia in 1961. Different record labels, different players, different songs, and artwork. No idea why anyone would do something so confounding, but we’re here for the second Night In Tunisia. The Blue Note one. The one that Music Matters Jazz just reissued along with eleven other masterpieces. The one that’s blasting from my stereo right now causing me to believe that there’s a raging Jazz quintet in my tiny studio apartment.

If Lou Donaldson’s Blues Walk is an engaging stroll through a verdant park with your sweetheart, A Night In Tunisia is a New York City cab ride. The kind that causes you to text your mother to tell her you love her just in case you don’t make it out alive. Blakey himself starts the party with a drum pattern that signals the main event is about to begin, then his band of young up-and-comers takes flight like they’re dropping bombs in the ring below. It helps that said up-and-comers had names like Wayne Shorter and Lee Morgan. And I might be losing my grip, but it sounds to me like Shorter enters the fray by playing the first few notes of the Flintstones theme song. That show was first broadcast the year before Tunisia’s release so the timeline matches, I just don’t know if the theme song was in place during the cartoon’s first season. Regardless, this all plays into my idea that Jazz was the Hip-Hop of its day. If I’m correct about the Flintstones snippet, then that’s a smart-assed interjection that stands in for old-time sampling. Decades before sampling was a real concern. The similarities don’t end with sampling, though. The Jazzers were pulling from a wide variety of inspirational wells including Classical, Blues, and (maybe) show tunes. Just like Hip-Hop producers pull from Jazz, Rhythm and Blues, and (probably somewhere at some time) show tunes.

The Jazzers were dirtying up their tones, pissing classicists off just like DJs were angering everyone except Herbie Hancock in the late ‘70s/early ‘80s by scratching and cutting up records. I’m trying to convey the idea that A Night In Tunisia feels like a group of young ‘uns gloriously and unabashedly exploring their art. Blakey’s Messengers are seen through the historical lens as a fertile breeding ground for players that would mature into the legends that they are today. And Blakey turned them loose, man. Anything goes with these cats. You can hear Blakey hollering off-mic in spots. Sounds like he’s imploring or encouraging or demanding or just blowing off steam. The performances are dynamic in that they come in sonic waves, sometimes splashing vibrant reds across the canvas that fade into deep blues before ramping back up into a kaleidoscope of colors and textures that seem to exist outside the frame. These performances stay with you long after the needle has found the dead wax. And that’s the only dead part of this disc, I can assure you.

But that’s not really true. Because the record itself is deathly quiet when it’s supposed to be. It’s a brilliant, clean canvas on which to splash those hues above and variable consistencies. When you’re finally allowed to come up for air during Lee Morgan’s “Yama,” you can hear the instruments rise up out of that silence to state their positions before decaying back into that void with all of the beauty and brilliance of life itself. This record lives, man. It’ll bite and scrap and claw. You might want to text your mom before you take this ride.

I remember seeing “The Low Spark of High Heeled Boys” printed in the setlist section of Widespread Panic’s short-lived newsletter in the early ‘90s. (When I say “printed” I mean exactly that. People used to print things on paper, then affix postage to the documents, then put them in a mailbox so that they might be delivered to readers on another day. Crazy.) I’d never heard the song, didn’t know if it was a cover or an original, but I knew I wanted in on the action based on the title alone. It didn’t take me long to learn that the song was by Traffic, a band for which Steve Winwood sang lead. I knew him as the guy on MTV hollering about a higher love with Chaka Khan in the mid-‘80s. So I was confused. But only momentarily. Traffic would become and remain, one of my favorite ‘60s era bands that I’d rarely think to listen to. But when I did, I’d reach for my original copy of The Low Spark of High Heeled Boys. Now, I’ll likely reach for the reissue that we’re here to explore.

Because it was “mastered by Joe Reagoso from the original Island Records tapes” with Kevin Gray. It was that last bit that caused me to jump. There’s a little wiggle room in that description, right? It was mastered from the original tapes, but were there any digital components introduced during the process? I tend to doubt that this is an AAA title, but Kevin Gray’s imprimatur carries me a long way in this whacky world of vinyl. I mean, I don’t even know what his role was in this release. Only that it was remastered with him, not by him. Whatever. It sounds pretty great, and I also have the original with which to perform a side-by-side shootout. So that’s exactly what I did.

And here’s what I found: neither the original nor the reissue are especially three-dimensional. All of the action is right at the front of the stage. Both versions involve instrumental accents that are precisely placed in the corners with the heavy maneuvering in the middle. The original has a little more air in the high end. The reissue carries more sonic information, in general, and certainly demonstrates greater bass response. My original pressing is damn near flawless, especially considering it’s older than me (I’m 45), and the new pressing is too. Hats off to Rainbo Records for that. The Friday version is blue. The reissue recreates the original album cover art, which involved clipping off two of the cover’s corners to create the illusion of a cube. Yay cubes.

And the music on this disc is exemplary. Traffic was renowned for bridging classic and progressive Rock stylings with Jazz and improvisatory techniques. “Hidden Treasure” starts things with a traveling-minstrels-in-the-enchanted-forest vibe, but it’s still good. I’m just not that crazy about the flute as a Rock instrument. The title track is next, and it showcases the Hall of Fame band’s chops from a million different angles. “Light Up or Leave Me Alone” is another highlight as is “Rock and Roll Stew.” It’s pretty perfect. If you’re uninitiated, this would be a fine place to start due to quality of sonics, performance, and general coolness.

I spent the bulk of my early youth sitting in front of the television staring lifelessly at one of two Motown specials that I’d recorded on VHS tapes. Michael Jackson debuted his moonwalk during the Motown 25 telecast from 1983, and that changed every damn thing. All sorts of fun things happened during Motown Returns to the Apollo which aired in May of 1985, including Boy George duetting with Stevie Wonder on “Part Time Lover,” which wouldn’t be officially released until August of that year. One of the two specials, I can’t recall which, involved footage of Cab Calloway performing onstage with an orchestra the size of Manhattan. I didn’t know what to think about that guy. His overwrought mannerisms freaked me out. He looked like he could collapse from exhaustion at any second. The garish sight of his hair hanging down in his face contrasted with his formal attire. Was that a tuxedo or a Zoot Suit? And what the hell is a Zoot Suit? Anyway, the images stuck with me for as long as images can. They’ve long since begun to fade, but I saw that Pure Pleasure did a reissue of a Calloway album recently, so I decided to stick a toe in that water. I still don’t know what to think about that guy.

And I’m still a little bit on the fence about whether or not grainy recordings that were initially released as 78s are worthy of the audiophile treatment. I guess some are, but it’s still a little disorienting to hear all the hissing and ticks that are ingrained in the recordings themselves while you’re trying to decide if all that noise is a defect in the actual record that you just purchased. I’d imagine that removing the hiss would sap some of the life from the recordings too. That’s certainly been the case with regards to the 8 billion Robert Johnson reissues and remasters that Columbia has trotted out since 1990. But the Calloway recordings are a lot less raw than the Johnson stuff. The Calloway recordings were made between 1933 and 1945, the compilation of the recordings that we’re exploring was released as a long-player in 1956. Johnson’s sides were recorded in 1936 and 1937, so the timelines overlap, but I’m guessing that Calloway’s sessions were a little more formal with a lot more money behind them. If that’s true, it makes sense that a reputable company like Pure Pleasure could work a little more magic with the Calloway material, which was almost certainly marketed to a national audience, than they could with the regional sides that obscure Blues musicians were making in the Great Depression. Or maybe I’m talking out of my ears when I should just be listening through them.

Because listening to this record is a lot of fun. Some songs have aged better than others, but that’s how it goes. I cringed when I recently watched the opening to Eddie Murphy’s Delirious stand-up for the first time since the Motown 25 era. I had a similar reaction to Calloway’s “Chop, Chop, Charlie Chan.” But “Blues in the Night” is a frigging romp, and of course “Minnie the Moocher” is timeless. If you’re interested in a strange hybrid of Big Band Swing, comedy, and Vaudeville, then I’d imagine Cab is your guy. And there’s probably no moonwalk without Calloway’s Zoot Suit. Pure Pleasure masters from the “best available sources,” not necessarily the original tapes. I doubt that Cab will ever sound much better than he does here, but there’s only so much you can do. Go in with your ears open.

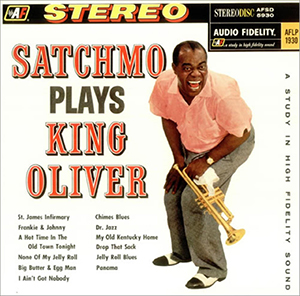

New Orleans style Jazz is a joyous sound, huh? I caught the Preservation Hall Jazz Band at the SF Jazz Center a couple of weeks ago, and I spent the entire evening looking like a glazed ham. Far away eyes with a dullard’s smile smeared across my face for at least 90 minutes straight. But as enamored as I am of the sound, I have precious little New Orleans Jazz in my vinyl collection. After catching the Prez Hall show, I vowed to remedy that ASAP. And I started with Louis Armstrong. Because apparently everything starts with Louis Armstrong. “Satchmo” if you prefer. I read a book on Jazz appreciation recently that credited Armstrong for inventing Jazz phrases that are still in use today, and I’ll buy that hook, line, and sinker.

All day long. If for no other reason than because I’ve heard as much from Jazz aficionados for what seems like forever. I mean, it’s generally accepted that Armstrong blazed the path for Jazz to become the worldwide phenomenon that it’s been for decades. The book’s author also set forth the idea that Armstrong has influenced “countless performers in other idioms” as well. The issue for me is that I was born in 1974, so I’ve never known a world that hadn’t already absorbed Armstrong’s influence before my arrival. I’ve dealt with this before. Never really been able to pinpoint Buddy Holly’s influence on Rock ’n Roll either. But I digress. We’re here to check out Satchmo Plays King Oliver. So, let’s do that.

Secrets Sponsor

King Oliver was the pioneering Jazz man that mentored Armstrong, the language’s most revered pioneer of all. Some of the songs on Satchmo Plays King Oliver would be recognizable by name to even passive appreciators of Jazz. At least those of a certain age. “Saint James Infirmary,” for example, is represented on the second album that we’ve explored at Secrets this month, the other version belonging to Cab Calloway. “I Ain’t Got Nobody” will be recognizable to anyone who came of age in the ‘80s while watching MTV because none other than Diamond David Lee Roth had an unavoidable hit with it then. And there are as many versions of “Frankie and Johnny” as there are ham-faced smiles at a Prez Hall show. That one is especially zesty on the Satchmo Plays record on account of the saloon-style piano accompaniment throughout. But my favorites are the instrumentals. We all love Satchmo’s vocal stylings whether we like it or not. If you don’t, you probably kick puppies for fun. But, for my Mardi Gras beads, the instrumentals convey unbridled good times without the distraction of a lyrical message or story. If you’re not having fun during this listen, you should check your pulse. You might be in line for a Jazz Funeral.

These elderly recordings are gloriously clear. There’s an “in the room” feel, especially with regards to the vocals, that surprised me. Pleasantly. The stereo presentation is a little off-putting at times, but that’s just a matter of preference. I’d love to hear the mono version. Here’s where things get wobbly: my pressing ain’t great. There are clicks and ticks, and tocks and pops sprinkled throughout the first side. I am still not all the way on board with Quality Record Pressings. I think they’ve improved, but I think they’re overrated. Their mastering is typically brilliant. Their packaging superb. But you can’t hide from a dirty pressing. And QRP still can’t seem to find any consistency with regards to that. They’re hot and cold. New Orleans Jazz should just be hot. The search continues…