In my last installment, I looked at the best recordings on LP and CD of Nielsen symphonies from the start of stereo issues (1963) to the 125th anniversary in 1990. I will now proceed to look at the important recordings, in my biased and not well-credentialed opinion, of what is best currently. Over 25 CD box sets exist. I could not listen to all of them, but the Classical streaming service, Idagio makes it easy to compare samples of different sets and zero in on the sets that deserve more attention.

The recordings I recommended in the first part of the article are still viewed highly by many critics as I write this. When a new recording comes out, it will get lots of good reviews, but over time, most tend to disappear from being recommended. The next new recording replaces them. Recordings still mentioned as key performances in later reviews have stood the test of time, in the case of the first part of this article at least 33 years.

After much thought, I picked one Nielsen box for Secrets of Home Theater and HiFi readers. I put more emphasis on sound quality than I would for other audiences.

The orchestra’s ability to play these works is more important than sound quality. Nielsen is hard to play, in part because of his scorewriting. Almost all the boxes are with 2nd tier or worse orchestras.

The London Symphony is one of the world’s great orchestras, but the Ole Schmidt box (see Vol. 1) shows surprisingly small execution issues. Recording conditions were dreadful, with power outages and a freezing hall, and all the symphonies were recorded in a short period of time.

Under music director Herbert Blomstedt, the San Francisco Symphony box set, discussed below, shows the San Francisco Symphony gets close to the accuracy of the world’s best orchestras, but the early digital sound is problematic.

The Chicago Symphony has no trouble playing the difficult passages, as can be heard in the recordings the CSO did of symphonies No. 2 and No. 4.

If you listen to only one Nielsen stream, it must be Morton Gould’s CSO performance of Symphony No. 2. He feels the energy this symphony needs, and the Chicago Symphony plays Gould’s fast tempos with margin to go faster cleanly. We know what to expect from the sound of an RCA recording of the CSO. Search for the 2016 remaster as part of a 6-CD set of all the Gould / CSO recordings. I discussed this CD set at the bottom of this music review article.

This Nielsen recording is likely the last of the great RCA/CSO recordings made just before the (acoustically disastrous) June 1966 hall renovations.

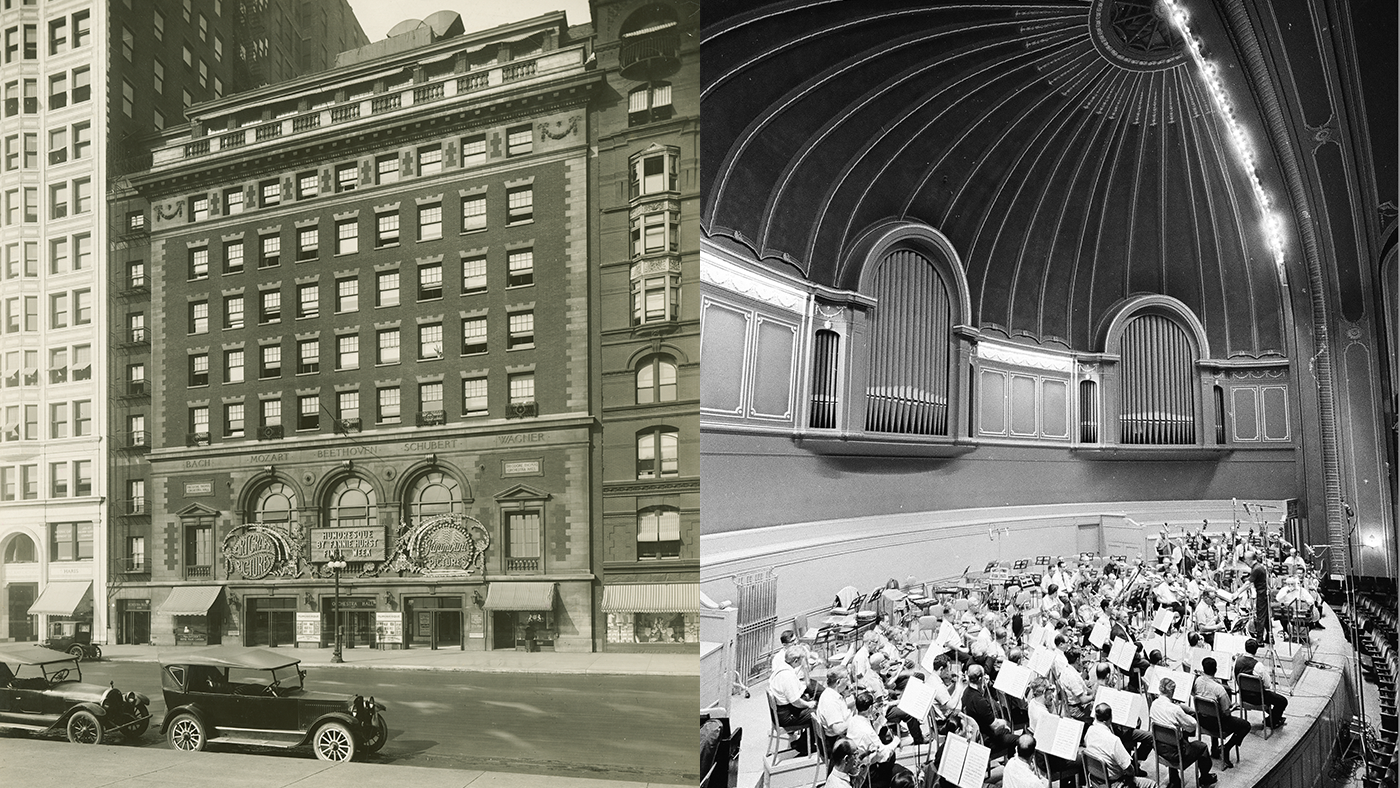

The outstanding performance of Symphony No. 4 conducted by then-music director Jean Martinon was likely completed after the CSO hall renovation since it was done in October 1966. The Martinon Nielsen recordings were the last RCA did in the hall. RCA, so dissatisfied with the renovated hall sound, moved to the Medinah Temple for recordings after 1966. The 4th symphony does not sound as good, listening to the 2015 remaster, but, it is not degraded to the point that I would have expected the move to Medinah Temple. The engineer and producer stay the same between recording the 2nd and 4th symphonies.

Just by luck, an article on the hall showed a photo of the stage of the Chicago Symphony Orchestra in June 1966 during the recording session of the first RCA Nielsen LP. This photo is of the clarinet concerto session with Benny Goodman.

https://interactive.wttw.com/playlist/2022/11/04/orchestra-hall-history

Note the small number of microphones.

From this photo, I cannot tell if it shows if any renovations to the hall have occurred yet.

Frank Villella, The CSO Archives Director, sent me a 20-page document that discussed all the changes made to the hall over 1966. Unfortunately, the document did not have a timeline for the date the acoustically harmful part of the changes were made.

The hall was used during the 1966 concert season, so I expect renovations inside the hall were done over the summer of 1966 but, I have no documentation to support this.

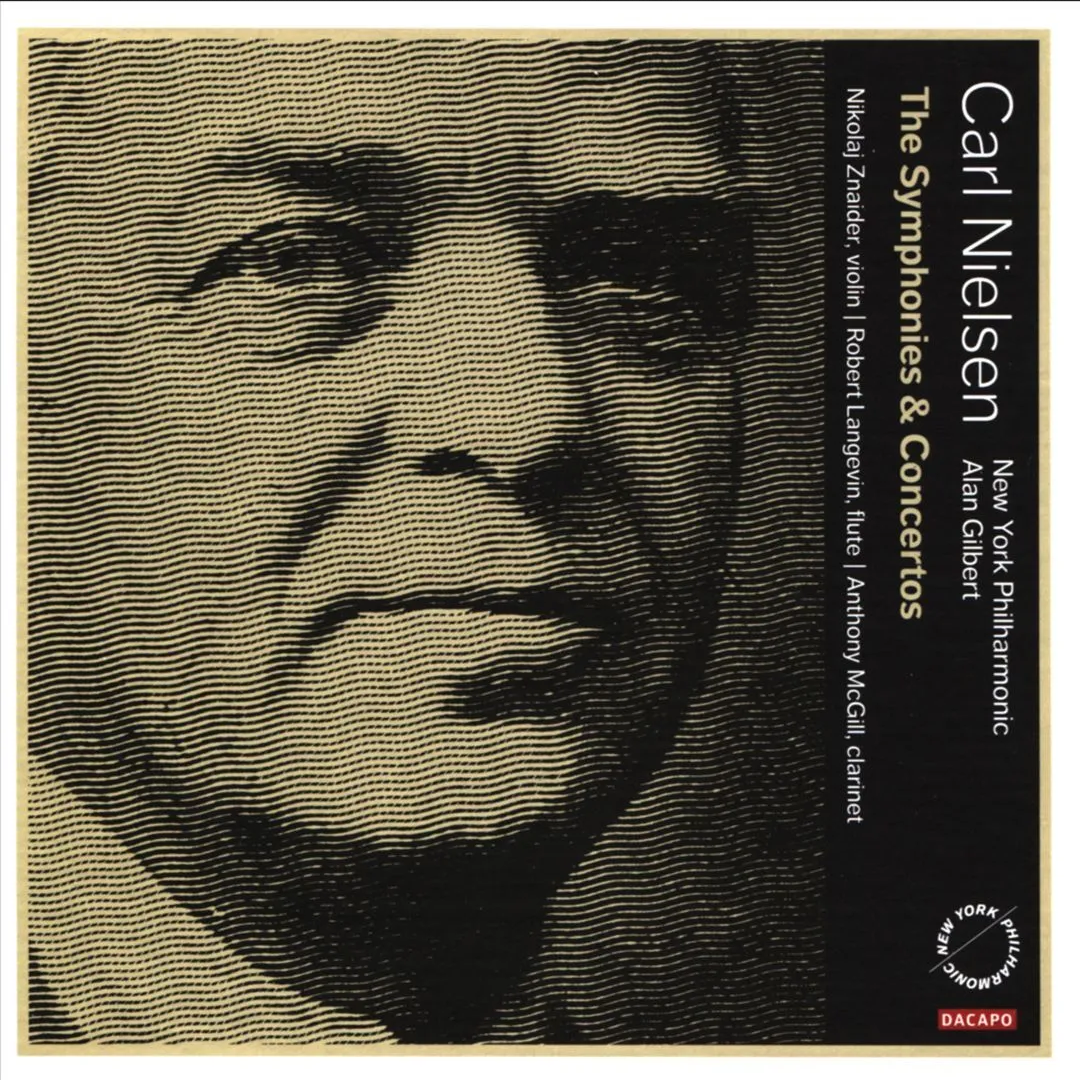

Nielsen: The Symphonies & Concertos New York Philharmonic conducted by Alan Gilbert on the Dacapo label.

Downloads are sold in CD quality, but this recording can be streamed in high resolution on Qobuz. The original SACDs are discontinued. The three individual SACDs of the symphonies are plentiful and cheap on Discogs. The complete box set is rare, pricy, and gets you nothing more. Dave Billinge of the Musical Web finds “The right and center channels are reversed” in the disc with symphony No. 5 and No. 6. I do not have them to verify if it is a single SACD or all three.

For the 150th anniversary, the Danish label Dacapo, with the Carl Nielsen and Anne Marie Carl- Nielsen Foundation, decided they needed to do something outside Denmark to jump-start Nielsen. In 2000, the Nielsen Foundation did a set of symphonies on CDs with Dacapo and DVDs with Unitel, with the Danish National Symphony Orchestra that got little notice.

The idea, this time, was to do a cycle with one of the world’s great orchestras. They picked the New York Philharmonic, which was not a stranger to Nielsen on LP or live.

The New York Philharmonic Archives make it clear why it had to be this orchestra. The archives are so advanced that a search on Nielsen finds every set of subscription performances they gave, including the programs given out at the concerts. They played 31 subscription sets (3 or 4 concerts each) from 1962 with the groundbreaking Nielsen 5th under Bernstein to 2022, with the 95-year-old Herbert Blomstedt conducting the 4th symphony.

Called the Nielsen Project, this was a serious attempt to raise his profile in the US, playing not just the symphonies but all the concertos and a couple of smaller pieces. The performances ran for five years, from Feb 2011 to Jan 2015, giving Nielsen a good long time to make friends with NYC music fans and letting the orchestra get used to playing the music outside symphonies 4 and 5, which were played close enough to these sessions that many in the orchestra already played them. Closing in on the birthday year, the NY Phil played an all-Nielson concert in October 2014 and the Clarinet concerto in January 2015, the 150th anniversary year.

To get the word out, the Nielsen Project would get national exposure. The New York Philharmonic This Week is a national radio series program that runs for the entire year. The program had Nielson on ten broadcasts, some from live recordings and some from the CDs, running from June 2012 to August 2015.

I am indebted to WFMT’s music director, Oliver Camacho, for compiling information on the broadcasts for me. Estlin Usher of WFMT was also helpful. By some miracle, the last of these broadcasts was repeated in August of this year, but I missed it. I was fortunate that Meredith Self, a librarian at the New York Philharmonic Archives, got me a copy. I could hear that they promoted the recordings, but no interviews occurred. Perhaps that was done in the earlier broadcasts. The Philharmonic produced a couple of short YouTube videos of Gilbert discussing Nielsen, and the Nielsen Project had a special website, which is now gone.

The NY Times covered almost every concert and was very positive about the Nielson performances. The CDs also got coverage. The Wall Street Journal joined in on the praise. What the Carl Nielsen and Anne Marie Carl-Nielsen Foundation was hoping for was happening by the decision to come to New York for the 150th-anniversary box.

Alan Gilbert was the incoming music director, for which hopes ran high. He was leaving the music directorship of the Royal Swedish Orchestra after eight years and was expected to conduct Nielson. Swedish orchestras have a strong tradition of playing Nielsen with the composer directly and later Tor Mann, who trained under Nielsen.

Gilbert says he was first turned on to Nielsen by a Blomstedt performance of the 4th Symphony in 1994 by the NY Phil. Then Dacapo’s plan hit a speed bump, as explained in an interview with Alan Gilbert on the project:

“I don’t listen to recordings really, actually… the producer “gave me some recordings – old Danish recordings – of interpretations that he says, “That’s really the true Nielsen spirit, you should go listen to that, “… and I didn’t… I try to look at the score. “So, I guess any blame or credit is squarely on my shoulders! ”

Gilbert said he would repeat Nielsen after the project was finished in 2015, but he left the New York Philharmonic in 2017. He is still doing Nielsen. In 2023, he did the 3rd symphony in Cleveland and the 5th in Tokyo.

The sound quality

Special recording sessions were not done to save money. Instead, the recordings were made live over several subscription concerts. Recording multiple performances allows editing and removal of audience noise by switching between takes.

Dacapo had the orchestra, but Avery Fisher Hall was a dreadful place to listen or record. The hall was completely rebuilt during the Covid shutdown. Lawrence Rock, Audio Director for the NY Phil, who has produced hundreds of radio broadcasts, gave advice on how to approach a task only the most fearless would attempt.

The only way to get a decent sound in a bad hall is to drop many microphones over the players. Using direct sound removes the aberrant properties of the hall. Some more distant mics were positioned to capture some hall sound. The booklet, which comes with this set, specifies a Decca Tree with outriggers using five DPA 4006TL microphones and two surround microphones were DPA 4015TL. The booklet also says the Danish DAD AX32 32-channel ADC recording system was used at the sessions. It converted at 384K samples/sec at 32-bit depth (DXD). With that many channels, you can use 32 mics directly to the ADC box. With its vast dynamic range, the microphones cannot overload it if the levels are correctly set.

Later, the producers and engineers worked to get the best sound possible at the mix sessions. They started with the sound from the more distant mics and then picked which close microphones to use and at what level and EQ. Some close mics were not used at all. With 32 tracks, it is easy to put up more than is needed.

What is missing from the microphones, because of hall issues, is created by electronics. The key to good results is that once the console controls are set, they are not touched except if the conductor asks for a balance change in a passage he thinks has not been captured correctly.

The 2nd symphony was the first recorded, and the engineers could not get Avery Fisher Hall tamed (Feb 2011). They also worked with older equipment limited to 16 channels at 96k sampling rates.

Symphony No. 3 is transitional in sound for this set. The engineers had little more than a year (June 2012) after the recording of No. 2, with the much-improved recording equipment and some experience in the hall. It’s better sound, but the excellent sound would have to wait.

The engineers would have another session for the violin and flute concerto a little later in October 2012, allowing more refinements in recording technique. The engineers had two more years to think about what to change before the final four symphonies were recorded in March and October 2014, when they hit pay dirt. The sound of symphonies No. 1 and No. 4-6 in this box, done in 2014, are as good as it gets for Nielson outside the 1965 2nd symphony with the Chicago Symphony engineered by RCA.

Critical assessment of the recording,

The reader can skip the next section, which gives details on how Gilbert performs each symphony.

——————————

Since I am recommending this box to you, I will take some space to quote from David Fanning, one of the leading musicologists on Nielsen in our time. The quotes are from firewalled Gramophone magazine reviews. I also quote Jack Larson, the author of the only English biography on Nielsen and writer for the free Musicweb international site.

This represents a tiny fraction of the reviews the box received in print and online, but Fanning and Larson have the CVs to back up the words.

Not with the CVs of Fanning and Larson, I added some quotes from reviews by David Hurwitz. He was at the performances. He is the executive editor at the firewalled website Classicstoday.

The first symphony under Gilbert

Fanning writes, “engagingly direct from the weighty yet lithe opening to the blazing conclusion and which is also sensitive to the moments of wonder along the way. Not quite a version to displace the classic San Francisco/Blomstedt on Decca, perhaps, but certainly one I’d be happy to return to.”

The second symphony under Gilbert

This was the first recording in 2011. Gilbert does not appear to be fully at home with Nielsen yet.

Larson writes of the Gilbert “Perhaps in Symphony No. 2, while enjoying the highest musical standards, one misses that absurd and exaggerated programme, the portraits of four extreme facets of human personality.”

Fanning writes (Gilbert) “does occasionally spoil it with sugary treats. He takes almost every espressivo and tranquillo as an invitation to luxuriate, and the result is a near-fatal loss of momentum in many of the lyrical passages”.

I have already pointed the reader to the Morton Gould / CSO recording. Fanning recommends the Schmidt London Symphony performance.

The third symphony under Gilbert

As noted above, the sound of this symphony is an improvement of No. 2 but does not approach the sound of No. 1 or the last three symphonies.

Larson writes, “This Symphony No. 3 is simply the most authoritative, penetrating, and fresh recording available today.”

Fanning writes the “entire first movement of the Espansiva is a conspicuous success and the two vocal soloists in the slow movement are golden-toned … the lurch forward at 9’10” in the finale rather confirms that Gilbert doesn’t always sense the broader flow.”

This assessment is very accurate, but only the last minute is a letdown. Fanning points to the Blomstedt San Francisco performance. Secrets readers will be happier staying with the better sound of the Gilbert.

The fourth symphony under Gilbert

Hurwitz writes this “features some really impressive energy and power … My only quibble with Gilbert’s interpretation concerns the symphony’s coda where Gilbert broadens the pace in the closing bars when Nielsen clearly wants to drive the music home.

Fanning writes (Gilbert) is absolutely determined not to interrupt the all-important flow. (The) Poco adagio (3rd movement) is superbly eloquent … (the) later stages of the finale are more jet-propelled than I think I’ve ever heard. Fanning is with Hurwitz on the ending of the 4th movement: “Far from observing the notated accelerando into the finale coda (which really would have been amazing), Gilbert slams on the brakes and takes the easy diversion into grandiloquence.”

Ole Schmidt knows exactly how Nielson wanted the final to go in his excellent reading of the score, but Fanning has problems with the London Symphonies playing.

Fanning would point to Blomstedt’s San Francisco performance. Strangely, he does this since Blomstedt does not follow the score at the end of the final in a different way, which is still not what Nielsen wanted.

The Coda of the last movement is an issue, but from the totality of the words above, it is a blemish on an otherwise excellent performance in far better sound.

The fifth symphony under Gilbert

Larson writes “There are too many new insights to make a list and it is enough to say that —you will be missing a glimpse of heaven by failing to purchase.”

Fanning writes of the 1st movement “Through the various phases of anguish, self-assertion and earth-shattering conflict, he and his players never lose the dramatic thread…In the 2nd movement, “Gilbert is a notch or two under the metronome mark for the Allegro (and the) following fugato, is not scary as it should be.”

Fanning wrote a whole book (1997) on the 5th Symphony pointing to the 1962 Bernstein recording. The 2017 remaster improved the bad sound, but not by much. In 1997, Fanning recommended the “extremely well-played “Blomstedt / San Francisco Symphony performance to gain better sound at the cost of some of “Bernstein’s special intensity.”

As an aside, Bernstein did No. 2 and No. 4 with the NY Philharmonic. Symphony No. 4, recorded in 1971, was very slow, and the reviews were not good. Many would argue Gilbert’s 4th is better.

The sixth symphony under Gilbert

Larson writes, “Here is Nielsen’s Sixth as you or I have never seen her before. It makes relevant Nielsen’s infamous and inglorious collision with Bartok. What a great achievement. It crowns his Nielsen symphony cycle by untangling a great paradox”.

Fanning writes “The variations finale feels too sane for its carnivalesque craziness to have maximum impact.”

—————————————-

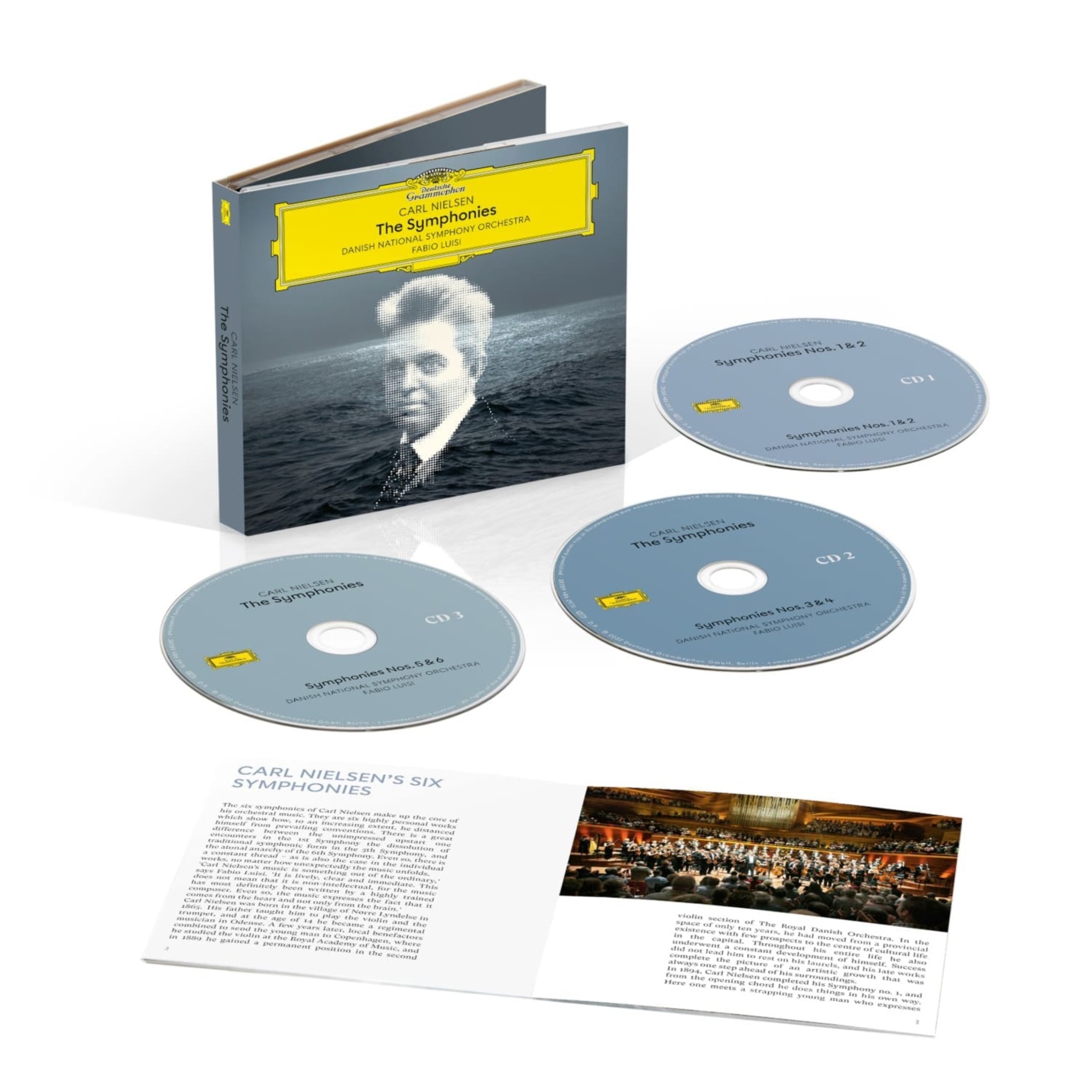

Nielsen Symphonies Nos 1-6 Danish National Symphony Orchestra conducted by Fabio Luisi Deutsche Gramophone Catalogue No: 4863471 for physical CDs. 96k High-Res download. Release Date: April 21, 2023

The Danish National Symphony Orchestra (DNSO) performs not under a Dane but the Italian Fabio Luisi, the music director since 2017, on the podium. New to Nielson, when he first worked with the DNSO before he became music director, Luisi appears to have come to love him. Recently, he has performed Nielson as a guest with other orchestras.

Like the Alan Gilbert set, this was sponsored by the Carl Nielsen and Anne Marie Carl-Nielsen Foundation. After the CDs, they gave a 6-concert performance of almost all the orchestral music he wrote. The live performances can be seen on the paywalled DGG Stage+ video streaming service, along with an hour-long video biography. In today’s market, these concerts stand little chance of making it to DVD or Blu-Ray.

The Carl Nielsen and Anne Marie Carl-Nielsen Foundation partnered with Deutsche Gramophone instead of the small Danish label Dacapo for the CD release. This time, they hit the mother lode. The 4th and 5th symphonies achieved the most prestigious award in classical music, Gramophone Record of the Year.

Unfortunately, DGG throws a wrench into the whole thing. Engineering is close-miked, and with ADCs now capable of up to 64 channels of conversion, DGG placed a microphone at almost every player. The engineers proceeded to the mix, post-live recording session, moving dials at the console like a Decca Phase 4 recording. But it is not just me:

“Unfortunately, DG appears to have reverted to its old Karajan-era habit of tampering with balances and spotlighting where it wants to. The result is a general swirl of confusing sound,” writes Steven Kruger of Fanfare Magazine in his review of the 4th and 5th symphonies.

In his review of symphonies No. 1 and No. 3, he writes, “But I noted at the time a reverberant blur in the recorded sound and detected signs of the engineer’s knob-twiddling in the way timpani support seemed to come and go”

In the Colin Anderson review in colinscolumn.com, he writes, “a ‘loud’ transfer that coarsens fortissimos in a rather reverberant acoustic.”

David Hurwitz did a YouTube review of this, calling it Luisi’s Very Loud Nielsen Cycle. The written reviews still need to be put up on his ClassicsToday website. Hurwitz blames Luisi for not balancing the orchestra, but it is the engineers.

It’s the worst example of knob twiddling since the bad old days of the 1970s when multitrack recorders fell into the hands of classical producers. The DGG engineers had only eight tracks of analog tape in the 1970s. In 2023, they could push the mics real close to the instruments and not worry, with 32-bit dynamic range, not available with those giant multitrack analog recorders.

Nielsen’s score is desecrated by the producer and engineers.

It is sound for Sonos speakers streamed in Bluetooth from a cell phone.

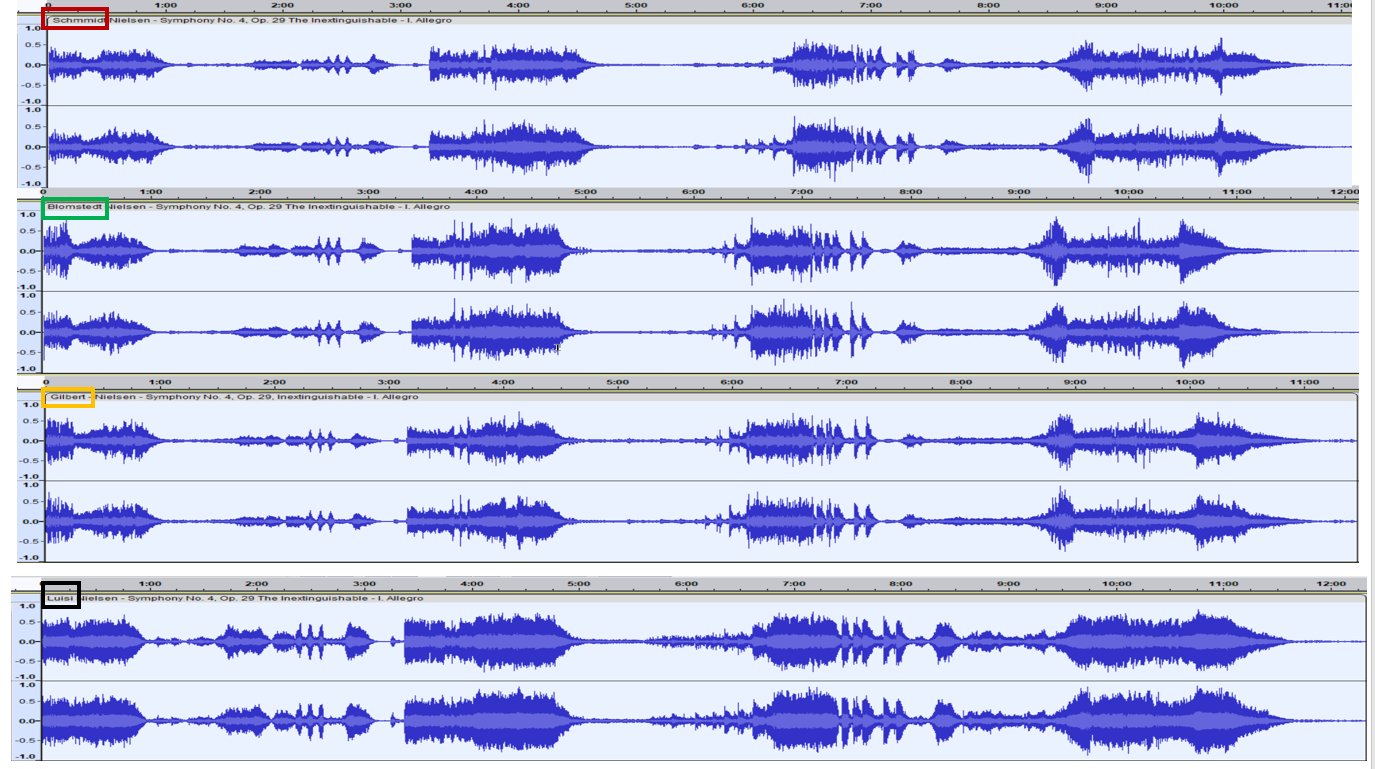

You want proof, I have proof. Shown are time domain plots, using Audacity, of the first movement of the 4th symphony from the 1974 analog Ole Schmidt, 1988 early digital Herbert Blomstedt, the 2014 Alan Gilbert, and the Fabio Luisi. The massive compression and highlighting are evident in this set of screen scrapes.

Each conductor plays the 1st movement at slightly different speeds. I aligned it so some plots are slightly time-compressed. You can see that some conductors spend more or less time on different sections of the movement.

Note that the time domain of the Luisi performance shows the soft parts are increased in level. The louder parts are mainly on the same level. The granular amplitude changes are missing in the Lusi, which can easily be seen in the other time domain graphs during the louder sections. The limitation in dynamic contrast is most dramatically seen at the final climax about 10 minutes in.

More proof is the DGG Stage+ live videos. Microphones are over every instrument except the brass and percussion, where they are a foot away. I wish I could show screen scrapes, but copyright law prevents this.

Time domain comparisons of the audio on the DGG Stage+ live video produce very similar results to the CDs. The audio team for the video has overlapping members with the DGG CD set, so I expect what I see on the video is the same setup used for the CDs.

Given the overwhelmingly positive reviews, I will not put my foot in my mouth discussing the performances. Norman Lebrecht gives an excellent summary:

“The Italian Fabio Luisi has two advantages over his predecessors on record. He is principal conductor of the Danish National Symphony Orchestra, which speaks Nielsen as its mother tongue, and, he brings the skills of an opera interpreter, balancing flare-ups of passion with overall structure.”

We have a vast set of archival performances from the 1930s to 1950s of Danish Radio Symphony performances with conductors who played under Nielsen. Schmidt and Blomstedt, a generation later, trained by these musicians, give us what Nielsen wanted in listenable sound.

Luisi changes what the composer wanted. I still find the box’s appearance to be something to welcome with open arms, as DGG is doing its job as the largest classical label to promote these recordings.

This is not a set for those of us who found Nielsen, as in my case, in the 1970s, promoted by my high school teachers who found him in the 1960s. We raved, but Nielsen is still as unknown today as when we discovered him.

The Luisi interpretations are different, as Lebrecht so insightfully captures, but perhaps they are the ones that will show a much larger audience that Nielson IS one of the great symphonists. Luisi’s work may make the case that the symphonies should be in the canon of classical music. This is for Gen X to Gen Z and beyond and mixed for what they listen on. The set brings the flicker of hope that Nielsen will finally be understood to be the giant of a composer that he is.

A deeper look at the Symphony No. 6

The 6th symphony is totally different from the other Nielsen symphonies. More academic papers and book chapters have been written about this symphony, and the rate of publication is increasing with time. In the DGG Stage + biography, Herbert Blomstedt says that No. 6 is “in many ways his greatest symphony.”

Unification is the key to a performance of the 6th. Thomas Dausgaard, a Danish conductor a little more than one generation after Schmidt, then music director of the DNSO, is the best for me. He takes his cue from the slithering Bartok night music in the third movement and one-fourth movement variation. He then starts twisting other sections so they, too, slither around.

The problem is it is on YouTube. It is a very good-sounding YouTube, but few of my readers will be interested.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5nUKn5rUCG8

I was desperate to find any commercial recording that matched Dausgaard for unification. I found it with Sakari Oramo and the Royal Stockholm Philharmonic Orchestra on BIS. If Dausgaard slithers for unification, Oramo slashes. It is really over the top, but it is my favorite on CD. The last of the recordings of the otherwise, to me, undistinguished Oramo box is the only one with excellent sound.

Hurwitz writes, “The performance has a rare unity and integrity.”

Most critics point to performances that are less menacing but less unified to me.

Stephen Johnson surveys over ten recordings of Nielsen’s Symphony No. 6 on a BBC3 program Discovering Music. He picked the Blomstedt San Francisco Symphony performance for first place, and Oramo got second place. This educational audio makes a great introduction to the Sixth Symphony.

https://www.bbc.co.uk/sounds/play/p03ckq0t

Other critics often cite the Ole Schmidt LSO performance as the finest. The 6th Symphony leaves so many interpretive questions so widely different performances can all sound valid. If one is to find his own answer to what this symphony is about, it requires listening to multiple performances.

Herbert Blomstedt 2nd Nielsen Cycle revisited.

I underrated this box set in part 1, as you can tell from how often it was mentioned above. The set is 33 years old but still comes up as the best performance, with different symphonies for different critics. The photo I show is of a 2014 reissue with slightly better sound. You must hunt for this box when you stream. What first comes up is from the original CDs.

That this is the only box that a conductor got to do twice may be part of what makes the performances so good. Blomstedt’s training in Sweden was in part done by music teachers and then conservatory professors, who were one generation from Nielsen. Nielsen spent a significant amount of time in Sweden, which, in some parts of his life, was more welcoming than Denmark.

The only box set to be as sighted as often in modern reviews is the Danish Ole Schmidt’s LSO box from 49 years ago (1974). Born a year apart, Schmidt (July 14, 1928) and Blomstedt (July 11, 1927) overlapped with Nielsen, who died on October 3, 1931. Schmidt trained in Denmark in the music conservatory Nielsen had headed at the end of his life. Schmidt’s musical training from the start would have been with those who had seen Nielsen perform and were perhaps in an orchestra he conducted.

At age 96, Blomstedt is still conducting Nielsen. Not to be missed is a blazing 2015 performance of No. 5 done with the score closed on the music stand.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=w4RLtP9iSMU

The problem with the Blomstedt box is the early digital sound of the recordings made from 1987 to 1990. The 5th is the first recording Decca made in San Francisco with the then-new music director. Even if it had been analog, it would have problems. As the Decca engineers went along, they got a better sense of how to record in the hall, so the sound improved. Digital equipment was also evolving.

The collector’s edition sounds better, but you can do only so much if all you have is a two-track digital recording master – apply some EQ and add electronically generated hall acoustics.

A big surprise

Nielsen Symphony No. 4 performed by The Royal Danish Academy of Music Orchestra.

This is in a 150th-anniversary box of The Royal Danish Academy of Music. This recording, the only Nielsen symphony in this 12 CD box, shows the Royal Danish Academy of Music prizes it. It streams and is available for download alone from the box.

The Royal Danish Academy of Music Orchestra is an all-student orchestra of the music conservatory. You would have never guessed if I had not told you the orchestra is all student- based. They must have spent an enormous time rehearsing. The students are discovering why they became musicians and play differently than the grizzled professionals. Here, they play their hearts out for Nielson. This recording shows Nielsen will speak to generations to come.

The kids got more enthusiastic than the engineers expected, resulting in some compression.

The Danish conductor, Michael Schønwandt, a generation after Schmidt, is on the podium. He has significantly deepened his interpretation from a 1999 CD he did of the 4th with the DNSO.

Conclusion

All my life, I have loved Nielsen and have been running around since, telling everybody else they must listen to him. Many others have done the same thing from 1963 with the first Bernstein stereo recording. It has not worked.

The flicker of hope is the operatic tradition of Italy, which Luisi was steeped in, bringing warmth to music from freezing Denmark. That many more people will learn to love Nielsen in the hands of Luisi. Fiona Maddocks of the Guardian writes:

“These performances … are thrilling enough to turn you into a Nielsen addict.”

For Secrets readers, the DGG sound will be a deal breaker. For you, I point to Gould with the CSO for Symphony No. 2 and the Gilbert box for the remaining symphonies. It is not just the recorded sound. As good as the DNSO plays Nielsen, the CSO, and NY Phil, on everybody’s list of the world’s top 10 orchestras, play it better.