When high fidelity audio products started to gain a foothold in the domestic market, towards the end of the Word War II, Britain and the US were trailblazers. While many of the manufacturers of that period no longer exist, some of the most successful that do are British.

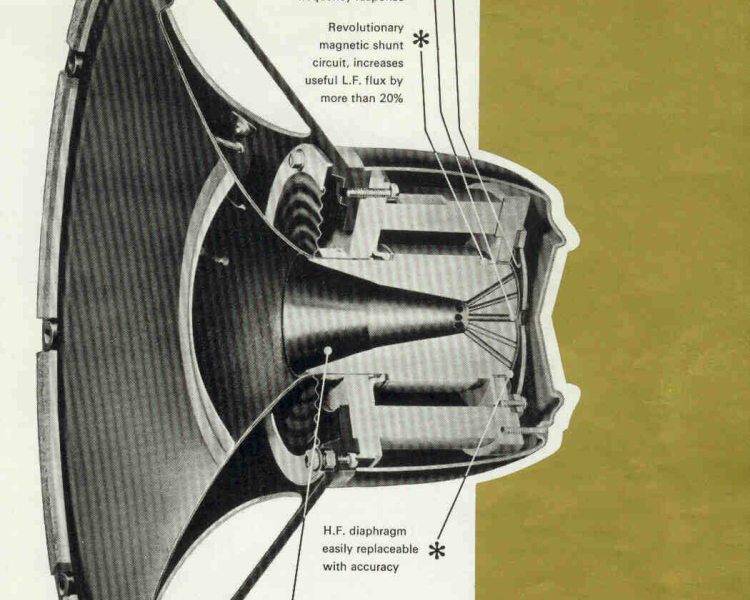

Tannoy, for example, was founded in London in 1926, as the Tulsemere Manufacturing Company. It trademarked the name Tannoy in 1932; an abbreviation of tantalum lead alloy, the material employed by TMC’s founder, Guy Fountain, to make the electrolytic rectifiers he used to charge batteries for early radio sets. Tannoy came to prominence during the War when it made public address systems supplied to the army. Before long, the public started calling PA systems ‘tannoys’, and the name stuck. In 1947 the company unveiled the Tannoy Monitor at the London Radio Show, with its Dual Concentric driver; the UK’s equivalent of the coaxial driver found in the Altec Lansing Duplex 604, then widely used in the US recording industry.

The driver’s relatively flat frequency response and lack of phase issues saw its adoption as a studio monitor throughout Europe. This Dual Concentric design is, of course, to this day a defining feature of Tannoy loudspeakers.

Secrets Sponsor

QUAD, founded in 1936, is another British brand with roots in wartime PA systems. The original company – S.P. Fidelity Sound Systems, renamed in 1936 to the Acoustical Manufacturing Co – entered the domestic market with the QUAD 1, a valve amplifier based on the company’s PA designs. The name QUAD is an acronym of Quality Unit Amplifier Domestic, the somewhat clunky title for the QUAD I. In 1953 QUAD manufactured the sequel; the aptly named, and legendary, class-A monophonic QUAD II valve amplifier, the reference amplifier of its day, having reduced harmonic distortion to levels unheard of at the time. Such was the success of the QUAD line of products that the Acoustical Manufacturing Co changed its name to QUAD Electroacoustics in 1983. By that time, QUAD had become equally well known for its ground-breaking transducers, including the 1957 QUAD ESL, the world’s first commercially produced electrostatic loudspeaker.

When stereophonic LPs became commercially available in the late 1950s and the BBC began broadcasting in stereo in 1958, it heralded what some consider to be the golden age of hi-fi. In the twenty years that followed, British hi-fi thrived and many of the manufacturers we know today were founded. KEF, an acronym of the Kent Engineering & Foundry site in South East England, where KEF was based (and, incidentally, near were this author grew up) was founded in 1961. KEF began manufacturing the BBC-designed LS5/1A monitors, precursor to the highly regarded LS3/5A studio monitor, which used KEF-made drivers. The BBC’s research department had invested considerable resources in reducing colouration from outside broadcast and studio speakers, leading a hi-fi magazine of the 1970s to later comment “The British Broadcasting Corporation is probably the single most influential body in shaping a public’s awareness and expectations of high fidelity sound”. The BBC designs were licensed out to a number of other prominent British manufacturers, including Spendor (a portmanteau of Spencer and Dorothy Hughes, names of the firm’s founders) and Rogers. The BBC designer of the LS3/5A, Dudley Harwood, eventually retired from the BBC, taking with him a patent for polypropylene-coned bass-midrange woofers, which he used to start the business he called Harbeth.

Secrets Sponsor

Five years after KEF was founded, Bowers & Wilkins appeared in Worthing, England, where John Bowers hand-assembled his speakers for local clients. By the mid-1970s the company had patented the use of Kevlar fibres in stiffening resin, producing the yellow drivers for which B&W speakers are now famed. Not long after this, NAD (New Acoustic Dimension) began trading in 1972, and in 1978 produced the NAD 3020; a sub-$135 solid-state integrated amplifier that surprised the hi-fi community with its audiophile performance at an unheard of entry-level price point. By the time NAD had released the 3020, the market for British integrated amps was already reasonably well-established. Amplification & Recording Cambridge – Arcam – had released its first commercial product two years earlier in 1976, the A60 integrated amp, with significant success.

Naim Audio, founded in Wiltshire, England, incorporated in 1973 and produced the NAP 200 power amplifier that year. In 1983 it followed the integrated amp successes of the 3020 and A60 with its NAIT, a popular – if controversial, due to its unconventional rejection of tone controls – integrated amplifier. In the same year Naim was founded so too was Rega, which introduced the Rega Planet in 1973, followed shortly thereafter by the first Rega Planar. The Planet and the Planer had a tough act to follow though. Shortly before the Planet’s release, Linn had released the legendary, market-dominating, Sondek LP12. Linn had been founded in Scotland, in 1973, by Ivor Tiefenbrun, to sell turntables made by his father’s company, based on Ivor’s design. The LP12 featured a patented, central single-point ball bearing that enabled smooth, continuous playback speed. This, together with the LP12’s unusually good acoustic isolation resulted in a turntable that set a new benchmark. It redefined the audiophile community’s understanding of what record players could achieve, and is widely regarded as one of the most significant milestones in the history of high fidelity audio.

As the 1970s grew to a close, turntables were set to face a battle for supremacy. Audiophiles would soon be introduced to the compact disc. Bob Stuart and Allen Boothroyd, who had founded Meridian Audio in 1977 – the first company to manufacture active speakers for the domestic market – nailed their colours firmly to digital’s mast. In 1985, they produced the Meridian MCD, the world’s first high-end CD player.

The 1950s-1980s were, undoubtedly, formative years for hi-fi as we know it, and British manufacturers were among those pushing back boundaries. However, with the legacy of the twentieth century behind it, increasing commercial uncertainty in Britain and growing competition from outside, can we rely on British manufacturers playing a central role in the hi-fi to come?

The British economy is in a state of uncertainty. The British public’s vote on June 23, 2016 to leave the European Union – so-called ‘Brexit’ – has negatively impacted British consumer confidence and the United Kingdom’s economic growth. Following the Brexit vote, the pound fell on foreign exchange markets, making imports more expensive for manufacturers that rely on buying foreign parts, and contributing to the UK’s highest rate of consumer price inflation since 2013. In response to this, on November 2, 2017 the Bank of England raised interest rates for the first time in a decade. The Bank of England does this when it wants to make borrowing more expensive, both for banks and consumers, who would end up paying higher interest rates on loans. This, the Bank hopes, will result in less spending in the economy and, if all goes to plan, reduce consumer price inflation.

How is this relevant to British hi-fi? Well, for a start, it means British consumers have less money to spend on ‘luxury’ items. The hangover from the financial crisis ten years ago is still being felt and consumer confidence has not returned to pre-crisis levels. Consumer confidence declined in the immediate aftermath of the Brexit vote and, while it has recovered to a degree, the current rate of price inflation in Britain, and the worst recorded wage growth since the 1860s, means increased confidence is not supported by increased disposable income. What is more, this economic uncertainty may continue for a while: the UK isn’t scheduled to leave the European Union until March 2019.

Alongside this uncertainty is the changing nature of Britain’s economy. Whereas once the industrial centre of the world, Britain now imports more than it exports. During the 1960s-1980s, when British hi-fi thrived, Britain exported more than it imported. The UK’s current trade deficit stands at £48 billion, which is entirely due to the UK importing £135 billion more in goods than it exported. In services, by contrast, the UK recorded a trade surplus of £92 billion in 2016.

Despite the relative decline of manufacturing as a share of the British economy, British manufacturing is still strong globally, with Britain ranking as the 8th largest manufacturer by output in the world. Moreover, the heritage of British hi-fi is such that it attracts investors from outside Britain. This is perhaps most clearly evidenced by the July 2017 acquisition of Arcam by Harman, bringing one of Britain’s leading hi-fi manufacturers under the same roof as several US companies. British hi-fi manufacturers are, in fact, increasingly owned by parent companies outside the UK. Naim is owned by the Vervent Audio Group (French); almost 50% of Meridian is owned by the Swiss Richemont Group and the U.S. film company New Regency; KEF has Chinese parentage; Tannoy is part of Music Group (headquartered in the Philippines); the list goes on. This outside ownership and the continuing prestige of British hi-fi manufacturers means they may yet weather the storm presented by Brexit and domestic market uncertainties.

In parallel with these economic conditions, the British hi-fi market, like those elsewhere, is in the midst of profound change with the rise of streaming. This is not, of course, necessarily a bad thing. Nick Simon, from market analysts GfK, points out that Britain’s separates hi-fi market grew slowly throughout 2016 and into the first part of 2017. Turntables are still staging a remarkable resurgence, with vinyl sales up 53% in 2016 on the previous year, and turntable sales up 62% by volume. Turntable sales have, however, grown slightly less by value (56%), indicating that some buyers are opting for lower-priced routes into vinyl; often basic all-in-one units rather than proper, grown-up turntables. Nonetheless, British consumers are clearly starting to look for something streaming does not offer, be that better quality audio or collectability. Brits are still, it seems, attracted by the tangible qualities offered by physical media; the ritualistic satisfaction of unsheathing a record from its sleeve, and sense of ownership it entails. As with audio consumption in the rest of the world, the growth in Britain of streaming – up 68% in 2016 on the year before – and of consumers listening to audio on their mobile phones, may seem anathema to audiophiles, but this trend exposes new consumers to the benefits of high fidelity, providing a positive outlook for those British manufacturers so central to the industry. As Naim’s Managing Director Paul Stephenson noted in an article in the British newspaper the Guardian, “Partly thanks to the likes of Apple, hi-fi is becoming part of people’s lives again … it’s now our opportunity to get into that.”

British manufacturers have played a seminal role in the development of high fidelity. Partly due to this, it’s arguable that British hi-fi’s best years are behind it; that we are less likely today than we were fifty years ago to see the emergence of new, pioneering British hi-fi manufacturers. Yet, on the other hand, it is clear that in Britain separates hi-fi is still an attractive proposition to consumers, that the homegrown manufacturers that make it are among the best and, more often than not, supported by the resources of international parent companies. The economic uncertainties in Britain might be set to continue, but British hi-fi manufacturers have a strong foundation – an almost unrivalled heritage – from which to embrace the future.

- BBC’s Home Service, Hi-Fi Answers, August 1979

- UK suffering ‘first lost decade since 1860s’ says Carney, Financial Times, December 5, 2016

- UK trade: a deficit in goods but a surplus in services, House of Commons Library, November 9, 2017

- Naim Audio rides wave of hi-fi fans searching for better sound, Guardian, March 6, 2015