The new TEAC W-1200 Cassette Tape Deck not only records and plays, but it can record two cassettes at the same time, and it will also dub (copy) one tape to another.

TEAC W-1200 Cassette Tape Deck Recorder/Player

- Easy to use

- Can copy from one tape to another blank tape

- Digital output for copying tape to your laptop

The resurgence of vinyl surprised everyone, and it continues to surprise everyone, that is, except for those of us who have bought new turntables and lots of vinyl recordings. We knew it was a good idea.

Behind the scenes, cassette tape recorders and players have also caught on . . . big time too.

Particularly the younger folks (Gen Z: Ages 12-27 in 2024) are having a grand time with them, but lots of others as well. Those who grew up in the 1970s through 1990s are digging their recorders out of the storage room and playing tapes that they still have. I bought one in the 1990s, but I can’t find it. We moved from Baltimore, MD in 1989, and it got lost (or stolen) somewhere. I remember how much fun they were. I had to open the cassette drawer, put a tape in, close the drawer, perhaps rewind the tape because I stopped the tape playing in the middle the last time I used it, press play, stop, fast forward, etc. There was constant touching of the recorder/player, and lots of interaction, not just listening to the music. Maybe that is what Gen Z really likes about them . . . the constant interaction.

Some newbies feel that reel-to-reel (RTR) tape recording is a hassle, but because they like the sound of analog tape, cassettes have been substituted. There are plenty of collectors too who see the value of having older recorders and commercial tapes. For garage bands, recording themselves on cassettes and sharing them with others is a great idea. And, perhaps most importantly, cassette players are portable.

A Short History of Audio Cassettes

Before (mostly) our Time

1935: Reel-to-reel (RTR) recording was invented and used by professional recording studios and radio stations. Many of the later ones have been taken out of the back rooms, restored, and sold on E-bay.

1958: RCA introduced the first reversible cassette tape, although the cassette was really big. It had 60 minutes of stereo quarter-inch reel-to-reel tape within a plastic cartridge. Not exactly portable.

The Rise (and no, not Batman) of the Compact Cassette

1962: Philips invented the first compact cassettes for audio storage. This format became the standard due to Philips licensing the technology to other companies for free.

1963: The Compact Cassette was released by Philips, initially marketed as an inexpensive music recorder/player.

1964: The first home compact cassette recorders were released in the United States.

1965: Dolby Noise Reduction was released.

1966: 8-track tape players were introduced for cars.

1968: TEAC introduced the first stereo cassette tape recorder A-20, made in Japan.

1970: Chrome cassette tapes were sold by BASF. This gave a better frequency response with higher bias voltage.

The Growth of Cassette Tape Deck Popularity

1968: Cassette players became available for cars and became mainstream by about 1975.

1979: Sony released the Walkman, a portable music player for those on the go.

1980s: Cassettes surpassed LPs in sales.

What Goes Up Must Come Down

2001: CDs sounded better than cassettes and started replacing them in popularity, especially since portable CD players were available. The concept of music being “digital” undoubtedly was also a factor.

2009: The last major label release on cassette was “The Last Kiss” by Jadakiss.

CLASSIFICATION:

Cassette Tape Recorder and Player (non-portable)

NUMBER OF RECORDER/PLAYER CASSETTE SLOTS:

2 (parallel recording capability)

TRACKING:

4-Track, 2-channel stereo

TAPE HEADS:

1 record and play head for each tape slot

TAPE SPEED:

4.8 cm/sec (1-7/8″/sec)

PITCH CONTROL:

± 12% (for playback only)

REWIND TIME:

120 seconds for C-60 tape

WOW & FLUTTER:

0.25%

FREQUENCY RESPONSE:

Type I Tape – 30 Hz – 13 kHz ± 4 dB

Type II Tape – 30 Hz – 15 kHz ± 4 dB

S/N RATIO:

59 dB, A-weighted, at 0 dB VU recording level

AUDIO INPUTS:

1 pair RCA, 1 mono microphone (mic-mixing capability for Karaoke)

AUDIO OUTPUTS:

1 pair RCA

INPUT IMPEDANCE:

33 kOhms

OUTPUT LEVEL:

0.46 Volts

HEADPHONE OUTPUT:

1/4″ phone jack, 15 mW at 32 Ohms headphone impedance

USB DIGITAL OUTPUT:

USB-B

USB DIGITAL OUTPUT FORMATS:

8/11.025/16/22.05/32/44.1/48 kHz 8/16 bit

DIMENSIONS:

17.1″(W) × 5.7″(H) × 11.3″(D)

435(W) × 145(H) × 285.8(D)mm

WEIGHT:

9.3 Pounds

MSRP:

$499.99 USD

Website:

Company:

SECRETS Tags:

TEAC, W-1200, Cassette, Tape, Deck, Recorder, Player, Reel-to-Reel

Secrets Sponsor

The TEAC W-1200 is an “at home” recorder/player. It is not meant to be portable. However, there are portable players out there.

The most notable feature is the fact that it has two cassette slots (trays) so that you can record two cassettes at the same time, but as is more likely, you can dub (copy) a cassette. So, if you and your friends have cassette players, and you purchase some one-of-a-kind old commercially recorded cassettes, you can share them among yourselves.

The W-1200 is available in black (shown at the top of this page), and silver, shown below. They are high-res photos, so you can click on them and enlarge them to see all the features – and there are lots of features.

From left to right are the first cassette slot, on/off switch, and Pitch (speed) Control Dial (± 12%). This is for when a cassette that was recorded somewhere else and the speed is a bit too fast or too slow, you can adjust it, but only during playback.

Next are the LED panel (counter, recording level), Return to 0 (on the counter), Dimmer, Repeat, Parallel Recording, Dub Start, and the Return to 0 button for the cassette slot on the right.

Below the panel are the rewind, fast-forward, stop, and play buttons for both cassette slots. Then the recording level dial, eject, and microphone socket (mono only) and microphone recording volume level control. On the right are headphones socket and volume control, and cassette slot 2 eject button. On the far right is a timer and noise reduction switch (only operates in playback).

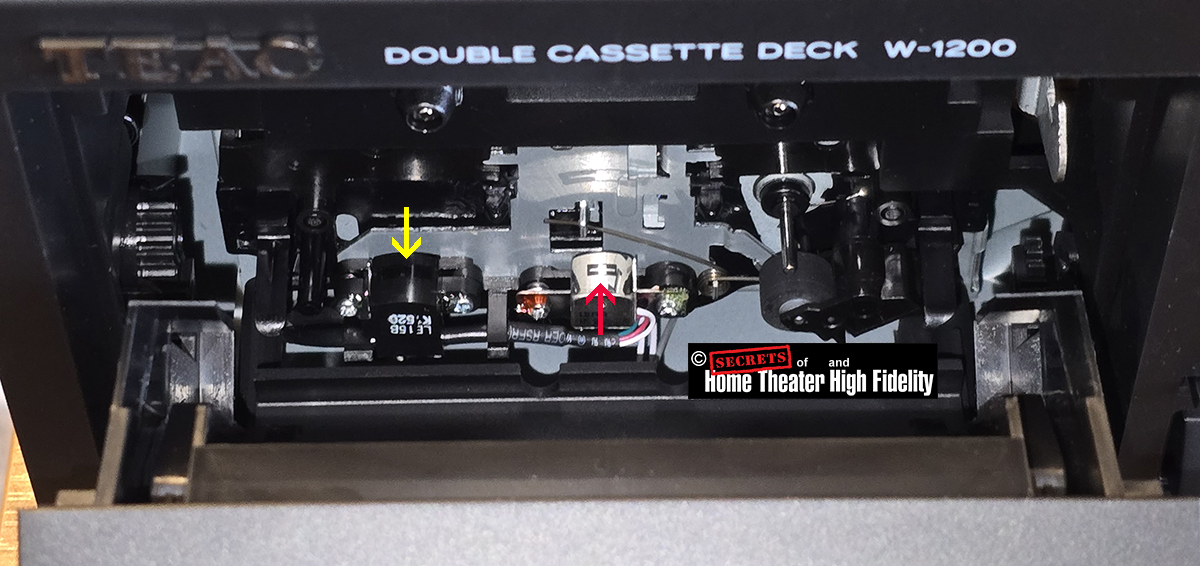

Inside the cassette slot (tray), shown below, you can see the erase head (yellow arrow) and record head (red arrow). Some recorders have a separate record head and playback head. This would let you monitor the sound coming off the tape while you are recording. But, it isn’t really necessary.

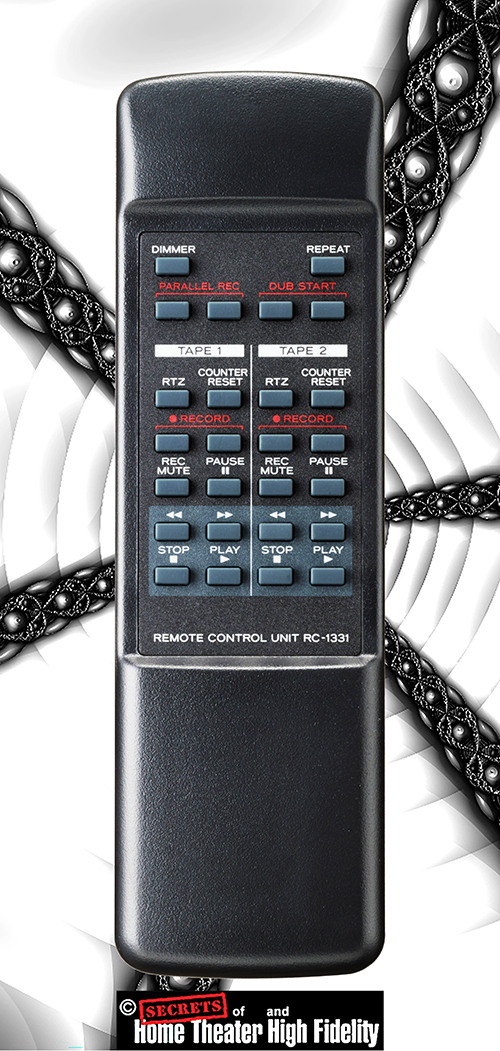

The remote control duplicates the essential functions on the front panel.

Cassette recorders and players have a tape speed of 1-7/8″ per second (4.8 cm/sec). The tape is only 1/8th inch wide and has 4 tracks. Reel-to-Reel (RTR) decks, by comparison, have tape speeds of 3-3/4″ per sec, 7-1/2″ per sec, 15″ per sec, and 30″ per sec. The tape is mostly 1/4″ wide, but studio decks can have tape that is 2″ wide and a lot of channels. Consumer RTR decks are usually 3-3/4″ and 7-1/2″ per sec, selectable with a switch.

The higher speed of RTR decks results in much higher fidelity than cassette decks, but cassettes have electronics to at least partially compensate. You can read a long treatise on RTR decks in the article I published a few years ago.

The irony is that the faster the tape speed, the more roll-off there is in the bass. High frequencies are better though.

If you have a cassette deck, you are sure to notice that the blank tapes are available in several varieties. Type I is also called Ferric, which means the recording coating on the tape is iron oxide (rust). Type II has chrome as the coating. There is also a back coating on the rear side of the tape. Both types of tape require a different “bias” voltage which consists of a high-frequency sine wave, usually about 60 kHz, that is mixed in with the recording signal. The bias voltage increases the magnetizing capabilities of the metal coating. During playback, a 60 kHz notch filter is used to remove the bias frequency. The tape box might also say 120 µsec (microseconds) for the Type I tape and 70 µsec for the Type II. This refers to the EQ that is applied for the frequency region (about 3 kHz and lower) to correct for a change in the roll-off that occurs due to the slow tape speed in cassette decks. Ferric vs. chrome tapes have a different frequency at which the EQ is applied.

Dolby Noise Reduction (DNR) was something that was added to RTR and also to cassette recorders. DNR reduced the tape hiss that is prominent at slower speeds. The W-1200 has Noise Reduction, but only for playback, to be used with the commercial cassette tapes from way back then (but are collectible now).

The DNR chipset is no longer available, so TEAC reverse-engineered the chip and created a compatible NR chipset for the W-1200. It works perfectly as a DNR chipset, but the term “DNR” would not be accurate.

On the rear panel, there are one pair of RCA analog input jacks, one pair of RCA analog output jacks, and one USB-B jack (connecting the W-1200 to your computer for creating a digital version of your analog cassette tape recording).

I played digital music files from my PC through analog outputs on my sound card. The outputs were connected to the analog RCA input jacks on the rear of the W-1200. RCA analog outputs from the W-1200 were connected to the inputs on the sound card.

To record, you just push the record button on the W-1200 front panel to set the recording volume, The tape is not moving at this point, and you can listen to the recording being played by using the headphone jack or the analog RCA jacks on the rear panel. So, at this point, the headphone and rear panel jacks serve as recording monitors. To actually record, you then press the play button.

Setting the recording level is very important. This is accomplished by pushing the record button, starting the music playing that you want to record, and adjusting the recording meters (by turning the record level dial) so that the average loud sounds hit just at 0 dB VU on the meter. Here is a photo. I adjusted only the left channel for the photo so you could easily see the horizontal recording level bar. Most of the sound is in the minus 6 to minus 20 dB VU range. There can be a few cymbal crashes or bass drum thud peaks that hit +3 to +6 dB VU. With VU meters, 0 dB VU is the average recording level at that point, not the peak. 0 dB VU is usually calibrated to be equivalent to minus -18 dBFS recording level in a studio digital recorder. This gives the studio 18 dB of headroom before clipping. By setting the analog tape recording level this way, you get the maximum dynamic range and the lowest background noise (tape hiss).

Copland, Louis Lane, Atlanta Symphony Orchestra, “Appalachian Spring Rodeo, Fanfare for the Common Man”

I recorded two of my most stressful music tracks. The first track is Copland’s Fanfare for the Common Man. This Telarc version is the most intense that I have ever heard. The heavy bass drum thuds cracked the + 6 dB VU spot. When I played the recording through a set of Sennheiser headphones, the drum thuds did not sound distorted. So, even a cassette recorder can capture extreme dynamics.

Anne Akiko Meyers, “Mirror In Mirror”

The second recording is Mirror in Mirror, with Anne Akiko Meyers on violin. The stress that this recording places upon recording and playback devices is that she goes to the highest notes that the violin can play. I did notice a bit of flutter in the background, very slight, and probably not noticeable for cassette fans. I measured 0.52% RMS Wow and Flutter. The spec is 0.25%. However, I do not have a calibration tape cassette that is lab grade with as low W&F that can be recorded on to really test this. The 0.52% is the W&F that the W-1200 recorded plus the W&F that the W-1200 also produced during playback.

I noticed that with regions of a music track that had complex content (lots of instruments), there was some congestion in the sound.

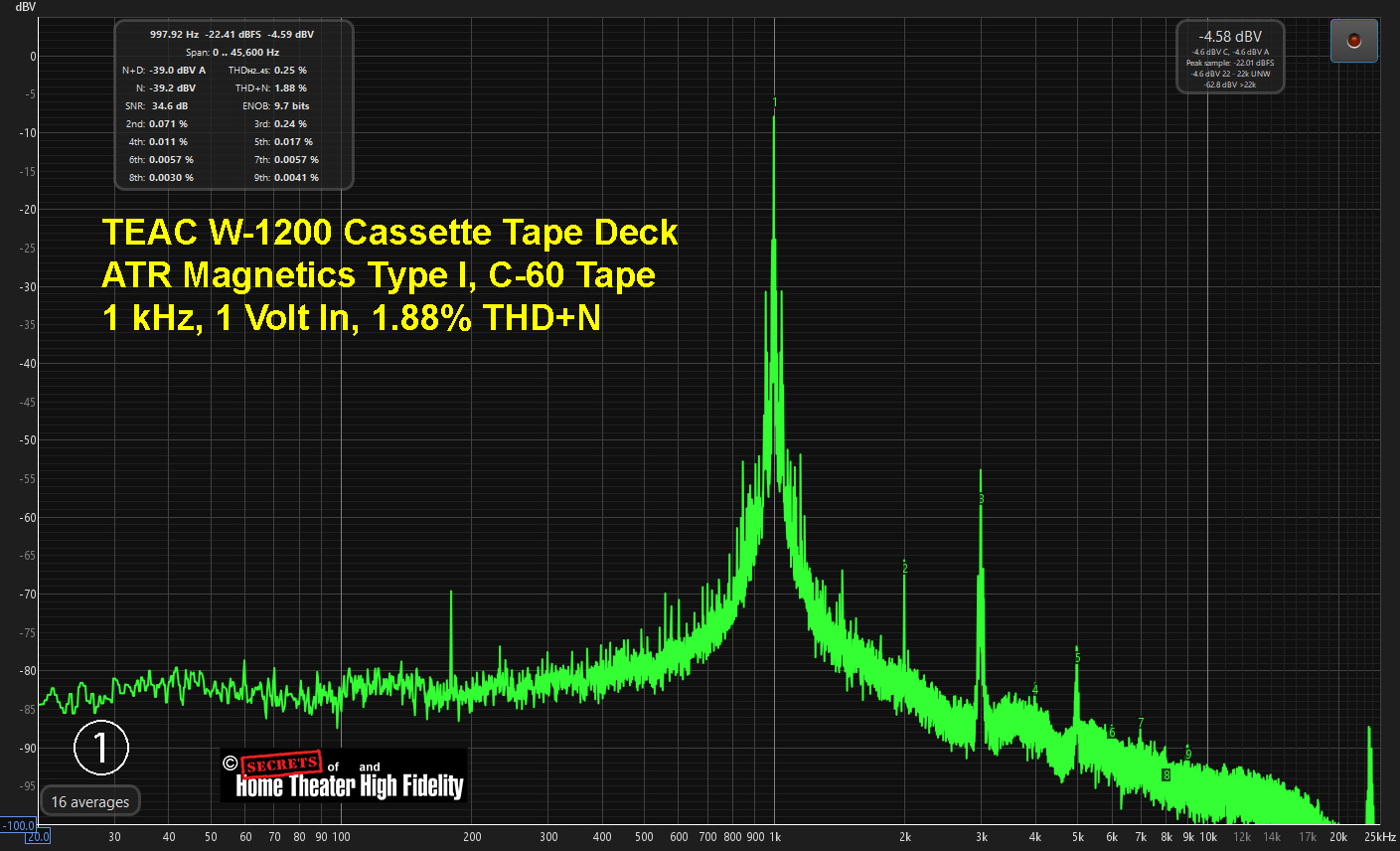

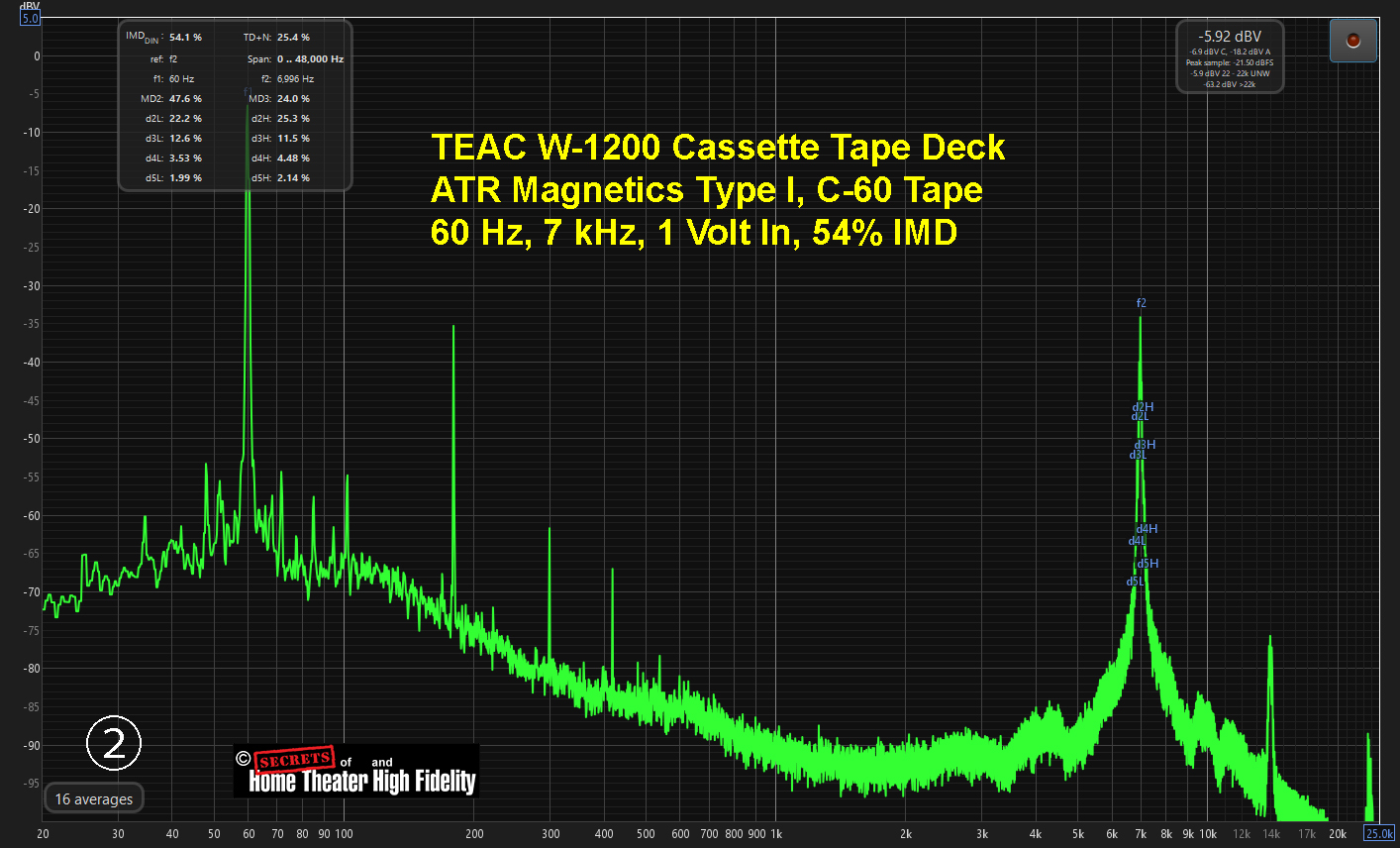

I tested the TEAC W-1200 with three types of tape. (1) ATR Magnetics Type I (Ferric), 120 µsec; (2) ATR Magnetics Type II (Chrome), 70 µsec; (3) RTM (Recording the Masters) Type I. These tapes are brand new. Note that the W-1200 does not have a selectable bias for recording with different bias tapes. I just wanted to see how the deck recorded with them.

Test signals were recorded at 0 dB VU with 1 Volt input to the W-1200.

ATR Type I

At 1 kHz, distortion was 1.88%.

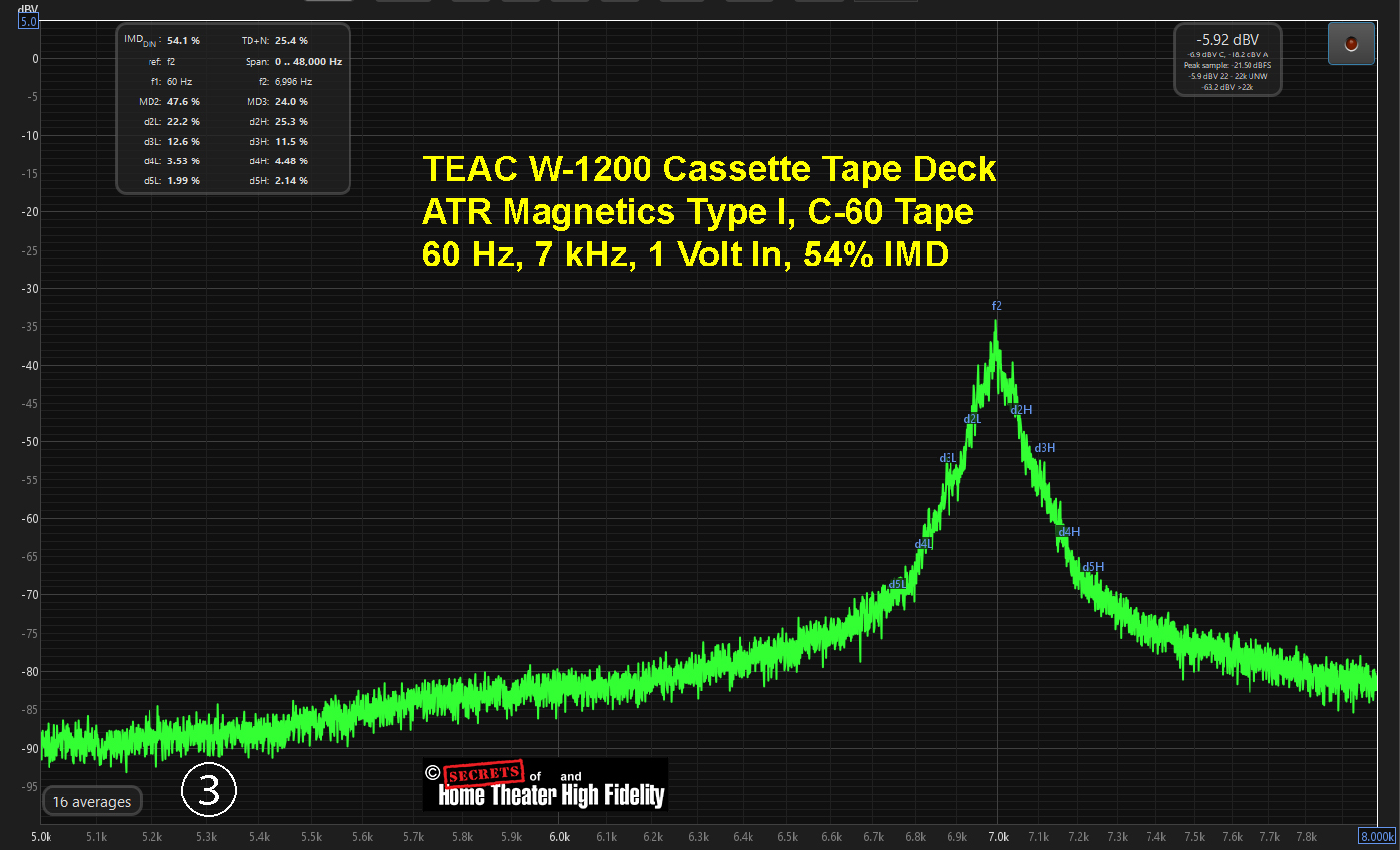

IMD was very high, at 54%. All three tapes had high IMD, and I suspect this is what caused the congestion in the sound. One must keep in mind that a cassette deck is not for recording a symphony orchestra. It is a product to enjoy music with your friends, trade tapes, and listen on the go with a portable player.

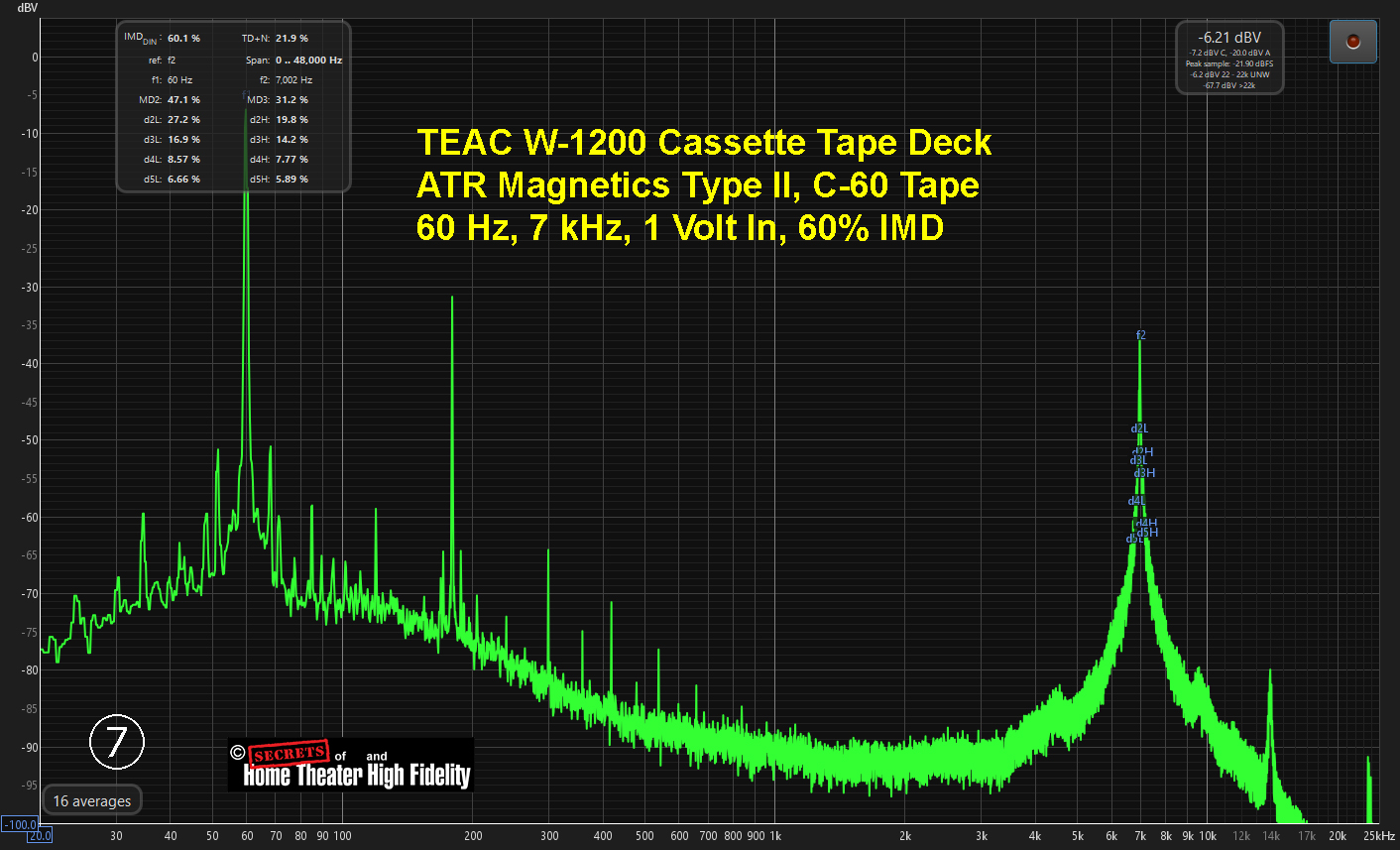

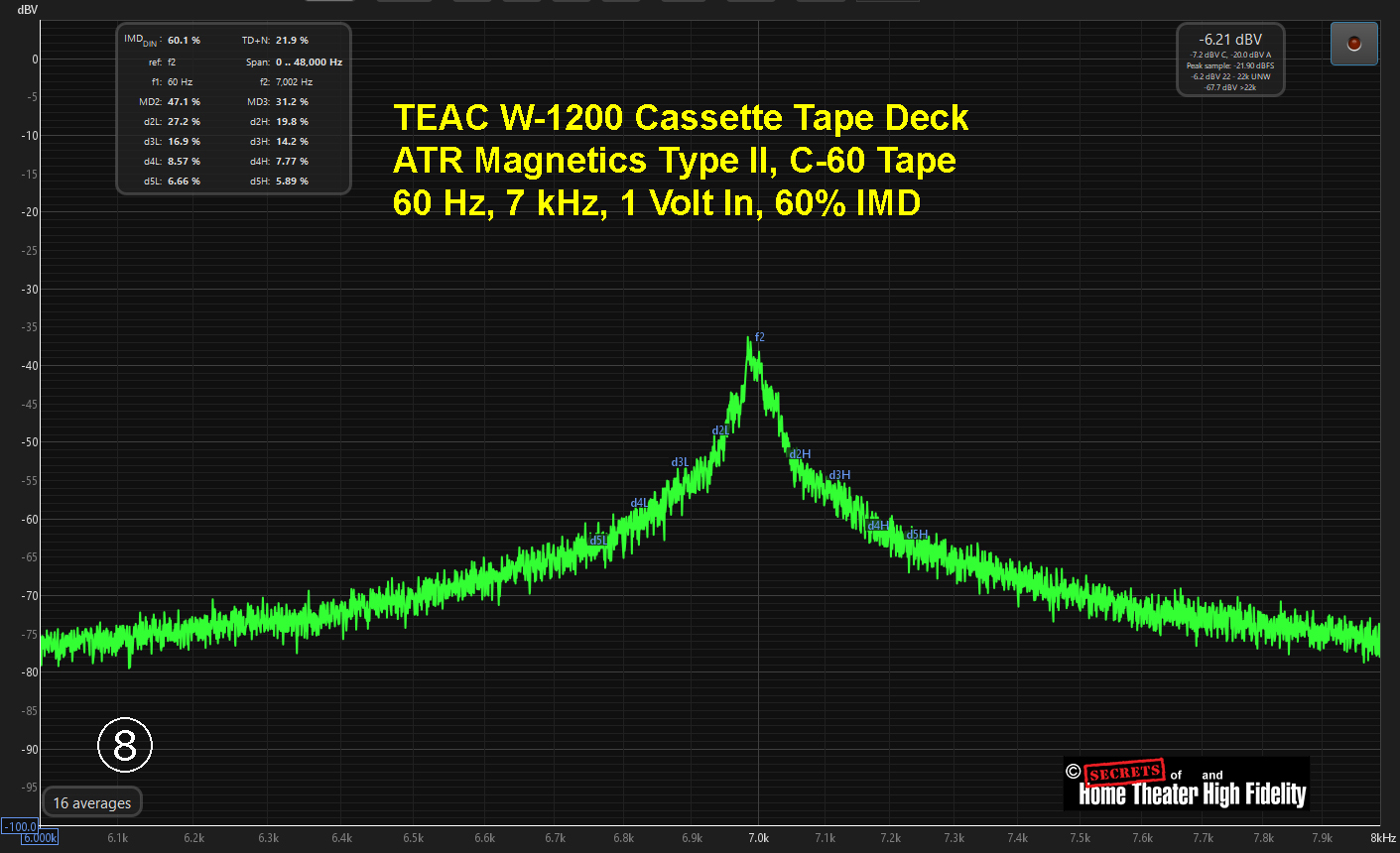

Here is the IMD from Figure 2 with an expanded X-axis.

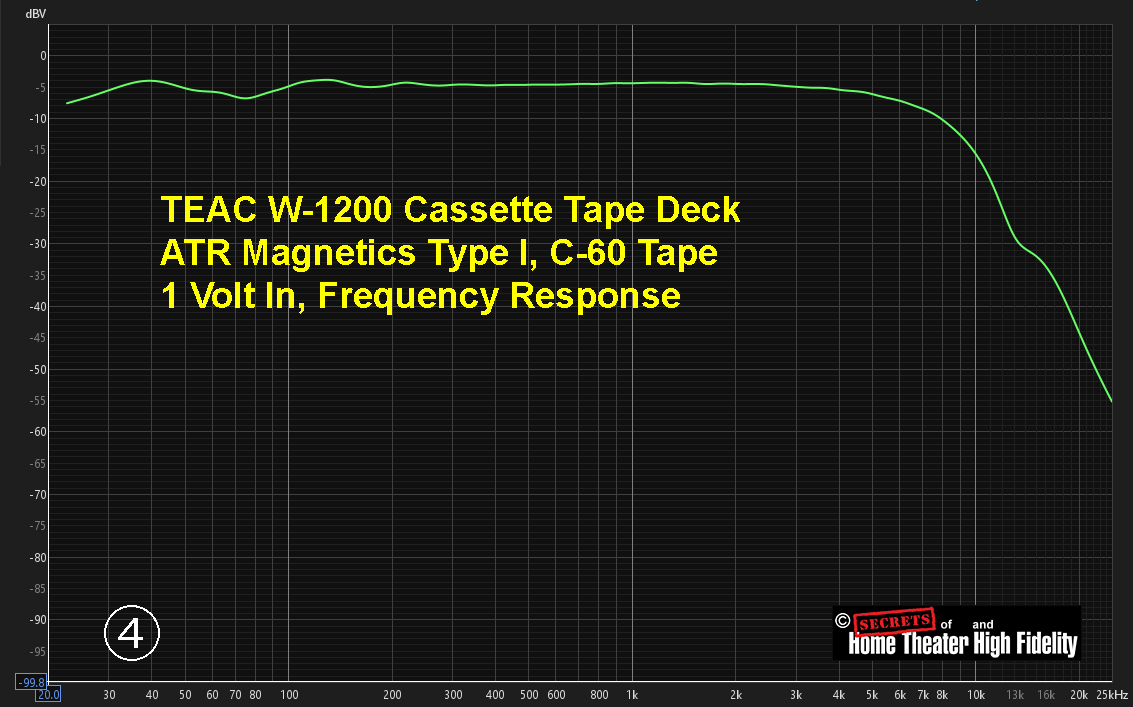

The Frequency Response is shown in Figure 4. It drops 10 dB by 10 kHz.

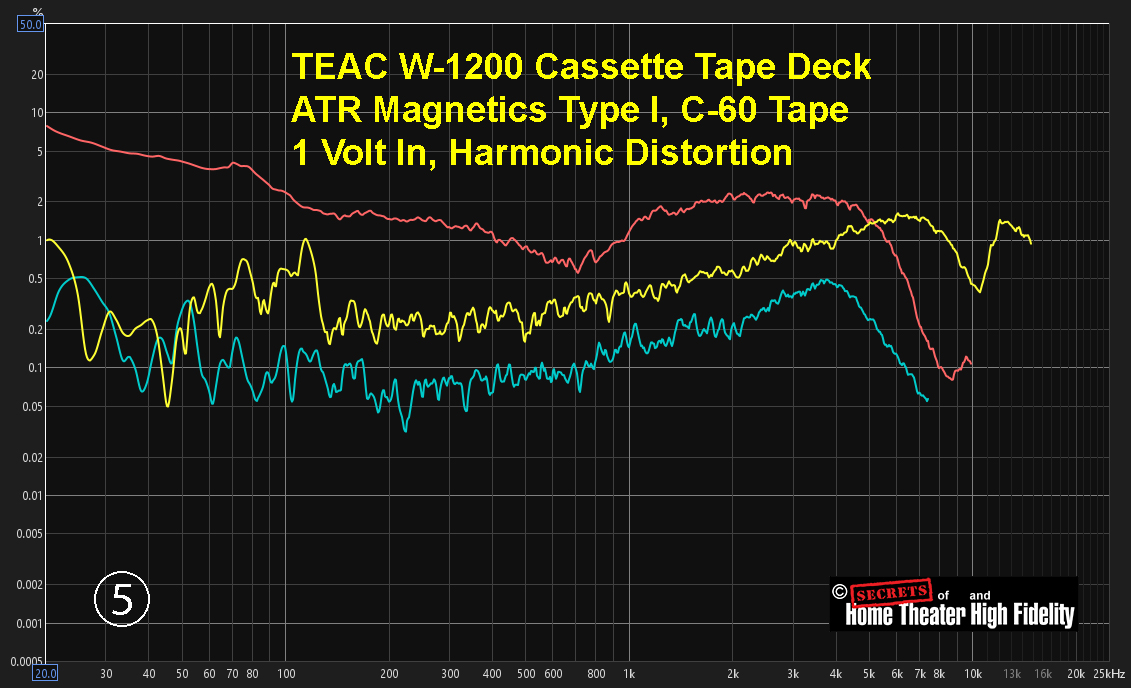

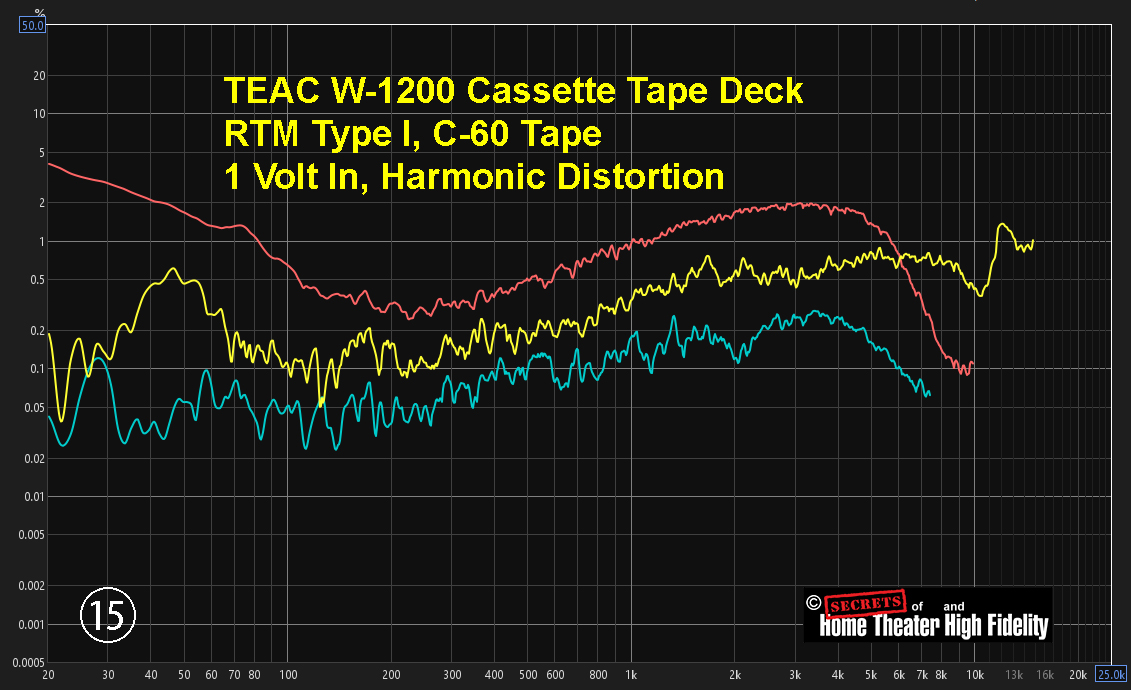

Distortion is shown in Figure 5. It’s high. The yellow line is the 2nd-ordered harmonic, red is the 3rd-ordered harmonic, and blue is the 4th-ordered harmonic.

ATR Type II

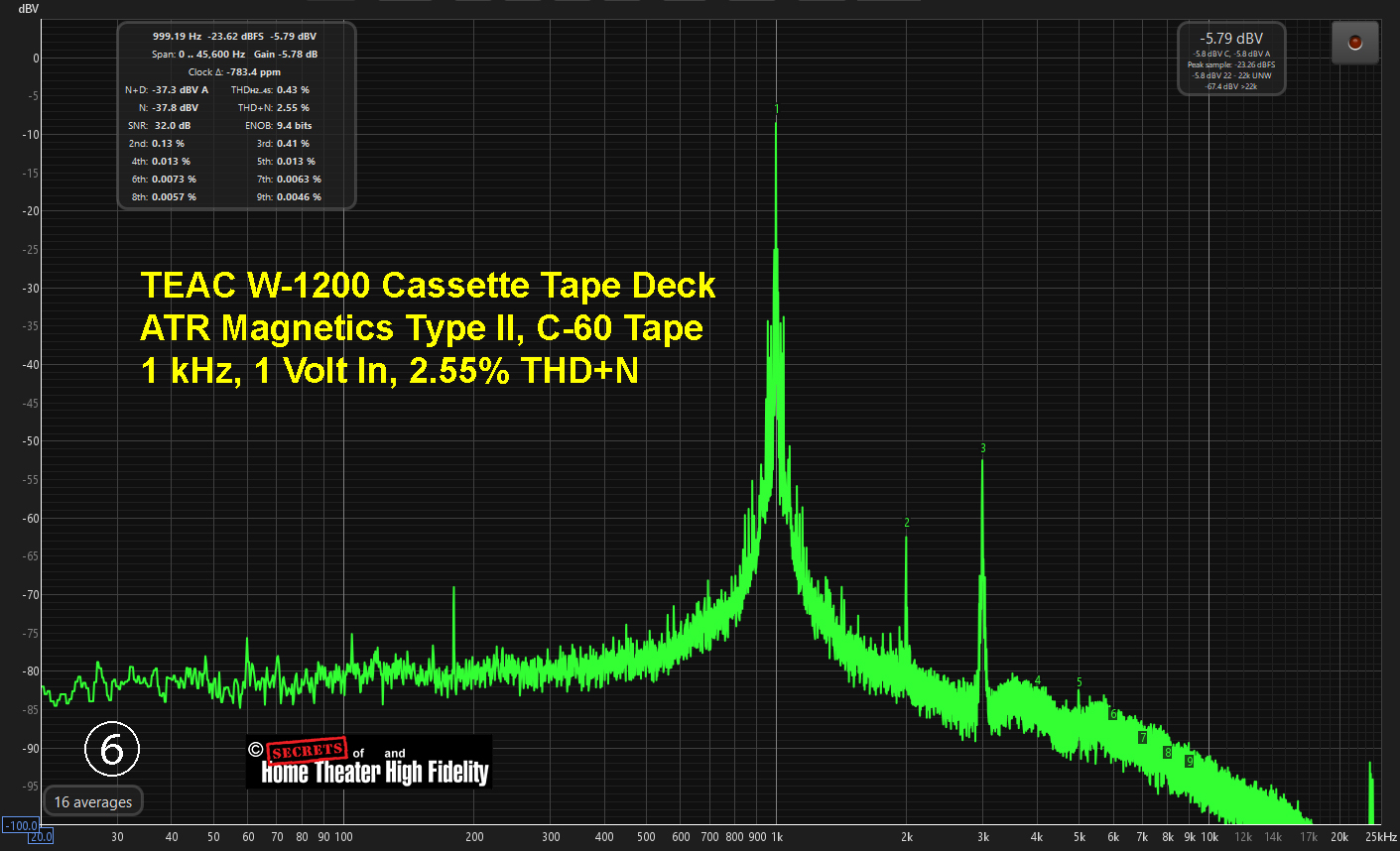

At 1 kHz, the chrome tape yielded more distortion than the Type I tape.

IMD was also higher with the Type II tape.

The expanded scale (Figure 8) shows the IM peaks buried in one large peak.

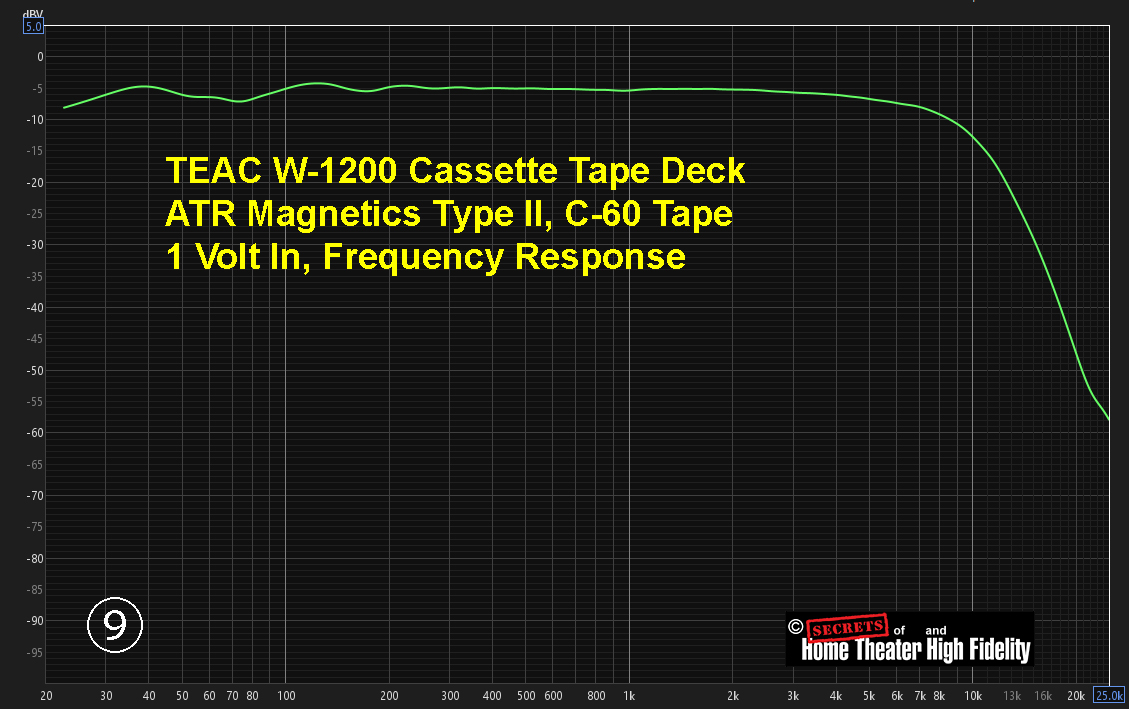

The Frequency Response (Figure 9) is better (2 dB improvement at 10 kHz) with the Type II tape.

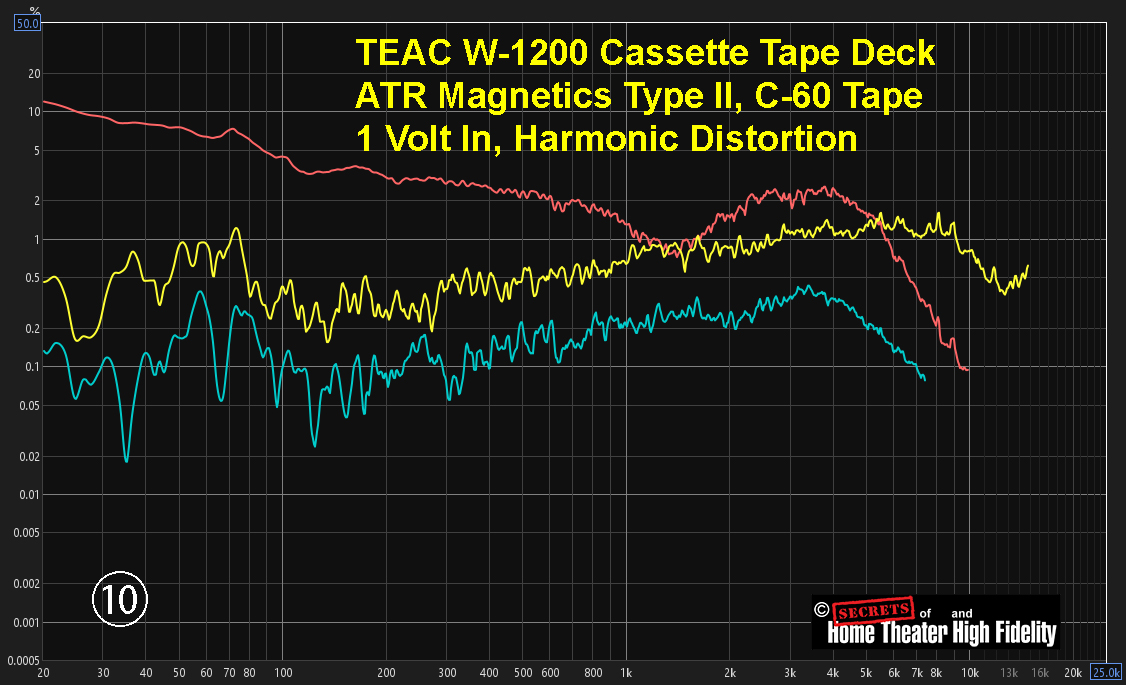

However, the distortion was worse (Figure 10).

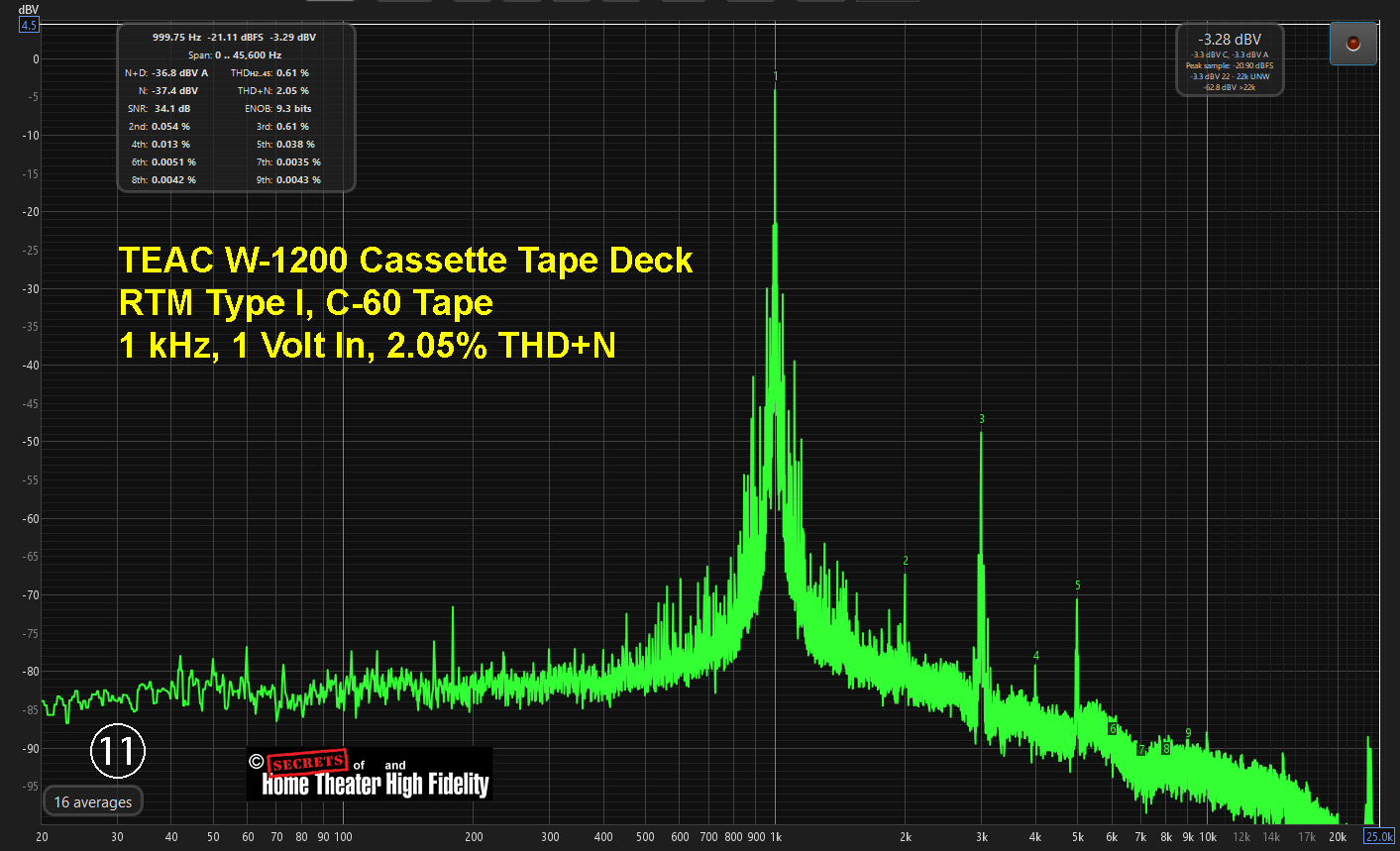

RTM Type I

This tape turned out to have the best results overall.

At 1 kHz, distortion was 2%.

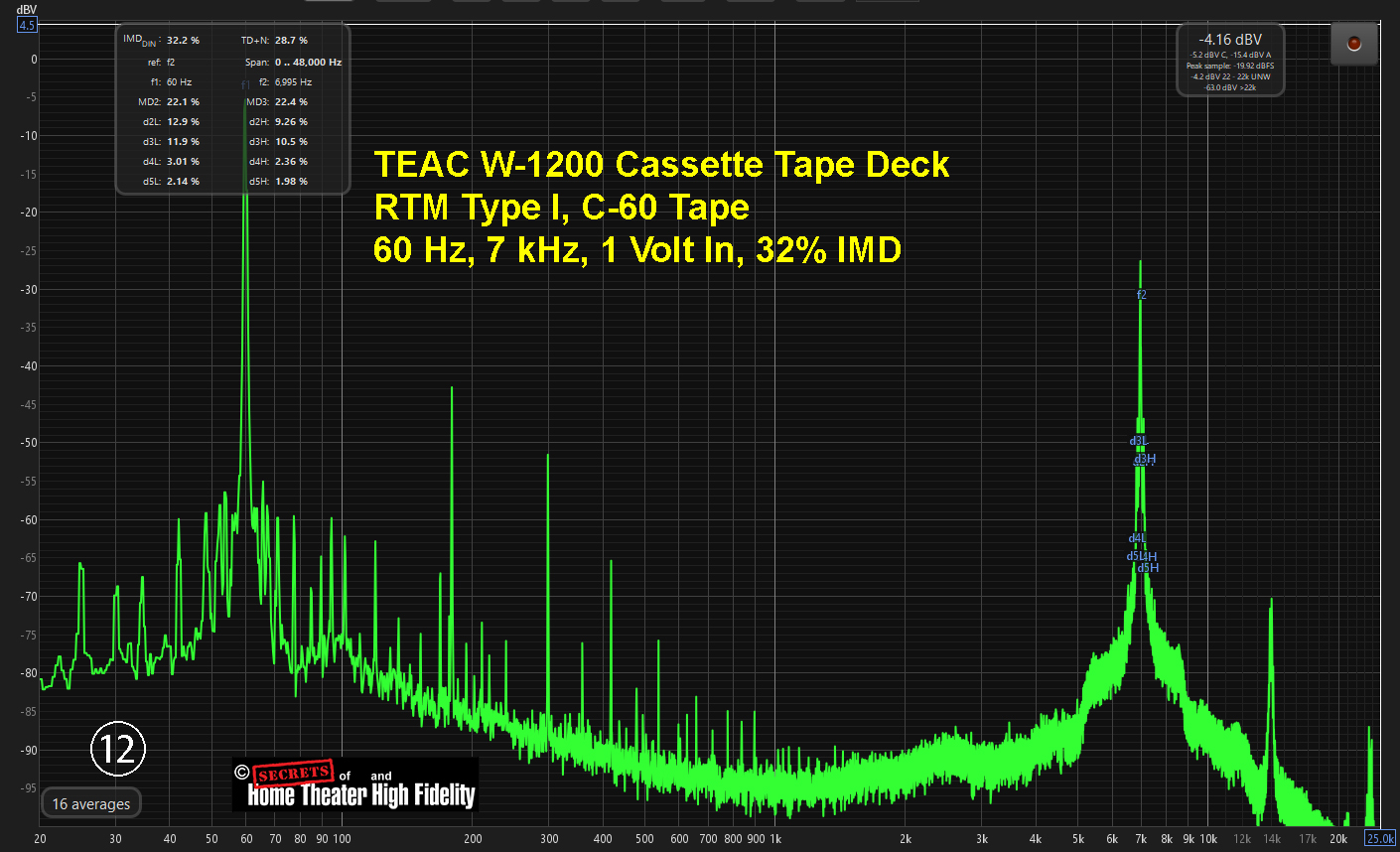

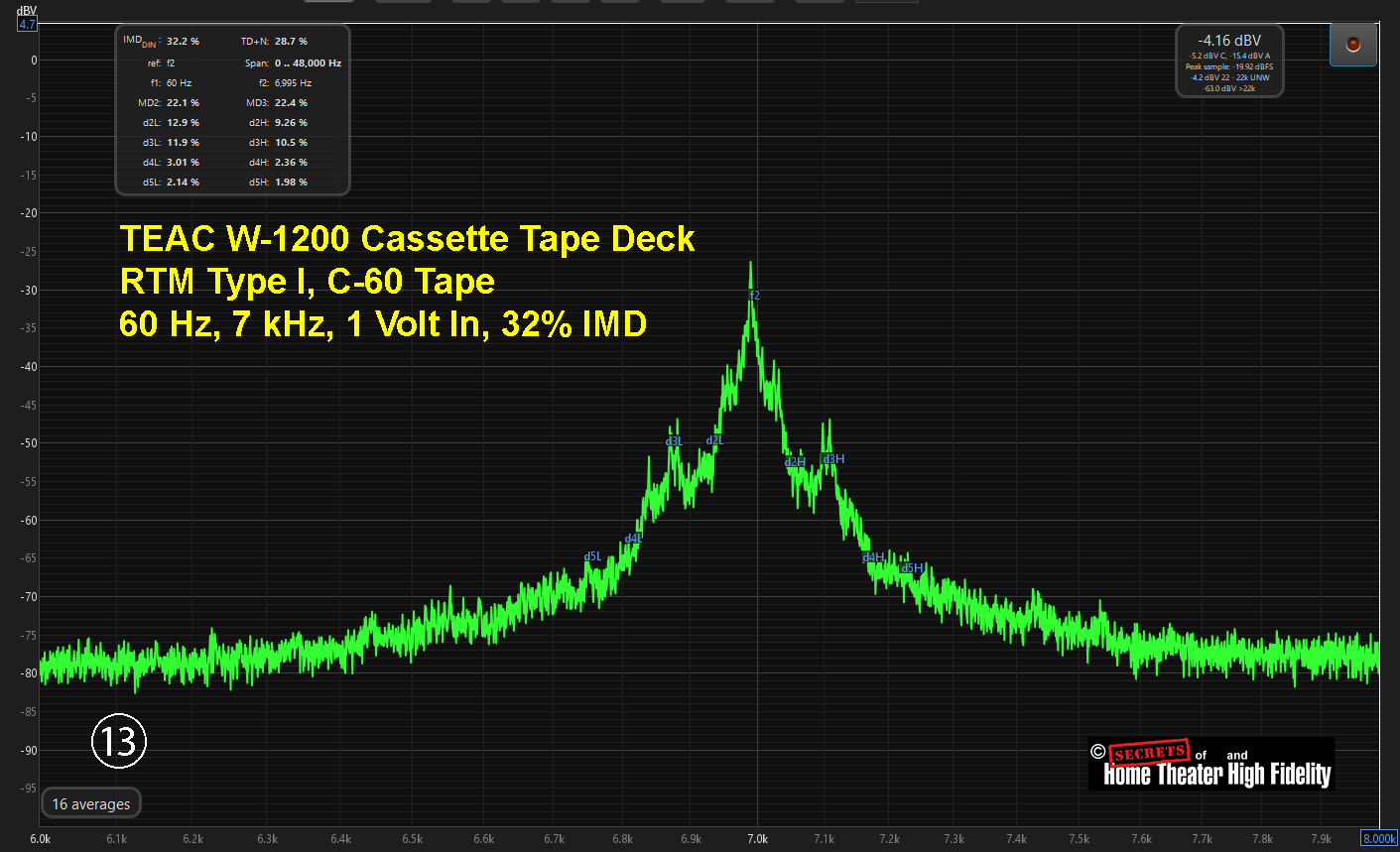

IMD was 32%. Still a high number, but far better than the ATR tapes. Now, I should say that the quality of performance will depend on the tape deck as well as the tape. ATR is excellent quality. I use both ATR and RTM with my RTR decks.

The expanded view shows that the IM peaks are individually visible.

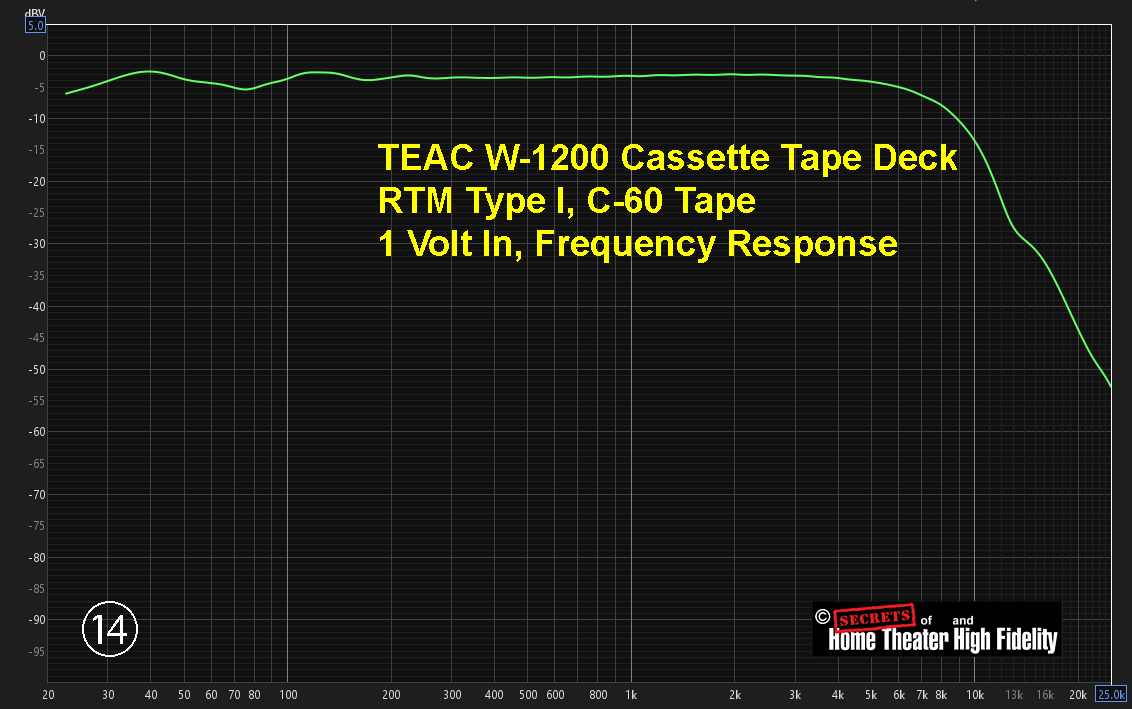

Frequency Response is similar to the RTR Type I.

Harmonic distortion was generally the lowest of the three tapes.

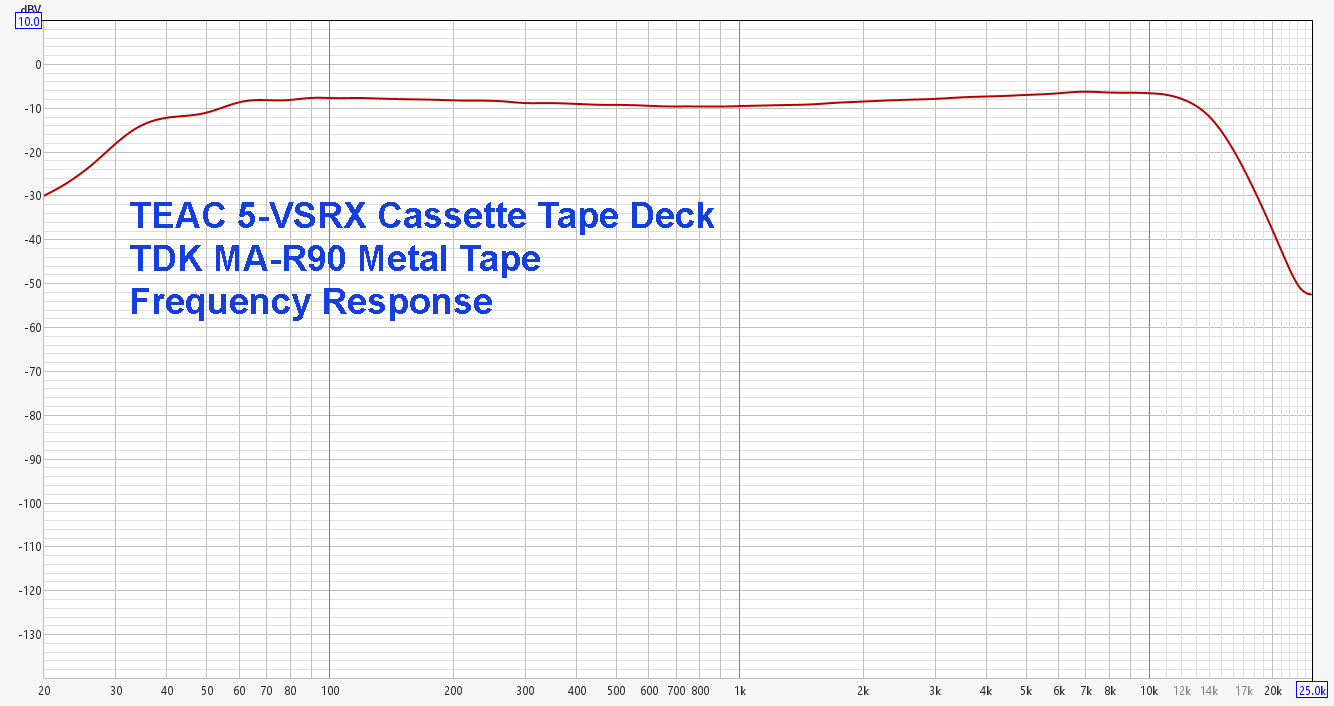

I borrowed a neighbor’s 1980’s TEAC-5-VSRX cassette deck which had bias settings for metal tape. He had some TDK MA-R90 metal tape cassettes as well, so I measured the frequency response, shown below. Notice that the upper response is now within 2 dB of 15 kHz. So, the metal tape and associated high bias do improve the high end. But look at the low frequencies. They roll off significantly starting at 60 Hz. This is one of the side effects of increasing the bias.

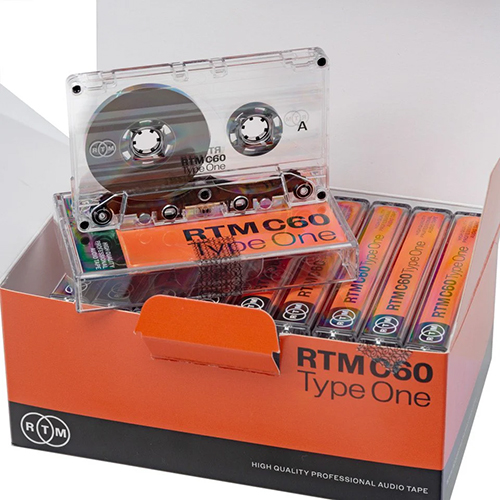

NOS (New Old Stock) tapes are available, but because a purchaser does not know how they were stored, buying them is taking a chance. If you are planning to buy the TEAC W-1200, I recommend getting the RTM C60 blank tape to go with it. They are $12.75 for three tapes. Other decks might do best with one of the other tapes, especially if it has a setting to choose high-bias tapes (chrome).

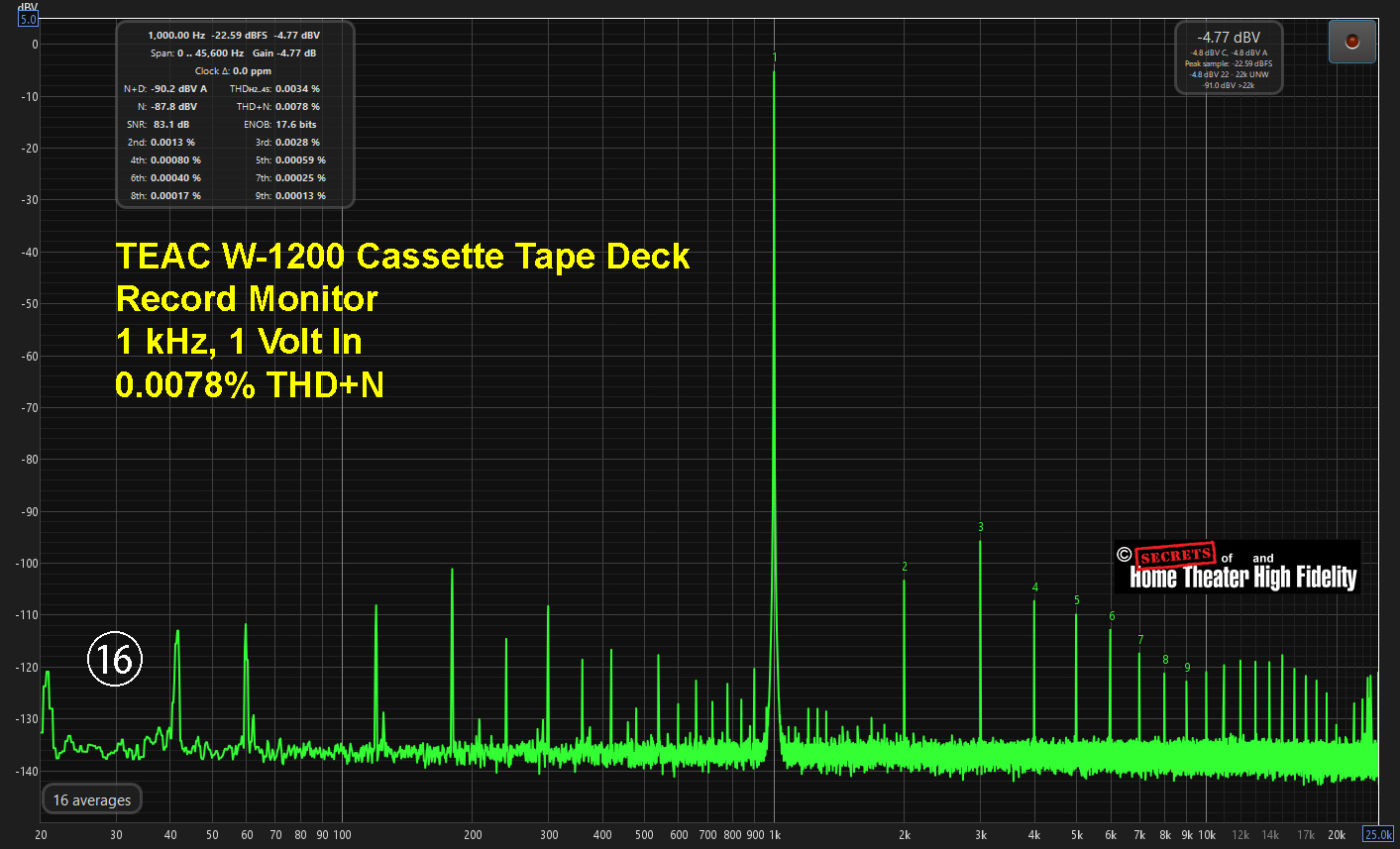

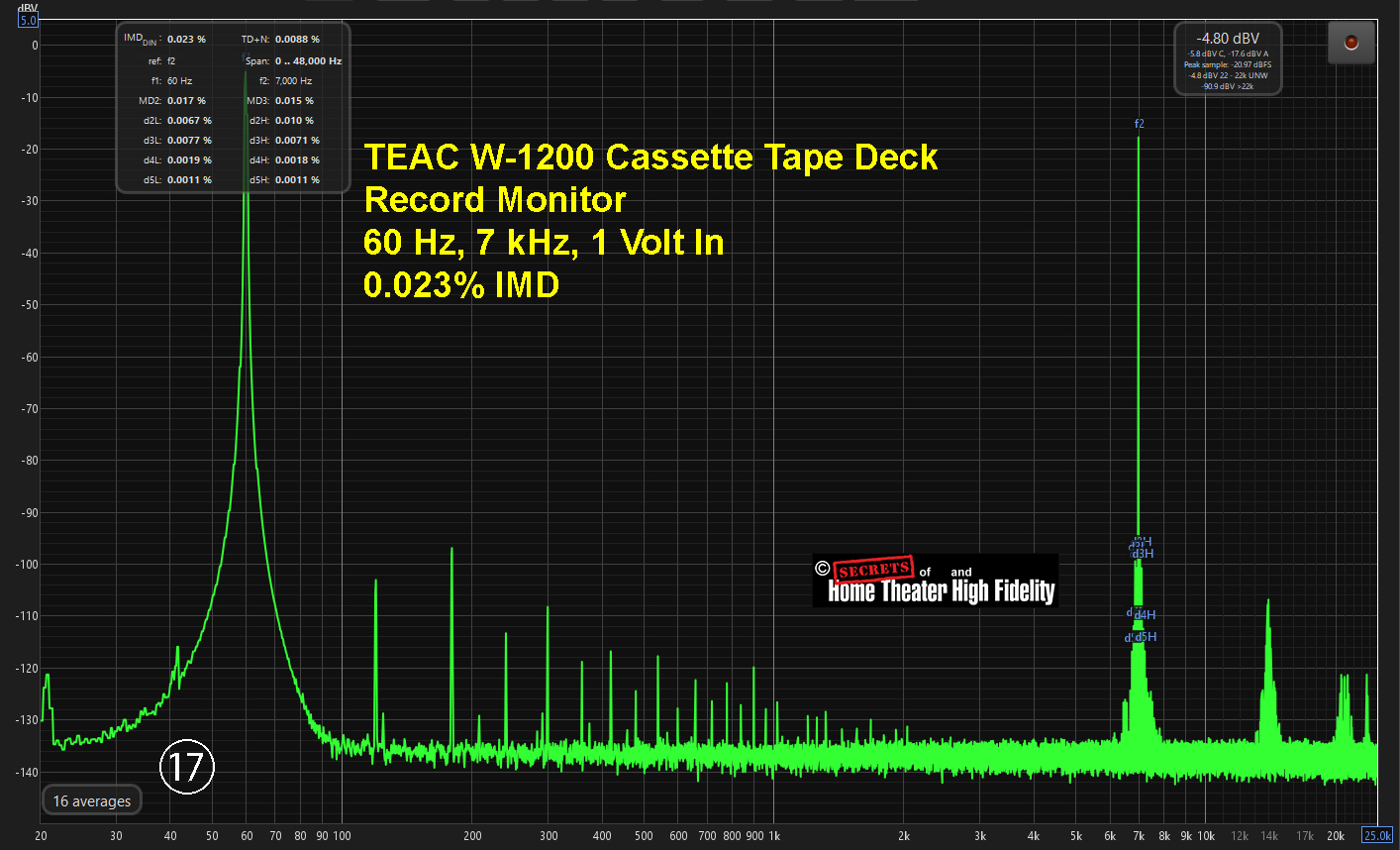

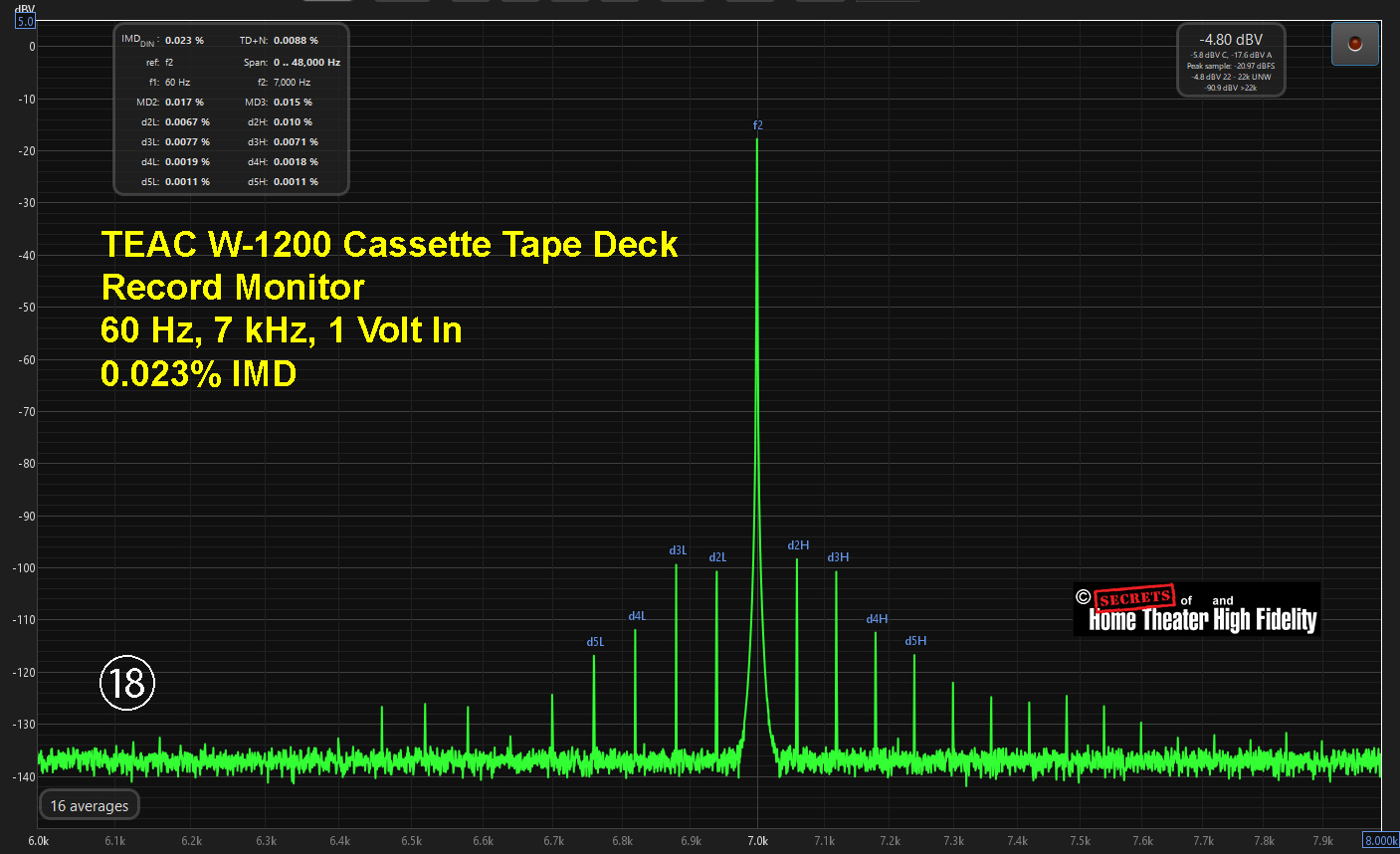

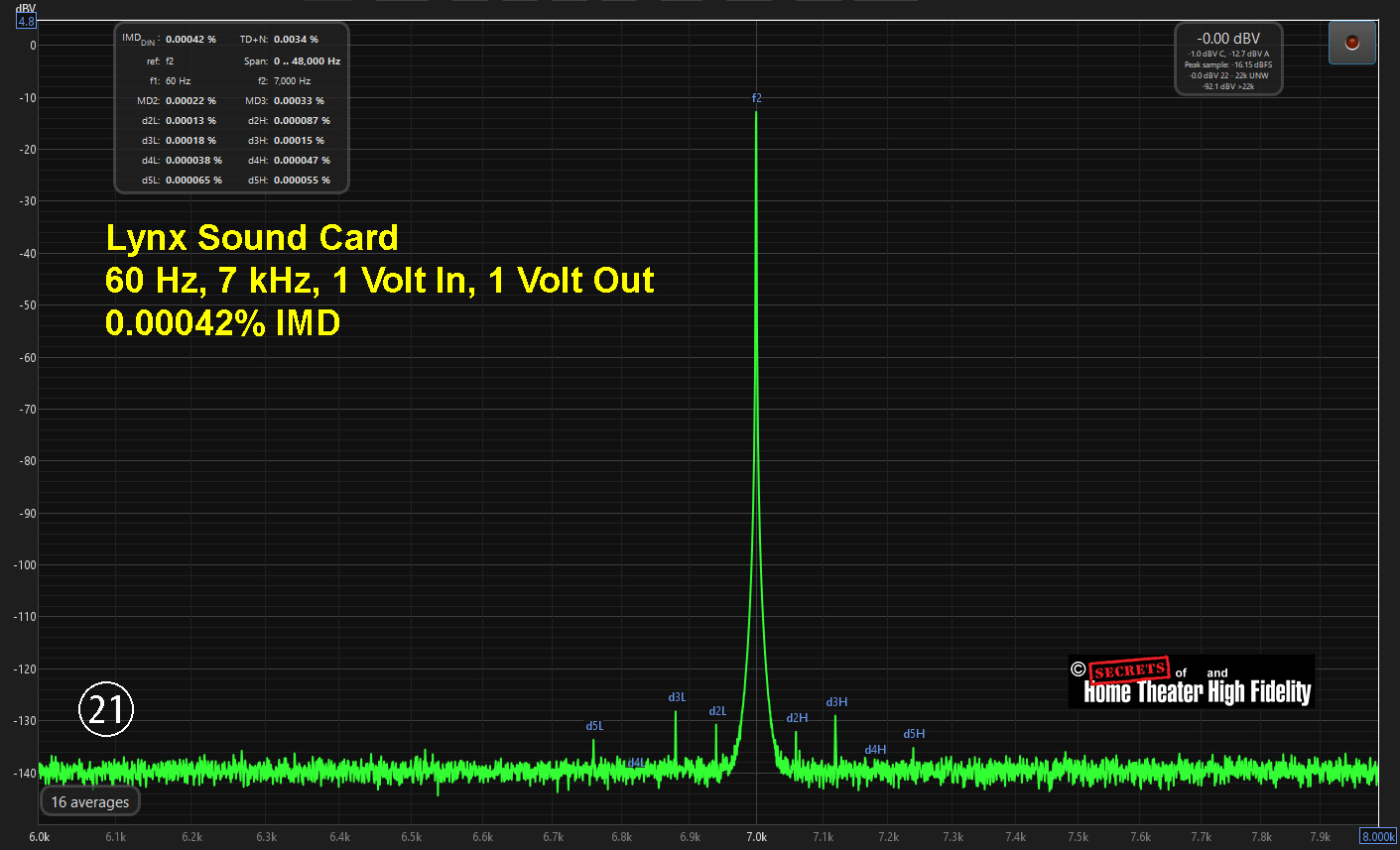

I wanted to compare the bench tests of signals that have been recorded with the W-1200 with the same test signals passed through to the recording monitor circuitry on the W-1200 and also with just my Lynx sound card in the circuit. Here are the results.

1 kHz from the record monitor (the record button was pressed, but the button to start the tape was not pressed) yielded 0.008% THD+N.

IMD was 0.023%.

The individual IM peaks are clearly visible and notice how low the noise floor is compared to playback of the recorded signal (Figures 1-15).

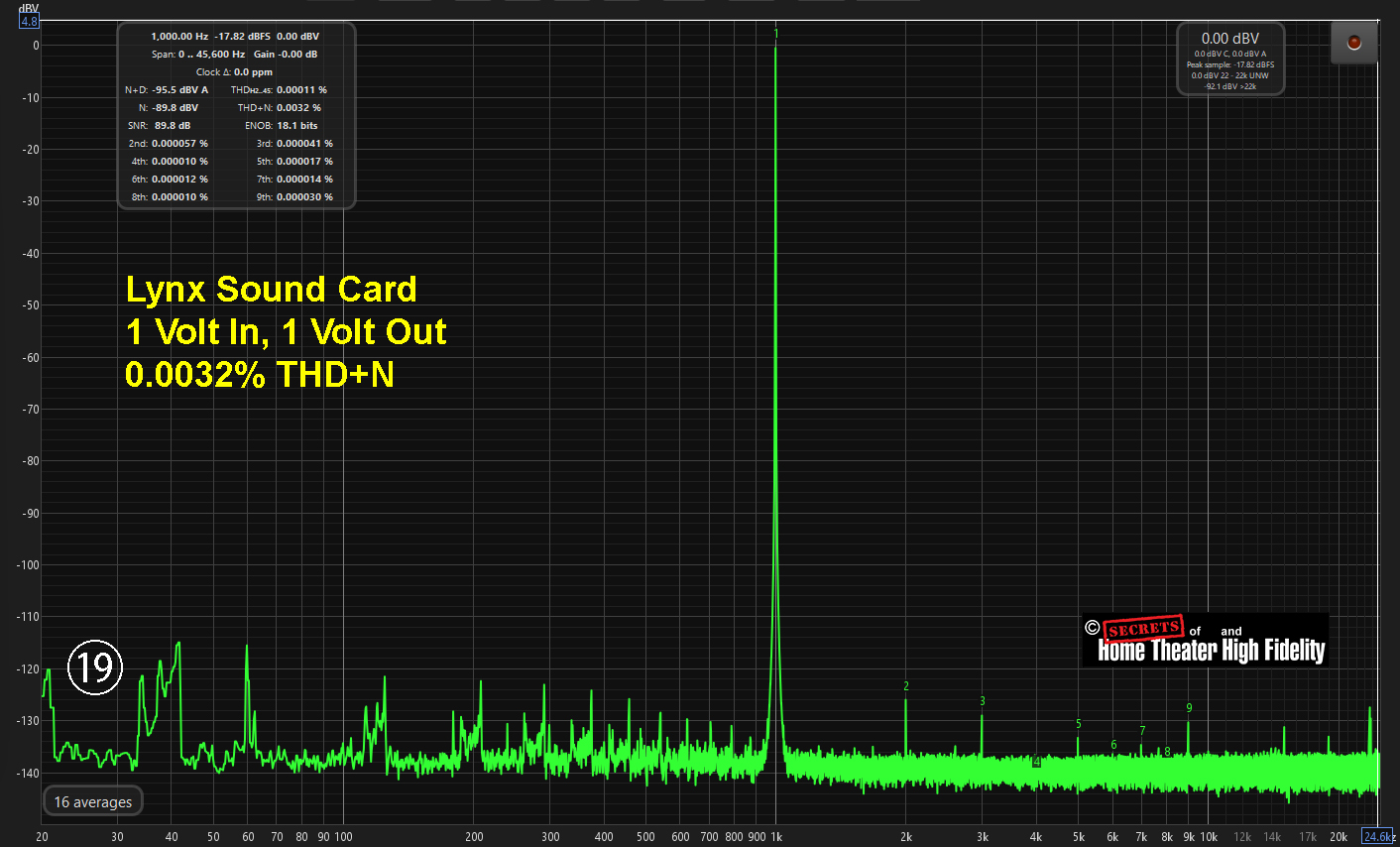

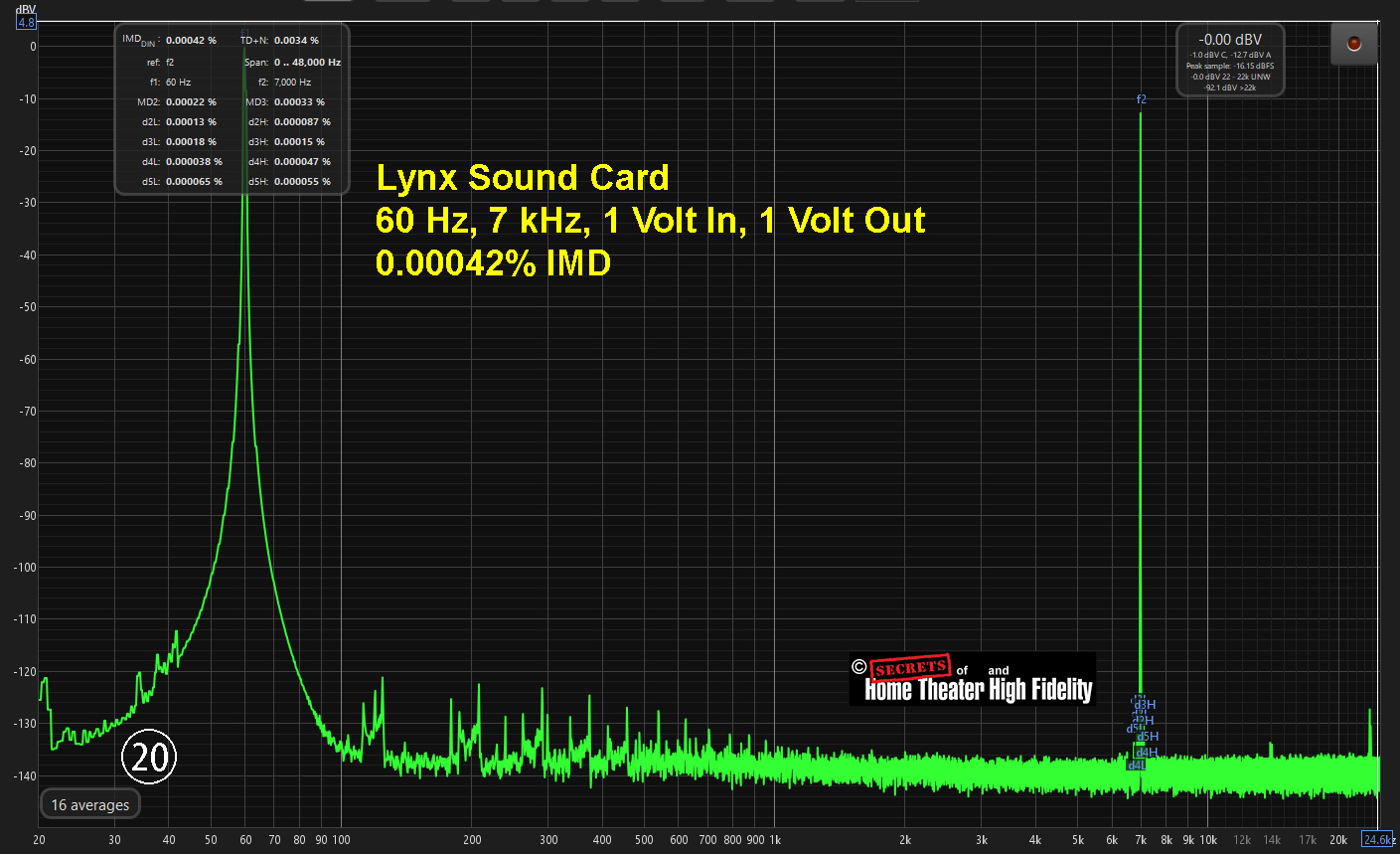

My Lynx sound card has very low distortion (Figures 19-21).

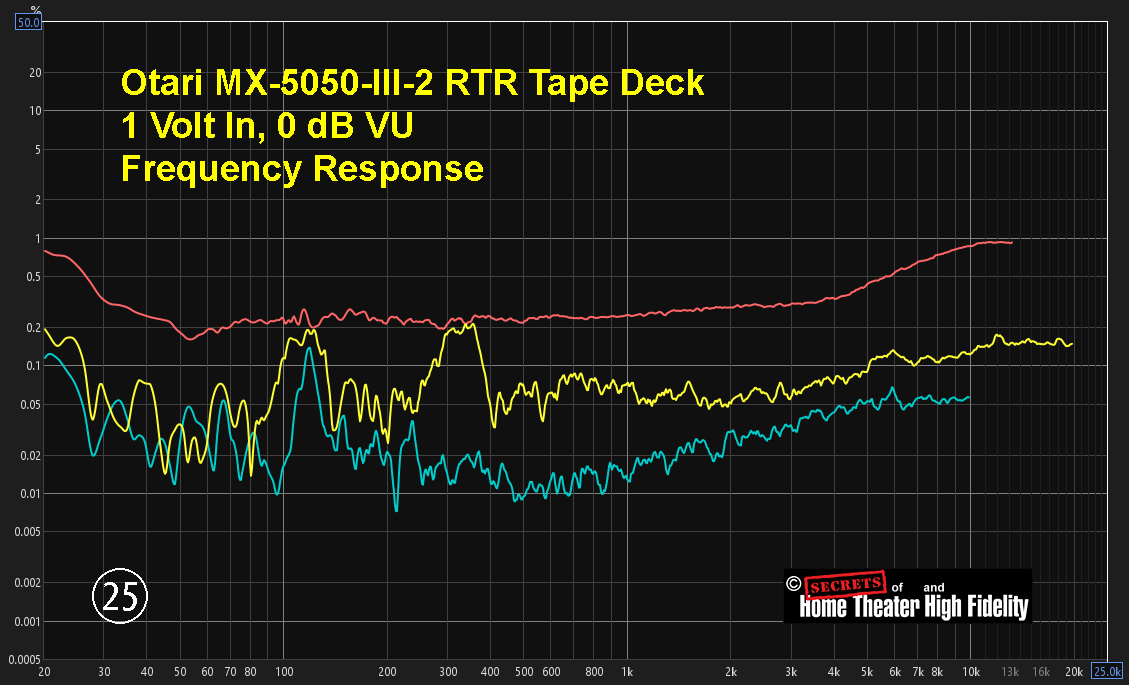

Wow & Flutter was 0.52% which is higher than the 0.25% specification. Wow & Flutter for my Otari MX5050-III-2 (see below) is 0.09%, but it is a studio-quality RTR deck that has a 15″/sec tape speed.

So, the distortion results from the three tapes do represent tape recording distortion and not the preamplifiers. However, as I mentioned previously, the W-1200 is a cassette machine, recording and playing at 1/4th the speed of a consumer RTR (7-1/2″/sec), so this is expected.

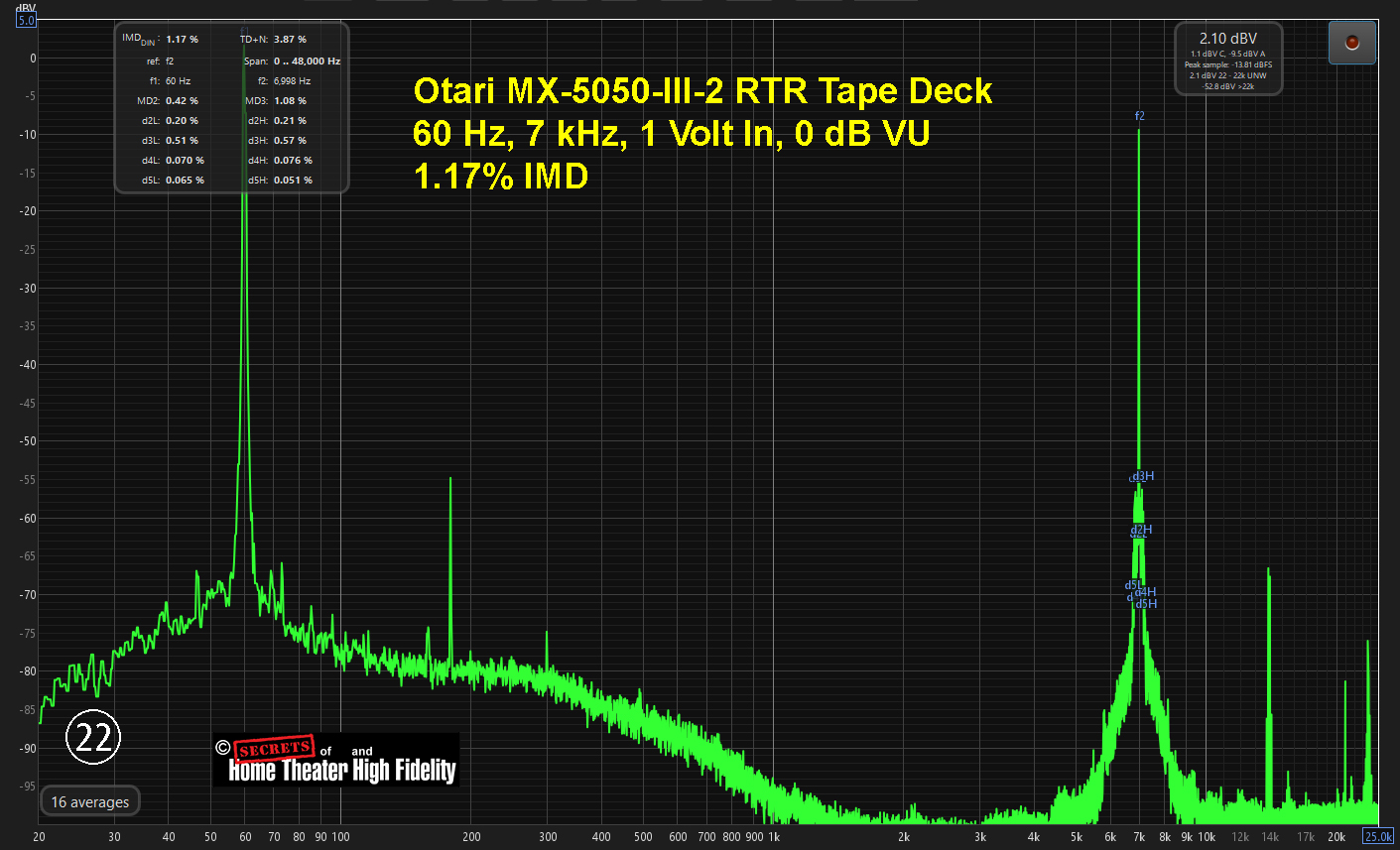

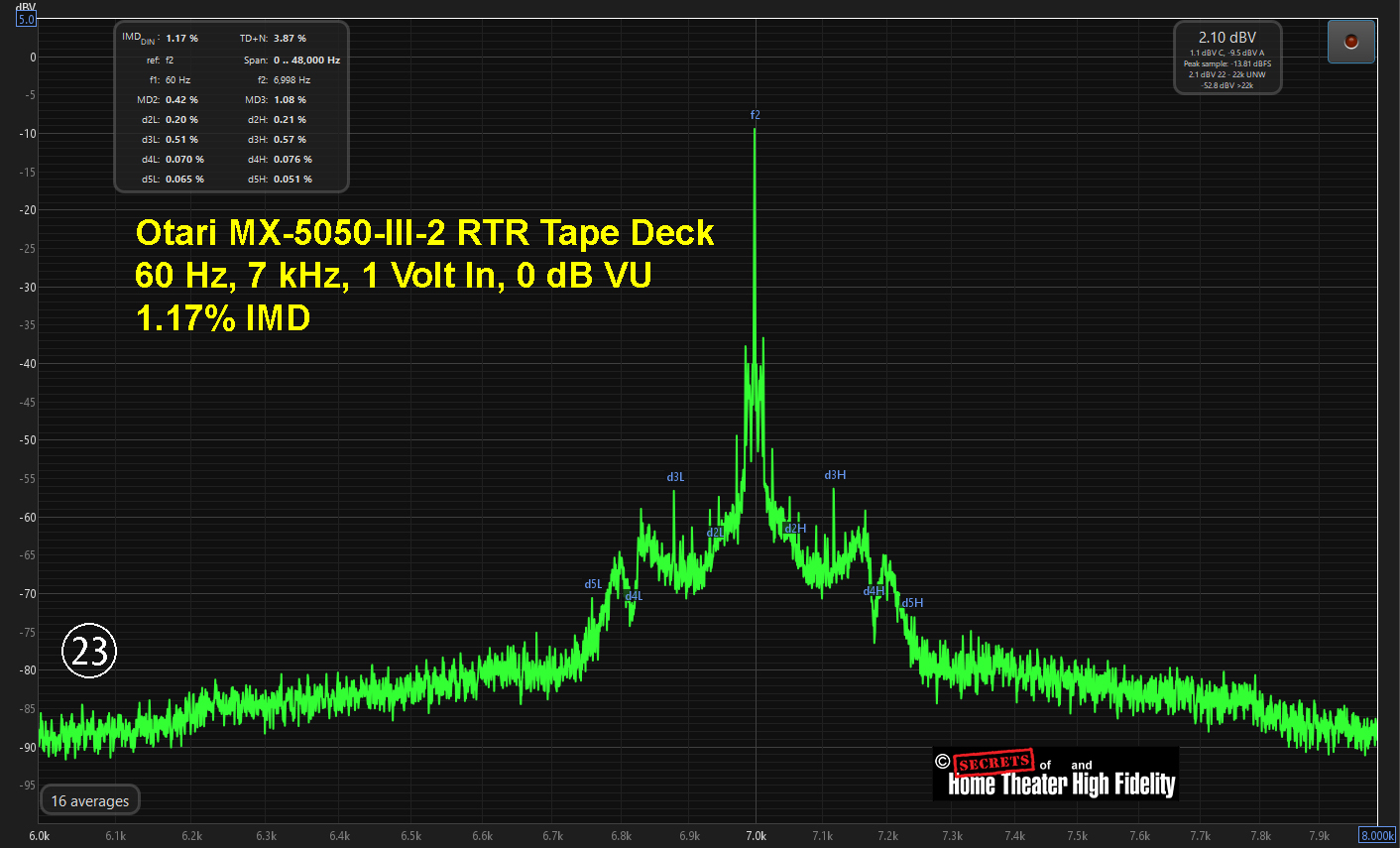

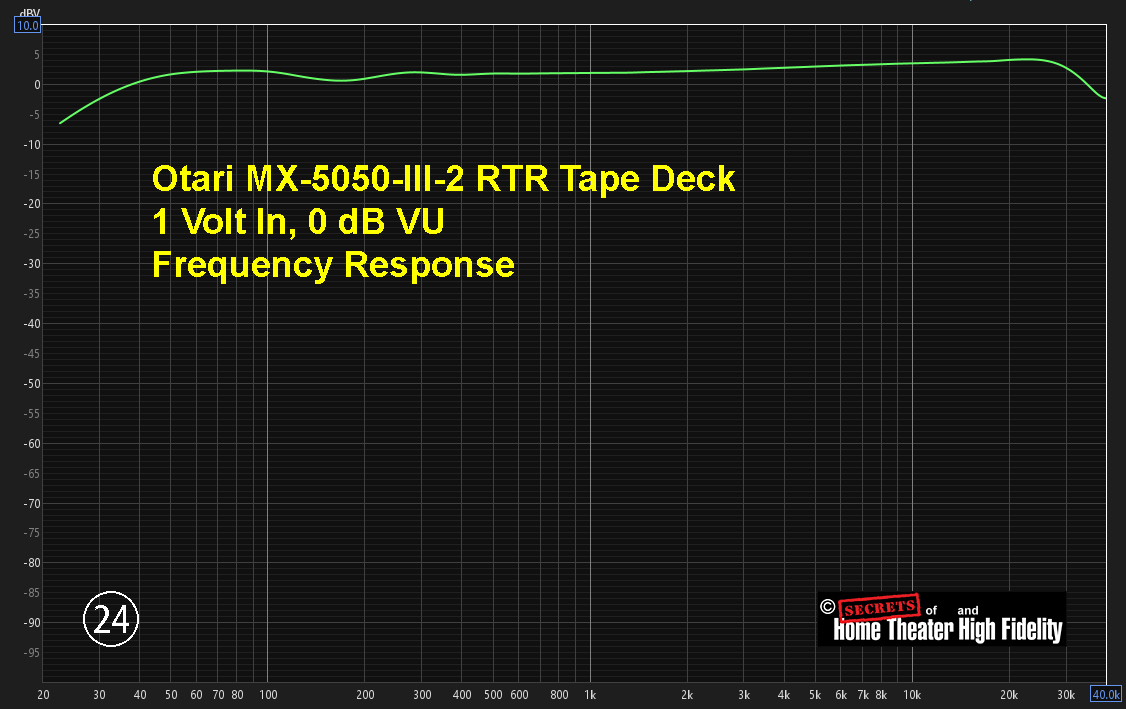

As a comparison with an RTR tape deck (Otari MX5050-III-2), here are the results of IMD, Frequency Response, and Harmonic Distortion tests. I used RTM SM900 tape and a speed of 15″/sec. That is eight times the tape speed of cassette recorders.

IMD was 1.17% (Figure 22).

The IMD spectrum from Figure 22 with an expanded X-axis is shown in Figure 23.

The Frequency Response (Figure 24). It extends out to about 23 kHz before declining. Notice how the bass attenuates starting at 50 Hz.

The Harmonic Distortion. It’s all below 1%. RTR decks and cassette decks have different purposes.

Secrets Sponsor

The TEAC W-1200 Cassette Tape Deck Recorder/Player has plenty of features and capabilities. If you don’t have a deck but want one, this could be the ticket you were waiting for.

- Inexpensive for the features it has

- Two cassette slots for dubbing and parallel recording

- Impressive looks

- Separate head for recording and one for playback

- Noise Reduction for recording

- Selectable bias

- Stereo microphone inputs