Ever since I started becoming serious about audio in my teens, I slowly began becoming more and more interested in understanding what and who was behind the music that I enjoyed. My total consumption by the hi-fi bug happened to coincide with the emergence of the CD format. LPs were on their way out and would not become a novelty interest for me until much, much later. I was taking a high-school electronics class at the time, and the discussion of foundational analog and digital theory was only fueling that interest further.

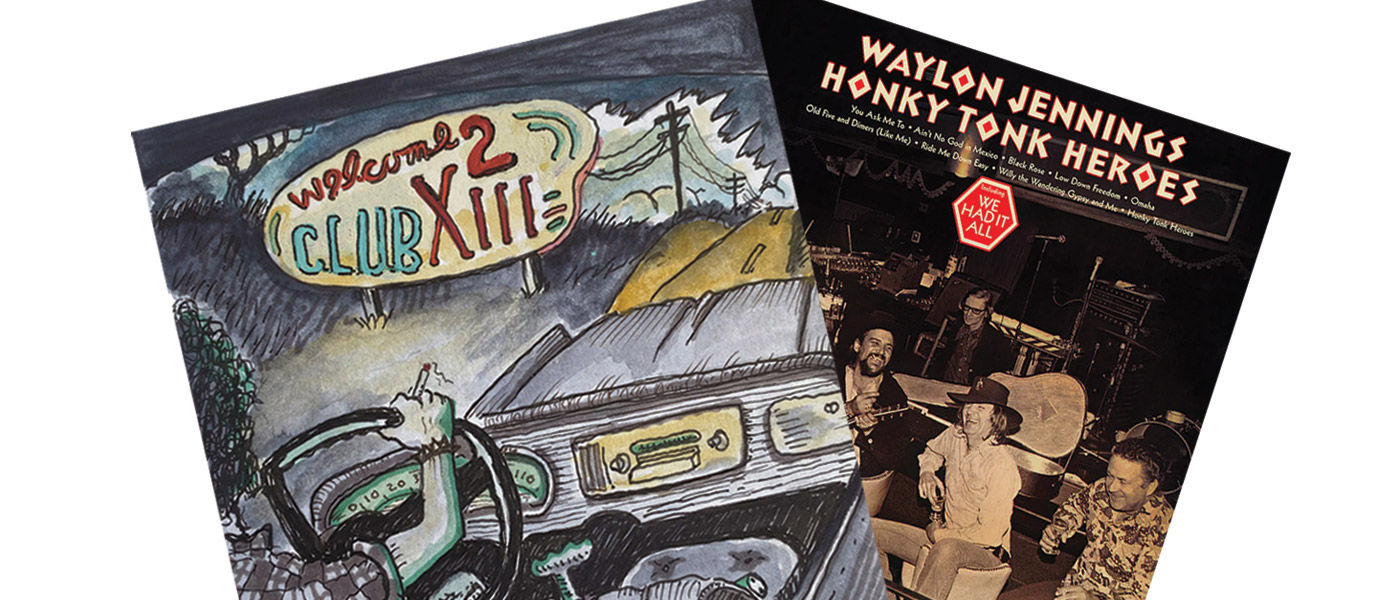

Whenever I purchased a new CD, I would love it when I opened the booklet there would actually be information on the session players, the recording location, process and the recording and mastering engineers. Names like Orrin Keepnews, Creed Taylor, Rudy Van Gelder, Wally Heider, John Eargle, Roger Nichols, Bruce Botnick, Tom Dowd, Phil Ramone, Bob Ludwig, Bob Clearmountain, Allan Sides, Elliot Scheiner, Bob Katz, Kevin Grey, Ted Jenson, Steve Hoffman and Bernie Grundman (to name a few) would make regular appearances in the liner notes of some of my favorite music.

Fast forward to now and having just done a couple of reviews on the Contemporary Records 70th Anniversary LP reissues that were remastered by Bernie, I was offered the chance to interview the man himself. Bernie Grundman Mastering Studios has two locations, one in Hollywood, California and the other in Tokyo, Japan, and they do all manner of digital and analog remastering work for a variety of formats. The word “Legendary” is horribly overused term, and I refuse to use it here because I think it should be reserved for mythology, Shakespearean Sonnets and dead people. To my knowledge Bernie Grundman does not fall into any of those categories. What he has done is amass an enviable record of mastering some of the most popular and well-known music out there. Literally speaking, thousands of albums, along with directly creating and influencing many of the techniques that make up what we consider as modern mastering today.

Talking to Bernie by phone was like talking to my father-in-law, very down-to-earth, quick witted and a great storyteller. We covered all manner of subjects during our extended chat. One note I should mention is that our interview took place before the whole MoFi analog/digital LP mastering debacle, so don’t look for Bernie’s opinion on it here. I never bothered to follow up with him about it because, by now, enough ink and drama has been spilled on the subject and, frankly IMHO, it really is time for people to move on.

Hi Bernie, it’s a pleasure to meet you. First of all, thanks for taking the time to chat with me this morning.

Yeah. Nice to meet you too. So, we were gonna talk about my old, original job in Hollywood at Contemporary? (Chuckles)

Absolutely, if you don’t mind, we can totally start there or anywhere really.

Sure. You know, as a young audiophile way back when high fidelity was coming in (Heh, that’s how long I’ve been around this stuff) those were the albums that really stood out, back in the mid fifties. That’s when Contemporary started really being noticed for their sound quality too.

I’ve heard you mention that, as a teenager you used to hang out in Hi-Fi shops. So, do you consider yourself an “audiophile” as well?

Yeah, well, you know, these kind of hi-fi areas are really what brought me to working in the industry. They really stimulated my interest and just fed my passion for music as well as being able to hear it better and to be more absorbed in it. When a recording sounds really good, it’s just like experiencing an extra layer of awareness and depth in the music that you might not get otherwise. It first dawned on me when I was listening to my dad’s old 78 RPM records. I was fascinated by just the fact that you could put these records on and hear music.

Am I right that at first you were interested in film production before you got into music?

At first, yeah. I was born in Minneapolis and my family didn’t move to Phoenix until 1949 when I was eight years old. So, in those days, movies were a big deal. There wasn’t really any TV, just movies and radio. And so, my mother worked at the neighborhood theater in St. Louis Park, Minneapolis and it was one of those buildings where there was a theater and then there was shops down below. She would work on Saturdays, and I would get my haircut at the local barbershop and then head to the matinee with the rest of the kids. Everyone would be looking at this huge picture and I would be asking myself, “How do they do this?” I was really interested in the process. My mother saw how fascinated I was since I’d be drawing pictures of the movie theater, layouts of the interior, the projector beam and everything. She asked if I’d like to see the projection room one day and I was like “Are you kidding me? Sure!” And so, we just walked down the hall and she opens up the door and it was like, oh my God! I was in heaven seeing all the different projectors and film reels and everything. I was so taken and fascinated. My dad also happened to work at the Minneapolis Chamber of Commerce, and he would bring home a little 16mm projector and all these little film shorts that we would run and watch so that just added fuel to the fire again.

As a kid that must have been absolutely amazing.

Right, right! So then when we moved to Phoenix Arizona in 1949, I saved up my money and when I was about 11 or 12, I bought my own little film projector with sound. At the time, loads of movies were available in 16mm in both black & white and color from the local film library. We could borrow them for free and run them wherever. So, between my eventually working at the film library over the summers and listening to my dad’s Jazz and Big Band 78s I pretty much had my sights set on doing something with movies and film at a very young age.

So what changed?

The big turning point for me was when I was about 14 years old. I was driving my little Kushman motor scooter past a strip of shops, and I saw this sign that said, “High Fidelity Sound Systems.” Oh. And I thought what’s that? I kind of could look in the window from the street. In those days a lot of stores catered to hobbyists, so they had unfinished cabinets in there. They had raw speaker drivers just sitting on shelves, you know by brands like University and Altec, that kind of stuff. I would see those big, coaxial fifteen-inch drivers and things like that which were available as raw stuff you could buy, but they also had equipment that was built up in the cabinets and everything. So here I am, and I just can’t escape that. (Laughs)

It sounds like you caught it bad!

Oh yeah! So, it was the early/mid-fifties and I’m just looking at all this stuff and that was when the first McIntosh tube amplifier came out. Obviously, everything was tubes back then. But I’m walking around and I’m looking at this beautiful looking amplifier along with all this other amazing equipment. The store owner was looking at me, just drooling over all this stuff. He says, “Well here, do you want me to play you something?”

Uh-oh!

Exactly! I said, well, yeah, sure. You know? And so, he played this record, and it was like another turning point in my life. When I heard it, and heard that kind of quality, that was it. Right away. It was like, oh no, I gotta be here. And, from then on, all my money went to audio equipment. And then on top of that, around that same time, I started going to this record shop downtown, my dad would just drop me off, but it was the one main record shop in the city, and I would go in there and I was buying big band stuff because that’s what I knew.

What kind of system did you have at that point?

I didn’t have a great system at the time, but it was okay. I could play 33 RPM records, but I’d taken it out of a jukebox, along with the speakers and the amplifier and all that. And I had put the whole system together in my bedroom. I was listening to Benny Goodman, Ray Anthony and lots of big band stuff.

One day I was at the record shop, I saw this record that just looked interesting to me. I thought, God, this cover looks interesting. It’s so different. And, and on the back cover there were pictures of a couple players. I thought, you know, I’m just gonna buy this thing. I have no idea what it is, but it looks interesting. So, I took it home, and then when I put this record on, I was so shocked that anybody could play like that. That was the second audio turning point for me.

What record was it?

GB: A Study in Brown, by Clifford Brown and Max Roach. Doesn’t get any better than that! Up until that point I was used to hearing shorter, more straight-ahead solos that were less intimate. In Big Band you don’t really have time to stretch. This was probably the first example of Beebop I’d ever heard, and the album took me on an emotional journey. The solos were longer, abstract and had an interesting point of view, but without losing the line of the tune. The storytelling, the improvisation and experimentation were all there, but these guys also recognized and thrived on the rhythm. That’s something that a lot of players today are missing. They can play some amazing stuff and I can respect that, but after a while I get bored. These classic Beebop players knew how to balance feel with intellectual stimulation. Any really good music does that for you.

You know after that point; I really became kind of a real beatnik. I had a jazz club when I was 19, and…

Wait, what!? You had a jazz club? At 19?!

(Laughing) Yes, an afterhours jazz club. You see, I had gotten to know all the local musicians by hanging out in many of the clubs in the south side of Phoenix. It was the black section of town and not a lot of people who looked like me went there but I did because that’s where all the great music was. I went to the black Elks Club and went deep in there to those great barbecue places where they had jam sessions until four in the morning.

That must have been one hell of an experience and education!

Oh, it was! So, this friend of mine and I pooled our money together and we found this whole dilapidated, beat-up strip mall. The thing was it just happened to be right across the street from a real high-end resort whose bar was one of the most popular in the city. And in those days, the bars in Phoenix closed at 1 AM. So, what happened was people would come on over after the bar closed and filled our place up! We’d have bands playing and be packed until four in the morning! And so, every morning we’d be cleaning up out of the bushes and out behind the drapes and stuff, we’d have a pile of bottles, everybody had a great time, you know, it was a lot of fun. In the end though, it only lasted about a year and a half, it was a kind of fad of Phoenix, and it had pretty much run it’s course.

Out of curiosity, did you record any of this stuff?

Yes, I was also doing some recording with some of the semi-pro equipment that I had bought and collected up until then. I was recording stuff both at the club and at other events in and around town. High School band performances and those sorts of things.

So where did you go from here.

Well, I guess you can say I got kind of sidetracked. I ended up joining the Air Force. My family needed money and I had high grades in the math and sciences testing that the Air Force gave. So, I enrolled in the forces’s electronics school and eventually got to working in electronics warfare on B-52 bombers. By the time my three-year stint in the Air Force was up, I had made up my mind that I wanted to be a recording engineer. So, I got in my car and I went straight across to Seattle, where I stayed for a couple days with some relatives and then I went down to Hollywood and I drove right in front of Capitol Records. I walked in and went in to see the Head of Recording. I said, okay, I wanna know what I need to do because I want to be recording engineer!

Well, that was a pretty bold move!

Right! I’ve always been pretty driven, especially as a young kid. It must be the German/Scandinavian heritage. In the end we talked, and he suggested I go back to Phoenix and take a degree in Electrical Engineering. So, I enrolled at Arizona State University and took a ton of math courses, among the other things I needed to get my degree.

While I was at University, I happened to call up a local studio that had done some work for me in cutting a master for a High School band recording I had done prior to entering the service. So, I spoke with the owner, his name was Floyd, and reminded him that we’d worked together on this High School band thing over four years ago, and I asked him about how I could learn more about being a recording engineer. It was really important to me, and I wanted to learn all I could. Floyd says back to me “Well, you really ought to speak with Roy DuNann.” I said, “Wait, What?!” And he says “Yeah, Roy DuNann works here.” I said, “I’ll be right over!”

Wow! Talk about, right place-right time!

You’re not kidding. So, when I got down there, I said, look Floyd, I gotta work here. I don’t care what I do. You don’t have to pay me. I can clean the toilet. I don’t care. I just wanna be around Roy DuNann! Roy engineered all the Contemporary records releases. He ran Capitol Records engineering all through the forties up into the early fifties. Then Lester Koenig took him away to build Contemporary around 1952 or 53. But right now, here he was in Phoenix having moved because of his first wife’s health issues. And he was working at this local studio, recording radio commercials and Country & Western stuff! So now, I started coming in whenever I wasn’t in class at Arizona State and just tried to absorb everything I possibly could from him.

One Monday I came in and he says “Oh, I should have told you, over the weekend Howard Holzer was in town.” Now Howard was the other key guy at Contemporary. Both Roy and Howard put together the first stereo disc-cutting system on the West Coast.

Oh wow!

It was based off of a Westrex cutting head originally developed by Otto Hepp, a German immigrant. But Westrex hadn’t figured out how to make it work in stereo. They hadn’t built the amplification and feedback systems needed to get it to work but Roy and Howard figured it out. They were both brilliant in electronics and Roy especially could do anything. He was known around Hollywood as the guy that could do tape editing like nobody else, even classical music. He could record, he could edit, he could build the equipment. He was almost a one-man studio. Anyway, Roy told me that all Howard was doing now was building cutting systems out of Van Nuys, California. His company was called Holzer Audio Engineering and I decided right there that I needed to go down and see him in person.

Just like that?

Yup, just like that. So, I drove out to Van Nuys and walked into his office wearing a suit and tie. Now, Roy had told me that Howard was kind of a bull in a China shop, a real gruff kind of guy. And here he is out in his shop with a t-shirt on, eating his lunch out of a soup pan with a spoon. (Laughs) And here’s this beautiful cutting system right behind him, but here’s Howard in the flesh. I said, “Gee, you know, I wanted to introduce myself, you know, because Roy told me about you.” And he replies, “Yeah, I know Roy and he told me about you.” And I said, “Oh, really?” Howard then says, “You know, Lester over at Contemporary, doesn’t have an engineer at the moment. Why don’t you take that job over there?” And I say, “What? Wait a minute, I’ve been hanging around the studio a couple months. I’m just winding cables and trying to learn stuff.” And he says, “Look, if you love your job, and you’re passionate enough, you’ll figure out how to get there.”

That advice just made me want to work harder at finishing my degree and learn all I could from Roy. My family had always been a little dysfunctional, but I was lucky in that they pretty much let me do what I wanted, and they didn’t really put up any roadblocks. So, I got back in my car, went back to Phoenix and just worked my butt off between school and helping Roy out in the studio while he was recording, just asking questions and doing as much as I could.

So midway through my final year at school, I call Howard up and ask him if he could set up an interview with me and Lester Koenig once I wrapped up my exams in August of that year. He says, “No problem! You know Lester is picky and a little hard to work with, but I’ll be happy to set it up for you, no problem!” So that’s fine and I keep working and eventually get to my last two weeks before exams, and I’m nervous, wondering if Howard ever got around to setting up that interview. So, I called up Howard and I ask, “Howard, you know, I’m getting out in a couple weeks, I’ll be done with final exams, did you get that interview with Lester for me?” He says, “Hey, I got you the job! When can you start?” And I said, “What!?” I thought, oh my God, what are these people seeing in me?

That’s just unreal. That’s awesome. That is so awesome!

It was! And so, in September, here I am with my car and a trailer and all my stuff, my equipment and so forth, moving to LA.

You must have had quite the array of gear by then.

By the time I left Phoenix my stereo setup was a pair of Bozak Concert Grand speakers, with a total of 28 drivers (14 in each cabinet). I had a pair of turntables and a full Marantz amplification system. All crammed in my 12 x 12 bedroom!

That’s nuts! Okay, so now that you got hired at Contemporary what did you start doing?

Absolutely, so here I am at Contemporary, and I’m working for Lester, but what we’re doing primarily there is keeping the catalog up. I worked at Contemporary for 2 years and only recorded a few albums there. Most of what I was doing was remastering because in vinyl you always have to keep cutting new masters as the LPs are selling. The stampers wear out and you have to make another master and they have to process it and make more stampers to keep production going. So, I was doing a lot of that and I got to work on a lot of very famous albums and so forth, but it was really after they were already recorded.

What made the Contemporary “sound” so special?

The thing about Contemporary, that was interesting at the time, was that everything, the equipment and the process, was hand built by Roy DuNann and Howard Holzer, primarily Roy. Now for mastering, they put together a setup that allowed for a large degree of manipulation. This is common now but at the time it was a state-of-the-art mastering room they built, and it allowed us to do all kinds of things. For the recording end, and because it was for jazz recordings, they were keeping it as simple as they could, with a very clear signal path so the final sound quality wasn’t interfered with. Roy, whether by design or necessity, was very good at being a minimalist and knowing how to put things together, that weren’t gonna cost a lot of money. I think at first, he didn’t know how great it was gonna sound. But the recording techniques they came up with created a wonderfully natural sound on record that really stood the test of time. And Contemporary quickly gained a reputation for having some of the best sound quality out there.

I believe you guys started attracting a lot of outside work because that, correct?

Yes. because Lester wasn’t really doing a lot of new recordings at the time I was there, he opened the studio up to custom work. So, anybody that wanted could use Contemporary for mastering. And that was the only room that was pretty much state-of-the-art. And it had all this manipulation possibilities. So right away, everybody got word around the city because they knew Contemporary had a good reputation for sound. So, all of a sudden I started attracting all of these people. I was doing work for The Doors, Herb Alpert, Dionne Warwick, Procol Harum, you name it!

Secrets Sponsor

That sounds almost like the Golden Age of mastering. A very creative time.

It was. And because we were a small studio, we were forced to be creative and were doing all sorts of things that a “mastering engineer” wouldn’t be doing in a big, regimented studio like RCA or Capitol. Lester and I would sometimes take a day or two to cut one album because we would have to choreograph each tune because you know, each tune has to be played in succession. You can’t stop the cutting lathe like you can stop a digital recorder. So, you had to have it all mapped out for each tune. We do “this” on this song. We do “this” at the sax solo, etcetera, etcetera. So, we would have all of these things written out and we would have to adjust it. So, as an example, on the right side, if the trumpet comes in and it’s not quite loud enough, and the bass is there too, well, you have an equalization there and you have a level control. So, on the right channel, as soon as that trumpet comes in, you roll off the bass, but turn up the level. So now the bass stays where it is, but the trumpet comes up. That’s a very simplified example, but that’s the kind of thing we were doing. We were trying to mix it on the spot because we wanted to keep that performance. And because of that I learned a lot about how to manipulate sound and more and more people wanted me to do that to their records.

Secrets Sponsor

So, after Contemporary, you moved to A&M?

Yes, I moved over there in late 1968 and eventually got to be Head of Mastering. On a bigger level, it also started the breakdown of union control in the recording industry. I wasn’t part of the union at Contemporary because we were too small, but A&M didn’t want to deal with all the union stuff so, along with me, they hired mixing staff away from the major studios by offering them much higher salaries.

So, at A&M I started mastering all of Sergio Mendez’s and Herb Alpert’s albums (except their first ones), the Carpenters, Earth Wind and Fire, Steely Dan, Michael Jackson. I was at A&M for 15 years and have worked on thousands of albums, some I can’t even remember.

I had a great time working there and they treated me well but after 15 years, things were getting big, overly corporate, and generally more difficult. So, I knew that I was ready to move on. And at that time, Allen Sides of Oceanway Studios (probably one of the definitive Hi-Fi bugs in the city) was coming to me to get mastering done. He talked to me about setting up a mastering department in his studio. So, we made a deal and set up all these plans to move over there.

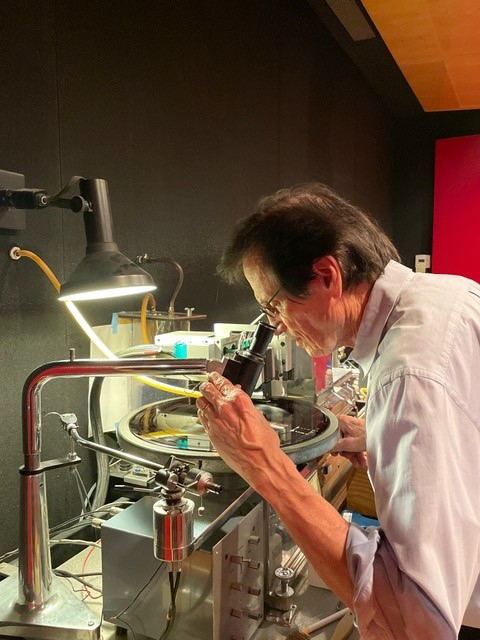

Bernie Grundman Mastering in Hollywood

Bernie Grundman Mastering in Hollywood

So that was the beginnings of Bernie Grundman Mastering?

Yes. That was the start. We now have 5 full mastering studios here in Hollywood and we have mastering studios in Tokyo, Japan.

Bernie Grundman at the board

Bernie Grundman at the board

You know it’s interesting how this all happened because I’m not, I’m not totally sold on myself. I know that it’s both man and machine. You have to have the tools to get you what you ideally would like out of something that you’re listening to. So, it’s a very big part of it, having the right equipment and tools and monitoring system and all that stuff. I saw plenty of other engineers that were doing fairly well, and when they would move to another mastering studio whether for better pay or something else and they’d fall flat because the equipment they had to work with wasn’t that good and the quality was poor, or they couldn’t do what they wanted to. So, because I always want to make sure we have the right tools, we have two full-time tech guys who custom-build all our equipment in the studios. You can’t buy any of the equipment we use. If we do have to buy a piece of gear, we take the time to “hot-rod” it with better power supplies, wiring, you name it.

Okay, so this is making the Audio-Nerd in me go bananas!

Bernie Grundman at the cutter

Bernie Grundman at the cutter

Oh, yeah! But that’s the driving force in what we do, the quality. I mean, that’s always, our main criteria, we want to at least have a system to where, when you go through the whole system, it’s almost impossible to hear the difference between the source and the result and then still be able to manipulate it. We want equipment there in the signal path that results in very little degradation. When we make a lacquer here, with our system, we have a calibration cartridge and everything on the same turntable as it’s being cut on, and we can listen to a half turn away exactly what was cut. Just to hear how they match up. We find it’s next to impossible to hear the difference on our system.

So, what do you use for a calibration cartridge? Is it something custom-made?

No. We use a Shure V15 moving magnet cartridge for calibration. I think it’s the very last version of the V15 that they produced. We calibrate it with and RCA test record that they first started pressing in 1949.

Really? A Shure V15.

BG: Yes, probably the best cartridge ever made. It measures incredibly flat, and it doesn’t require a lot of weight, so it tracks beautifully without tearing up the vinyl. We have a bunch of new original replacement stylus for whenever we might need to replace one. Needless to say, we’re very careful with these. It’s a shame Shure stopped making them.

How does it feel to come back “full circle” and remaster this music from Contemporary again for LP?

Well, it was fun to open up some of those tape boxes and see my old mastering notes on the master tapes! And the client basically came to me because they want what I think is going to work on these reissues, so I appreciate that. And, honestly, I think that some of the best sound ever was what we were able to get back then, as opposed to what we get now. On the Contemporary stuff, the simplicity and directness of the recordings captured some of the best sound of the time. Today we have so much flexibility and so many tracks to play with that the quality can suffer more in the end.

So, is the remastering for the Contemporary re-releases a completely analog process?

Yes. The Contemporary Records titles are the perfect candidates for a completely analog remastering process. They sent me the original master tapes and there really is very little that needs to be done to them and so it’s perfect for us to keep it all analog.

There are other situations when the original masters can’t be found or won’t be released and we’ll be sent either a digital copy to work from or a 1-to-1 analog transfer from the original master tape, which is the next best thing. And so, when you don’t have to go through these conversions, to take it back to analog and then cut it from that, after it’s been digitalized once, thats always better. If they send us a digital copy of the master and then we have to convert it back to analog, right away it’s not gonna sound as good. For example, when I remastered most of the 75 albums for Blue Note a while back, they wouldn’t let me cut the lacquers from the original tapes. They wanted to do this budget line, and they wanted it priced at $19.95 each or something like that. And I didn’t necessarily cut all of them, but I did all the digital transfers. So, they sent mostly analog copies of the masters, not the originals, and I did the digital transfers for their streaming and downloads, to 192 kHz and 96 kHz sampling rates. We even had a special computer that we put together ourselves for the job with our own special power supplies and other things. Now, just like at Contemporary, we tried to keep a very simple signal path. Rudy Van Gelder did a similar style of mixing that we did back in the day, but he panned stuff from left to right. So, we were trying to match the original Blue Note pressings that they had over at Capitol Records because they owned the label. But we wanted it to be better quality on these file copies. So, we would sort out the panning and then just use two bands of EQ, if we needed it, to try to get the sound the way we wanted it. We tried to do very simple transfers because usually those are fairly good sounding right off of the tape. They’re not as good as Contemporary, I mean, Blue Note never was (chuckles) but they did have some of the greatest jazz performances and talent on records.

But going back to analog and digital for a sec. The thing is, I had the analog tapes, the 1-to-1 copies (mostly) that I was working from. And I knew what they sounded like, because I was transferring them. But when I would compare them to the digital file copies we had on our computer that we made, it’s just not the same. No matter what we did, even at 192 kHz, the digital transfers had lost something.

What do you attribute that to?

BG: For me, what’s happening with digital is that, even at 192 kHz, it doesn’t sample the waveform finely enough. Something happens to the high end and the stuff that’s real short wavelengths. The extreme high end. That’s why I call digital a lot of times “skinny sound” because it’s not as wide on the top end. Low-level information doesn’t reproduce well with digital either. If you were just recording something digitally and you kept lowering the level into the digital machine that you’re recording on, the distortion would increase, increase, and increase until you’re way down. So, the stuff that actually adds a richness to a note from an instrument are the overtones and the resonances. And that’s why with acoustical instruments, digital has a really hard time in capturing all those little subtleties there, they tend to actually get lost. And that’s why sometimes digital actually sounds more detailed because you’re getting down to the primary frequency of the instrument. You’re not hearing those overtones and the size of it and the richness of it and the resonances.

Do you have a personal favorite of the Contemporary titles?

Well, I’ve always liked Art Pepper Meets the Rhythm Section. That’s always been one of the more impressive ones.

I have to ask, out of all the albums you’ve worked on, what is the absolute weirdest or most bizarre project you’ve been involved with?

Uh, well there was this guy who was trying to get back his popularity as a pop record producer. So, he came up with what he thought was this really, so-called, exotic music idea. It was literally just a tambourine band!

What?!

(Laughs) Yeah! I mean, he had all these tambourines that were playing together, and it turns out that’s the absolute worst thing to try to cut on a disc! (Laughing) Because of the RIAA curve, the frequencies that the tambourine has are demanding a lot of power from the cutting amplifier. Before we knew it, it ended up blowing out the cutter head and there was so much high end there that it burned out the coils.

Oh my God!

Yeah, it was crazy. I don’t know what the heck he was thinking. It sure didn’t sound musical!

Do you find that you are doing more mastering for vinyl now or whats the balance between vinyl and digital work?

BG: I’m doing a lot of vinyl now. But that’s only because I don’t want to personally take much pop stuff on anymore. I want to work only with all this archival stuff, the jazz stuff and the audiophile stuff because that’s really my basic roots, right? So, I’ll have my other engineers do the pop stuff. Their doing it all. One of them got nominated for the best album and best single of the year. Great! More power to him. Just so long as he works for me! (Laughs)

So, what sort of Hi-Fi system does Bernie Grundman listen to during his down time?

I currently have a vacuum tube playback system with a tube Marantz preamp and McIntosh tube amps (30 watts per channel) running a pair of big Tannoy Westminster speakers. Just like with recording, I like keeping the signal path as simple as possible and I’ve always found lower powered amps (when paired with efficient speakers) to sound better to me than higher powered ones.

So, if Bernie Grundman were stuck on a desert island what would your desert-island albums be?

Well, certainly Bartok’s Concerto for Orchestra by Fritz Reiner and the Chicago Symphony. I think it’s the most important piece of music of the 20th Century. When you listen to those five movements, it takes you on an incredible journey. Another album would be The Bridge by Sonny Rollins. That was a landmark album for him.

Bernie, thank you so much for your time. It was an absolute pleasure!

Likewise. Take care.