As an engineer myself, I can only speculate on the psychological motivations at play, so I enlisted the help of a bona fide psychologist to try and get to the bottom of this.

Audiophile Tweaking – Why?

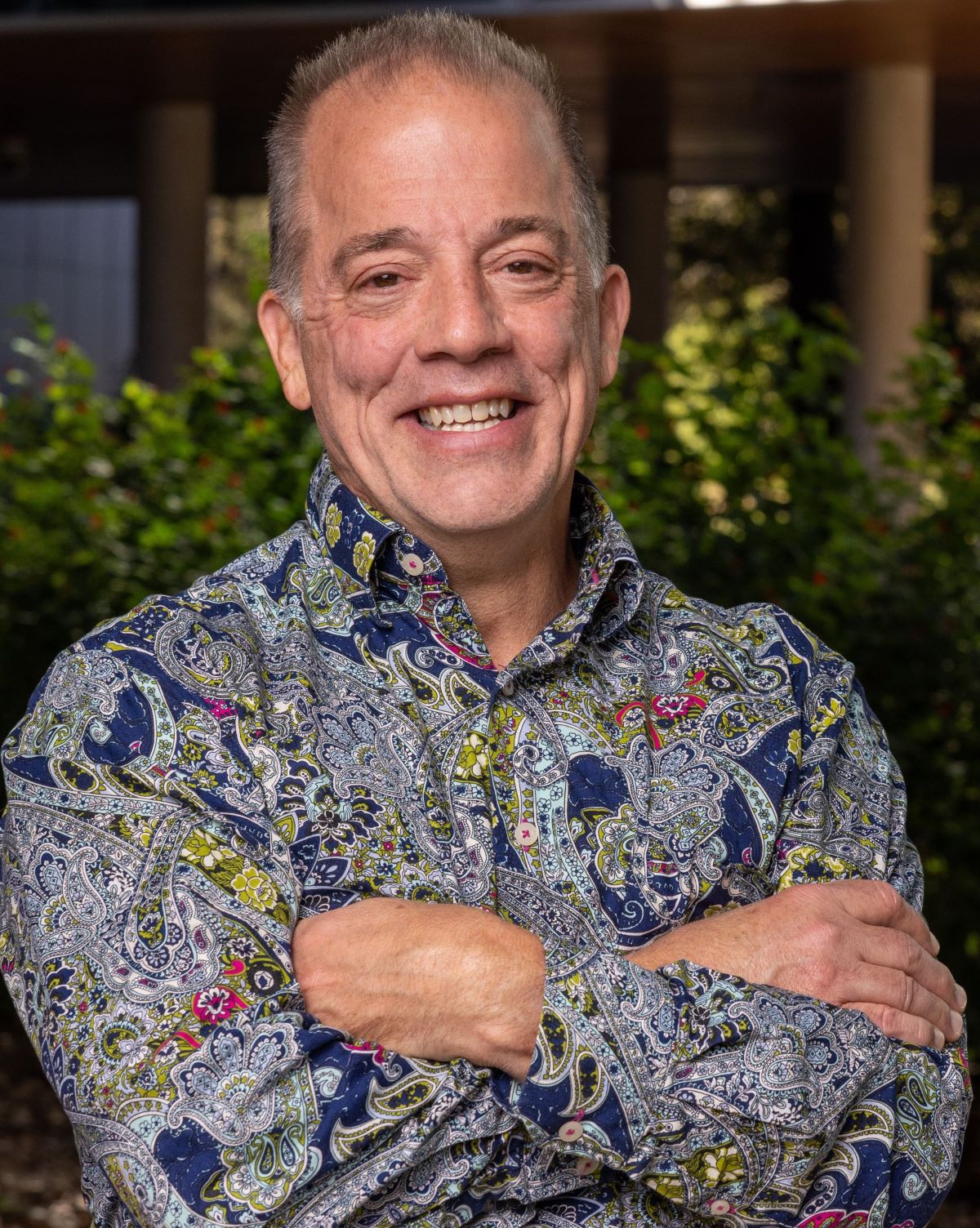

I recently set out to understand why audiophiles are so susceptible to believing that there are non-scientific explanations for ways to improve their enjoyment of their hobby. Instead of me simply spit-balling my own ideas, I decided to get help from a psychologist so I could understand a professional’s viewpoint on the topic. The psychologist who will provide his input on our conundrum is Dr. Donald R. Lucas, Ph.D., Professor of Psychology and the Coordinator of the Northwest Vista Psychology Department in San Antonio, Texas. This gentleman is affectionately referred to as “Dr. Don” by his students.

I have only gotten a cursory introduction from Dr. Don as I write this little preamble. I mention this because his initial thoughts literally forced me to rethink how I was going to approach this article, because Dr. Don and I are coming at this from two different perspectives; I am a lifelong audiophile, and Dr. Don is not. As a result, we have wildly different perspectives on this topic.

I was originally going to put together an outline and then fill out the narrative, folding in feedback from Dr. Don. But now, I think I will instead give you my perspective first and then follow that with a section that will flesh out Dr. Don’s understanding of the topic. Before we begin, I must at least discuss one initial thought he had that changed my whole approach!

I wanted to title this editorial, “Exploring the Roots of Audiophilia Nervosa,” because “audiophilia nervosa” is what this phenomenon has always been called my entire life. Whoever coined that phrase has long been forgotten. In any event, Dr. Don quickly took umbrage concerning that nomenclature.

Here is what he has to say about that:

Specifically, what you describe in the article thus far can best be explained by an addiction of some sort. Note, addictions are psychophysical—they have physical components (the peripheral and central nervous systems are involved, i.e., nerves) and psychical components (feelings and thoughts are involved, i.e., psyche).”

Well, things are starting off with a bang already!

Getting back to the main thrust of the article, I have decided to split this editorial into two main sections: Audiophile Tweaking, an Audiophile’s Perspective, followed by Audiophile Tweaking, a Psychologist’s Perspective. I will then wrap up with my own conclusion to try and summarize what the heck I just put in front of you!

Audiophile Tweaking, an Audiophile’s Perspective: Jim Clements

It’s no secret that many audiophiles find themselves in a lifelong pursuit to improve the performance of their systems. This improvement mindset is realized in many different forms:

2) Obsessive work to optimize their listening spaces.

b) Improvements to their room acoustics, such as diffusers and bass traps.

4) Having their ears professionally cleaned from time to time.

I get all the above, as these are things that can have a scientific basis for how they impact and improve the musical performance of their systems. But there is another side to all this: other tweaks that have no real logical, objective, or scientific explanation.

Some may say these products are “snake oil,” while others may embrace these different tweaks by saying that science can’t explain everything, and they have a subjective impression that these other product categories do indeed improve the sound they are hearing.

The product categories I am referencing are numerous:

b) Power conditioners

c) Upgraded in-line fuses

d) Proprietary grounding blocks

4) Special isolation products (to reduce component vibration)

b) Ethernet switches

I could go on, but you get the idea. There is a whole industry out there that caters to the obsessive audiophile. Virtually none of the manufacturers of these products have bothered to perform or publish double-blind listening tests of their products.

All of the above is where the phrase “audiophilia nervosa” originated. This editorial is not here to debunk any of these products or to engage or incite another debate about them. If you like them and want them, good for you. My main quest here is to figure out why this obsession appears to affect audiophiles more than other hobbies.

What I mean is that I was sitting around and thinking about all this stuff one day, and it struck me that there are many videophiles out there, too. They want to improve their video experience to reach for that “looking out of a window” experience. But have you ever heard a videophile say that they upgraded the power cord to their display and now they have blacker blacks and less video noise? I personally have not, and that’s what got me thinking; there has to be some psychological explanation as to why these obsessions appear to be an audiophile phenomenon.

So, let’s dive a little deeper, shall we?

Human “audio memory” is short-lived. That’s why Harman has a carousel they use to switch out speakers in a split second as part of their blind listening tests that they use to update and refine their speaker designs. That’s because too much time passes if you manually change out the speakers, so they developed a cool device to make the switch before your ears forget what they just heard.

By the way, Harman uses double-blind testing to refine their products, hence their development of special waveguides and improved crossover topology, among other technological advancements.

Getting back to audio memory, there are lots of examples of people pitching audiophile upgrades and taking advantage of this fact to obfuscate their customers’ impression of any possible “improvements.” What I am driving at is, I have been in demos where they pause the music, make a change, and then restart the music. This means that your audio memory has faded before the music plays again, making it more difficult to assess any “improvement.” Then the salesman will confidently react to the amazing sound now that whatever product they are pitching is introduced to the system. If you didn’t hear the improvement, then there must be something wrong with your ears or you.

One day, I asked Steve Guttenberg about his thoughts on the topic, and one of his ideas was also related to audio memory. One idea he shared involved my comparison between videophiles and audiophiles. In the video realm, you can see two displays side-by-side while demoing. You can’t do this in audio. So, again, this simple fact complicates our ability to differentiate clearly between two different audio setups or products.

I have also concluded that audiophiles tend to be susceptible to conformity bias. I have fallen for this. This is how it usually goes: you are confronted by a cool and confident salesman, who will look you in the eye at the end of the demo and say something to the effect of, “Wow, isn’t that much improved?” Of course, you are baited into agreeing with them because they are cool and confident.

Their leading queries make it harder to say you didn’t really hear anything, which leads to a sense of personal insecurity. Many audiophiles may be uncertain about their own hearing acuity and wouldn’t want to tell the cool salesman that they didn’t hear a difference. If they did, ridicule may ensue.

I think audiophiles, more than other hobbyists, obsess that their system isn’t perfect (none are), but they are constantly trying to pinpoint new areas of imperfection to work on. This is actually kind of sad, to be honest, and is part of the idea that audiophiles use music to listen to their systems and not the other way around. You can get a ton of enjoyment from an imperfect system. (Waxing philosophically, something to keep in mind as you read further, if there is no such thing as a perfect system, then there is no such thing as an imperfect system either.)

Many audiophiles, for whatever reason, feel that there is some cause and effect in the audio reproduction chain that can’t be explained through scientific methods. So, they balk at objective measurements and other engineer-inspired metrics. They can even get so caught up in this idea that they wind up being put off by any sort of measurement- related claims. Are their tweaks somehow “magic?”

Why not use double-blind testing to validate tweaks? Double-blind testing is very common in virtually every other industry. In this type of testing, listeners are asked to compare three samples, two are the same and one is different. The first test is, “Can they reliably determine which is the different one?” If they can make this selection at a statistically relevant frequency, then the next question is, “Which do you prefer and why?”

Few companies that sell tweaks validate their products’ efficacy through double-blind testing. Are the makers of these products afraid that people can’t actually hear the difference? What other reasons do they have to avoid this testing? It would be part of a rigorous product development and improvement program in almost every other industry.

Finally, I know of at least one manufacturer of audio tweak gear who claims that he has identified a heretofore untapped class of products that doesn’t follow conventional physics, and their products are based on an understanding of physics that nobody else is doing. I asked why they didn’t have patents, and they said they didn’t need patents on the system, just on the individual components. This still baffles me. Why would you pioneer new technologies and not protect them by way of a patent? I have my thoughts on this, and they will remain private for the time being.

Audiophile Tweaking, a Psychologist’s Perspective: Dr. Donald R. Lucas, Ph.D.

Thank you, Jim, for your thoughts on this matter from an Audiophile’s Perspective. And thank you for introducing me. Indeed, I am a psychologist with my Ph.D. training in neuroscience and behavior. And, indeed, I am not an audiophile per se. However, I have dabbled in being an audiophile. During my adolescence and young-adult years, I designed and built lots of speaker cabinets, including a set of folded horn cabinets not too unlike a set of Klipschorn’s La Scala AL5 speakers; that, of course, as a college and graduate student, I could have never afforded, and of course, as a psychologist, I still today cannot afford. 😊

Enough about me. Let’s get to the problem at hand—or, for that matter, the problem at ear: Answering the question, why audiophiles are so susceptible to believing there are non-scientific explanations for ways to improve their enjoyment of their hobby.

The answer to this question is in part in the audiophile’s three basic demographics:

Socially and economically speaking, audiophiles tend to come from upper-middle to high-class backgrounds.

Not having a lot of money lends itself to being rational: “What bills must I pay before tweaking my audio system?” Whereas, having lots of money, lends itself to being irrational: “How can I be satisfied with my audio system when I know I can afford a more expensive system?” Audiophiles who have “not gone over the edge” recognize how much money they can afford to spend on an audio system, whereas audiophiles who have “gone over the edge” follow marketing and advertising.

When it comes to age, audiophiles are older.

All five senses—sight, hearing, smell, taste, and touch—deteriorate in irreversible ways with age, but hearing is the most significantly affected with progressive and permanent hearing loss affecting frequencies above 8,000 Hz in young adulthood and steadily worsening, moving down the frequency range. We are born with the ability to hear frequencies between 20 and 20,000 Hz, but by the time we are 20 years of age, we will not have the ability to hear frequencies above 18,000 Hz, by the time we are 40 years of age, we will not have the ability to hear frequencies above 15,000 Hz, by the time we are 50 years of age, we will not have the ability to hear frequencies above 12,000 Hz, and by the time we are 70 years of age, we will not have the ability to hear frequencies above 10,000 Hz. Audiophiles who have “not gone over the edge” accept what their auditory sensory systems are capable of hearing, whereas audiophiles who have “gone over the edge” deny what is neurologically possible with their hearing.

Audiophiles are overwhelmingly male.

Men are considered more likely to be susceptible to the optimistic bias. The optimistic bias is the tendency of an individual to overestimate the likelihood of positive events happening to them and underestimate negative events happening to them, especially when the individual is partaking in risky behaviors. “I know there are a lot of expensive and unproven products claiming to significantly improve audio systems, but I will not be fooled by any of them because (fill in with any irrational explanation here).” Audiophiles who have “not gone over the edge” seek double-blind scientific comparisons relative to their audio systems; whereas audiophiles who have “gone over the edge” ignore scientific logic and data when it comes to their own audio systems.

As Jim mentioned, the words “audiophile nervosa” are typically used to label the audiophile who has “gone over the edge.” “Nervosa,” being only about nerves, does not adequately label the audiophile who has “gone over the edge.” In addition to nerves, the audiophile’s psyche must be included to address how irrational this condition is.

For example, an audiophile tweaking their audio system is rational. Tweaking is normal. Tweaking is making changes to an audio system to make the system sound better. However, audiophiles who have “gone over the edge” make changes to their audio systems, but their systems do not rationally sound better; instead, their systems irrationally sound better.

An audio system “irrationally sounding better” is probably best described in a bit titled, “Googlephonics,” by Steve Martin, on his album, Comedy is not Pretty. 🙂

To put it plainly, this is not normal.

If I were to create an explanatory label for audiophiles who have “gone over the edge”— that incorporates the audiophile’s nerves and psyche, I would label them as having Audiophilia Addiction (AA). AA involves a person gaining pleasure from the listening experience, but the person relatively quickly adapts to the physical audio components, allowing for this pleasurable listening experience. This adaptation no longer allows pleasure. Thus, AA leads the person to need to change the physical audio components until the pleasure returns relatively quickly, then they adapt to these new physical audio components, allowing for this listening experience. This vicious cycle of pleasure, adaptation, loss of pleasure, and changing physical audio components continues until eventually there are no “rational” changes the person can make to the physical components of their audio system to make the listening experience pleasurable. So now, from the outside looking in, one would see this person adding to their physical audio system bizarre/irrational/non-scientific components to make it sound “better.” Note: sadly, but psychophysically true, the pleasure originally experienced from the original physical audio components was, in fact, the best pleasure they ever had from listening to music.

AA is not only caused by the psychological characteristics associated with the audiophile’s demographics. The environment also plays a significant role in causing AA. With the environment being marketers and advertisers. Affluent, older men are heavily targeted by fraudsters and deceptive marketers, and advertisers. The combination of wealth, life-stage vulnerabilities, and the male ego makes audiophiles attractive marks for those with malicious intent. Without conscience or recognition of addiction’s consequences, these marketers and advertisers will sell the audiophile tin foil at $3,000 a roll if they can get the audiophile “to believe” their system sounds better.

And do not think the audiophile who has “gone over the edge” is unique in this circumstance. The same “cool and confident” salesman-type dealing proprietary grounding blocks is also dealing UHD, fashion, craft beer, online sports betting, ultra- processed foods, and BlueChew—all for YOU to have: the perfect audio system, the perfect video system, the perfect look, the perfect high, the perfect win, the perfect health, and the perfect orgasm.

Well, that just about wraps up our discussion regarding Audiophile Addiction. It sure sounds like a somewhat bleak picture for audiophiles who have “gone over the edge”. However, I hope that our editorial may in some way help other audiophiles accept that their senses will diminish over their lifetimes and that they will try to find a way to return to their seminal feeling of satisfaction they had in their younger days. Just remember that there are people out there who want to take advantage of you by selling you unproven products that do little except perhaps fuel further purchases of questionable products.

We will be working on a follow-up editorial where we will dive into ways for the audiophile to derive maximum pleasure from their systems without feeling the need to go over the edge.

Biography:

Dr. Don Lucas, Ph.D., is a professor of psychology and the coordinator of the psychology department at Northwest Vista College in San Antonio, Texas. He is a fellow of the Southwestern Psychological Association and the Association for Psychological Science.

His teaching has been featured by The San Antonio Express News, SA Scene Magazine, KENS5 CBS, and KSAT12 ABC; his teaching has earned him several awards, including the Minnie Stevens Piper Award, the oldest and most prestigious teaching award for higher education in the state of Texas.

Dr. Lucas is the author of the book, Being: Your Happiness, Pleasure, and Contentment, and the author of the teaching modules, The Psychology of Human Sexuality and Human Sexual Anatomy and Physiology, published on nobaproject.com. He hosts 5MIweekly, a virtual science-based sex education course on YouTube, composed of original and pedagogically interactive videos. 5MIweekly has over a million views and thousands of subscribers.

His latest scientific research on happiness and sexuality can be found on his two Medium channels: @Wonderments and Human Sexuality.