In reviewing the Revox B77 MK III Analog Tape Deck (shown below), the Revox factory sent me three additional tapes that are studio master copies. I decided to put those reviews in one of our “What We Are Listening To” articles. There are links to the Revox/Horch House website giving more details about each album and its cost. All of the tapes reviewed below were recorded on ¼” RTM SM 900 tape, two-track stereo, at 15 IPS, CCIR EQ, and 510 nWb/m.

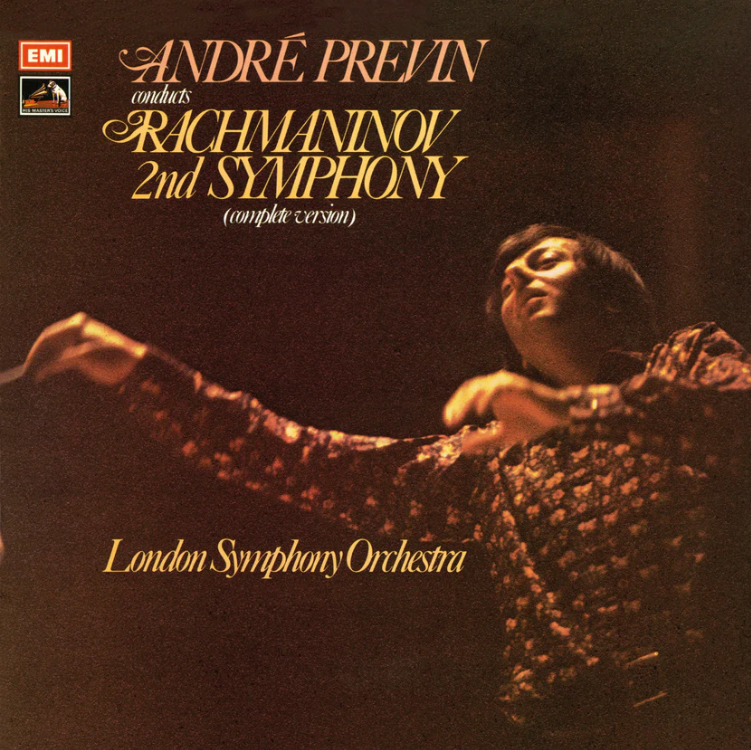

Rachmaninov 2nd Symphony, Andre Prévin, London Symphony Orchestra, EMI, 1974.

Analog tape is so different from digital recordings. This is not nostalgia speaking; it is physics, execution, and preservation converging in a way that modern digital often struggles to replicate emotionally, even when it excels technically.

The continuous voltage waveform preserved on tape conveys musical motion without the discontinuities inherent in digitally sampled systems. Rather than reconstructing sine waves from discrete points and suppressing the resulting artifacts, the analog signal flows naturally, producing a smoothness and coherence that is immediately audible. Through the B77 MK III, that continuity translates into an effortless presentation, free of edge or glare, with a natural decay that feels unforced and organic.

In this recording, the first movement unfolds patiently, establishing Rachmaninov’s expansive thematic landscape with remarkable clarity. The second and third movements feel almost narcotic, lush, inward, and gently hypnotic, while the fourth movement arrives like a physical awakening, its dynamic contrasts rendered with authority but never strain. What stands out most is the string tone: the violins have a tactile quality, like fingers gliding across the finest silk, supple yet precise.

Perhaps most astonishing is the transparency of the recording itself. For a 50-year-old master, the absence of haze, congestion, or loss of detail is extraordinary. Played on the Revox B77 MK III, this tape doesn’t merely reproduce music; it recreates a living, breathing performance in real space.

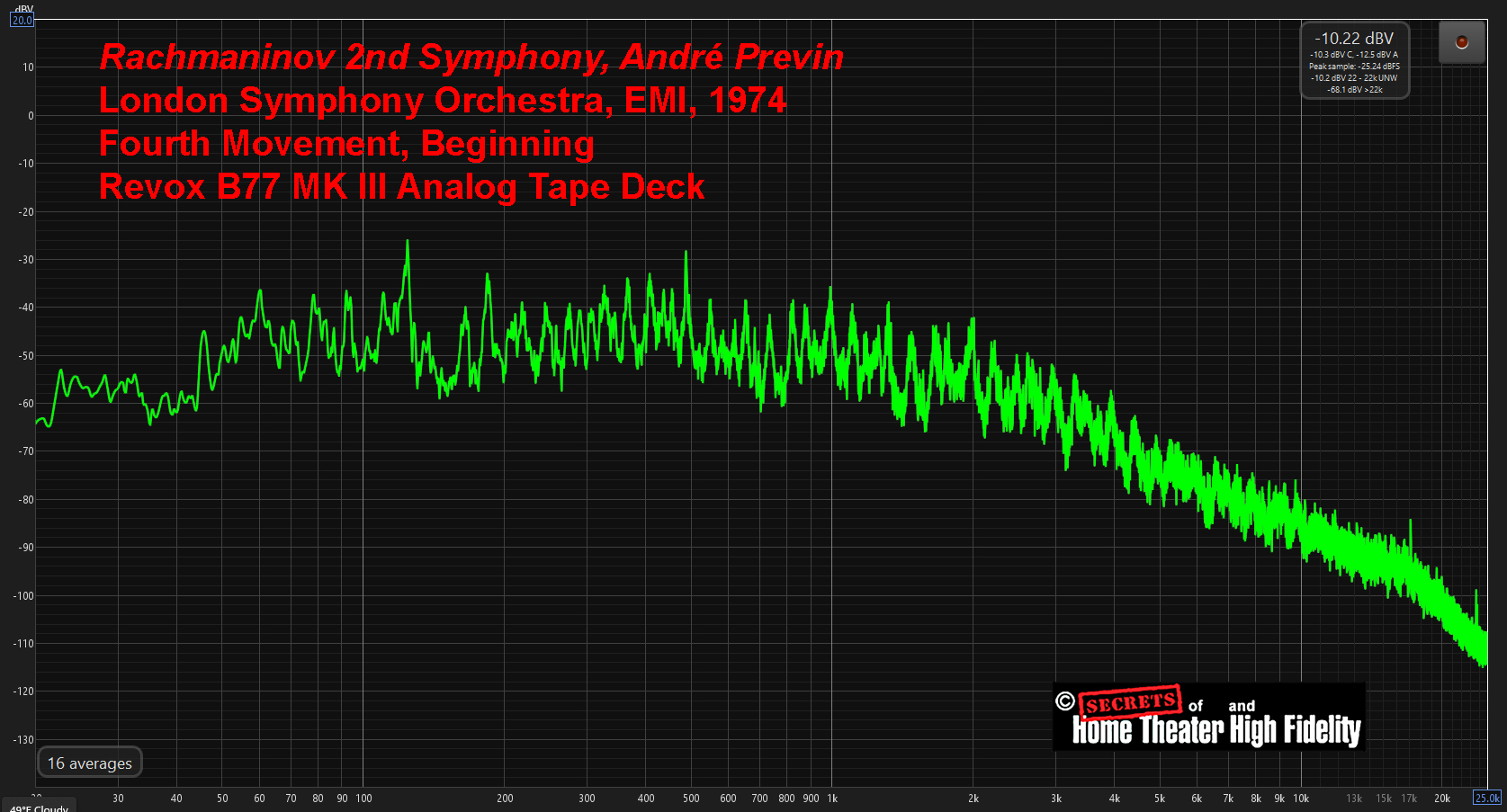

Here is a spectrum analysis of the first 30 seconds of the fourth movement. It shows content out to 25 kHz.

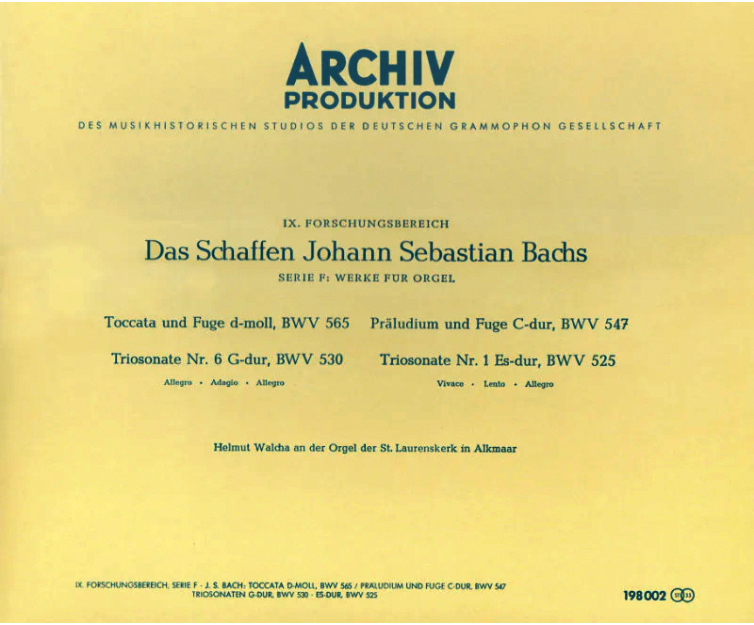

The Works of Johann Sebastian Bach, Helmut Walcha, Organ of the St. Laurenskerk in Alkmaar, Archiv Produktion, 1959.

https://www.horchhouse.com/en-us/products/johann-sebastian-bach-organ-works?variant=56079799648591

I was very interested in listening to this album because, 1., it is 67 years old, and 2., I wanted to hear what the B77 did for deep bass. Well, I was not disappointed. The well-known “Toccata and Fugue in D Minor” sounded terrific. And, it wasn’t just the deep bass. Every note is clearly distinct, with an organic (pun intended) presence that is just undeniable.

Hearing The Works of Johann Sebastian Bach, performed by Helmut Walcha on the organ of the St. Laurenskerk, via a master analog tape played on the Revox B77 MK III, is a humbling reminder of just how beautiful early analog recording could be when executed with care.

Recorded in 1959 by Archiv Produktion, this tape is now 67 years old, yet it sounds anything but antiquated.

Pipe organ recordings live or die by their ability to convey low-frequency weight without turning to mud, and here the B77 MK III delivers magnificently. The opening “Toccata and Fugue in D Minor” is thrilling, not merely for its subterranean power, but for the way that power is shaped and controlled. The pedal notes have mass and authority, yet remain fully resolved, never obscuring the harmonic structure above.

What truly impressed me was the clarity across the entire spectrum. Every line, manuals and pedals alike, remains distinctly articulated, with an organic (and entirely appropriate) presence that digital often sterilizes. The “Prelude and Fugue in C Major” displays remarkable contrapuntal separation, while the “Trio Sonatas (No. 6 in G Major and No. 1 in E-flat Major)” reveal rhythmic agility and tonal purity that feel startlingly immediate.

The Revox B77 MK III excels here not by editorializing, but by getting out of the way. It preserves the continuous voltage flow of the original recording, allowing the church acoustics, the instrument’s breath, and Bach’s architecture to unfold naturally. This is analog tape at its most convincing and most musical.

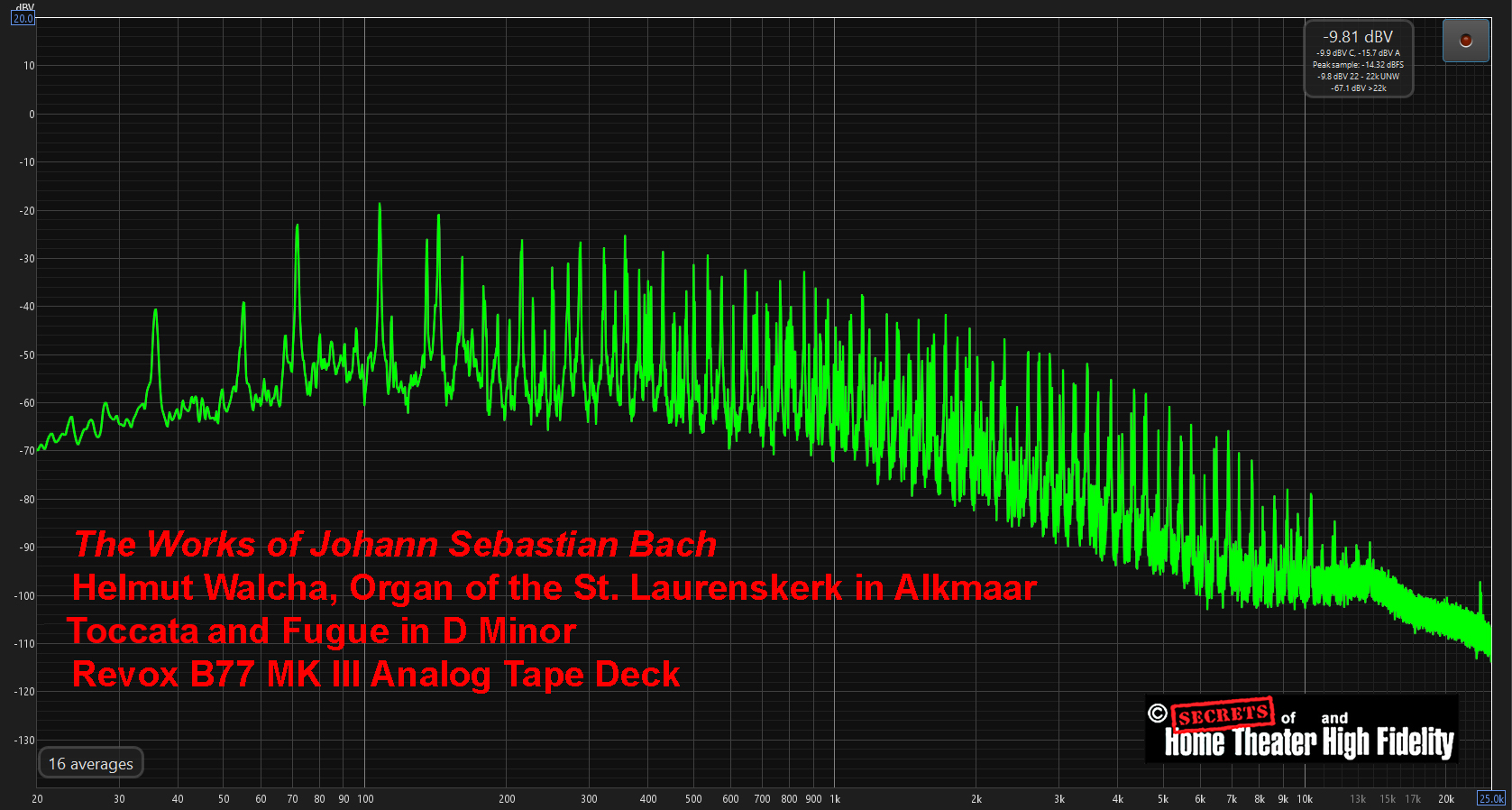

Here is a spectrum from the opening 30 seconds of the “Toccata and Fugue in D Minor”. Note that the peaks have a bit of space in between them. This is because we are dealing with a single instrument being played. There are many peaks because the musician is playing many notes at the same time with ten fingers on the keys and two feet on the pedals.

Violin Concerto in D Major, Opus 35, Serenade Melancolique, Opus 26, Itzhak Perlman, Violin, Eugene Ormandy, The Philadelphia Orchestra, Warner Classics, 1979.

This album is 47 years old. Again, however, the recording sounds as if it were recorded yesterday. The concerto in three movements, compared to a symphony, which has four, was released as a premiere in 1881 with a bad review, partly because it was so difficult to play, perhaps just because that fact would hurt the ego of the top violinists of that time.

In any case, it finally came to be considered one of the most popular of Tchaikovsky’s concertos. Perlman played it at his first concert in 1964, and played it again and again at subsequent concerts. He is such a superb violinist, I suspect it sounded just the same at each one. Astonishing.

This album lifts as well as calms the soul. The B77 reproduced it beautifully, each note of Perlman’s violin reaching beyond the orchestra to draw the listener in and keep them there. I continue to be amazed at how different classic analog sounds from digital recordings. Analog has more distortion for sure; this is responsible, in part, for the sound quality.

Tchaikovsky’s Serenade mélancolique, Op. 26, is widely regarded as a melancholy, introspective work, though it’s a refined and lyrical melancholy rather than overt despair.

The piece unfolds in a slow, elegiac arc, with the solo violin singing long, plaintive lines that feel inward-looking and reflective. This is classic Tchaikovsky: emotional intensity held under formal control. The sadness is restrained, almost noble, closer to nostalgia and quiet longing than anguish.

Composed in 1875, this piece sits squarely in Tchaikovsky’s emotionally vulnerable period. He himself used the word mélancolique, which in the 19th-century Romantic sense implies poetic sadness, not depression.

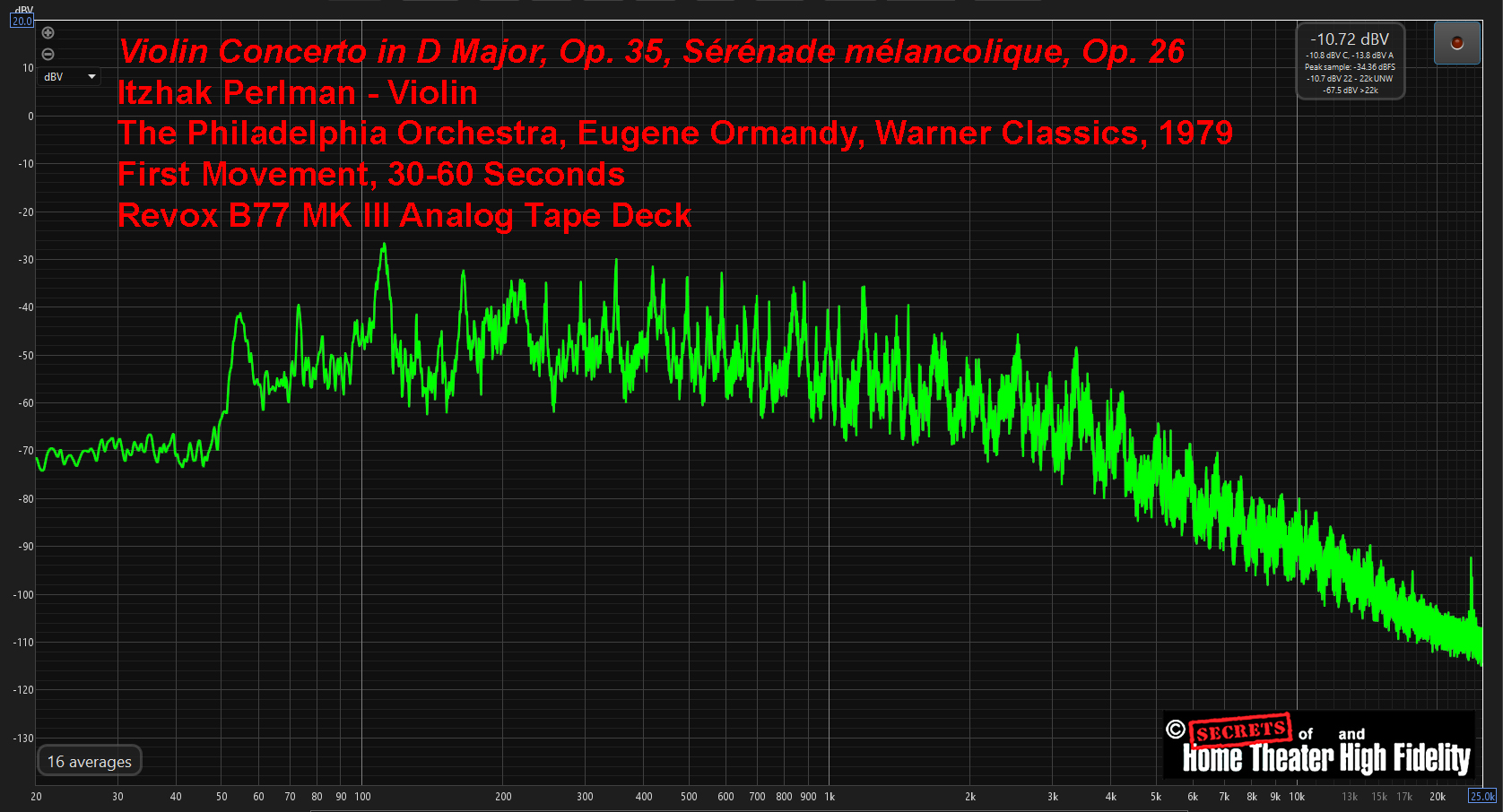

Here is a spectrum of 30 seconds near the beginning of the first movement of the concerto. There is a nice spread of frequencies out to 25 kHz.