Newly designed recording and playback electronics are one of the most notable aspects of the B77 MK III. Revox claims that the manufacturing and quality control steps are so stringent that they can only produce 20 decks per month.

Revox B77 MK III Analog RTR Tape Deck

- Small playback head gap (0.25μ)

- Newly designed electronics

- Two headphone jacks

- Film capacitors instead of electrolytics

The new B77 MKIII deck is not simply a refurbished MK II. It has been completely redesigned and re-engineered, incorporating several updates and revisions over previous generations. These include new tape head designs, with the playback head now having only a 0.25-micron gap, maximizing high-frequency resolution. Typical gaps for tape decks in the past were about 2 microns, so this head is smaller by a factor of 8. That makes a significant difference in the quality of the recording. Just to show you how small that gap is, the average human hair is 70 microns in diameter. How Revox manufactures a gap of 0.25 microns must be an engineering feat.

MSRP:

$18,995

Website:

Company:

SECRETS Tags:

Revox, B77 MKIII, Analog, RTR, tape deck, reel-to-reel tape decks

Secrets Sponsor

First of all, analog tape works through a principle called magnetic flux, which is a feature of electromagnetism, one of the four basic forces in the universe.

Magnetic tape flux density indicates the level of magnetization recorded on the tape, measured as magnetic flux per unit track width. The standard unit is nanoWebers per meter (nWb/m), where a Weber is the SI unit of magnetic flux.

SI stands for Système International d’Unités, the International System of Units. It’s the modern metric system, established in 1960 and maintained by the International Bureau of Weights and Measures in France. It defines the seven base units (meter, kilogram, second, ampere, kelvin, mole, candela) from which all other units are derived.

The Weber, named after German physicist Wilhelm Eduard Weber, is the SI derived unit for magnetic flux. One Weber equals one volt-second, or equivalently, one kilogram-meter-squared per second-squared per ampere. In tape recordings’ nanoWebers per meter, it expresses flux per unit track width, which gives you a way to compare magnetization levels independent of how wide the tape or track happens to be.

Reference Fluxivity

When we talk about “flux density settings,” we’re really discussing reference fluxivity, the magnetic flux level that corresponds to 0 VU or some other designated reference point on the meters. Common standards include:

● 185 nWb/m — The original NAB (National Association of Broadcasters) standard, common in the US for professional work.

● 250 nWb/m — A European DIN standard, also adopted by some US facilities.

● 320 nWb/m — An “elevated level” standard that became popular with improved tape formulations in the 1970s–80s.

● 355 nWb/m — Used by some facilities pushing hot levels on modern high-output tapes.

● 510 nWb/m — The EBU (European Broadcasting Union) standard for high-output professional tapes such as Ampex 456 and BASF 900, offering improved signal-to-noise ratio.

The choice among these standards affects where your 0 VU sits relative to tape saturation. Higher reference fluxivity means you’re recording a hotter signal at the nominal level, which improves signal-to-noise ratio but reduces headroom before saturation.

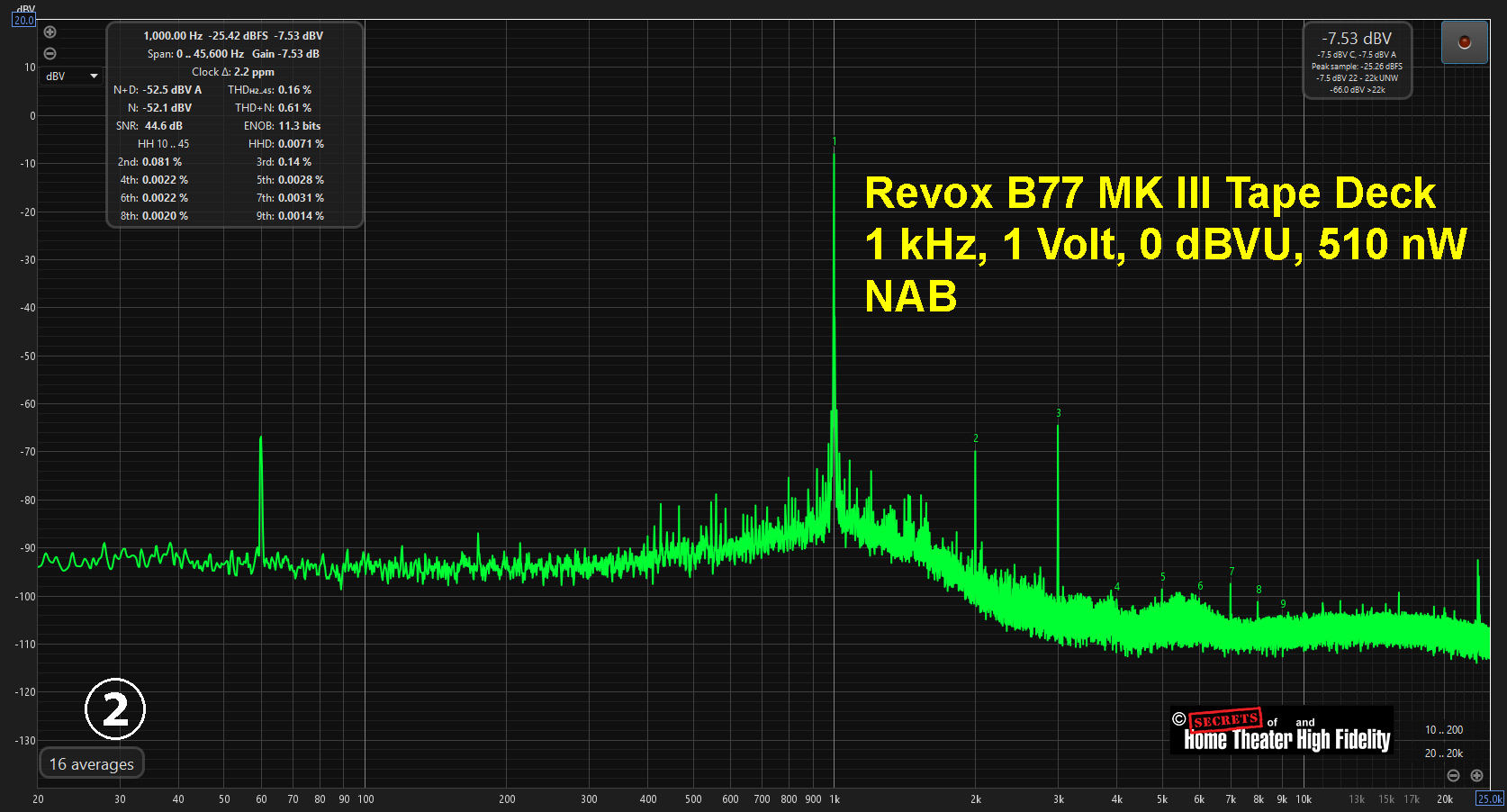

The Revox B77 MK III has two choices for flux settings, 320 nWb/m and 510 nWb/m. The difference relates to tape formulation and when the standards were established.

320 nWb/m is the older, more conservative reference level associated with standard ferric oxide tapes from the 1960s and earlier. It was the original NAB (National Association of Broadcasters) standard and remains common for archival work and older tape stock. At this level, standard oxide tapes operate comfortably below saturation with good headroom.

510 nWb/m (sometimes rounded to 500 nWb/m) became the standard for high-output professional tapes developed from the 1970s onward, formulations like Ampex 456, Quantegy GP9, and BASF 900. A modern tape suitable for this standard is RTM S900, which is what I use. These tapes use improved oxide particles, often cobalt-doped or with enhanced coatings, allowing them to accept more magnetization before saturating. The European broadcast standard (EBU) adopted this higher level. Recording at 510 nWb/m on these tapes yields a better signal-to-noise ratio since you’re putting more signal on the tape while the noise floor remains relatively constant. Even though RTM S900 is designed for use with high flux settings, I prefer 320 nWb/m because distortion is lower.

Using 510 nWb/m on an older standard-output tape would push it toward saturation, increasing distortion and compression—the tape simply can’t hold that much magnetization cleanly. Conversely, recording at 320 nWb/m on a high-output tape wastes its capability, leaving potential signal-to-noise improvement on the table.

This is why calibration matters: a tape deck’s meters, bias, and levels should be set for the specific tape formulation you’re using, aligned to whichever reference fluxivity matches that tape’s design parameters.

The tape heads in the B77 MK III are a new design, with the playback head having a gap of 0.25 microns (0.25μ). Older decks usually clock in around 2μ.

Here is a photo of the head stack. From left to right are the erase head, record head, and the playback head.

A smaller playback head gap extends high-frequency response. The relationship is direct: as the recorded wavelength on tape approaches the gap width, output falls off, reaching complete cancellation (the “gap null”) when wavelength equals gap width.

At 0.25 microns, your B77’s playback head pushes that limit far beyond audible frequencies. To put it in perspective, at 15 IPS, a 20 kHz signal has a wavelength of about 19 microns or roughly 76 times wider than the gap. Even at 3.75 IPS, where that same 20 kHz signal shrinks to about 4.8 microns, you’re still well clear of the gap dimension.

The practical benefits of that tiny gap include:

Extended treble response — The high-frequency rolloff begins gently well before the null, so a narrower gap delays the onset of losses, maintaining output further into the upper octaves.

Better performance at slow speeds — Since slower tape speeds produce shorter wavelengths, a narrow gap becomes increasingly important. A deck meant to perform well at 3.75 IPS needs a tighter gap than one used only at 15 IPS.

Improved transient resolution — Short wavelengths correspond to fast signal changes. A narrow gap reads these rapid transitions more accurately, preserving attack and detail.

The tradeoff is manufacturing precision and durability; maintaining a 0.25 micron gap requires exceptional tolerances and careful handling. It’s one reason the B77 MK III commands the price it does.

The frequency rolloff begins well before the wavelength equals the gap; it’s a gradual process that follows a mathematical function called the sinc function: Loss = sin(πd/λ) / (πd/λ), where d is the gap width, and λ is the recorded wavelength on tape.

The response starts tapering gently as the wavelength decreases toward the gap dimension. By the time the wavelength is about twice the gap width, you’re already down around 4 dB. The loss accelerates as you approach the null, and when wavelength finally equals gap width, you hit complete cancellation, the first “gap null” where output drops to zero (theoretically, at least; in practice, it’s just very deep).

If you kept going to even shorter wavelengths, the response would actually recover somewhat before dropping to another null when wavelength equals half the gap, then recover again, and so on, the classic sinc function ripple pattern. But in practical tape recording, you never operate anywhere near these regions; the first null is already far beyond the audio band for any reasonable head design.

So, the B77 MK III, with its 0.25-micron playback gap, experiences a gentle, progressive treble rolloff that begins subtly in the upper kilohertz range and would reach its first null at a wavelength of 0.25 microns, corresponding to frequencies in the megahertz range at typical tape speeds. The audible high-frequency losses actually encountered come mostly from other factors: spacing losses, oxide thickness effects, and the practical limits of bias optimization.

The record head gap is wider, typically 2 – 5 microns, compared to the playback head’s fraction of a micron. The physics of recording versus playback explains why.

During playback, the head must resolve the magnetic pattern already on the tape. A narrow gap acts like a fine aperture, allowing it to distinguish short wavelengths without averaging them together. Gap width directly limits high-frequency response.

During recording, what matters is the magnetic transition that forms as the tape leaves the trailing edge of the gap. The head’s job is to magnetize the tape strongly enough to overcome its coercivity, and the recorded signal is essentially “frozen” at that trailing edge where the field drops off sharply. The gap width affects how deeply the field penetrates the oxide and how efficiently the head drives the tape to saturation, but it doesn’t limit the shortness of the wavelengths you can record; that’s determined by the sharpness of the trailing edge transition.

A wider record head gap offers several practical advantages: stronger magnetic field for reliable magnetization, better efficiency (less drive current needed), more mechanical durability, and easier manufacturing tolerances. Since it doesn’t penalize high-frequency recording the way it would penalize playback, there’s no reason to make it as narrow.

This is fundamentally why three-head decks outperform two-head designs; each head can be optimized for its specific function rather than compromising between conflicting requirements.

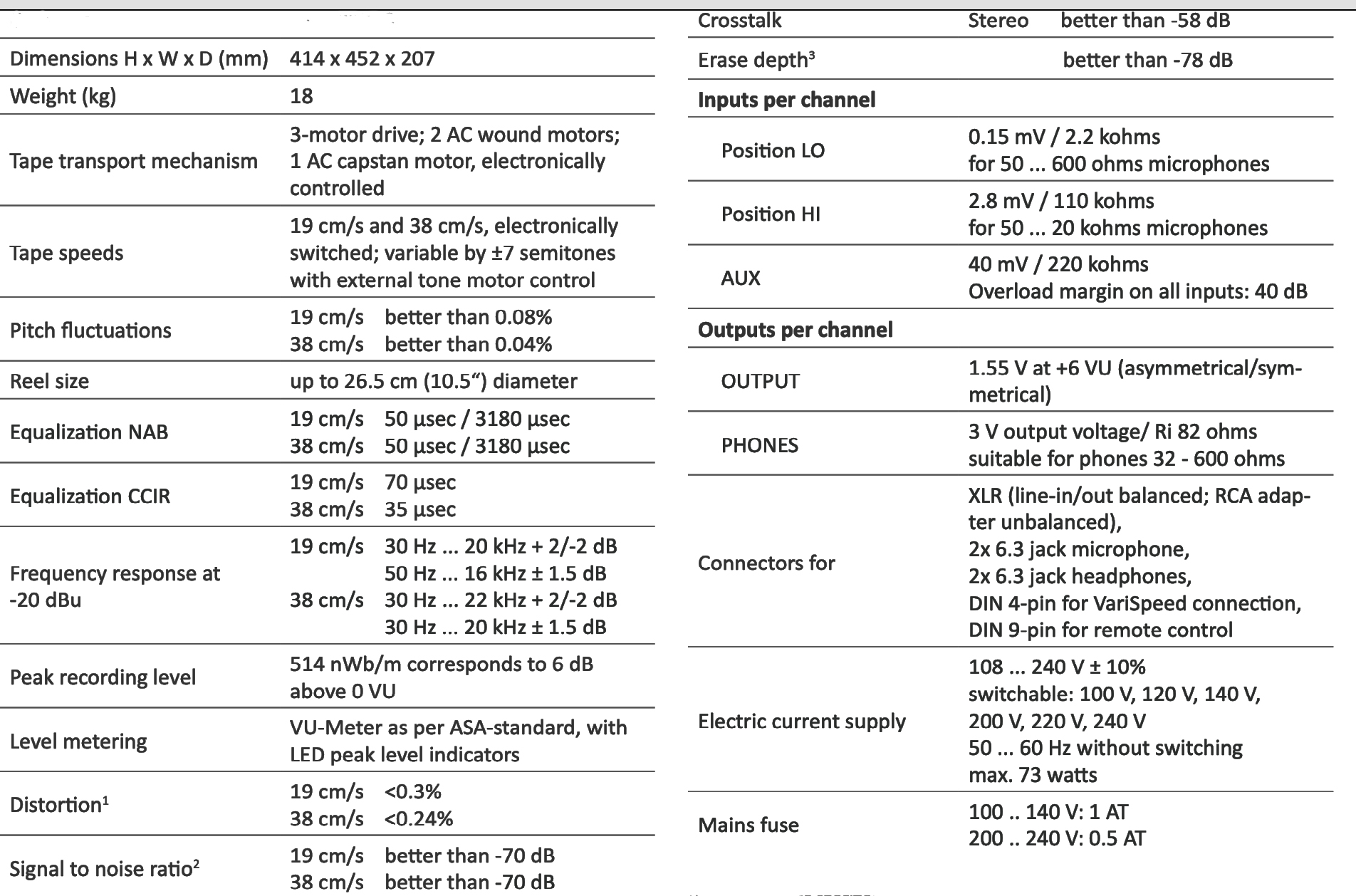

There are two equalization standards to choose from with the B77 MK III, CCIR (IEC), and NAB.

CCIR (Comité Consultatif International pour la Radio) equalization is essentially the same as IEC 1 (International Electrotechnical Commission), both referring to the European standard for tape bias/EQ, differing from the American NAB (National Association of Broadcasters) standard, with CCIR/IEC 1 generally better suited for modern tapes than NAB. A pre-emphasis curve is applied during the recording process, and a post-emphasis curve during playback. They are similar (but not identical) to the RIAA curves for vinyl records.

Here is a diagram showing the Record Pre-Emphasis Curve and the Playback Post-Emphasis Curve for NAB, CCIR, and RIAA:

The bias frequency of the B77 MK III is 125 kHz. This accompanies the musical frequencies applied during the recording procedure in the record head, improving the quality of magnetizing the iron particles on the tape.

Higher bias frequencies offer several advantages:

Greater separation from audio — With 125 kHz bias, even if some residual signal leaks through, it’s more than six octaves above 20 kHz. Any intermodulation products between the bias and high audio frequencies stay well clear of the audible band. A 15 kHz tone intermodulating with 125 kHz produces difference frequencies around 110 kHz, completely inaudible. With a lower bias frequency like 60 kHz, that same intermodulation lands at 45 kHz, closer to where it might cause trouble.

More bias cycles per gap crossing — As the tape traverses the record head gap, the particles need to undergo multiple complete magnetization cycles for proper anhysteretic behavior. At 15 IPS with a typical record gap, higher bias frequency ensures more oscillations occur during the brief transit time, resulting in more thorough linearization.

Improved high-frequency recording — The bias signal can partially erase very high audio frequencies if its wavelength approaches theirs. A higher bias frequency keeps its recorded wavelength much shorter than any audio signal, minimizing this self-erasure effect on treble.

Better erasure — Since the erase head shares the same oscillator, higher frequency means more demagnetization cycles as tape passes the erase gap, ensuring more complete erasure.

The tradeoffs are increased losses in head windings at higher frequencies and greater demands on the oscillator circuit. At 125 kHz, Revox chose a frequency that optimizes performance at the B77’s higher tape speeds while remaining practical to implement. Some older or less sophisticated decks used 60–80 kHz, which works but offers less margin.

Revox has converted to using film capacitors instead of electrolytics that were in previous models.

Film capacitors offer several advantages over electrolytic capacitors in audio circuits:

Lower dielectric absorption — This is perhaps the most significant benefit for audio. Electrolytic capacitors exhibit “memory” or “soakage,” where they retain a residual charge after being discharged, which can smear transients and blur fine detail. Film capacitors release their charge cleanly, preserving the sharp edges of musical transients.

Better long-term stability — Electrolytic capacitors rely on a liquid or gel electrolyte that dries out over time, causing capacitance drift and increased ESR (equivalent series resistance). This is why vintage equipment often needs capacitor replacement after 20 – 30 years. Film capacitors use solid plastic dielectrics, polypropylene, polyester, or polystyrene, that remain stable for decades.

Lower distortion — The dielectric material in film capacitors behaves more linearly under varying voltage conditions. Electrolytics can introduce subtle nonlinearities, particularly at low signal levels.

Lower noise — Film capacitors generate less thermal noise than electrolytics, contributing to a quieter noise floor.

Tighter tolerances — Film capacitors are typically available with 1 – 5% tolerance versus 20% or worse for electrolytics, ensuring better channel matching and more predictable circuit behavior.

No polarity concerns — In signal path applications, non-polarized film capacitors simplify design and eliminate the risk of reverse-voltage damage.

The tradeoff is size and cost; film capacitors are physically larger and more expensive for equivalent capacitance values. Revox’s choice to use them throughout the B77 MK III reflects their commitment to long-term reliability and audio purity.

The B77 MK III has three motors: one for Play and Fast Forward, one for the capstan (controls tape speed when playing or recording), and one for Fast Rewind.

The front of the B77 MK III has all the standard tape deck features: power on/off switch, choice of 7-1/2 ips or 15 ips tape speeds, monitor tape vs. line, playback volume control for the headphone jacks, choice of listening in stereo, left, or right, and reverse channels, record left and record right on/off switches, input level for left and right channels, choice of line inputs or mic inputs, mic sockets, left and right channel meters, digital tape counter, and the main functions buttons; pause, rewind, fast forward, play, stop, and record. There is also a tape splicing table. You can click on the photo below and zoom in to see the details.

Here is a photo of the main set of controls and the VU meters. The meters’ range is -20 dBVU to +3 dBVU. A clipping light (bottom center of the meters) flashes if the signal goes above +3 dBVU. I found that this occasionally occurred when playing pre-recorded tapes that were recorded “hot”. Notice the REC●R switch on the left. This, plus the REC●L switch, has to be in the up position for recording. This is one of the safety features to prevent recording over tape that already has music on it that you don’t want to damage.

The rear panel has the input and output connections, all of which are XLR balanced connectors.

Some of the features on the B77 MK III were taken from the PR99, which was a broadcast version of the B77. These include the XLR connections, digital length and time counter, choice of CCIR (EIC) or NAB EQ, 7-1/2 IPS and 15 IPS, and half-track vs. quarter-track, so the B77 MK III is a combination of both deck models.

Secrets Sponsor

In my reference 2-channel system, I listened to the Revox B77 MK III using a Pass Labs XP-32 Preamplifier, the Balanced Audio Technology VK-500 Power Amplifier, and the Sonus faber Lillium loudspeakers. Speaker and interconnect cables were courtesy of Clarus Cables. For personal listening, I used the Sennheiser HD 660S headphones and the OPPO PM-1 Planar Magnetic headphones with an OPPO HA-1 Headphone Amplifier.

Jason Roebke Quartet, Shimmering, December 2012 — Chicago, Illinois – Tape from International Phonograph, Inc.

From the liner notes: “Performed on December 18th of 2012 in Chicago, this performance was recorded directly to a custom 8-track Studer recorder. This great ensemble of world-class players features Chicago-style modern jazz at its best (Jason Roebke, bass; Mike Reed, drums; Jason Adasiewicz, vibes; and Keefe Jackson, tenor sax). Although the jazz is somewhat avant-garde, it is also quite lyrical and captivating to listen to on tape. A handmade stereo mic was used on the vibes, and a hand-assembled Telefunken 251e was used on the tenor sax. (Text by Jonathan Horwich – Owner of International Phonograph, Inc.)”

The track “Shimmering” opened with Jason playing a bass solo, followed by a Vibraphone (“Vibes”) intro. The bass sounded much like a digital recording because the notes are very low frequency, but the sound of the vibes was shockingly smooth and silky, like no digital recording I’ve heard. (A vibraphone is a pitched percussion instrument with tuned aluminum bars, similar to a xylophone but with metal bars and resonator tubes, producing a mellow, sustained, or vibrato-rich sound often used in jazz and orchestras, played with cord-wrapped mallets and featuring a sustain pedal and rotating discs in the resonators for a unique pulsing effect.)

Bobby Broom Trio, Sweet and Lovely, March 2014 – Chicago, Illinois – Tape from International Phonograph, Inc.

From the liner notes: “Bobby Broom continues to create stellar jazz, whether with Sonny Rollins, or luckily for us, this time on tape with his amazing Chicago trio consisting of Dennis Carroll on bass and Makaya McCraven on drums. This is simply one of the finest guitar trios in jazz. Each member is a vital part of the performance, playing off each other while displaying a gorgeous laid-back energy only musicians of this caliber can pull off. Recorded to a custom 8-track analog tape recorder and using only the finest vintage microphones, this is modern, multi-track analog sound at its most natural. Engineering by Anthony Gravino of High Cross Sound, as assisted by Jonathan Horwich- Owner of International Phonograph, Inc.”

On the track “Tennessee Waltz,” Bobby Broom opens alone on guitar, making it easy to focus on tone, articulation, and dynamics. The guitar has a warm, natural balance, but the individual string plucks remain clearly defined. You can hear both the resonance of the instrument and the initial attack of each note without either being exaggerated.

Played back on the Revox B77 MK III, transients are handled cleanly and without edge. Attacks arrive promptly but never sound sharp or aggressive, and there is no added glare. The sustain and decay of notes are reproduced smoothly, allowing the instrument to sound continuous and stable rather than fragmented. Spatial cues are well preserved, giving a realistic sense of the recording environment. Overall, the presentation is easy to listen to for long periods, with accurate timing and dynamics, and without the fatigue that can sometimes accompany more forward or analytical playback.

Lee Konitz / Martial Solal, The Portland Sessions, February 1979 – Portland, Oregon – Tape from International Phonograph, Inc.

From the liner notes: “Lee Konitz is considered by many, including this writer, to be a genius in jazz. His historic work with Warne Marsh as part of the Tristano school of jazz has never been surpassed. Later, after his work in the Tristano school, his tone and harmonies moved away from that strict structure into something very much his own — and very classical and European. Here, Konitz is in duet with the great European pianist, Martial Solal, whose playing complements and interweaves with Konitz perfectly. The playing is stellar. Fortuitously, I captured the performance on a Levinson/Studer ML5 30ips tape deck, with just two B&K omnidirectional instrument microphones, in a gorgeous hall on one of the greatest pianos ever built, the Mark Allen concert grand. After hearing this recording several times recently, I believe it embodies all that I have tried to achieve with jazz in concert with great audio. A musical and audio gem. (Text by Jonathan Horwich – Owner of International Phonograph, Inc.)”

With only two musicians, the recording is very exposed: tenor saxophone and piano, Lee Konitz and Martial Solal, with no other instruments to mask balance or detail. This makes it easy to hear how closely the two players listen and respond to each other. Konitz is positioned on one side of the soundstage, with Solal on the other, creating clear spatial separation while still maintaining a cohesive image. Their musical lines frequently overlap and interact across the stereo field rather than remaining isolated.

Konitz’s saxophone tone is relaxed and controlled, with audible breath and subtle dynamic shading. Solal’s piano provides harmonic structure and rhythmic support without overpowering the saxophone. On tape, the balance between the two instruments is well judged, with good weight and clarity and no sense of edge or glare. The pauses between phrases are clearly defined, contributing to a natural sense of timing and flow that makes the recording easy and engaging to follow.

Frank Strazzeri, That’s Him, March 1969 — Los Angeles, California – Tape from International Phonograph, Inc.

From the liner notes: “Let’s get right to the point of this performance: This is one of the finest piano trio outings ever recorded. This is a bold statement indeed, but in this case, true. Repeated listening (over 25 times) has revealed this as a true jazz masterpiece of harmonic nuance and brilliance. Frank needs no introduction nor a listing of his accomplishments as a pianist. He has transformed his many influences (Bud Powell, Horace Silver, Hank Jones, etc.) into an impeccable, concise, brilliant style. And while manifesting a crisp and bright sound, you won’t find one cliché in Frank’s playing. Recorded in 1969 on a vintage Scully 4-track tape deck by John William Hardy, this piano trio session is classic studio sound and wholly complementary to the playing. (Text by Jonathan Horwich – Owner of International Phonograph, Inc.)”

This piano, bass, and drums trio is a familiar format, but it immediately shows its strengths when played back from tape. As a jazz drummer, I focused on the ride cymbal, which is one of the most challenging instruments to reproduce accurately due to its wide range of overlapping frequencies. It includes a sharp initial attack, a complex metallic body, and a long decay that can easily become smeared or exaggerated.

On this recording, the ride cymbal is reproduced with good balance. The attack is clearly defined, the shimmer is present without sounding brittle, and the decay extends smoothly without collapsing into noise. The cymbal integrates naturally into the acoustic space rather than sounding detached or flattened. Modern digital playback can approach this level of realism, but tape still tends to retain slightly more of the cymbal’s harmonic complexity, making it sound closer to an actual vibrating piece of metal rather than a simplified representation.

Dave Samuels Vibes Trio, September 1980 – New Haven, Connecticut – Tape from International Phonograph, Inc.

From the liner notes: “Here we have highly talented musicians in a highly unusual configuration, both musically and sonically. It is very uncommon to hear a trio consisting of vibes (Dave Samuels), piano (Andy LaVerne), and bass (Mike Richmond). And it’s almost impossible to hear such a group recorded with only two omnidirectional microphones. But that is the case here, and the musical and audio result is stunning. It is one of the best jazz recordings I have ever made with only two spaced omnidirectional microphones. But more importantly, the playing is world-class, with some of the greatest musicians from New York City performing at the Educational Center for the Arts in New Haven, Connecticut. You’ll rarely hear the vibes played as well as Dave Samuels plays them. And you will rarely experience such an unusual (and stellar) group recorded with such naturalness as is heard here. I consider this the recording I’m most proud of, as it was very difficult to record with just two microphones and achieve this sound quality. (Text by Jonathan Horwich – Owner of International Phonograph, Inc.)”

I was impressed by the sound of the vibraphone on the Jason Roebke Quartet album Shimmering, which led me to seek out a recording where the instrument was more exposed. This album provides that opportunity, with the vibraphone clearly presented and not masked by dense accompaniment. With the instrument placed prominently in the mix, its characteristic shimmer is easy to hear throughout the performance. The initial attack is clean and well defined, followed by a sustain that remains smooth and continuous.

It is difficult to say exactly why analog playback presents the vibraphone this way. It may be related to the continuous nature of the signal path, or to the frequency response and behavior of tape. Regardless of the cause, the result is a presentation that preserves note decay and harmonic overlap in a natural way. The instrument sounds stable and coherent over time, which makes extended listening both engaging and comfortable.

Yello, “One Second”, Revox/Horchhouse

One Second is Yello’s fifth original studio album, having been preceded by a ‘new mix’ compilation the previous year. Released in 1987, the album is noteworthy for featuring both Billy Mackenzie and Shirley Bassey, the latter singing vocals on “The Rhythm Divine”. The songs “Call It Love”, “Si Señor The Hairy Grill”, “Moon On Ice”, and “Hawaiian Chance” were used on episodes of Miami Vice, and the song “Santiago” was used as a sample from Dunya Yunis’ “Abu Zeluf”. A couple of songs were also used in the 1990 film Nuns on the Run. The song “Si Señor The Hairy Grill” was used as the theme song for the Fox TV show The Edge.

One Second is an impressive example of how much sonic complexity can be created by just two musicians. Yello’s layered electronic textures, synthesized percussion, and processed vocals are dense and highly detailed, which can sometimes make electronic music sound sharp or fatiguing on highly revealing systems. On tape, however, this album benefits from a more controlled presentation.

The overall complexity of the arrangements is fully preserved; rhythmic layering, spatial effects, and fine detail remain intact, but the leading edges of transients are slightly softened in a way that improves long-term listenability. Sharp attacks from synthesized percussion and high-frequency effects are smoother and less edgy, without sounding blurred or dull. This allows the music to retain its energy and precision while reducing listening fatigue. The result is a presentation that feels balanced and composed, rather than aggressive. Tape seems to moderate the inherent hardness of some electronic sounds, making the album easier to listen to at higher levels and for longer sessions, while still clearly conveying the intent and structure of the production. (Here is a link to the album: https://www.horchhouse.com/en-us/products/yello-one-second?variant=55766769729871)

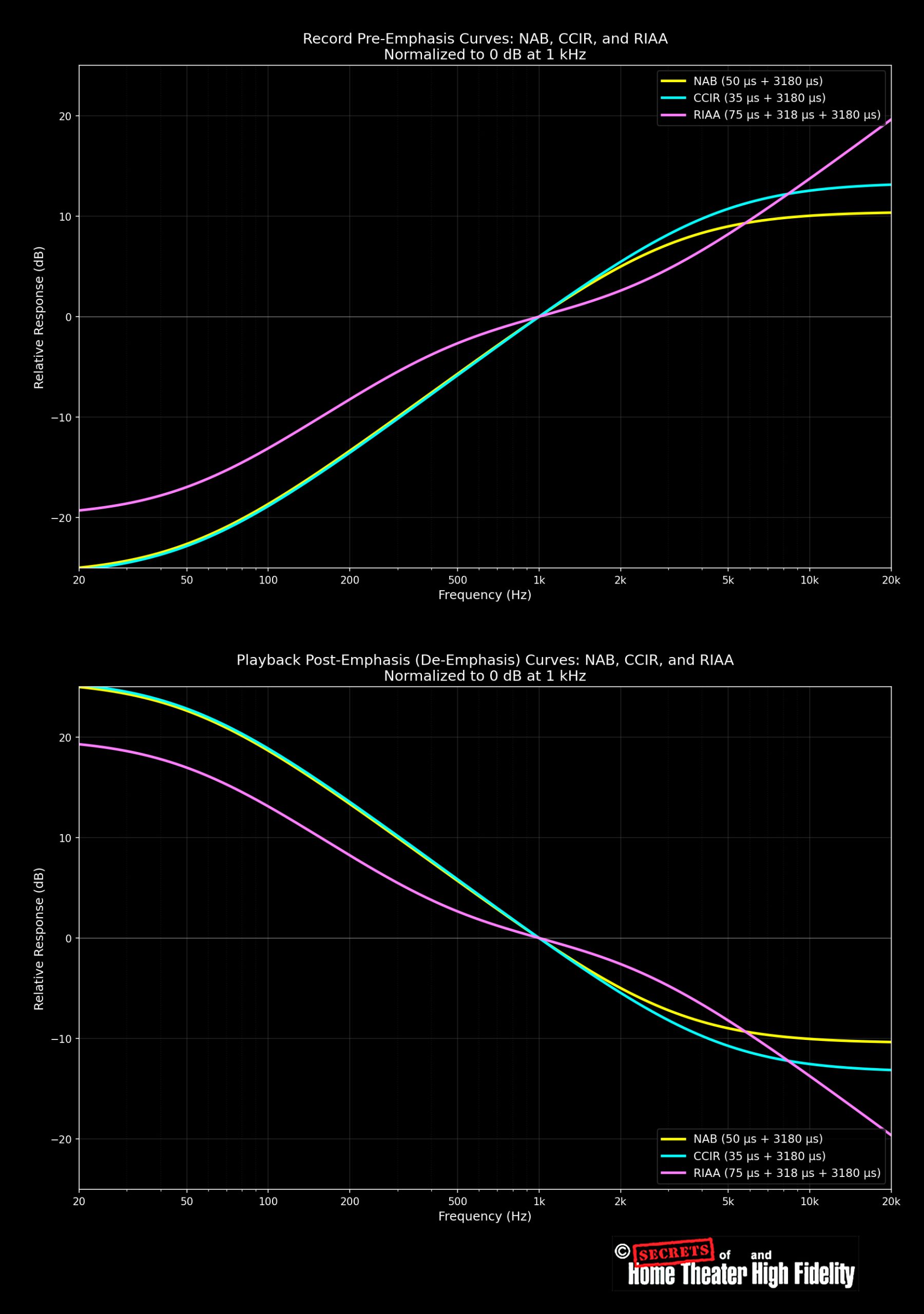

Figure 1 represents a 1 kHz sine wave at 0 dBVU (1 volt input, 0.422 Volts output at 0 dBVU) using a 320 nWb/m Flux setting. All tests below are at 15 IPS except for the specific set of tests at 7-1/2 IPS labeled as such. Note the significant amount of 2nd-ordered and 3rd-ordered harmonics, and the comparative lack of higher-ordered harmonics. THD+N was 0.65%, and THD was 0.079%, so noise was the most contributing factor, namely tape hiss, and that is something almost impossible to eliminate. It is inherent to analog tape. However, I could not hear any hiss unless I waited for the silence in between tracks and turned up the volume. So, distortion by itself was less than 0.01%, which is a good result. There is a hum bar at 60 Hz, -63 dBV. It is significant, but I could not hear it even with headphones. The B77 MK III does not have a ground pin in the AC cable or jack, so you should probably ground it to your other equipment by connecting the chassis.

Regarding harmonics:

The preference for even-order harmonics is well established, but it’s nuanced.

The 2nd harmonic is the most desirable; it’s exactly one octave above the fundamental, so it reinforces the note in a completely consonant way. It adds warmth and fullness without changing the perceived pitch or introducing dissonance. This is the primary harmonic that gives tubes and tape their “musical” character.

The 3rd harmonic is more complex. It sits an octave and a fifth above the fundamental, which is still musically consonant; it’s part of the natural overtone series. In moderate amounts, it adds presence and richness. However, as the 3rd harmonic distortion increases, it can become harsh or “boxy.” Small amounts are often acceptable; large amounts are not.

The 4th harmonic is two octaves up, again perfectly consonant and generally pleasant, though less impactful than the 2nd since it’s further removed from the fundamental.

Higher odd-order harmonics (5th, 7th, 9th) are where things get problematic. These fall at increasingly dissonant intervals and produce the hard, edgy, “transistor” sound associated with clipping solid-state amplifiers. The 7th harmonic is particularly grating.

Higher even-order (6th, 8th) remain relatively benign because they maintain octave relationships with lower even harmonics, but they contribute less warmth and more “presence.”

In a nutshell: 2nd is golden, 4th is fine, 3rd is acceptable in moderation, and higher odd-orders are what you want to avoid.

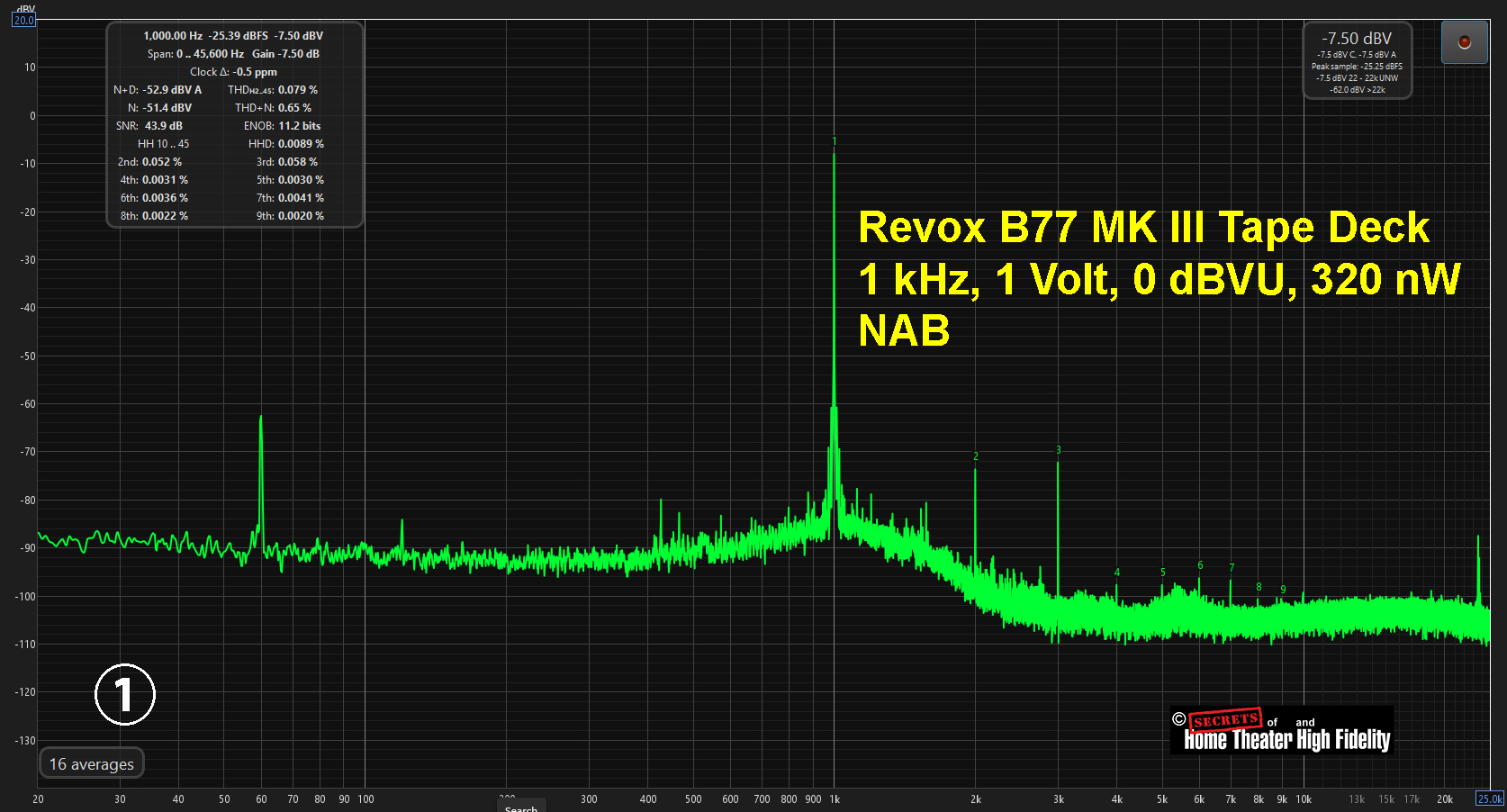

Figure 2, below, shows the same test but with a 510 nWb/m Flux setting. THD+N was 0.61% (a bit lower than at 320 nWb/m), and THD was 0.16% (higher than at 320 Wb/m), so noise was lower, but distortion was higher. This is why I have chosen 320 nWb/m, even though this blank tape (RTM S900) can be recorded at 510 nWb/m.

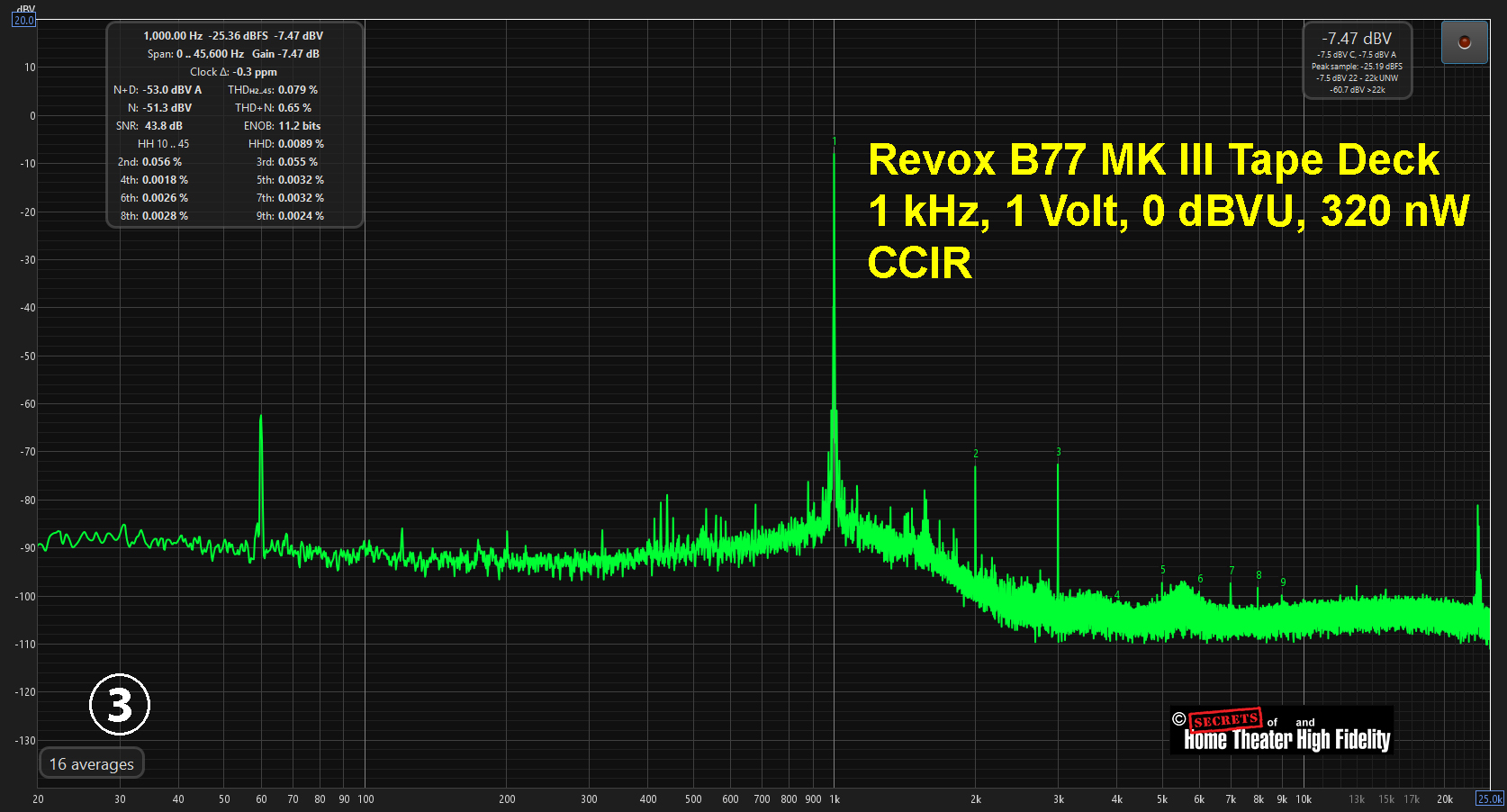

In Figure 3, I used CCIR EQ and 320 nWb/m Flux. THD+N was 0.65%, and THD was 0.079%, just like with NAB EQ.

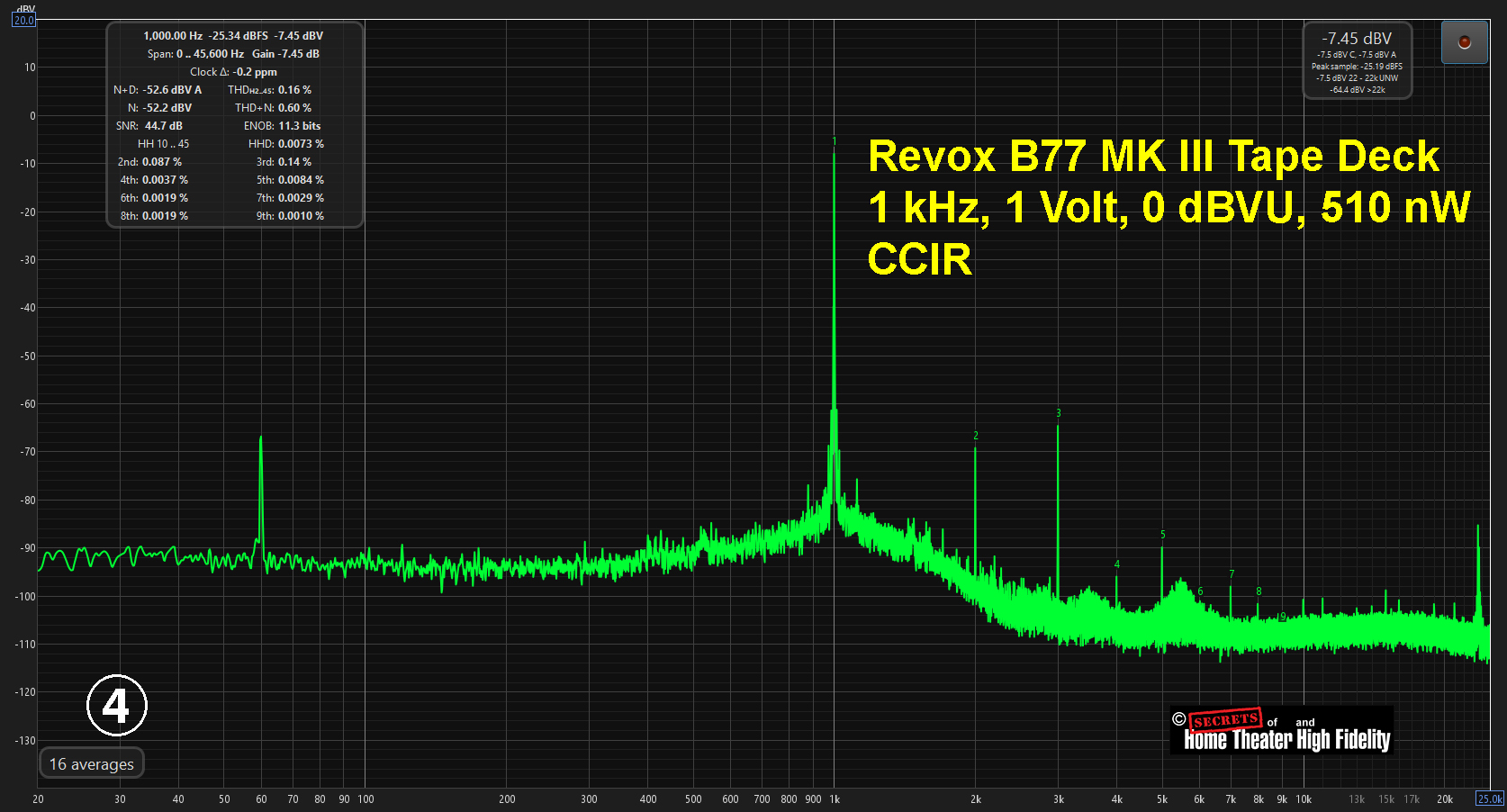

Figure 4 is with 510 nWb/m. THD+N was 0.60%, and THD+N was 0.16%, essentially the same as with NAB EQ.

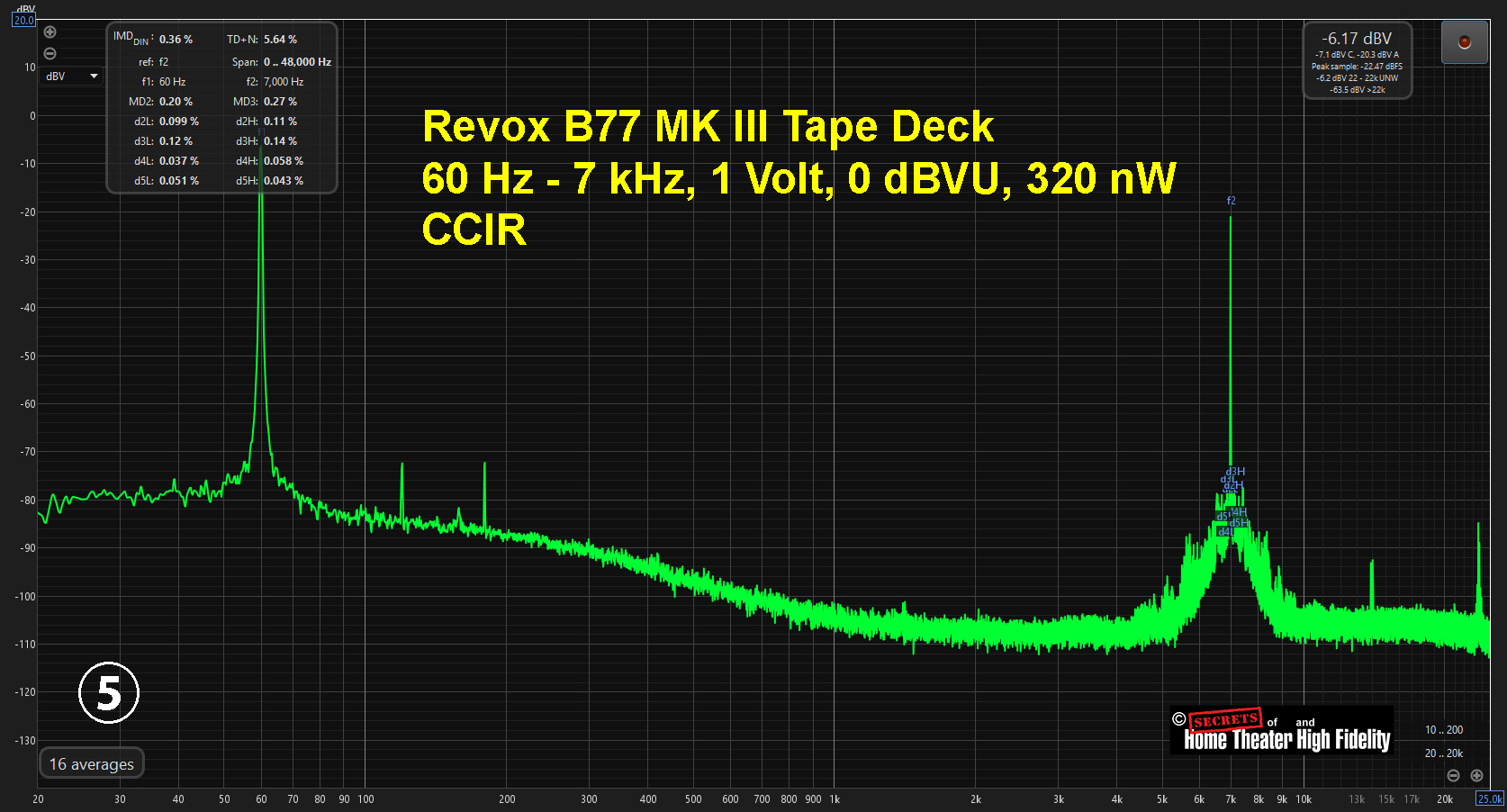

Moving on to Intermodulation Distortion (IMD), it was 0.36% with CCIR EQ and 320 nWb/m Flux (Figure 5).

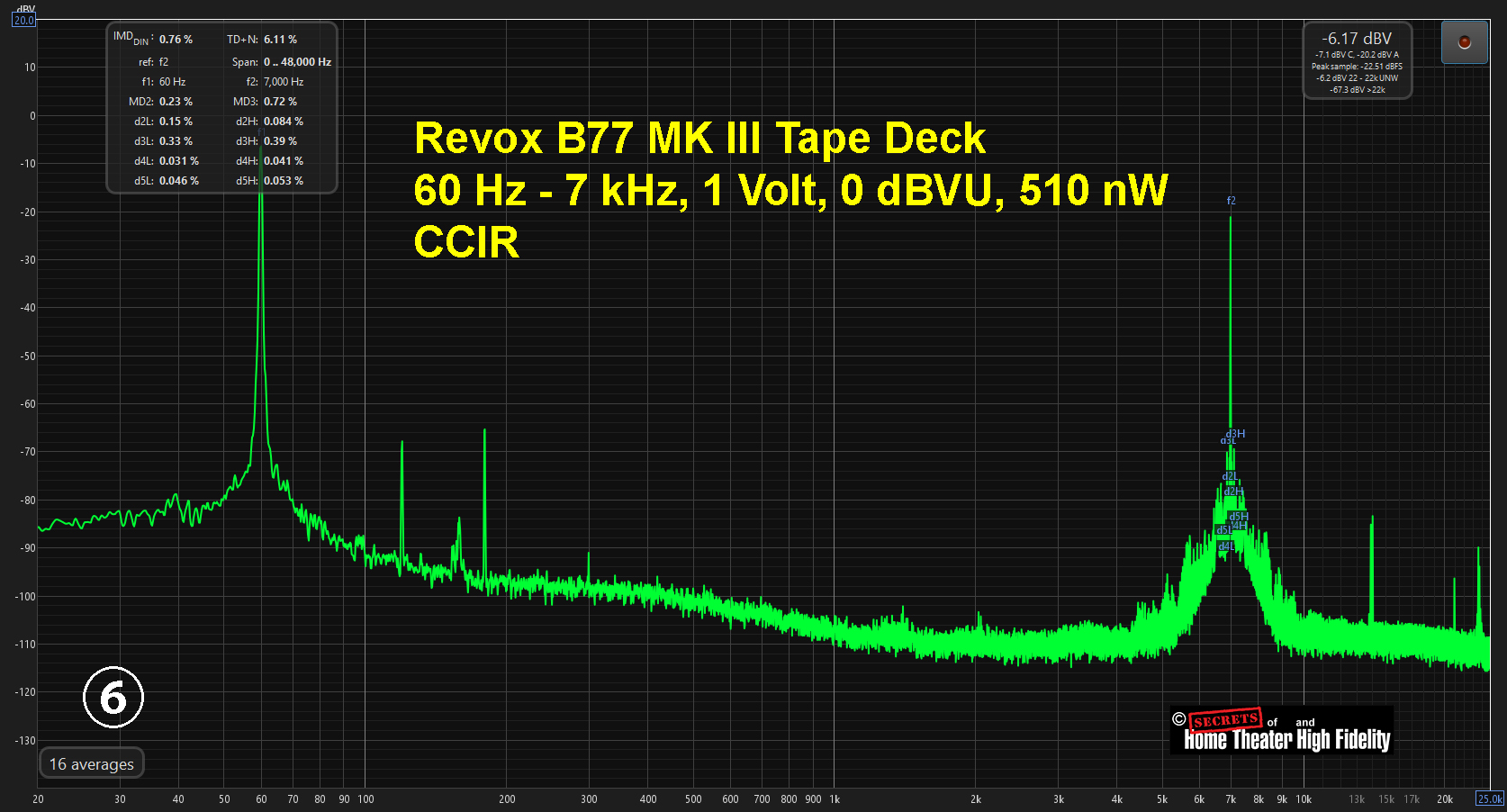

And at 510 nWb/m, IMD was 0.76%, again, higher than with 320 nWb/m Flux. Note that all subsequent tests were with CCIR EQ and 320 nWb/m Flux. CCIR because that is what most modern pre-recorded tape manufacturers use.

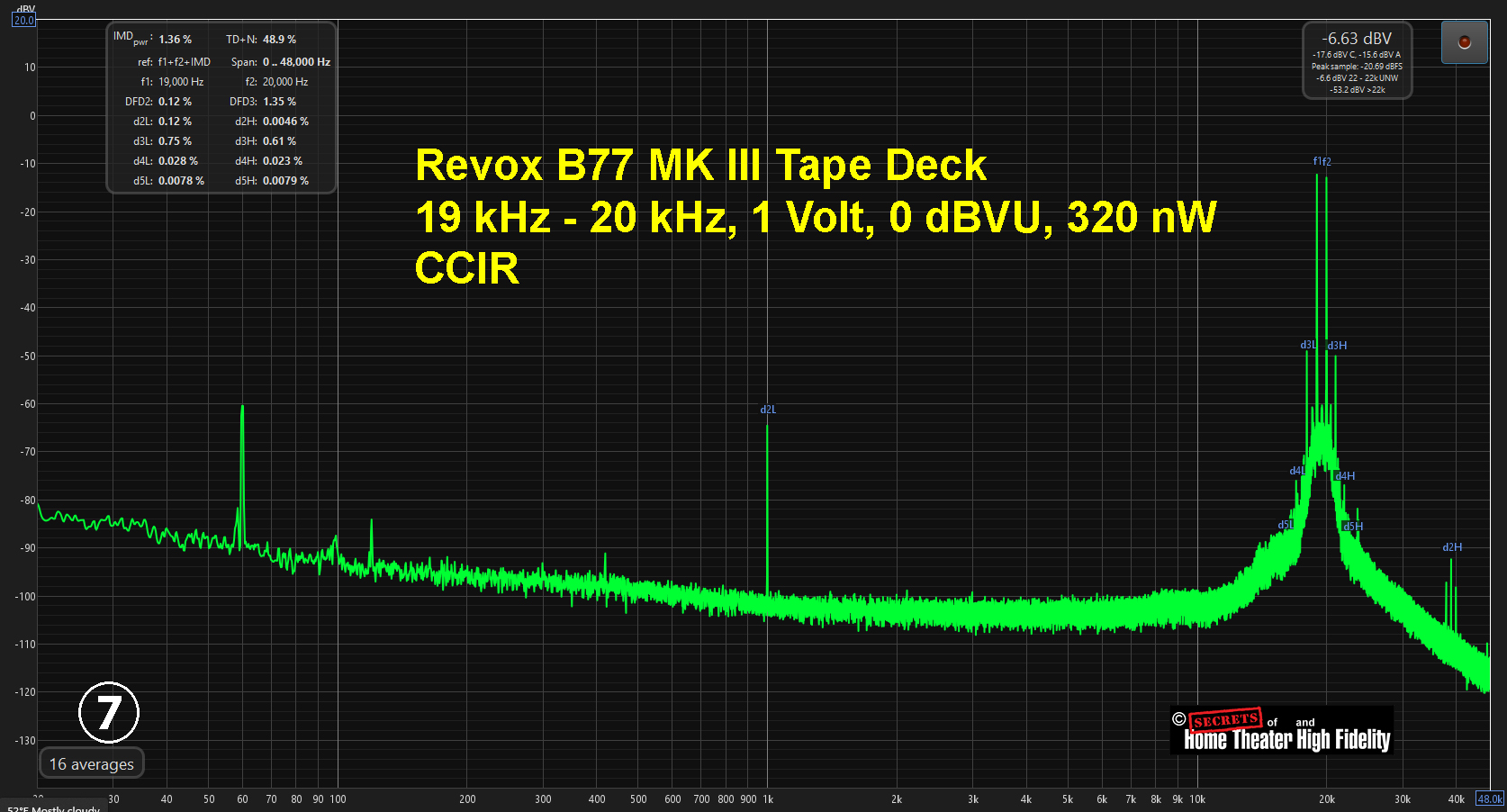

19 kHz – 20 kHz, 320 nWb/m is shown below in Figure 7. There is a significant B-A (20 kHz minus 19 kHz) peak at 1 kHz, -64 dBV.

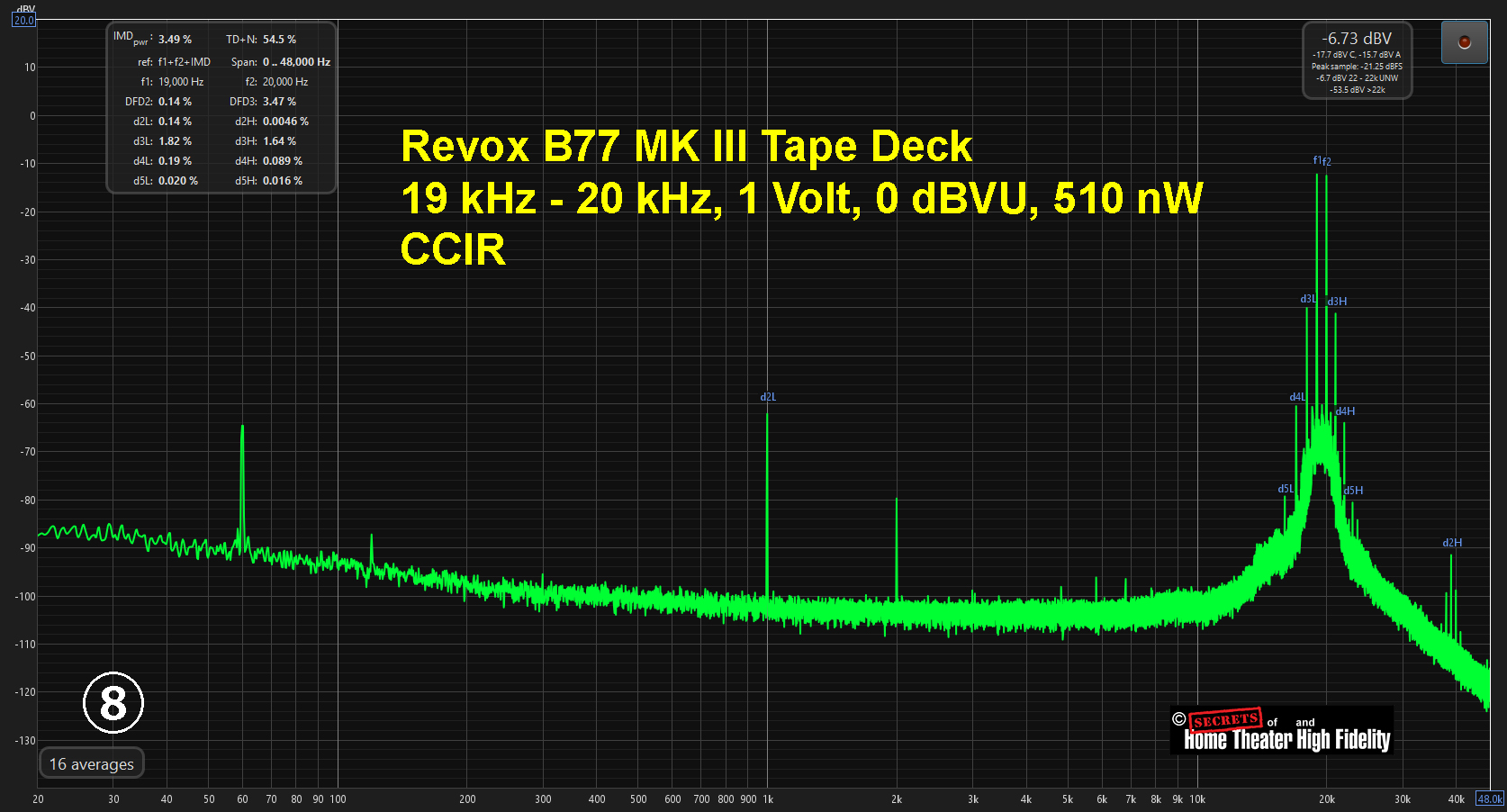

And at 510 nWb/m (figure 8), the B_A peak is a bit higher at -63 dBV.

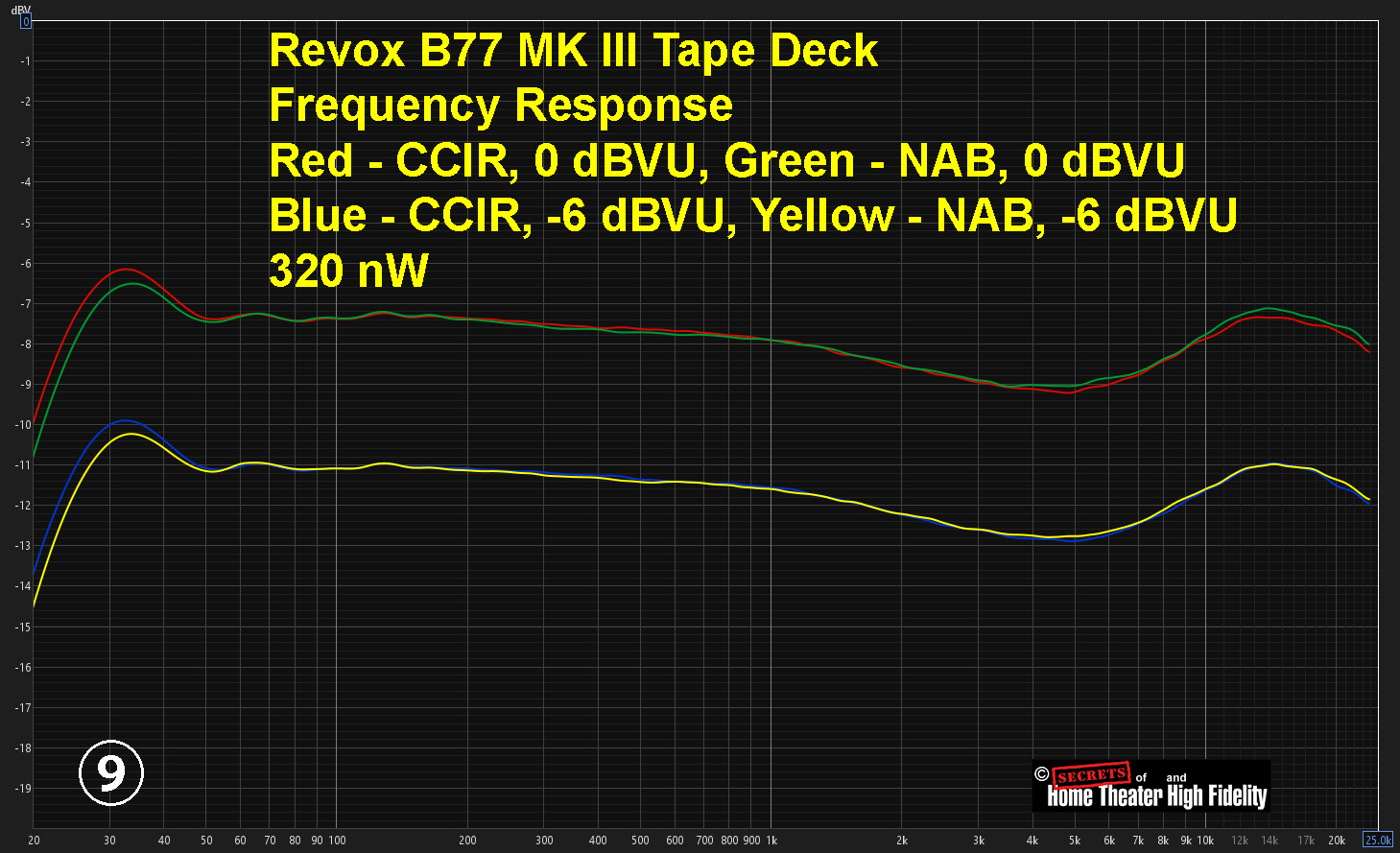

The frequency response is shown in Figure 9 below for CCIR and NAB, at 0 dBVU and -6 dBVU, with a sensitivity of 320 nWb/m. You can see that there is a small difference between CCIR and NAB. The hump at 30-40 Hz is a natural occurrence with magnetic tape, but it is slightly higher (0.5 dBV) with CCIR EQ. At 15 kHz, the response is a bit lower (0.3 dBV) with CCIR EQ.

Frequency Response Analysis: Revox B77 Mk III at 15 IPS

The frequency response curves shown represent measurements at 0 dBVU and −6 dBVU using both CCIR and NAB equalization standards at 15 IPS. The response falls to within 1.5 dB across the audible spectrum, meeting the published specifications for this deck, which retails for nearly $20,000. This performance represents the practical limits of analog magnetic recording technology, even for high-end consumer equipment.

The low-frequency contour visible around 30 – 40 Hz demonstrates the classic “head bump” phenomenon—a resonance artifact arising from the playback head geometry and the coupling behavior of magnetic flux at long wavelengths. This effect proves difficult to eliminate entirely regardless of price point, as it stems from fundamental electromagnetic interactions between the head gap and tape oxide.

The midrange flatness from approximately 100 Hz to 2 kHz represents tape recording at its best, where wavelength-to-gap ratios are optimal and neither low-frequency head effects nor high-frequency losses dominate. The gentle undulations appearing in the treble region reflect the cumulative influence of head azimuth alignment precision, bias current optimization, and the specific magnetic characteristics of the tape formulation in use.

The close tracking between CCIR and NAB curves at both recording levels indicates consistent equalization circuit performance, while the minimal deviation between 0 dBVU and −6 dBVU traces confirms good linearity across the deck’s operating range. These results illustrate why analog tape, despite its inherent physics constraints, remained the professional recording standard for decades—achieving musically satisfying performance within well-understood physical boundaries.

Frequency Response Variations and Phase Shift

Any amplitude variation in a minimum-phase system has an associated phase shift, and most of the mechanisms causing the tape’s frequency response irregularities are minimum-phase in nature.

The head bump around 30 – 40 Hz is essentially a resonance, and resonances always involve phase rotation. The phase leads on the rising slope below the peak frequency, then lags on the falling slope above it. There are, perhaps, 20 – 30 degrees of phase shift through that region.

The high-frequency rolloff from gap losses similarly introduces phase lag that accumulates as frequency increases. The playback equalization circuits that boost highs to compensate add their own phase characteristics. Even if the amplitude ends up reasonably flat after EQ, the phase response reflects the sum of all these corrections.

The mathematical relationship is described by the Hilbert transform; for minimum-phase systems, amplitude and phase aren’t independent. If you know the complete amplitude response, you can calculate the phase response, and vice versa. This is sometimes called the Kramers-Kronig relation.

Whether these phase shifts are audible is debated. Some argue that the ear is relatively insensitive to phase at low frequencies, while others believe the cumulative phase wander across the spectrum contributes to tape’s characteristic “warmth” or “depth.”

What’s certain is that the response I measured, while impressively flat in amplitude, carries a more complex phase signature underneath—another layer of the analog character that makes tape sound like tape.

The record pre-emphasis and playback post-emphasis (de-emphasis) are designed as complementary inverse filters. If the playback EQ is precisely the mirror image of the record EQ, the phase shifts they introduce cancel. You put a signal through a high-frequency boost with its associated phase lead, then through the matching cut with its phase lag, and you’re back where you started. The CCIR and NAB equalization curves, when properly implemented, are phase-neutral as a pair.

What remains uncorrected are the phase shifts introduced by the tape medium and heads themselves; the parts of the chain that the EQ curves are compensating for in amplitude but not in phase. The head bump resonance, gap losses, spacing losses, the magnetic hysteresis of the oxide, eddy currents in the head cores, these physical phenomena introduce phase shifts that no standard EQ curve addresses. The equalization restores a flat amplitude response by boosting or cutting the appropriate frequencies, but those amplitude corrections don’t automatically fix the phase anomalies caused by the recording physics.

So, you end up with a system where the electronics are essentially phase-transparent (EQ in, EQ out, net zero), but the electromechanical transduction process, heads, and tape leave their phase signature on the signal. That’s where tape’s residual phase character lives, not in the equalization chain itself.

In professional tape decks, there are usually small potentiometers for more EQ to flatten the frequency response, but doing that adds more phase shift. Revox has chosen not to do that with the B77 MK III, but rather to just let the frequency response fall where it may, and not to induce even more phase shift. I can’t argue with this philosophy, as the B77 MK III sounds fantastic.

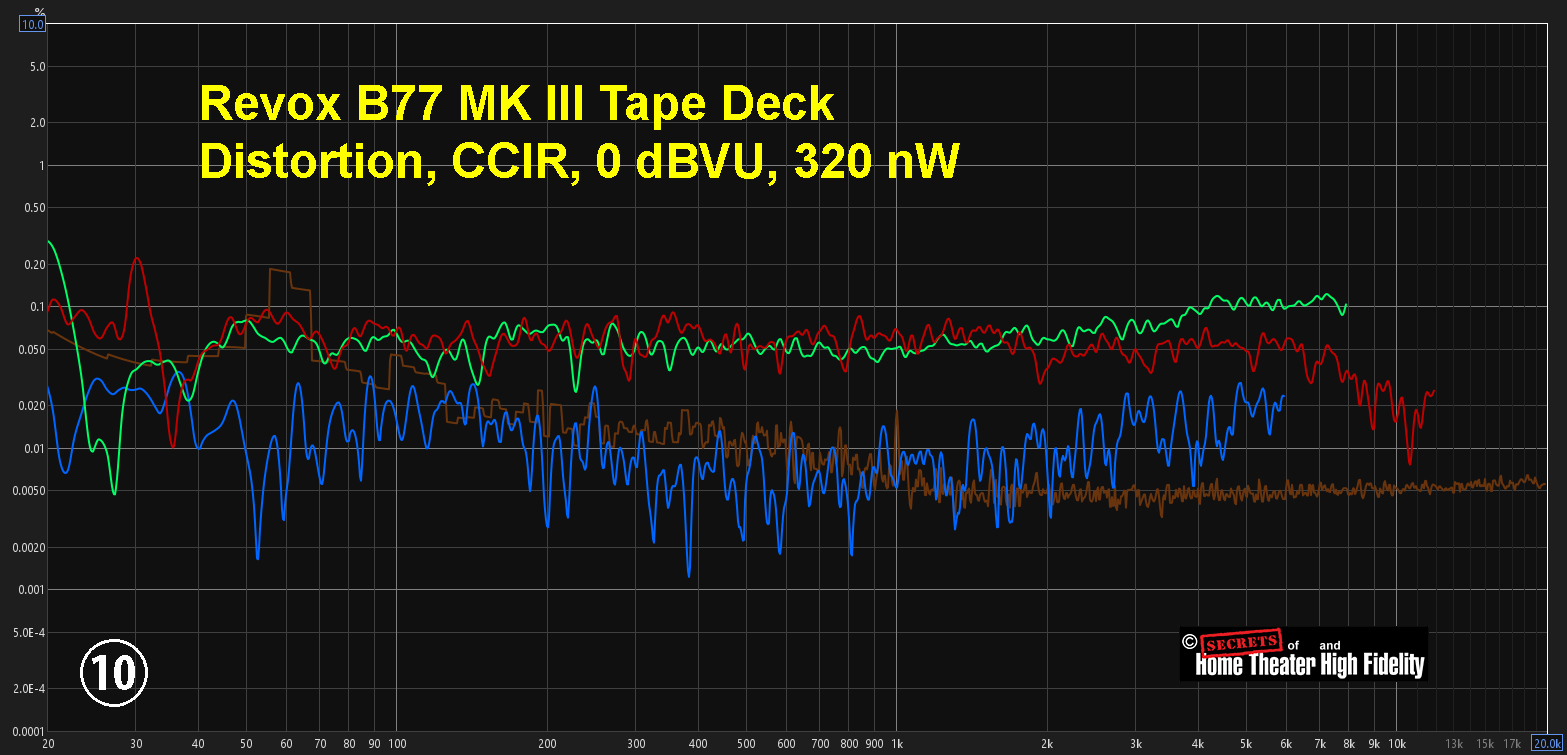

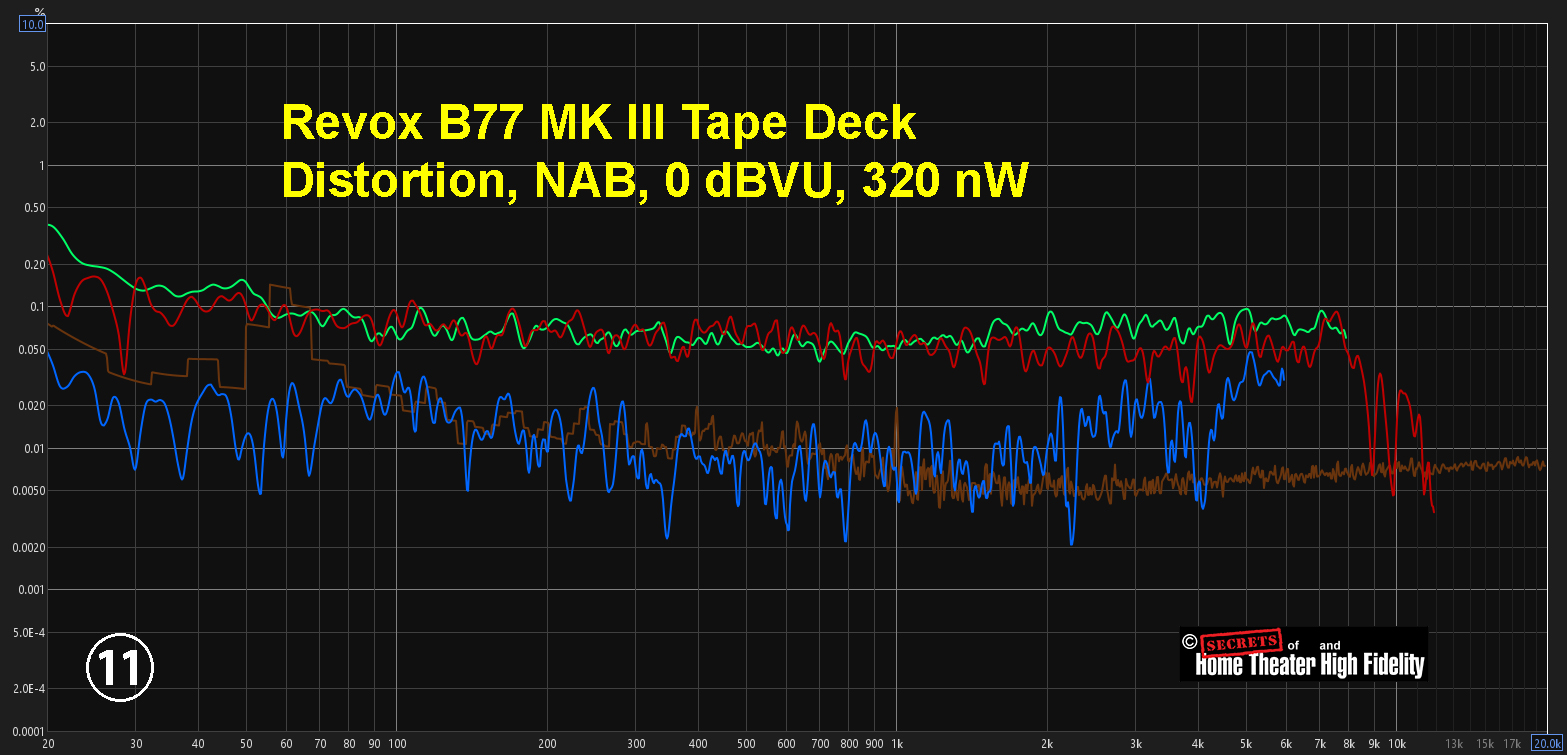

Distortion for CCIR at 0 dBVU is shown in Figure 10. Red is the 2nd-ordered harmonic, green is the 3rd, and blue is the 4th.

Figure 11 is with NAB EQ. 3rd-ordered harmonics are higher at the very low frequencies.

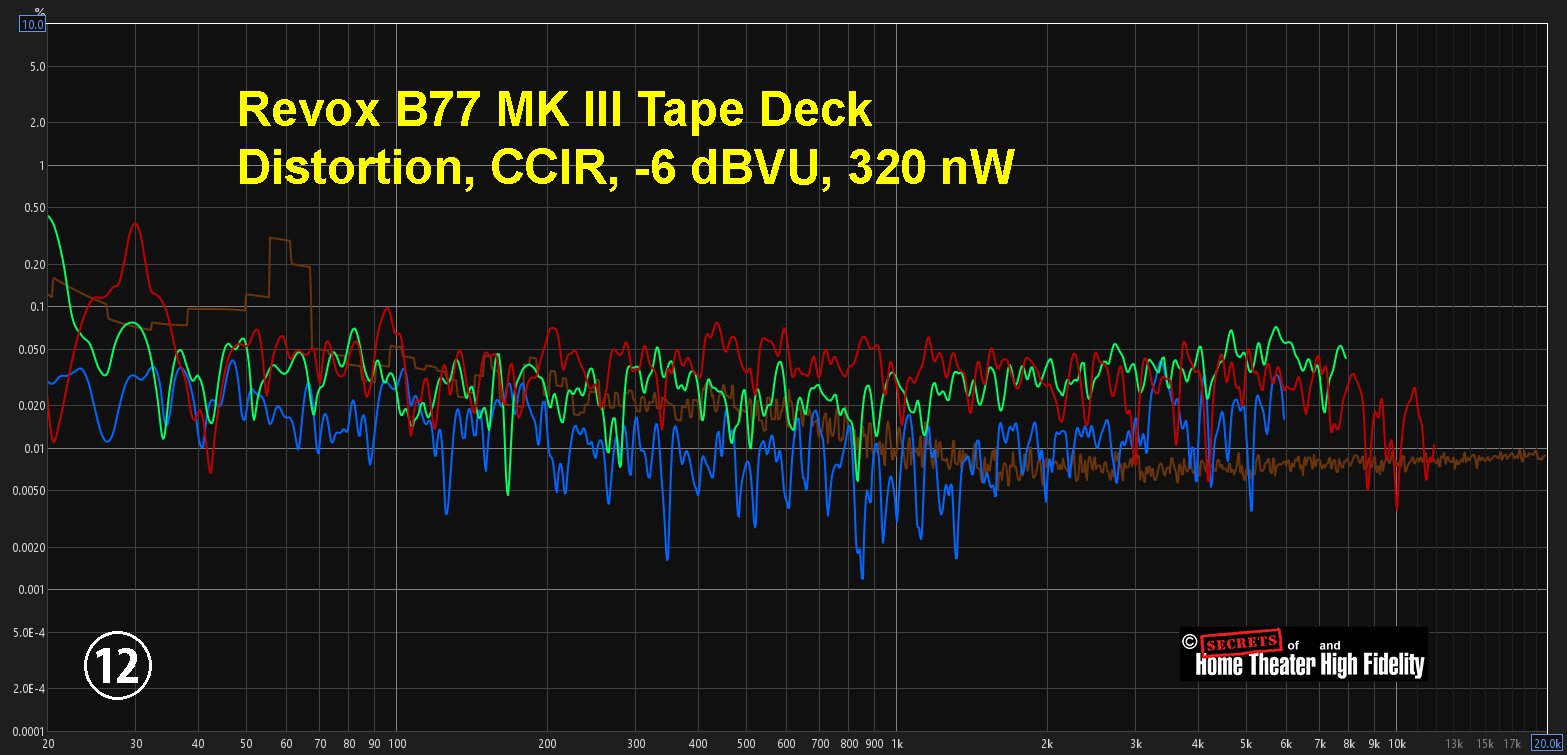

Distortion at -6 dBVU, CCIR, is shown in Figure 12. 2nd-ordered harmonics are more prominent than at 0 dBVU.

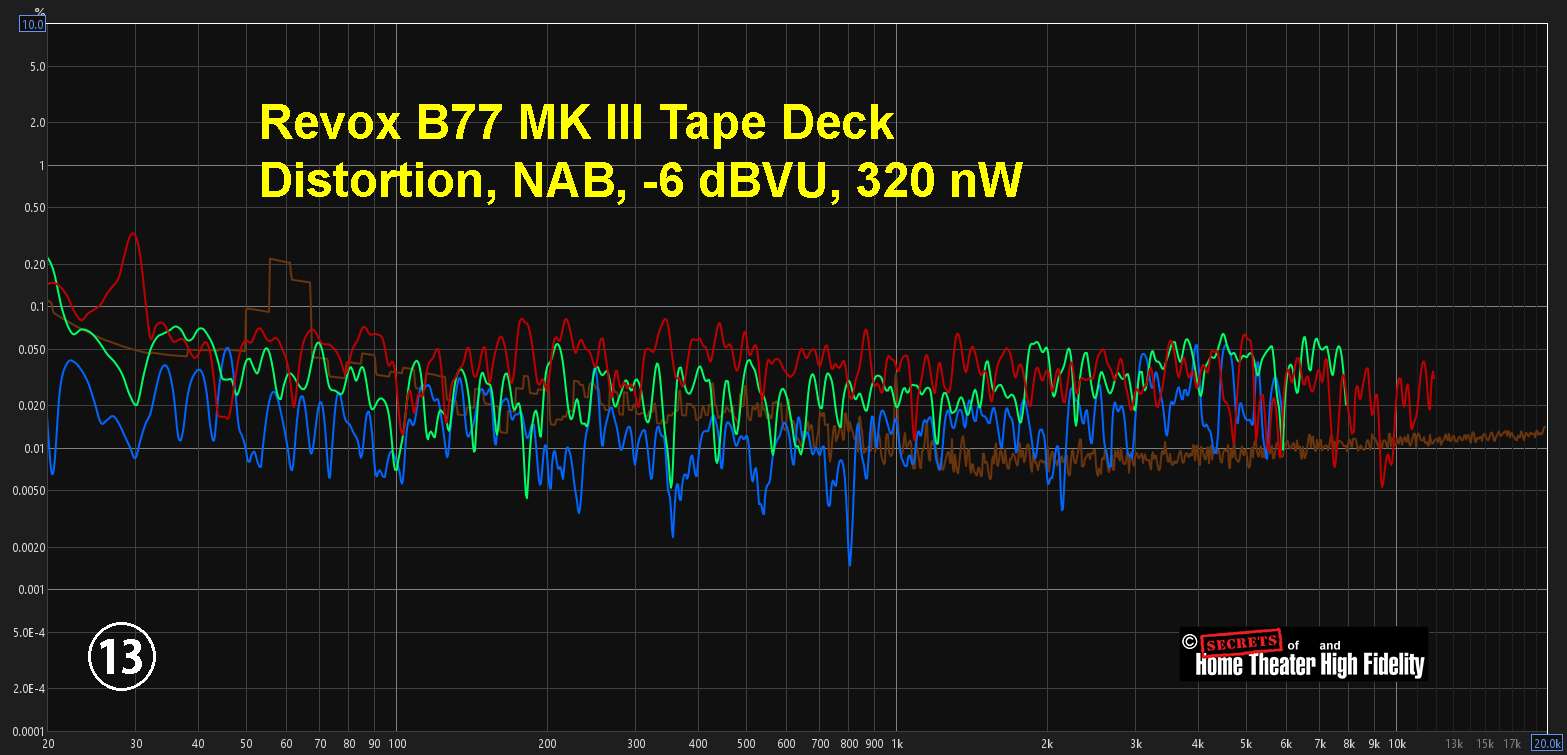

Figure 13 illustrates the same test but with NAB EQ. 2nd-ordered harmonics are a bit higher than at CCIR EQ.

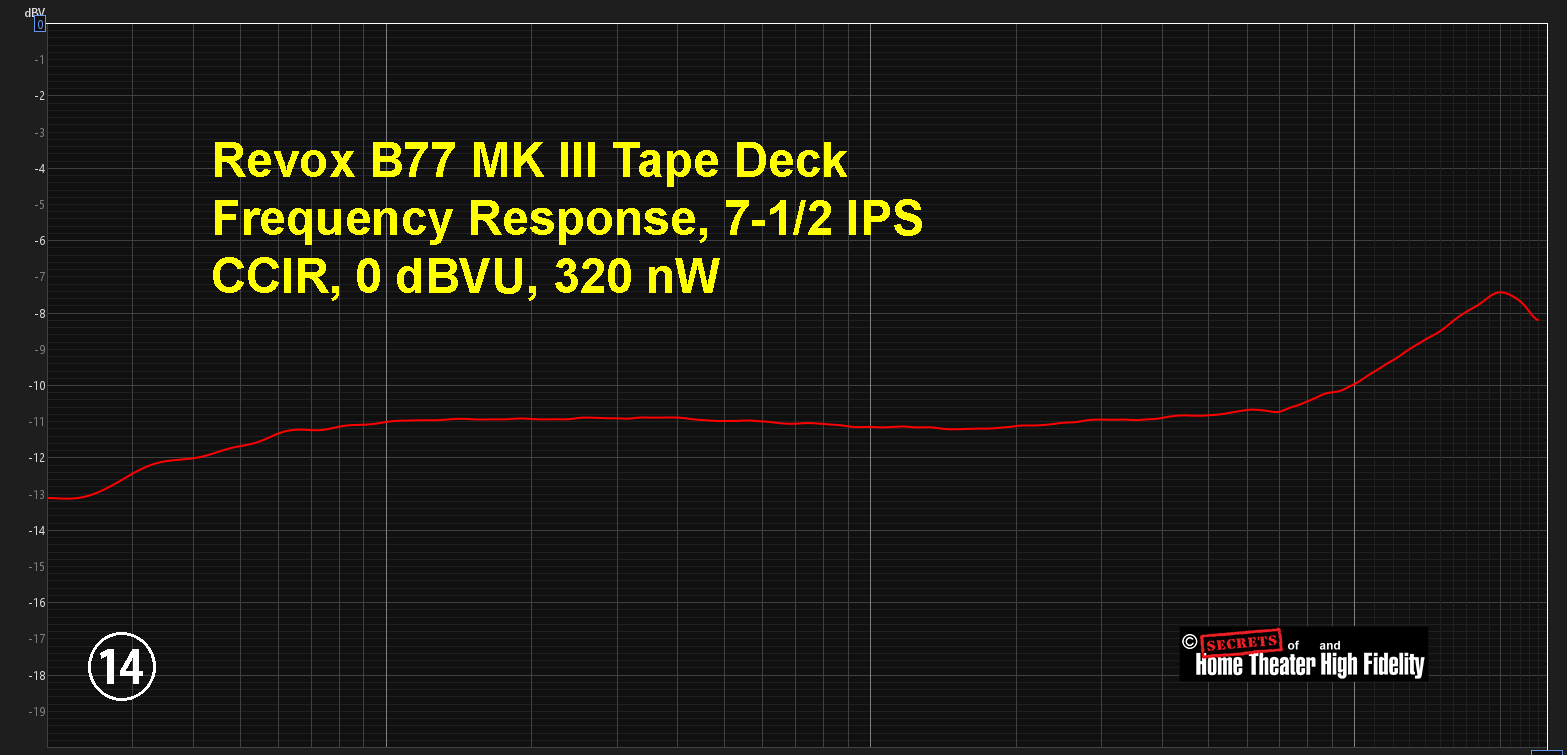

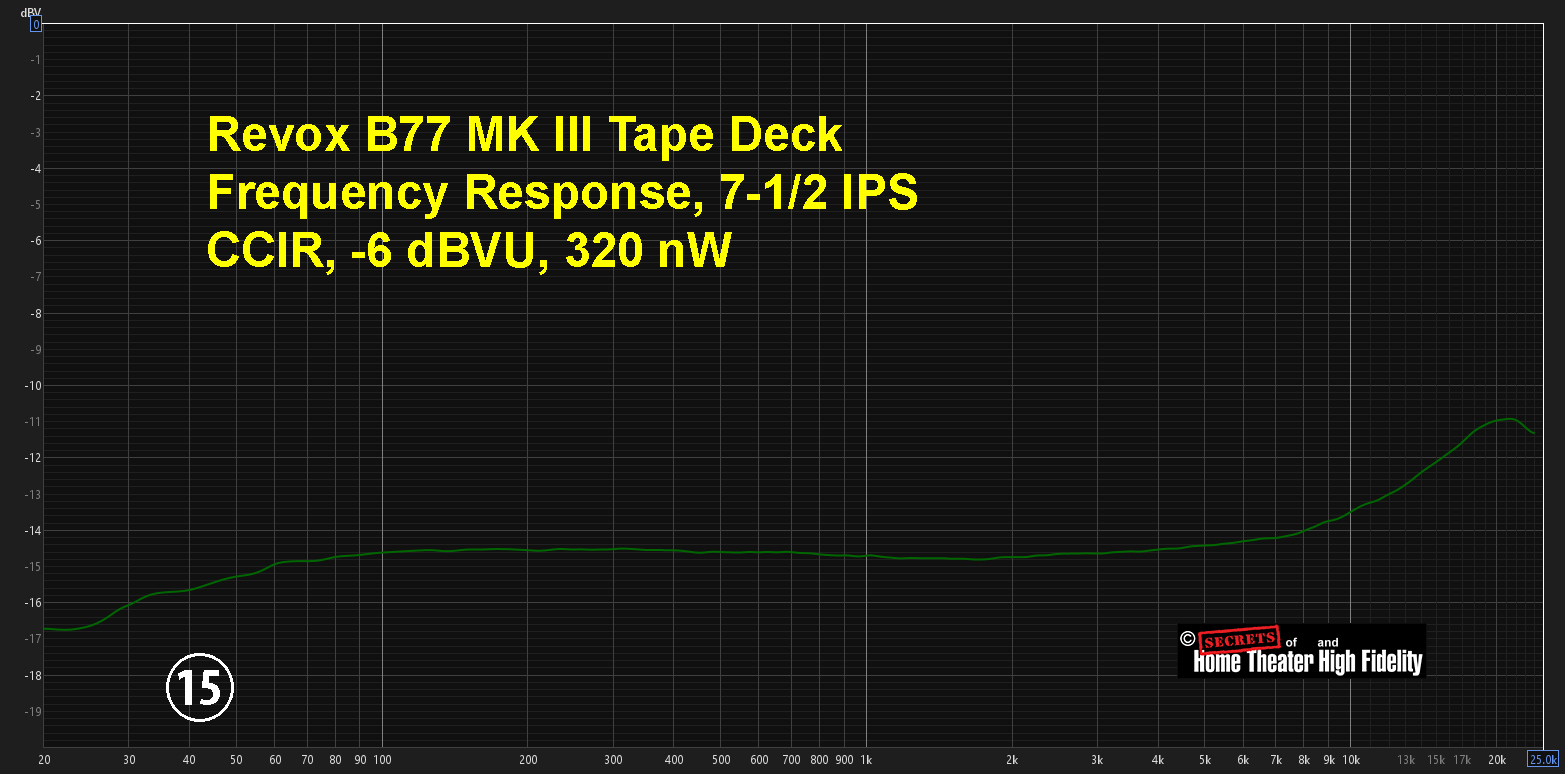

The Frequency Response at 7-1/2 IPS is shown below, CCIR, 0 dBVU. It is quite a bit different than at 15 IPS.

And, at -6 dBVU, about the same.

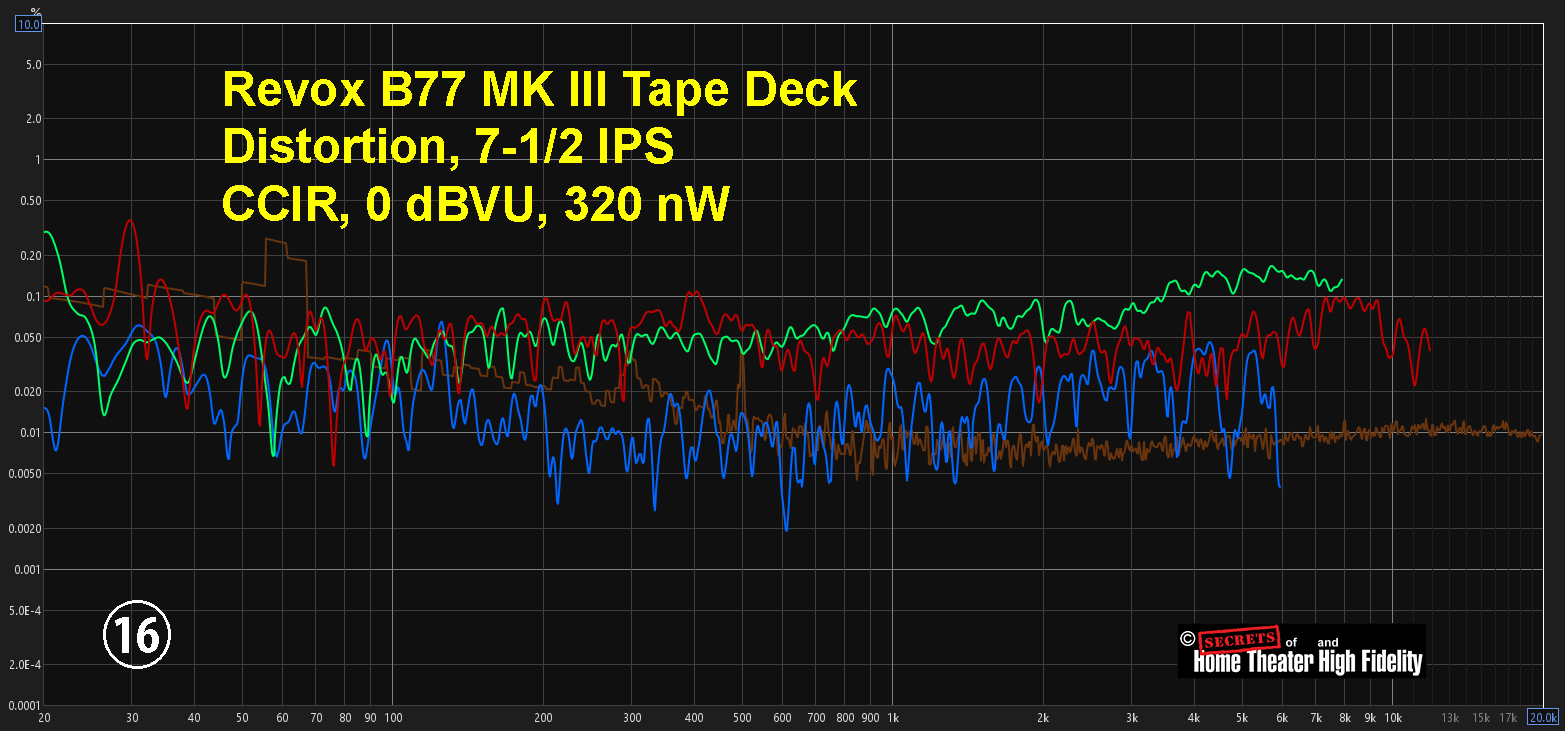

Distortion at 7-1/2 IPS and 0 dBVU is shown below, in Figure 16. It’s about the same as at 15 IPS.

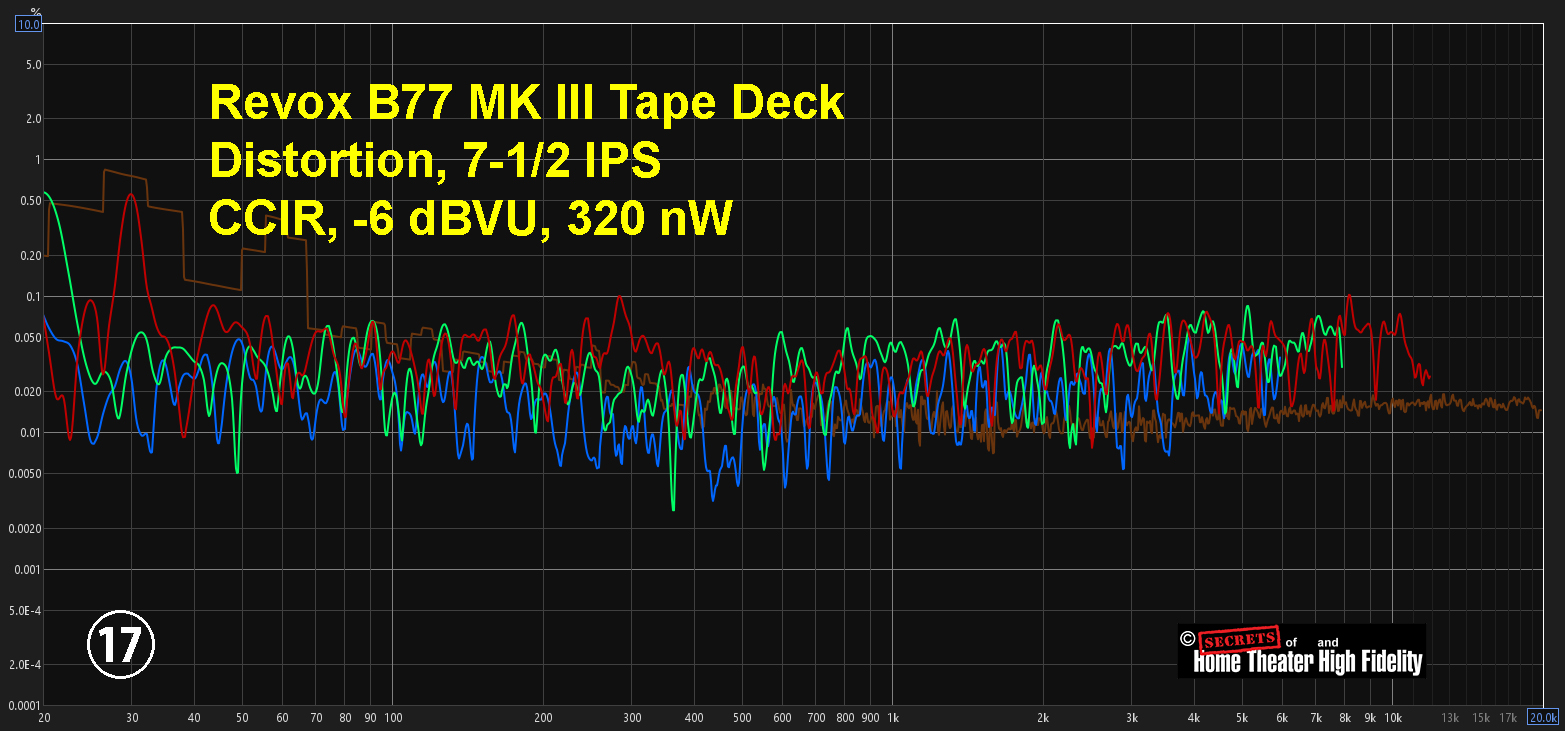

And at -6 dBVU. So, the amount of distortion does not change between 15 IPS and 7-1/2 IPS, but the frequency response certainly does.

Crosstalk was -57.5 dB, and Wow & Flutter was 0.06%.

For those pursuing the finest analog tape experience available today, the Revox B77 MK III is right in there with the best of them. A truly sublime audio experience.

- Terrific sound

- Very small playback head gap

- Film capacitors

- Smooth operation

- Backlit main functions button strip

- Larger digital counter

The Revox B77 MK III tape deck is a masterpiece of analog audio engineering, representing the pinnacle of what reel-to-reel technology can achieve in the modern era. At nearly $20,000, this is not a casual purchase; it is a statement of commitment to analog recording and playback at the highest level.

The engineering choices Revox made reflect a deep understanding of tape physics. The 0.25-micron playback head gap pushes high-frequency response far beyond audible limits, while the 125 kHz bias frequency ensures clean recording with minimal intermodulation artifacts. The choice between 320 and 510 nWb/m flux settings accommodates both vintage tape stock and modern high-output formulations, and selectable CCIR or NAB equalization provides compatibility with recordings from any era or region.

Bench measurements confirmed the deck’s excellence: frequency response within ±1.5 dB across the audible spectrum, low harmonic distortion dominated by benign even-order harmonics, crosstalk of -57.5 dB, and wow and flutter of just 0.06%. These numbers meet the published specifications.

More importantly, the listening sessions revealed what measurements cannot fully capture. Jazz recordings exhibited natural warmth, realistic transients, and that ineffable sense of presence that draws listeners into the performance. Electronic music lost its digital edge without sacrificing detail or dynamics. The B77 MK III delivers the sonic characteristics that have fueled the analog revival: smoothness, dimensionality, and musical engagement, while providing the reliability and precision that modern enthusiasts expect.