In 1970, the biggest tube TV you could buy was 25 inches. Or you could spend major money on a rear-projection model. These gave rise to CRT projectors which were also very expensive.

The invention of microdisplay technology, LCD, LCoS, and DLP, gave us digital projection where a relatively small box could, depending on lamp power and optics, project an image up to 300 inches diagonal.

Secrets Sponsor

The first digital projectors were powered by bright lamps, essentially fancy light bulbs, with a few different methods of producing light. Mercury vapor was and is still the most common way to achieve enough brightness to fill a large screen with a bright image.

In man’s never-ending search for a better way, the industry began experimenting with solid-state methods of producing light, lasers, and light-emitting diodes, better known as LEDs. Today, these are commonplace because they solve a few major issues that have always plagued lamp-based displays.

They last much longer for one. A lamp might go 3,000 hours but in practice, I’ve found enough reduction in brightness after 1,000 hours to motivate replacement. And that usually costs between $200 and $400 each time. Plus, that lamp dims slowly over that time. LEDs and lasers don’t last forever but today’s examples are rated for at least 20,000 hours. If you do the math versus a lamp, say 2,000 hours for the sake of argument, that’s ten lamps or $2,000 to $4,000. In other words, you’ll have paid for a second projector in those 20,000 hours.

If you do a quick search at this writing, June 2024, you’ll find that all the major projector makers have filled their lines with laser and LED models, to the point where lamps only exist in the less expensive products.

So, why is this important? Why do you want a laser or LED projector? Let’s take a look.

How Laser Projectors Work

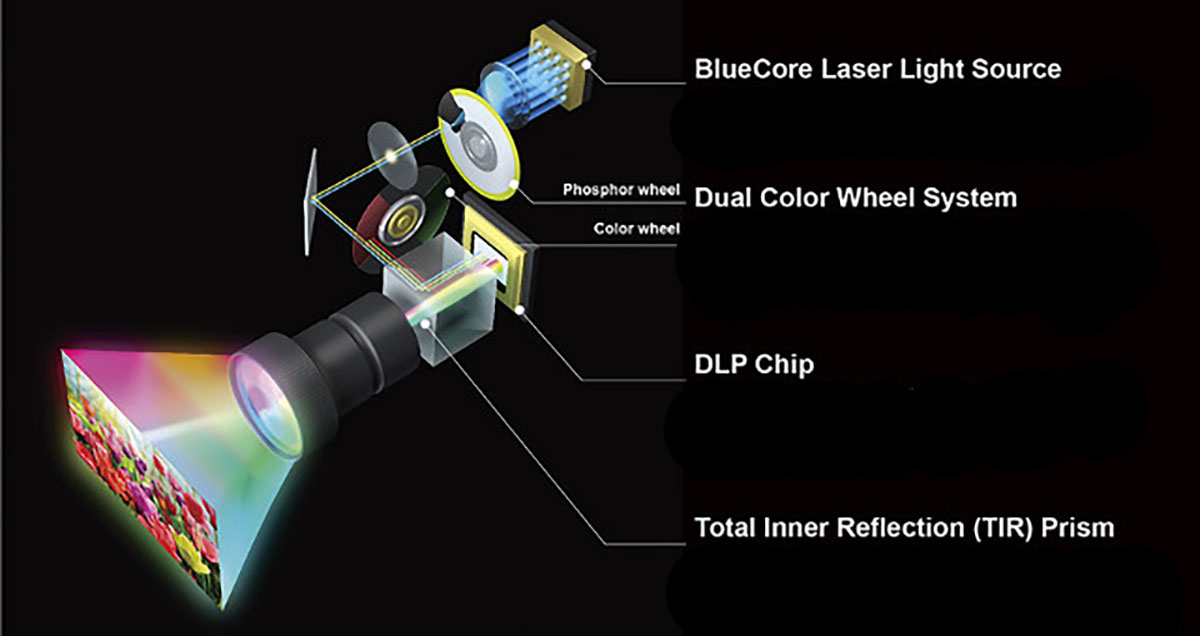

I’ve written on this subject before. 10 years ago, I talked about laser projectors in a technical article which you can read here. The principles haven’t changed in those 10 years. The most popular variant seen today is the single blue laser. If you see a laser projector selling for less than $3,000, it is likely a single laser model. A blue laser is focused on a phosphor wheel that spreads its light over the imaging chip. If there are three chips like in LCoS and LCD, prisms are used to direct the light. Single-chip DLPs can most easily use this tech and you’ll find this engine in many compact displays including ultra-short throw examples.

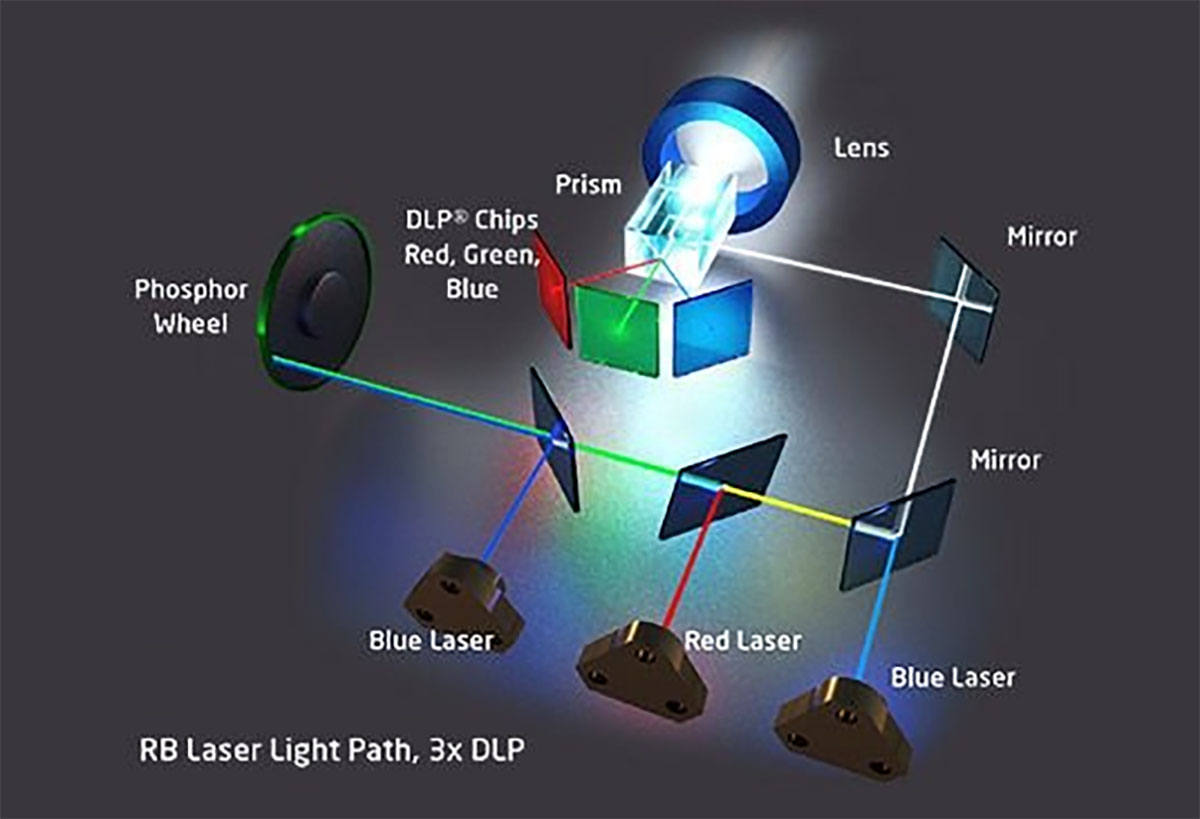

Moving up the price line, you’ll find tri-laser models. Their advantages are greater light output and larger color gamuts. They also cost more but as more of them appear, prices fall. If you want to check out some direct comparisons of single and tri-laser projectors, I covered UST projector shootouts hosted by Projector Central in 2022 and 2023. I also reviewed BenQ’s newest laser model, the W5800 which raised the bar for color gamut volume using just a single laser.

So, why don’t we just put lasers in every projector? They seem to have no downside, right? Sadly, they are expensive, relative to lamps and LEDs. You can buy a low-powered LED projector for less than $1,000. And many lamp projectors sell below $1,000 which makes them very attractive to institutions on tight budgets. Of course, if you do the math for lamp replacements, a laser might wind up costing the same or even less than a lamp when amortized over time. But there is something that might bridge the gap both in cost and performance, LEDs.

How LEDs Work

LED projectors are not new. They made a brief appearance in the home theater market about 15 years ago. Remember Runco? I reviewed their Q750i in 2010 which sold for $15,000 and though it looked amazing, it wasn’t very bright, at least not by today’s standards. It put out around 80 nits which is fine for a light-controlled theater and a 92-inch screen but not enough for today’s media rooms with ambient light and 150-inch screens.

LED is literally all around you in many products. Televisions and computer monitors rely on them exclusively. Where LCD panels of old were backlit by florescent tubes, today they have arrays of LEDs either at the edges of the screen or behind in a multi-zone arrangement with selective dimming. And this technology has grown by leaps and bounds. I recently tested a 32-inch computer monitor capable of 2,000 nits. And you’ll find more and more household lights powered by LED instead of hot incandescent bulbs. Even fluorescent tube fixtures have given way to LED strips.

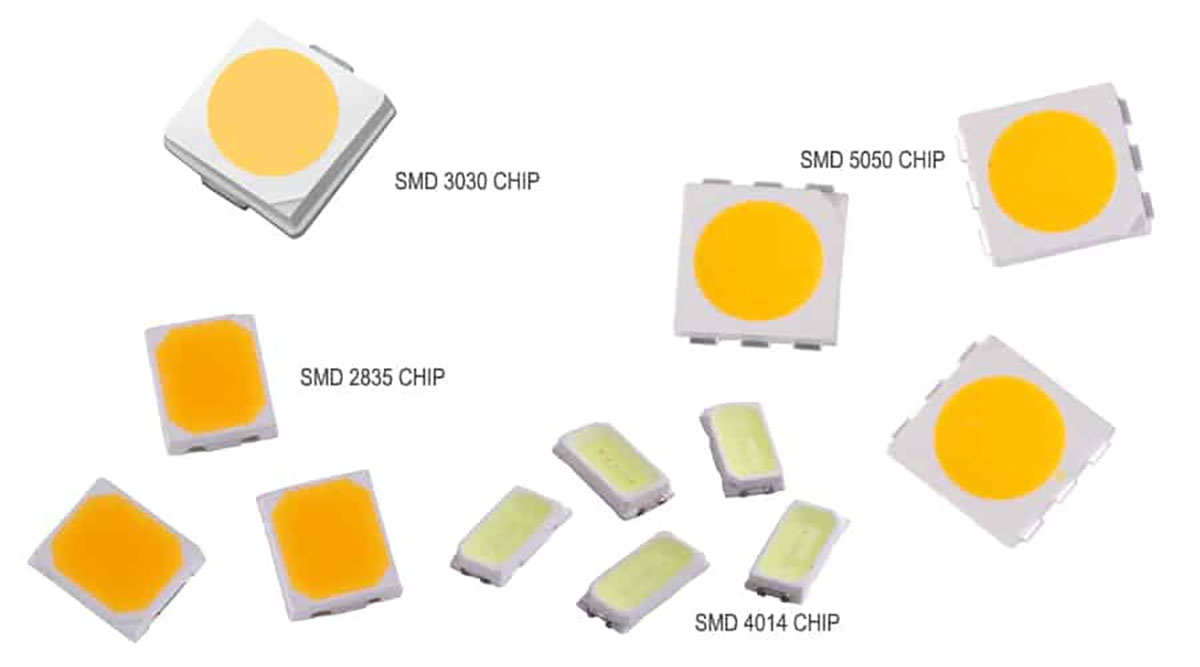

LED, or light-emitting diode, is a relatively simple technology. Two semiconductors, one positively charged and one negatively, emit photons from the movement of electrons between them. They are incredibly efficient in that they produce more light per watt than their filament-based predecessors while generating far less heat. The LED bulbs in my home are cool to the touch and their wattage consumption is expressed in single digits.

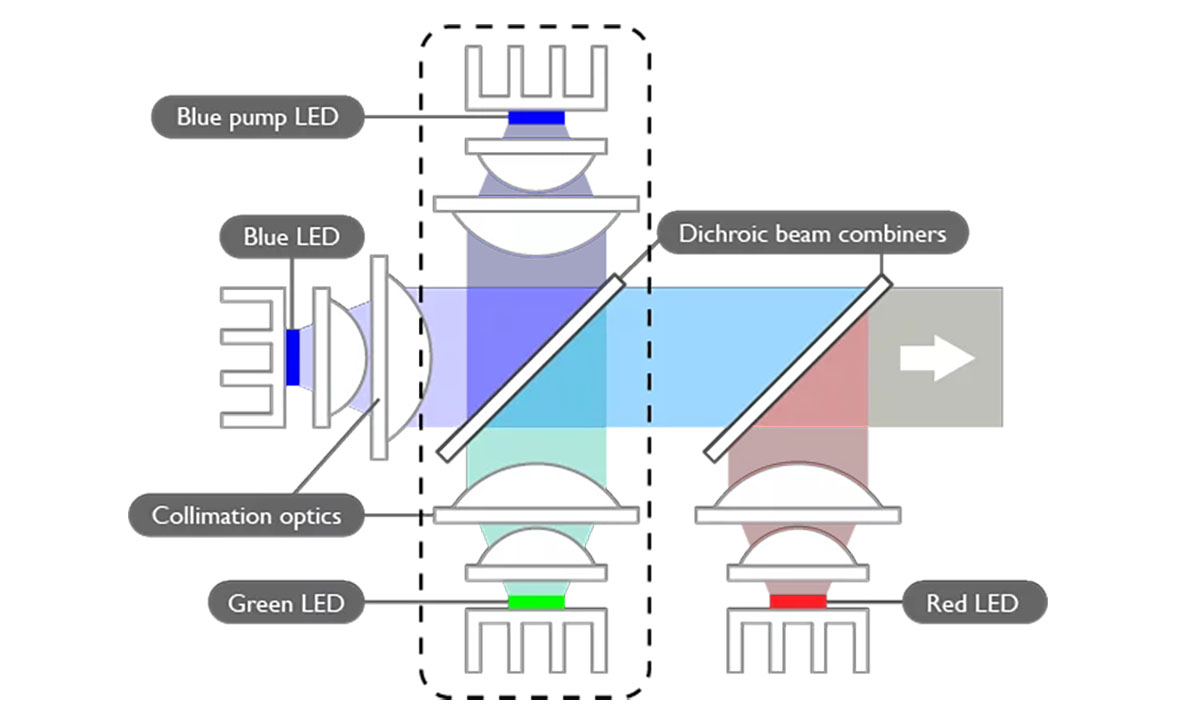

They are also very small which makes them ideal for compact projectors. And thanks to their abundance, they are less expensive than lasers. Check out my review of BenQ’s LH730 which sells for just $1,299. Or the home theater ready, $2,999 HT4550i. These are 4LED light engines, called such because they have four LEDs inside. BenQ uses red, green, and two blue diodes along with a single DLP imaging chip. Not only is this a cost-effective solution, but the projectors are compact and quiet.

Maintenance and Cleaning

This might be an unusual bit to discuss in a technical article but during my research, I learned a few things about projector care and service, particularly with regards to laser and LED models. If you’ve been part of the home theater hobby for long enough, you’ll remember the issue of dust in the light path of early LCD projectors, especially Panasonic which gained an unfortunate reputation for dust blobs back in the early 2000s. All projectors have some sort of particulate filter to keep the cooling air clean as it flows around the light source. Lamp projectors can’t seal in the bulb because it would quickly melt the innards of the display. But lasers and LEDs with their lower heat output can isolate themselves from dust. BenQ seals all the light sources in its LED and laser projectors. Even though they have fans, the cooling air never comes in direct contact with the imaging chips or the laser/LED. Chalk up another nail in the lamp coffin.

Applications for LED and Laser Technology

Considering both laser and LED technologies, strong cases can be made for each. In other words, it’s wrong to say that one is better than the other. Lasers are generally brighter and operate at wavelengths better suited to wide color gamuts. Their light is more focused which means less is wasted inside the projector. But they are more expensive, not because of complexity or exotic materials or difficulty of manufacture, but due to economy of scale.

LEDs are compact and efficient. They produce a lot of light for a given power rating and run cool. Projectors with LEDs don’t need large fans or heatsinks which means they can be smaller, quieter, and cheaper. LEDs are literally everywhere. You’ll find them on nearly every television and computer monitor. They’re all over the latest automobiles, in the headlights, taillights, interior lights, and behind the dash. LED light bulbs and tubes are still a bit more expensive than their incandescent counterparts but since they last many times longer and draw less electricity, people are buying them in quantity. And that drives the price down.

How does this relate to projectors? The application will remain the driving force behind light source technology. Projectors have many uses not related to home theater like gaming, presentation, and multimedia display. I learned recently that golf simulators provide the largest demand for gaming projectors. They require a compact and bright projector mounted on the ceiling and capable of throwing a 12-foot image from a relatively short distance.

LEDs have made a new generation of portable projectors possible. The latest models are smaller than what is normally considered compact and some even run on battery power. I looked at two from BenQ that are no larger than a shoebox, the GV30 and GS50, back in 2021. They can run long enough on their internal batteries to get through an average-length movie with sound from their internal speakers. Projectors like this would not be possible with a traditional lamp.

Secrets Sponsor

Lasers will continue to be the tech of choice for home theater. I have watched this technology grow and improve to where it is now found in nearly every premium model and in many mid-priced and value projectors too. My recent review of the BenQ W5800 marked a turning point in that it was able to reproduce 100% of the DCI-P3 color gamut without an internal filter. This is a huge step because that means it can render some killer HDR. You get full-color coverage with no reduction in light output. It’s a premium model at $5,999 but with 2,600 lumens and full signal support, it’s less expensive than comparable projectors from Sony and JVC.

Does incandescent have a future?

Given current trends, I don’t believe we’ll be seeing lamps in consumer projectors for much longer. The price gap between LED and laser is shrinking for sure. It has already come down to where the cost of bulb replacements will make that type of projector cost more over its lifespan. And the smaller size and efficiency of lasers and LEDs hit the ever-important convenience factor. Who wouldn’t want a compact projector that’s quiet, cool, bright, and needs no maintenance?

And with the larger color gamuts afforded by lasers, these displays are perfect for showing the latest HDR formats with their high color saturation and need for high brightness.

Will LEDs replace lasers?

At this point in time, my opinion is that each technology will maintain its place in the market. Lasers will be the tech found in mid and high-priced home theater models and LEDs will anchor the value and compact displays. But I wouldn’t rule out the possibility that LEDs will eventually be bright enough to match the performance of lasers.

Will TVs replace projectors?

This is a question I am often asked in conjunction with my ultra-short throw projector reviews. USTs are frequently marketed as television replacements. Indeed, they can easily do this given their easy setup on a bench or table directly in front of the screen. With little effort, you can have a 100-inch image that is bright enough to stand up to some ambient room light.

But in recent years, flat panel TVs have gotten much less expensive. As I write this, it is possible to buy a Hisense 100-inch flat panel with zone dimming, HDR, and wide gamut color for $2,800. Holy smokes! I remember looking at Panasonic’s 100-inch plasmas at CEDIA back in the day, which sold for north of $100,000! UST projectors aren’t super expensive, but they aren’t cheap either. A good one can easily cost $3,000 with high-end models like Leica’s Cine 1 tickling the underside of $9,000. When you consider the economy of scale, TVs outsell projectors by a tremendous margin. They will inevitably continue to get bigger and cheaper.

Conclusion

Whether you consider it symbolically or literally, the future of projection is a bright one. Home theater screens larger than 100 inches will continue to be dominated by laser projectors thanks to their high light output, saturated color, and support for HDR formats. Gaming and media rooms will continue to benefit from LED projectors that are compact, efficient, and inexpensive. And it’s distinctly possible that the proliferation of LED products will drive that technology to a point where it matches or even exceeds what laser is capable of. And flat-panel TVs will get bigger and cheaper, simply because that’s what they’ve always done.

For those of you following along, keep your eye on LEDs as they find their way into more home theater projectors. If you are shopping for something portable or something for your game room, there are already many LED projectors that suit those convenience applications. If you want to equip a dedicated home cinema today, laser will afford you the most choices. And BenQ has proved that a single laser model can provide the same brightness and color saturation as a tri-laser display. That means prices will continue to fall, or at least you’ll get more performance for the same money.

I hope you’ve found value in this technology update, thanks for reading!