I can see the edges of the prosthetics and even some gauze on their faces as they try to fool the bad guys into thinking they are someone else.

Here is a shot of Rollin Hand (Martin Landau) in Season 1, Episode 2, made up to look like the dictator general in a fictional country south of Cuba. Look at his skin. The prosthetics for his chin and bags under his eyes are obvious. The edges of his hairline don’t look right, nor do the wrinkles on his neck.

In the early days of television, studio makeup was designed only to look good at the level of detail the cameras and broadcast standards could actually show.

Back then, TV resolution was low — for example, early U.S. black-and-white broadcasts were around 525 total scan lines (but only about 480 visible vertically), and the effective horizontal resolution could be as low as the equivalent of 230–300 “TV lines” across the screen. The result was soft focus, low contrast, and little fine detail compared to modern HD.

Because of that:

● Makeup could be less refined – Artists didn’t need to smooth every pore or match color perfectly, because the TV camera and TV in the homes couldn’t resolve it. The goal was more about enhancing contrast and defining facial features so they wouldn’t wash out on black-and-white CRTs.

● Different products for TV vs. film – Film stock, even in the 1930s–50s, could resolve far more detail than TV, so studios often had “TV makeup” that was heavier, less expensive, and sometimes even a different color tone than what would work for film.

● Colors didn’t matter much in B&W – For black-and-white TV, the shade of makeup mattered more than the hue. Red lipstick, for example, might photograph almost black, so makeup artists picked tones that translated well in grayscale.

● Stage lighting + cameras dictated choices – Cameras of that era had limited dynamic range, so makeup helped prevent skin from appearing too shiny or features from vanishing under bright studio lights.

Once higher-resolution color TV appeared in the late 1960s and 70s, makeup had to become more subtle and natural, because viewers could now see more texture, color mismatches, and brush marks. That’s also when HD eventually made “airbrushed” and “high-definition” makeup common in the industry.

The original Mission: Impossible TV series (1966–1973) is a perfect example of how makeup in that era was tailored to the resolution and broadcast technology of the time — in this case, U.S. NTSC color television, which had:

● 525 total scan lines (about 480 visible)

● Effective horizontal resolution roughly 330 TV lines — far softer than even today’s 480p SD video.

● Analog color encoding that softened detail even more and could shift hues slightly.

For Mission: Impossible, specifically:

1. Makeup was designed for “TV distance”

● The actors were heavily powdered to reduce shine from the hot tungsten studio lights and location lighting.

● Foundation shades were chosen to look natural through NTSC cameras, which had a limited ability to capture subtle skin tone differences.

● Because the resolution was low, fine blending wasn’t as important. Edges could be slightly rough without being visible to the audience.

2. Color and contrast were tuned for the cameras

● The series was shot on 35mm film for image quality, but it was mastered for TV broadcast, meaning fine film detail was lost in transmission.

● Makeup artists used stronger contrasts for eyes, eyebrows, and lips so facial expressions wouldn’t wash out when down-converted to NTSC.

● Colors were sometimes exaggerated on set, so they’d appear correct on a home TV.

3. Prosthetic disguise makeup could be simpler

● Mission: Impossible’s famous latex masks and prosthetics (applied to actors to impersonate others) didn’t need movie-level realism.

● At 1960s broadcast resolution, a carefully painted latex appliance could look flawless even if, in person, it was obvious up close.

● The production often relied on “cutaways” and lighting tricks to sell the mask illusion, taking advantage of the fact that TV viewers wouldn’t see tiny seams or texture differences.

4. Lighting did half the job

● Cinematographer camera tests ensured makeup would photograph well. Many disguises were shown under shadow or with controlled highlights to hide edges.

● Studio lighting was warm and directional, creating contrast that TV sets of the time translated into a pleasing image without revealing too much detail.

If you saw Mission: Impossible in a modern HD remaster, the disguises sometimes look more obvious. Seams, skin texture mismatches, and heavy powdering are visible that 1960s TV audiences never noticed.

Mission: Impossible’s “mask gag” is one of those 1960s TV magic tricks that worked brilliantly because of the technical limits of the medium.

How the masks were actually made:

The production used a mix of custom prosthetic appliances and full-head pull-over masks, but not the hyper-real silicone pieces you see today.

- Design and Sculpting

- A life cast (plaster mold) of the actor’s head was made.

- A sculptor created the target face (the “person” the agent would impersonate) in clay over the life cast, exaggerating or minimizing features as needed.

- Details like wrinkles, pores, and hairlines were often simplified. There was no need to capture pore-level realism for NTSC.

- Molding and Casting

- The clay sculpture was molded and then cast in foam latex – the same material used for movie prosthetics of the time.

- Foam latex was light, flexible, and paintable, but it had a visible matte texture that modern HD would pick up instantly.

- In some cases, they made thin slip masks (just the face area) instead of full heads, depending on the shot.

- Painting

- Painted with rubber cement paints or greasepaint, often in slightly exaggerated tones to survive NTSC color bleed.

- Subtle makeup effects like capillaries, skin mottling, or subdermal tones were skipped because they wouldn’t survive the broadcast compression.

- Hair and Eyebrows

- Hair was often part of the wig, glued to the mask edges if needed.

- Eyebrows could be painted on the latex or inserted as crepe hair. Either way, at NTSC resolution, they looked fine.

How they were applied on set:

● Fast changes: Often, the actor playing the “villain” would be the same actor playing the IMF agent wearing that villain’s face. The mask would be applied quickly over the IMF actor’s own skin (sometimes without blending edges perfectly) because the big “rip-off” moment was the money shot.

● Blending edges: Spirit gum or Pros-Aide adhesive was used to glue down the perimeter. Edges weren’t feathered into the skin like modern prosthetics. They’d just be hidden with lighting, framing, or costume collars.

● Cutaways for the removal:

- The famous “mask pull” was often a fake. They’d cut mid-action to a second take with the actor already in the other makeup, and use an over-the-shoulder or quick pull to hide the transition.

- In some cases, they used two masks – one loose “TV removal mask” for the shot, and one tight, realistic one for static close-ups.

Why it was “TV-convincing” in the 1960s

● Low resolution — NTSC’s ~330 horizontal lines meant edges, paint inconsistencies, and texture mismatches simply weren’t visible.

● Soft focus & diffusion — 1960s lenses often used diffusion filters or slight soft focus for glamour, further blurring edges.

● Broadcast artifacts — Color bleeding and mild ghosting hid small flaws.

● Lighting control — Masks were revealed under shadows, with strong key lighting only after the “switch.”

Why it wouldn’t pass muster in 4K

● Foam latex has a uniform matte texture that doesn’t match real skin’s fine detail and varied sheen. In 4K, it’s obvious.

● Edges of the appliance, which in NTSC were invisible, would be glaring in ultra-HD.

● Color matching between mask and real skin is far more critical with modern cameras; 1960s makeup painted for NTSC can look cartoonish in 4K.

● Hairlines, eyelashes, and pores are clearly fake without today’s silicone, hand-punched hair, and subdermal paint layers.

If you watch the Mission: Impossible Blu-ray remasters today, you can often spot:

● Slightly stiff facial movement in “disguise” shots

● Edges along the jaw or neck

● Painted-on eyebrow textures

● Mismatched skin reflectivity between mask and actor

But in 1967 on a 19-inch RCA console TV? It was pure magic.

Here’s exactly how the Mission: Impossible “mask rip-off” shots were pulled off in the 1966–1973 series.

The “Continuous Pull” Illusion

Almost none of them were truly one-take. They relied on split shots, substitutions, and camera blocking to sell the idea.

1. The setup

- Step A – Actor as the “impostor”

- The scene begins with the target character — for example, a foreign diplomat — played by that actor in normal makeup.

- This is actually the IMF agent (say, Rollin Hand) pretending to be that diplomat, but the audience doesn’t know yet.

- Step B – The disguised actor

- When it’s time for the reveal, the actor is replaced by the IMF cast member wearing a loose “pull-off” mask of the diplomat’s face.

- This mask is made thinner and larger than the close-up mask, so it can be yanked off quickly.

2. The cut-point trick

The mask removal is rarely a continuous action for both faces.

- The disguised IMF agent grabs the “face” at the chin or neck.

- Camera pans quickly, or the actor ducks out of the frame.

- Cut to a shot from as lightly different angle. Now the same IMF actor is wearing no mask but regular makeup as themselves, pulling away the loose “mask” in their hand.

- Start with the IMF actor in a mask glued at only a couple of points for easy release.

- They start peeling the mask.

- As their hand blocks the camera, the mask piece is replaced with a pre-shaped “rubber face” prop that’s floppier and looks like it just came off.

- This avoids showing the real latex piece peeling off skin (which was clunky).

- A close-up shows the mask removal starting, usually from behind the head.

- Cut to a reverse angle where the mask is already half-off and hanging loose.

- In that reverse shot, the actor is just themselves. No appliance blending is needed.

3. Lighting & focus tricks

● Backlight and shadow during the pull kept edges invisible.

● Soft focus lenses meant the mask edges blurred into the skin.

● Often, the moment of mask removal was shown in medium or wide shots, reserving close-ups for “before” and “after,” never the messy in-between.

4. Why this worked so well in the ’60s

● The human brain “filled in” the action. Audiences assumed they saw the whole pull even when there was a hidden cut.

● NTSC’s low resolution blurred any mismatched edges between mask and skin.

● The “mask” we saw in the actor’s hand post-removal was usually just a thin prop face, not the real prosthetic, so it looked impressively lifelike.

If you watch the HD remasters today, you’ll notice:

● The “face” in the actor’s hand is often thicker and more rubbery than a real mask would be.

● The skin around the actor’s jaw is suddenly smoother or a different color between shots.

● The lighting sometimes changes slightly at the cut, giving away the switch.

I also noticed that the male actors had some form of what looked like pink lipstick on, and their faces seemed to have been shaven very, very closely.

That was a combination of camera technology, lighting, and makeup conventions from the film-and-TV industry of the 1950s – 1970s, and Mission: Impossible in particular, still carried over a lot of the visual style from earlier Hollywood studio practice.

Secrets Sponsor

Why male actors wore lipstick (or at least tinted makeup)

- In the black-and-white era, natural lip color could look pale or even disappear under studio lights, so makeup artists used mauve, coral, or muted red lip tints to make the mouth visible.

- Even though Mission: Impossible was in color, the habit (and the need to counteract bright lights) persisted.

- 1960s NTSC color cameras sometimes desaturated skin tones under tungsten lighting, especially when actors were heavily powdered to reduce shine.

- A subtle lip tint helped restore the look of healthy color. Otherwise, lips could appear gray or the same tone as surrounding skin.

- With ~330 horizontal lines of resolution, facial features needed stronger definition to “read” at home.

- Eyebrows, eyes, and lips were all emphasized with makeup — not to look glamorous, but to make expressions visible.

- Usually, it was greasepaint or cream makeup one or two shades darker than the actor’s skin, then blotted so it looked natural in person but photographed as normal lip tone on TV.

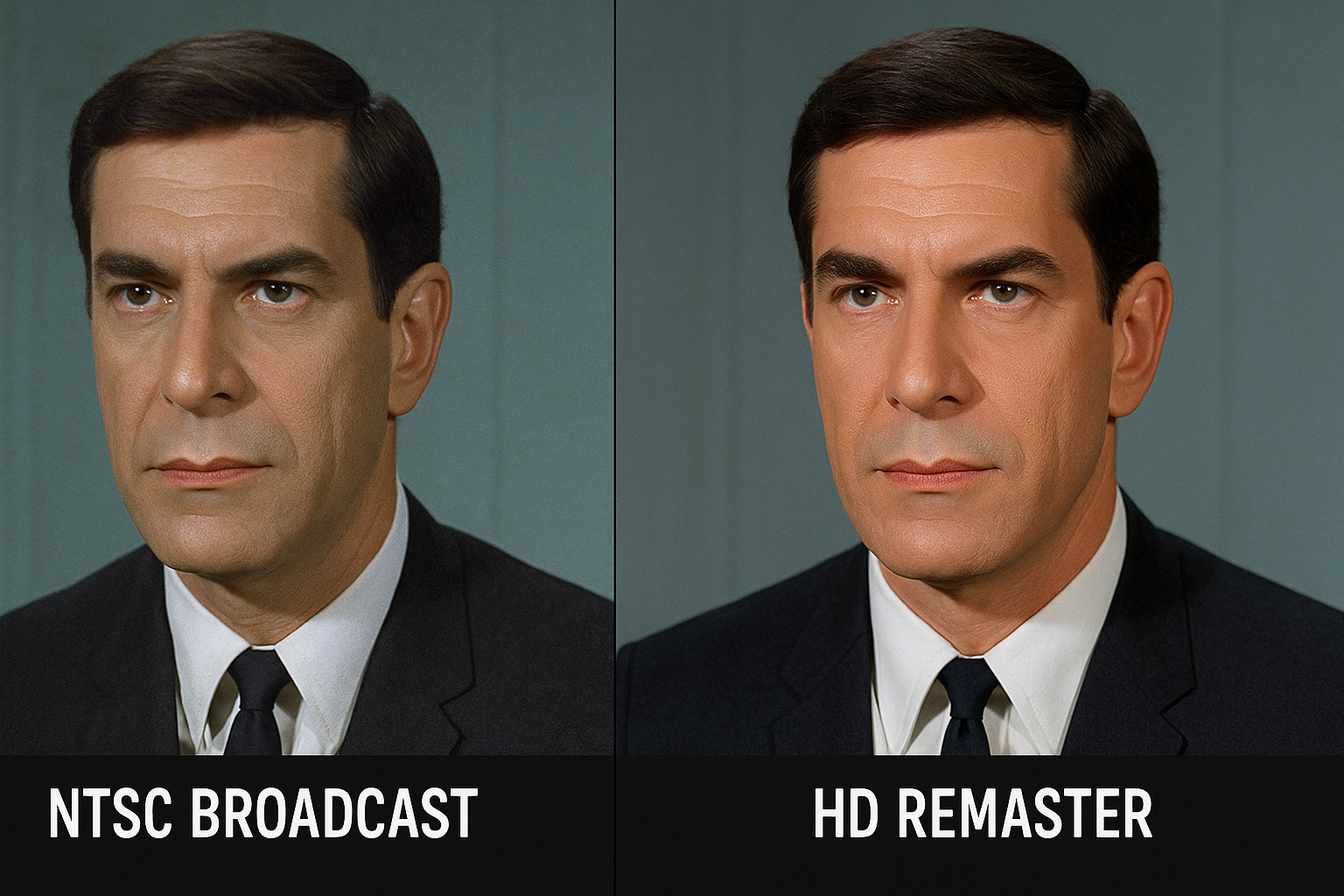

Here is a simulation of an actor’s headshot and how it would have appeared on TV in the 1960s TV series vs. what the original film transfer would look like on a modern high-res HDTV.

The color saturation in Mission: Impossible episodes is very high, and on purpose, and partly a byproduct of 1960s color television technology.

1. Era of “Technicolor TV”

● By the mid-1960s, networks wanted color programming to “pop” on new RCA and Zenith color sets.

● CBS (which aired Mission: Impossible) pushed for shows with vivid primaries — strong reds, blues, and greens — so they’d stand out in TV stores and living rooms.

● Producers often leaned into this with bold costume colors and strong set design palettes.

2. Filming and Postproduction Choices

● The series was shot on 35 mm Eastmancolor film, not videotape, which naturally allowed higher saturation than live studio shows.

● Cinematographers often overexposed slightly and used contrasty lighting to make colors appear brighter once transferred for NTSC broadcast.

● Color timing in post leaned toward warm, saturated tones so that skin tones wouldn’t look washed out on consumer TVs.

3. NTSC Broadcast Limitations

● The NTSC color system in the 1960s had a narrow color gamut and tended to desaturate subtle hues.

● To counteract this, shows like Mission: Impossible boosted saturation at the film and print stage, so that after broadcast, the image still looked lively.

● On today’s HD remasters, we see that the original boosted color without NTSC’s dampening, so it looks even more saturated than audiences remembered.

4. Visual Style of the Show

● Mission: Impossible used color contrast to tell the story — villains often wore bold colors, IMF disguises used striking makeup, and sets featured saturated reds/blues to heighten tension.

● Barbara Bain’s costumes, especially, were chosen in strong jewel tones that “read” clearly under studio lights and NTSC broadcast.

Color Saturation Chain

- Camera Negative (35mm Eastmancolor)

- Captured vivid color, strong primaries, but required lots of light.

- Interpositive (timed for exposure)

- A low-contrast copy from the negative; cinematographers and lab color timers adjusted brightness.

- Internegative (color correction applied)

- Here, the saturation was deliberately boosted to counter NTSC desaturation.

- Release Print (for TV syndication)

- Delivered with higher-than-natural saturation so it would still “pop” on color TVs.

- NTSC Broadcast (1960s)

- The signal softened, smeared, and desaturated colors — but viewers at home still saw vivid tones.

- Modern HD Scans (Blu-ray/4K remasters)

- Now we see the original boosted saturation directly from the film, without NTSC loss — which is why the show looks even more colorful today.

Bottom line: The bold, almost glowing colors in Mission: Impossible weren’t an accident — they were the result of careful choices in film stock, lighting, and color timing, all done to fight the limitations of NTSC broadcast. Today’s remasters reveal the full intensity of what was baked into the film prints.

So, the high saturation was partly on purpose (to make CBS’s color broadcasts “pop”), and partly a technical necessity (to survive NTSC’s limited color fidelity). Modern Blu-rays reveal those boosted colors more strongly than 1960s viewers actually saw.

Why male actors’ skin looked freshly shaved:

- Heavy key lights threw shadows that could exaggerate any stubble into dark patches on low-res cameras.

- Daily close shaves (sometimes twice a day on long shoots) kept faces evenly lit and free from shadow “noise.”

- Pancake foundation or cream makeup adhered much better to completely smooth skin. Even light stubble could make makeup look blotchy on camera.

- Mission: Impossible was shot on 35mm film, which could capture more detail than broadcast TV could show. Without a clean shave, stubble would still be visible in production stills, promos, and later reruns.

- 1960s network TV often wanted leading men to project a polished, well-groomed appearance – part of the era’s visual language. Even the “tough” characters had immaculate grooming. However, I did notice this even on the bad guys.

The net effect on screen:

On a 19-inch 1967 color console TV:

● The slightly darker lip color just looked like normal, healthy lips.

● The super-close shave avoided “shimmering” dark patches where stubble might have caught the light.

● Combined with powder to kill shine and contour to define cheekbones, it made faces read clearly despite NTSC’s fuzziness.

On today’s HD remasters, you can spot:

● The lip tint, especially in close-ups.

● Skin texture that’s unusually smooth for an unshaven man, sometimes to the point of looking like mannequin skin.

That “greasy, shiny” look you sometimes see on actors’ faces in the original Mission: Impossible series is a combination of lighting technology, makeup materials, and the limitations of 1960s color TV cameras — and in some cases, it was actually intentional.

1. Hot studio lighting

● In the 1960s, TV productions used tungsten quartz-halogen lights (2K “Moles” and similar) to get enough exposure for film cameras.

● Sets were often lit to 200–300 footcandles — extremely bright compared to modern shoots — so the cameras could use smaller apertures for depth of field.

● Under these lights, even slightly oily skin would reflect and look shiny.

● Sweat from the heat built up quickly during takes, especially under makeup or wigs.

2. Makeup formulas of the era

● Most TV makeup then was oil-based greasepaint or early cream stick foundation, not today’s silicone-based HD makeup.

● Greasepaint gives good coverage and blends easily, but it has a natural sheen — even with powder, it can look shiny under strong key lights.

● Color TV made this worse: NTSC cameras exaggerated highlights, so any reflective area popped more than it would in person.

● For male actors, powder was used sparingly to avoid a chalky look, so their skin often appeared shinier than their female co-stars’.

3. Color TV camera limitations

● Mission: Impossible was shot on 35 mm film, but lighting and makeup were chosen with NTSC broadcast in mind.

● NTSC color encoding in the ’60s tended to flatten midtones but exaggerate contrast in highlights, making shine look stronger than it was on the film negative.

● When these shows are remastered in HD today, the original sheen becomes even more obvious because we’re seeing the uncompressed film scan.

4. Intentional “sweat” for dramatic effect

● In tense close-up scenes, especially in disguise or interrogation sequences, makeup artists sometimes deliberately left a sheen or even added glycerin to simulate stress perspiration.

● A little forehead shine helped sell that a character was nervous, hot, or under pressure — and on low-res 1960s TV, it read as “realistic” rather than “oily.”

Why it’s more noticeable now

On a 19-inch 1967 RCA color console, the NTSC signal’s softness blurred a lot of this, so the actors didn’t look overly greasy at home. In modern Blu-ray remasters, the film’s true resolution reveals:

● The actual texture of oil-based makeup.

● Beads of sweat that were invisible in the original broadcast.

● Uneven powder application or shine on the nose, cheeks, and forehead.

Why Mission: Impossible didn’t simply powder everyone more heavily — it’s actually a trade-off they made because of how powder looked worse than shine on 1960s color TV. That choice is part of why faces sometimes glisten in the show.

Some of the plots feel thin or “superficial” compared to the intricate premise — and that wasn’t accidental. It had a lot to do with production economics, TV audience expectations, and stylistic choices of the era.

1. Budget and Scheduling Pressures

● A one-hour network drama in the 1960s had to turn out 24–26 episodes per season, on a tight weekly production schedule.

● Writing deeply layered plots for every episode was difficult; producers often relied on formulaic story structures (mission briefing → setup → infiltration → reveal → escape).

● By keeping some plots simple, the production team could devote more resources to:

- Elaborate sets and disguises

- Stunts and visual spectacle

- The rich color cinematography, CBS prized for selling color TVs

2. Color as a Selling Point

● CBS (and sponsor RCA for NBC) was heavily invested in promoting color television in the late ’60s.

● Producers knew audiences were dazzled as much by how shows looked as by story depth.

● Mission: Impossible leaned into bold visual design — jewel-toned costumes, saturated lighting, exotic sets — to give viewers a sense of high style, even if the plot itself was straightforward.

3. Audience Experience

● 1960s TV was not “binge-watched” — each episode had to be self-contained and understandable to a casual viewer.

● The superficiality of some plots was intentional: they functioned as a framework for tension and spectacle, not complex psychological drama.

● The emphasis was on the process (gadgets, masks, deceptions, reversals) rather than on deep character arcs or moral dilemmas.

4. Comparison to Later Spy Dramas

● Unlike The Prisoner (UK, 1967–68), which explored philosophy and identity, Mission: Impossible was designed more like a weekly puzzle box with a clear beginning and end.

● It was closer to a heist show than a character-driven drama — precision, style, and suspense mattered more than layered storytelling.

So, some episodes had superficial plots by design — it saved money, made production faster, and foregrounded what CBS and Desilu really wanted audiences to notice: the color-saturated visuals, exotic disguises, and ingenious IMF tricks that made the series stand out.

Speaking of image sharpness, quite a few TV series in the “old days” were shot on 16 mm film rather than 35mm film, especially in the 1950s through the 1970s.

Whether a show used 35 mm or 16 mm usually came down to budget, location needs, and intended broadcast quality.

Why 16 mm was used

● Lower cost — 16 mm film stock, processing, and camera rentals were much cheaper than 35 mm.

● Portable equipment — 16 mm cameras were smaller and easier to use for location shooting or handheld work.

● Syndication and news — Many series aimed for daytime slots or local syndication, where the resolution advantage of 35 mm wouldn’t be noticed much on NTSC TV.

● Documentary style — Some shows wanted the slightly grainier, less “polished” look of 16 mm.

Examples of TV series shot on 16 mm.

● Early Doctor Who (BBC, 1960s) — Studio scenes on videotape, but all location footage was shot on 16 mm.

● MAS*H — Entire series shot on 16 mm to keep costs down; still looks pretty sharp in HD because of good lenses and lighting.

● The Rockford Files — Many exterior and chase scenes on 16 mm for portability, mixed with 35 mm studio shots.

● News and documentary shows — 60 Minutes, early Wild Kingdom, and many PBS dramas used 16 mm extensively.

Secrets Sponsor

Drawbacks in the HD era

When remastered from the original camera negatives, good 16 mm can still look decent in HD, but:

● It has more visible grain than 35 mm.

● Fine detail is lower, especially if the show was edited from 16 mm release prints instead of negatives.

● Optical effects (titles, dissolves) done on 16 mm stock often look softer.

Here’s a list of notable U.S. prime-time dramas from the 1960s and 1970s that were shot entirely on 16 mm film — not just location inserts, but the whole show.

Prime-Time Dramas of the 1970s and 1980s Shot Entirely on 16 mm

(Alphabetical, with years of original broadcast)

● Adam-12 (1968–1975, NBC) – Police procedural from Jack Webb’s Mark VII Limited; used 16 mm for mobility during on-location patrol scenes and kept it for all production.

● Emergency! (1972–1979, NBC) – Same production team as Adam-12; shot in 16 mm for faster field shooting with fire trucks, ambulances, and hospital sets.

● Kung Fu (1972–1975, ABC) – Entirely 16 mm, chosen for a softer, more “period” look and easier shooting in outdoor locations and old western towns.

● Little House on the Prairie (1974–1983, NBC) – One of the longest-running prime-time dramas shot entirely on 16 mm; filmed outdoors on the Simi Valley set with Arriflex cameras.

● MAS*H (1968–1975, NBC) – (1972–1983, CBS) – Studio and exterior scenes all on 16 mm; Robert Altman’s original M*A*S*H film was 35 mm, but the series switched for budget and speed.

● The Six Million Dollar Man (1973–1978, ABC) – 16 mm Panavision equipment kept action sequences flexible and cheaper; all principal photography was 16 mm.

● The Waltons (1972–1981, CBS) – Entire series on 16 mm; heavy outdoor shooting in rural locations drove the choice.

● Wonder Woman (Season 1, 1975–1977, ABC) – All first-season episodes were shot on 16 mm; switched to 35 mm for the later CBS seasons for a glossier look.

Why most “prestige” shows still used 35 mm

While 16 mm was common for outdoor, action, and lower-budget series, most high-budget dramas and crime procedurals (Mission: Impossible, Hawaii Five-O, Columbo, etc.) stayed with 35 mm for sharper images and better color reproduction. Networks knew those shows would rerun for years, and 35 mm preserved more detail.

In the 1950s, 16 mm film was used far less often for prime-time scripted series than in later decades, but it did show up — mostly in lower-budget, location-heavy, or syndicated productions. Networks and big studios generally preferred 35 mm for image quality, but smaller outfits used 16 mm to save money

Here’s a list of notable U.S. prime-time or first-run syndicated series from the 1950s shot primarily on 16 mm film:

Westerns and Action Shows

● The Adventures of Kit Carson (1951–1955, syndication) – Low-budget Western filmed entirely on 16 mm for location flexibility.

● The Cisco Kid (1950–1956, syndication) – Famous as the first U.S. TV series filmed in color; shot on 16 mm Kodachrome to save costs.

● Sky King (1951–1959, syndication) – Aviation adventure series; filmed on 16 mm to allow portable camera work on airfields.

● Ramar of the Jungle (1952–1954, syndication) – Jungle adventure series shot in 16 mm for on-location portability in California and Florida, standing in for Africa.

● The Lone Ranger (early seasons in the late ’40s on 35 mm; later color episodes for 1950s syndication often done on 16 mm for economy).

Crime and Detective Shows

● Highway Patrol (1955–1959, syndication) – Broderick Crawford police drama filmed quickly on 16 mm for low-cost distribution to local stations.

● Sea Hunt (1958–1961, syndication) – Lloyd Bridges’ diving adventure; shot largely on 16 mm because of extensive underwater and location shooting.

Other Genres

● Captain Gallant of the Foreign Legion (1955–1957, syndication) – Filmed in Morocco; used 16 mm for transportability.

● Sheena, Queen of the Jungle (1958–1961, syndication) (1955–1956, syndication) – Entirely on 16 mm; filmed in Florida swamps with portable gear.

● Fury (1955–1960, NBC) – Western/children’s drama; much of it shot outdoors on 16 mm for speed.

● The Adventures of Wild Bill Hickok (1951-1958, CBS) – The lower cost allowed for cranking out a very large number of episodes (over 100 in the first two years alone).

● Captain Midnight (1954-1956) – Filmed in 16 mm Eastman Color – Color filming was intended for “future-proofing” and for promotional purposes, even though it was down-converted to B&W for most 1950s broadcasts.

TV shows filmed in 16 mm still looked fine on 1950s TVs, where the resolution and NTSC limitations made 16 mm indistinguishable from 35 mm to most viewers.

For those of us who grew up with early television, we are now going back to see some of the shows that were shot with 35mm film, like Mission: Impossible and Gunsmoke, and seeing them for the first time in Blue-ray quality.