The design of audiophile-grade audio cables is a pursuit that combines science, engineering, and craftsmanship. At first glance, these cables might seem like simple conductors of electrical signals, but for those deeply committed to high-fidelity sound reproduction, they are the result of decades of experimentation, refinement, and innovation. From conductor geometry and shielding techniques to dielectric materials and termination quality, every detail of the design is carefully scrutinized to ensure signal integrity and reduce sources of distortion. Designers of high-end cables dedicate significant time and resources to make sure their products meet strict electrical performance standards—such as low capacitance, minimal resistance, and high resistance to electromagnetic interference—believing that even small differences can impact the musical experience.

Skeptics often ask whether such improvements offer noticeable benefits, especially since the human ear varies greatly in sensitivity, often affected by age, listening environment, or familiarity with sound details. However, for dedicated audiophiles, the goal isn’t necessarily a measurable improvement that everyone can notice, but rather the assurance that no part of the signal chain is compromised. Striving for perfection in audio reproduction means ensuring every link, including the cables, meets the highest standards. Even if the sonic differences are subtle or difficult to detect, the confidence gained from using carefully crafted components provides peace of mind and a feeling of completeness when listening. For many, this pursuit of excellence is driven as much by passion and pride as by the desire for better performance.

1. Conductors: The Heart of the Cable

The choice of conductor material can impact signal transmission and sound quality.

Common materials include:

● Oxygen-Free Copper (OFC): High-purity copper with minimal oxygen content, reducing resistance.

● Silver-Plated Copper (SPC): The Primary reason is that copper reacts with Teflon dielectric (see below).

● Pure Silver: Extremely conductive and often used in ultra-premium cables for maximum signal clarity.

● Litz Wire: A special type of braided or stranded wire to minimize skin effect and resistance at higher frequencies. However, it has increased capacitance – see below.

What is OFC really?

Oxygen-free copper is usually one of two grades:

● OFC / OFHC (C10200)

● Oxygen content: ≤ 0.001% (10 ppm)

● Purity: 99.95% copper

● Conductivity: ~100% IACS

● UP-OCC / “Ohno Continuous Cast.”

● Purity: claimed 99.999% (5N)

● Large grain size

● Marketed heavily in high-end audio

Standard electrical copper (ETP, C11000) is:

● Purity: 99.90%

● Oxygen content: 0.03% (300 ppm)

● Conductivity: ~100% IACS

So, the real difference in conductivity between ETP and OFC is:

Less than 0.5% (negligible in any audio-frequency application)

Does OFC have lower resistance?

Barely.

Here are the actual conductivity numbers:

| Copper Type | Conductivity (IACS) | Difference |

| ETP (Standard) | 100% | — |

| OFC | 100.3% | +0.3% |

| UP-OCC 5N | 101% (claimed) | +1% |

A typical 2 – 3-meter cable has milliohms of resistance.

A 0.3 – 1% reduction in resistance changes nothing audibly or measurably.

Does OFC improve sound quality?

No.

Not at audio frequencies, where:

● skin depth is large

● conductivity differences are tiny

● signal currents are extremely small

● cable losses are dominated by geometry, not copper chemistry

There is no measurable difference in:

● frequency response

● distortion

● noise

● phase

● crosstalk

● damping factor (beyond a fraction of a percent)

AES papers have repeatedly documented this.

What OFC is good for

The benefits of OFC are manufacturing and reliability, not audio performance:

Less oxide formation inside the wire

This matters for:

● high-temperature coils

● transformer windings

● motors

● electromagnets

Better long-term stability under heat

Not relevant in room-temperature audio interconnects.

Better ductility (slightly)

Useful for very fine wire (e.g., headphone cables).

Easier to draw into strands

Good for high-strand-count flexible cables.

These do not translate into better audio fidelity.

Marketing confusion: “Oxygen causes signal loss.”

Electrical resistivity of copper oxide is higher, but:

● copper oxide forms only on the surface

● contact surfaces are plated (typically gold or nickel)

● internal copper strands are insulated by PVC/PE/PTFE

● audio signals flow through the bulk metal, not the oxide layer

So, oxidation does not harm audio signals.

2. Dielectric Materials: Insulating the Signal

A high-quality dielectric (insulating material) reduces capacitance and signal degradation. Some of the best materials include:

● PTFE (Teflon): Low-loss and widely used in premium cables.

● Foamed Polyethylene (FPE): Lightweight and effective at minimizing signal distortion.

● Air-Tube Insulation: Air is the best dielectric, so some high-end cables incorporate air gaps to minimize interference.

3. Shielding: Blocking Unwanted Noise

Shielding protects the signal from electromagnetic interference (EMI) and radio frequency interference (RFI). Common shielding methods include:

● Braided Shielding: Provides strong interference protection and durability.

● Foil Shielding: Lightweight and effective for high-frequency noise rejection.

● Dual or Multi-Layer Shielding: Combines different shielding techniques for optimal noise suppression.

4. Geometry and Cable Construction

The way conductors are arranged inside the cable influences performance:

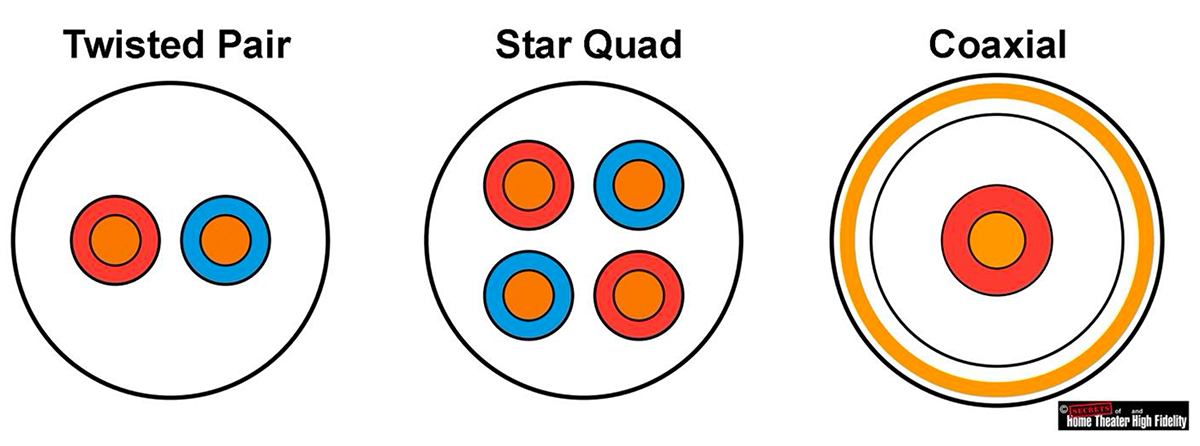

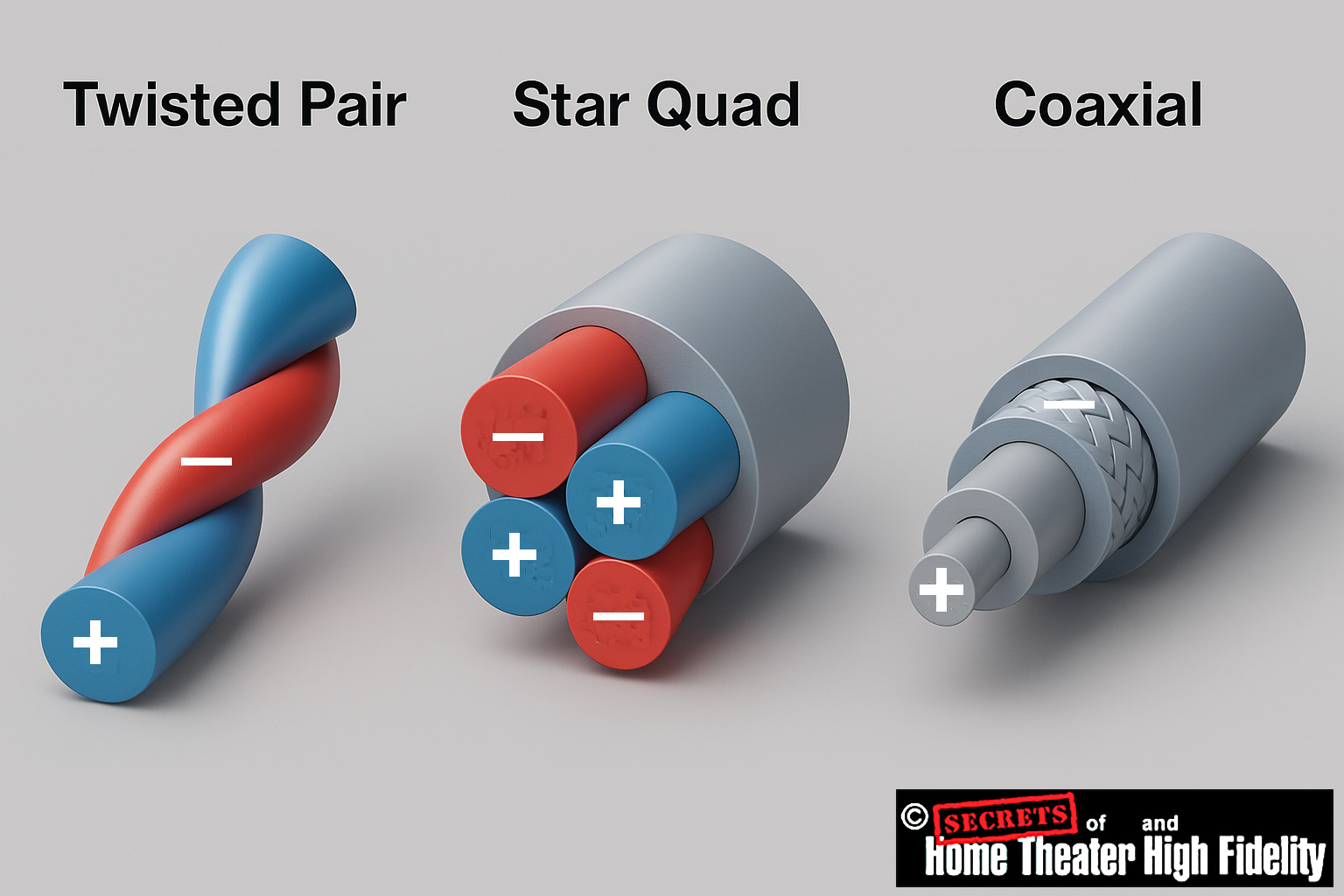

● Twisted Pair: Reduces electromagnetic interference by canceling out noise.

● Star Quad Configuration: Minimizes noise pickup and improves signal quality. It features four conductors arranged in a cross or square pattern, forming a quad structure. These conductors are twisted together precisely to ensure symmetrical performance. Opposing pairs of conductors are electrically connected to function as a single conductor. A shield, either braided or foil, usually surrounds the quad conductors for enhanced noise rejection. Advantages of Star Quad include: superior noise rejection, reduces EMI and RFI more effectively than standard twisted-pair cables; lower inductance, improves signal transmission, especially over long distances; better crosstalk protection, ideal for professional audio applications where clear signal transmission is crucial. Applications include: high-end microphone cables (e.g., Canare L-4E6S, Mogami 2534), professional audio setups, broadcasting studios, and occasionally, hi-fi speaker cables.

● Coaxial and Triaxial Designs: Used in specific applications where impedance consistency is crucial.

5. Connectors: The Gateway to the Audio Chain

High-quality connectors ensure a secure connection and minimal signal loss:

● Gold-Plated Connectors: Prevent oxidation and ensure consistent conductivity.

● Rhodium-Plated Connectors: More durable than gold and preferred in some premium cables.

● Cryogenically Treated Connectors: Some manufacturers freeze connectors in an attempt to enhance molecular structure and conductivity.

Does cryogenic treatment improve audio connectors?

Short answer:

Cryogenic treatment can improve the mechanical properties of some metals, but it does not improve conductivity or audio performance in any meaningful or measurable way for connectors.

What cryogenic treatment actually does (real science).

When certain metals or alloys are cooled to extremely low temperatures (typically – 300°F / –184°C):

Confirmed effects (materials science):

● Reduces internal stresses

● Can change crystalline structure in ferrous metals

● Improves wear resistance

● Improves hardness

● Can increase fatigue life

● Useful for: cutting tools, springs, knife blades, engine parts, brass instruments

Does NOT improve:

● Electrical conductivity

● Audio signal transfer

● Noise performance

● Contact resistance (beyond what gold plating already accomplishes)

Copper, silver, and gold (the metals used in audio connectors) do not gain measurable electrical performance from cryogenic treatment.

Even after cryogenic processing:

● Resistivity of copper is unchanged within measurement error

● The oxide behavior doesn’t change

● Contact plating behavior is unchanged

● Microhardness changes are irrelevant to audio connectors since they experience no stress cycles

Why do some cable makers claim benefits?

Marketing often attributes the following to cryo treatment:

● “Improved electron flow.”

● “Reduced molecular dislocations.”

● “Aligned grain boundaries.”

● “Lower resistance.”

● “Cleaner signal path.”

None of these effects occurs in copper, silver, or gold from cryo treatment at a level that influences AC audio signals.

In fact:

Grain-boundary alignment claims have been debunked repeatedly in metallurgy papers and by AES research.

AES, IEEE, and metallurgical consensus

Cryogenic processing does not produce measurable improvements in:

● DC resistance

● AC resistance

● Skin depth

● Contact impedance

● Noise

● EMI susceptibility

● THD

● Frequency response

The only performance parameter that might change is mechanical durability, and even that is negligible for connectors that are not under stress.

Why do some audiophiles report hearing differences?

● Expectation bias

● Different connectors or cable construction

● Different contact pressure from replugging

● Oxide layer removal due to reinsertion

● Different grip force or plating thickness

● Normal sample variance from one connector to another

None of these effects comes from cryogenic changes.

Bottom-line

Cryogenic treatment does not improve electrical conductivity or audio performance in copper, silver, or gold connectors. While deep-freezing may enhance mechanical durability in some alloys, it does not have a measurable effect on the key parameters for audio signal transfer. Claims of audible improvements are not supported by physics, metallurgy, or controlled measurements.

6. Vibration Damping & Cable Jackets

Cables are subject to microphonic effects (vibrations affecting the signal), so damping techniques help:

● Dampening Layers: Some cables include materials like cotton or silk inside to absorb vibrations.

● Non-Resonant Outer Jackets: Soft PVC, rubber, or textile weaves help control mechanical noise.

7. Directionality and Cryogenic Treatment

● Directionality: Some high-end cables are designed for signal flow in a specific direction to optimize conductivity.

● Cryogenic Treatment: Some manufacturers deep-freeze cables to realign the molecular structure of metals, reducing resistance and improving performance.

8. Aesthetics and Branding

Beyond performance, luxury cables often have:

● Handwoven Outer Sheaths: Adds durability and an artisanal touch.

● Premium Packaging: Enhances the user experience.

● Customization Options: High-end brands offer custom terminations, lengths, and materials.

9. Testing and Auditioning

Every high-end cable undergoes:

● Rigorous Electrical Testing: To measure resistance, capacitance, and inductance.

● Listening Tests: Audiophiles and sound engineers fine-tune designs to ensure sonic purity.

The Mathematics of How Different Audio Cable Conductors Affect Signal Transmission

The performance of an audio cable is fundamentally influenced by its electrical properties, which are determined by the conductor material, geometry, and shielding.

The key parameters affecting signal transmission include resistance (R), capacitance (C), inductance (L), and skin effect.

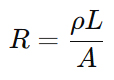

1. Resistance (R) of Conductors

Resistance determines how much energy is lost as heat when a signal passes through a conductor.

Where:

● R = resistance (ohms, Ω)

● ρ = resistivity of the material (Ω⋅m)

● L = length of the conductor (m)

● A = cross-sectional area of the conductor (m2)

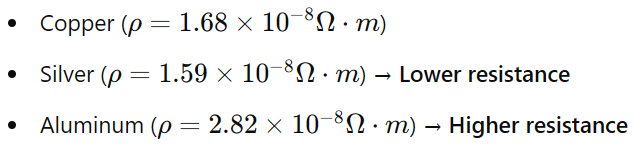

Material Comparison:

Since silver has the lowest resistivity, it offers the least resistance to signal transmission, meaning less power is lost.

2. Inductance (L) and Its Effect on High Frequencies

Inductance affects how a cable responds to alternating current (AC), especially at higher frequencies.

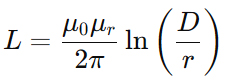

For a round conductor, the inductance is:

Where:

● L = inductance (H/m) (Henries per meter)

● μ0 = permeability of free space (4π×10−7 H/m)

● μr = relative permeability of the conductor (≈1 for copper and silver)

● D = distance to the return conductor (m)

● r = radius of the conductor (m)

Higher inductance impedes high-frequency signals, which is why low-inductance designs, such as twisted-pair configurations, are preferred for high-end audio cables.

3. Capacitance (C) and High-Frequency Attenuation

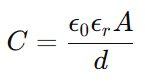

Capacitance is the ability of a cable to store charge, impacting high-frequency transmission.

For a parallel conductor system:

Where:

● C = capacitance (F/m) (Farads per meter)

● ϵ0 = permittivity of free space (8.854×10−12 F/m)

● ϵr = relative permittivity of the dielectric (varies by insulation material)

● A = area of the conductors (m²)

● d = distance between conductors (m)

Impact of Different Dielectrics:

● Teflon (ϵr ≈ 2.1) → Lower capacitance

● Polyethylene (ϵr ≈ 2.3) → Slightly higher capacitance

● PVC (ϵr ≈ 4.8) → Higher capacitance

Lower capacitance minimizes high-frequency roll-off, preserving clarity in treble frequencies.

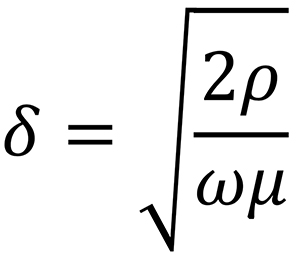

4. Skin Effect and High-Frequency Resistance

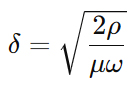

At high frequencies, current flows more on the surface of the conductor due to the skin effect. The skin depth (δ) is given by:

Where:

● δ = skin depth (m)

● ρ = resistivity (Ω⋅m)

● μ = permeability (H/m)

● ω = angular frequency (2πƒ)

For copper at 20 kHz:

δ ≈ 0.46 mm

For silver at 20 kHz:

δ ≈ 0.47 mm (slightly better conductivity)

As frequency increases, skin depth decreases, leading to increased resistance at high frequencies. This is why Litz wire, which consists of multiple insulated strands, is used in high-end cables to reduce skin effect.

Is the skin effect real?

Yes.

Skin effect is a real, well-documented electromagnetic phenomenon.

When AC (Alternating Current) flows through a conductor:

● It concentrates more toward the surface (the “skin”)

● And less through the interior

● The effect becomes stronger as frequency increases

This happens because changing magnetic fields create counter-currents (eddy currents) inside the conductor, pushing AC outward.

This is described by the skin depth formula:

Does skin effect matter at audio frequencies?

Almost never.

Here are the actual numbers.

Copper skin depth at 20 kHz (top of human hearing):

● A 1 mm diameter conductor still carries current well into the interior.

● A 2 mm diameter conductor shows only mild skin effect.

● Only when conductors exceed 3–4 mm in diameter does skin effect start to noticeably increase resistance.

Most audio cables use conductors between:

● 0.5 mm (24 AWG) and

● 2 mm (12 AWG)

These are too small for meaningful skin-effect losses at audio frequencies.

So:

Skin effect is real.

But it is negligible in typical audio cables.

Secrets Sponsor

Does conductor thickness matter?

Yes, but not because of skin effect at audio frequencies.

What thickness actually affects:

● DC resistance (lower in thicker wire)

● Voltage drop (lower in thicker wire)

● Amplifier damping factor (preserved with thicker speaker cable)

● Power handling (thicker wire dissipates heat better)

However, skin effect does not determine conductor size for audio applications.

Example:

At 20 kHz:

● 12 AWG cable:

Skin effect increases AC resistance by ~2% → negligible

● 8 AWG cable:

AC resistance increases by ~5–6% → still tiny relative to total

Skin-effect-related losses only matter at:

● radio frequencies

● switching power supplies

● transformers

● inductors

● long RF transmission lines

Not in analog audio.

What about Litz wire?

Litz wire (many individually insulated strands) is only beneficial when:

● frequencies exceed 100 kHz to MHz, or

● the conductor is very thick (multiple mm)

Audio frequencies (20 Hz–20 kHz) are far below where Litz wire offers meaningful improvement.

Using Litz for speaker wire is mostly marketing unless used in unusual geometries.

Litz wire (“Litzendraht,” German for woven wire) is a conductor made from many individually insulated strands of copper, woven in specific patterns so that each strand occupies every possible magnetic position within the bundle over the cable’s length.

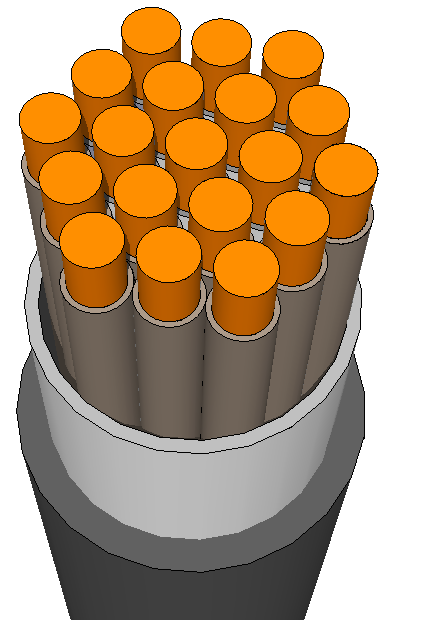

Image © https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Litz_wire

This geometry is designed to defeat skin effect and proximity effect at high frequencies.

Why Litz Geometry Works

At high frequencies (usually >100 kHz):

● Current flows mostly in the outer surface of a conductor (skin effect)

● And is pushed away from areas near adjacent conductors (proximity effect)

● Thick solid conductors, therefore, become inefficient at AC

Litz wire solves this by:

- Using many very small conductors

Each strand’s diameter is smaller than the skin depth at the operating frequency. - Making every strand follow a unique path

Over distance, each strand alternates between:

- inside and outside positions

- near and far from other strands

- exposed and shielded sections

- Ensuring the average exposure is identical

No strand stays on the outside or the inside permanently.

Therefore, each strand carries equal current over its length.

This defeats the nonuniform current distribution that plagues solid conductors.

Litz Wire Geometry Types

There are several standardized geometric arrangements:

1. Simple Bunched Litz

● Dozens to hundreds of insulated strands

● Twisted loosely together

● No formal transposition pattern

● Lowest cost, still reduces skin effect

2. Stranded / Concentric Litz

● Individually insulated strands grouped into sub-bundles

● Sub-bundles twisted together

● Layers may rotate in opposite directions

This begins true “transposition.”

3. Rope-Lay (True Litz Geometry)

This is the most common in HF applications.

Hierarchy:

● Level 0: Individual insulated strands

● Level 1: Strands twisted into a small bundle

● Level 2: Several small bundles twisted into a larger bundle

● Level 3: Large bundles twisted into a cable

Each level uses a different lay pitch and rotation direction (S/Z twist):

Level 3: Z-twist

Level 2: S-twist

Level 1: Z-twist

Strands: insulated

This ensures full magnetic exposure averaging.

4. Transposed (Weaves, Braids, and Patterns)

Advanced Litz constructions intentionally route each strand through all spatial positions:

● inside → middle → outside

● left → right → center

● shielded → exposed

● near each neighbor → far from each neighbor

Examples include:

● Basket weave

● Square braid

● Rectangular braid

● Multi-filar controlled transposition

These are used in resonant inductors, SMPS transformers, and RF coils.

Litz Wire Cross-Section Geometry

At any cross-section:

● You see many small, individually insulated conductors

● Often arranged in a hexagonal packing for efficiency

● Larger designs show bundles inside bundles (like nested circles)

Example:

o o o o

o o o o o

o o o o

If a cable is 660 strands, it might be constructed as:

10 strands × 10 bundles × 6 higher-level bundles = 600 strands

(with other combinations making the exact count)

The insulation between strands is very thin enamel, but electrically critical.

Why Litz Geometry Is Not Used in Audio Cables

Skin depth at 20 kHz in copper = ~0.46 mm.

Most audio conductors are:

● 0.2 to 1.0 mm diameter

● Far smaller than what requires Litz treatment

● Skin effect losses at audio frequencies are <2% even in very thick wire

● Proximity effect in audio is dominated by cable geometry, not strand routing

Thus:

● Litz wire is unnecessary for audio

● It offers no measurable improvement in typical audio frequencies

● It is primarily beneficial above 100 kHz or in large-gauge HF transformers

Litz Wire Summary

Litz wire is made of many individually insulated copper strands woven in precise transposition patterns, ensuring each strand spends equal time at every position within the bundle. This balances current distribution and prevents skin and proximity effect losses at high frequencies. The design can include multiple hierarchical twist levels and transposed patterns like basket weaves or rope-lay structures. While this structure provides significant benefits at RF and switching frequencies, the large skin depth at audio frequencies means that Litz geometry offers no meaningful electrical advantage for audio cables.

Skin Effect Summary

Skin effect is a real electromagnetic phenomenon, but at audio frequencies, it is too small to affect typical cable sizes. A conductor must be several millimeters in diameter for the skin effect to meaningfully increase resistance at 20 kHz. In normal interconnects and speaker cables, conductor thickness affects resistance and voltage drop, not skin-effect behavior. Skin effect only becomes important at much higher frequencies, such as RF, switching power supplies, and transformers.

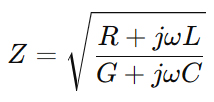

5. Impedance Matching for Signal Integrity

Impedance (Z) is a function of resistance, inductance, and capacitance:

Where:

● G = conductance of the dielectric (Siemens/m)

● j = imaginary unit

● ω = 2πƒ (angular frequency)

For optimal signal transfer, the cable’s impedance should match the input impedance of the receiving device. In audio cables, typical impedance values range from 75Ω (coaxial digital cables) to 600Ω (professional audio interconnects). Kunchur (2021) published a study on audio cables and found significant differences between generic cables and high-end audio cables (see References).

6. Practical Example: Silver vs Copper vs Litz Wire

Let’s compare a 1-meter cable of different materials at 20 kHz.

| Conductor | Resistivity (Ω·m) | Skin Depth (mm, 20 kHz) | Relative Resistance |

| Copper | 1.68 × 10-8 | 0.46 | 1.00 (Baseline) |

| Silver | 1.59 × 10−8 | 0.47 | 0.95 (Lower) |

| Litz Wire | Same as Copper but with finer strands | Negligible Skin Effect | Best at HF |

From this, silver slightly reduces resistance but is marginally beneficial over copper.

However, Litz wire significantly reduces high-frequency losses.

On the other hand, Litz wire generally has higher capacitance than a solid conductor.

Why Litz Wire Increases Capacitance

Litz wire consists of many individually insulated fine strands, each with its own dielectric layer (varnish, enamel, etc.). Because of the structure:

1. More surface area → more electric field coupling

● A solid wire has one cylindrical surface.

● Litz wire has dozens or hundreds of surfaces, each separated by extremely thin dielectric layers.

A larger surface area results in greater charge storage, leading to higher capacitance.

2. The insulation between strands acts like hundreds of tiny capacitors

● Every insulated strand touching adjacent strands forms a miniature capacitor:

● Strands touching in parallel

● Each separated by a thin dielectric (typically εr ≈ 3 – 4)

● These “inter-strand capacitors” add up to a measurable increase in total capacitance.

3. Stranding pattern increases conductor proximity

The twisting and bunching of many strands packs them tightly, much closer than two separated solid conductors.

Closer spacing → higher capacitance.

How much higher?

Typical numbers:

● Solid conductor insulation: 50–100 pF/m

● Equivalent-gauge Litz bundle: 100–300 pF/m (2–5× higher is common)

Exact values depend on:

● Number of strands

● Strand diameter

● Type and thickness of enamel

● How tightly the bundle is wound

● Presence of fillers between bundles

Does Litz wire’s higher capacitance matter for audio?

Usually no, because:

● Audio frequencies are far below RC low-pass regions for typical cable lengths

● Litz is almost never used for analog interconnect cables

● When used for speaker cables, its HF benefit (reduced skin effect) outweighs capacitance concerns

● High capacitance only becomes significant when:

● Cable runs exceed ~20–30 meters

● You are connecting to sensitive high-impedance inputs

● Using wide-bandwidth power amplifiers that dislike capacitive loads

Why Litz Wire Is Still Used

● Its advantages outweigh its increased capacitance:

● Minimized skin effect

● Each strand carries a portion of the current, keeping HF resistance extremely low.

● Reduced proximity effect

● The twisting equalizes current distribution.

● Superior flexibility

● Hundreds of thin wires bend far better than a single thick conductor.

● Better HF efficiency

● Used in RF coils, SMPS inductors, and some speaker cables.

● Capacitance is the trade-off required to obtain those benefits.

Summary

● Resistance affects overall signal strength (lower for silver, copper is nearly as good).

● Capacitance and inductance determine high-frequency roll-off (lower values are better).

● Skin effect impacts high frequencies (mitigated by Litz wire).

● Impedance matching ensures minimal signal reflection.

Silver-Coated Copper Conductors: Does It Change Signal Conduction?

Many high-end cable manufacturers advertise silver-plated or silver-coated copper (SPC) conductors. The marketing often frames this as improving “speed,” “high-frequency detail,” or “transient accuracy.” The real reasons fall into two categories: chemistry/material science and electrical behavior.

1. Electrical Effect: Very Small, and Only at RF—Not Audio

Silver is the best conductor of electricity (resistivity 1.59×10⁻⁸ Ω·m), about 5–7% better than copper. In theory, silver plating could reduce resistance if most of the current flows in the silver layer.

However, this only becomes relevant at frequencies where skin depth is smaller than the silver coating thickness.

At 20 kHz (upper audio limit):

● Skin depth of copper ≈ 0.46 mm

● Silver plating thickness in cables is typically < 0.01 mm (often 5–20 microns)

Because the skin depth is far larger than the silver layer, audio currents penetrate fully into the copper beneath. Thus:

At audio frequencies, silver plating does not meaningfully improve conductivity.

It matters only in RF/microwave applications (MHz–GHz), where current flows almost entirely in the outer layer.

2. The Real Reason: Copper Reacts Chemically With PTFE (Teflon)

This is the actual engineering reason silver plating is common in PTFE-insulated wire.

Copper + PTFE + heat + moisture → copper fluoride and carbonaceous decomposition

This reaction:

● darkens the copper

● increases surface corrosion

● eventually increases surface resistance

● weakens the insulation over long periods

PTFE is an outstanding dielectric (εr ≈ 2.1), but it is chemically aggressive toward bare copper at the wire interface.

Why Silver Solves This

Silver is:

● chemically inert against PTFE

● highly corrosion-resistant

● a barrier layer between copper and the dielectric

● easy to electroplate thinly and uniformly

Thus, the silver layer prevents the copper/PTFE reaction long-term.

3. Does Silver Plating Improve Sound?

Electrically measurable benefits at audio frequencies: none or negligible.

Chemical/material benefit: major for longevity.

Manufacturers may advertise it as an electrical upgrade, but engineers use it primarily because PTFE requires a noble metal interface.

This is why:

● aerospace wiring

● military specification wire (e.g., MIL-W-16878/4)

● RF coax

● high-reliability medical cabling

all specify silver-plated copper + PTFE.

The process for CNC machines to extrude each conductor and wind them into the required shape, then surround the cable with a protective covering, is very complex and expensive.

CNC machines in cable manufacturing operate with a high degree of automation and precision to produce conductors, wind them into the desired geometry, and then apply protective coverings. Here’s a simplified overview of the typical process:

1. Conductor Extrusion (Metallic Core Formation)

This step isn’t exactly “CNC” in the traditional sense, but is often integrated into CNC-controlled systems.

● Input Material: Copper or aluminum rods.

● Process: The rods are fed into a wire drawing machine, which reduces the diameter through a series of dies.

● Annealing: The drawn wire is heat-treated (annealed) to improve flexibility.

● CNC Control: CNC systems control the tension, speed, and diameter to ensure precision.

2. Stranding / Winding into Geometry

This is where the CNC aspect really takes over.

● Stranding: Multiple wires are twisted together to form a conductor. This can be:

- Bunched

- Rope lay

- Segmental conductors for special applications

● CNC Control: Controls rotation speed, pitch length, and feeding systems to match the desired geometry and minimize electrical resistance/skin effect.

3. Insulation Extrusion

Once the conductor is formed, insulation is applied via extrusion.

● Materials: PVC, XLPE, Teflon, or other polymers.

● Process: The conductor passes through an extrusion head where molten insulation is applied.

● Cooling: The insulated wire is cooled (usually in water baths) and solidified.

● CNC Control: Monitors the extrusion rate, diameter control, and alignment.

4. Assembly / Cabling

If the cable contains multiple conductors:

● Twisting and Assembly: Multiple insulated conductors are twisted together into bundles.

● Filler Materials: May be added to keep a circular cross-section.

● CNC Control: Handles twist rate, spacing, and synchronization across all axes.

5. Shielding and Jacket Application

This gives the cable its final shape and protection.

● Shielding (Optional): Braiding or wrapping of metal foil or wire for EMI protection.

● Outer Jacket Extrusion: Final protective layer (rubber, PVC, etc.) extruded onto the cable.

● Marking: Cables may be laser-marked with serials or specs.

● CNC Control: Ensures uniform jacket thickness, proper alignment, and final quality control.

6. Testing & Quality Control

● High-voltage testing

● Dimensional checks

● Capacitance and resistance testing

● CNC Logging: Modern lines often log all process parameters for traceability.

The Types of Machines Required for Manufacturing Cables

1. Type of Cable Being Manufactured

● Standard cables (e.g., building wire, power cables, ethernet, etc.):

- Use off-the-shelf machines from established manufacturers.

- Modular systems are common; you can combine standard extruders, winders, and jacketers.

● Specialty cables (e.g., aerospace, medical, high-flex robotics cables):

- Often require custom machines or heavy customization of existing ones.

- Things like non-round geometries, hybrid cores, or superfine wires need precision setups.

2. Volume and Production Scale

● High-volume production lines (like those for telecom or automotive suppliers):

- Will often customize or fully design machines to optimize speed, yield, and efficiency.

- CNC control systems are tailored to tightly integrate with QA, ERP, and robotics.

● Low-volume or prototyping setups:

- Might use more versatile general-purpose equipment with swappable dies, tooling, and programming.

3. CNC Integration

● Modern wire/cable machinery comes CNC-enabled, but how much CNC control is needed determines if off-the-shelf is enough.

- For basic extrusion: standard machines with basic CNC interfaces are often sufficient.

- For complex winding geometries (like coaxial, twisted pairs, litz wire, braided shielding, etc.), you might need:

● Custom spooling and tension control systems

● Precision winding heads

● Multi-axis servo control, which may require specialized CNC systems.

4. Tooling and Dies

Even standard machines often require custom tooling and dies for:

● Specific conductor sizes

● Custom-shaped insulation

● Multi-layer extrusion

● Unusual winding patterns

An Example

Say you’re making a high-performance cable for electric vehicles:

● You might use a standard rod breakdown machine to prep your copper.

● But the stranding machine might be a custom-made unit to control exact lay length and cross-section for better conductivity.

● Then your jacket extrusion might be standard again, but with a custom cooling and laser marking station.

And, for High-End Audio Cables?

These cables might look simple, but they’re a whole different game in terms of performance expectations and design. Let’s dig into whether you’d need custom-made machines or can get away with standard gear.

What Makes Hi-Fi Audio Cables Special?

Hi-fi audio cables are all about:

● Signal purity (low resistance and capacitance)

● Shielding from interference (EMI/RFI)

● Precision geometry (twist rate, conductor spacing, etc.)

● Exotic materials (silver, oxygen-free copper, etc.)

● Vibration damping and aesthetics

That means even if the basic principles of manufacturing are the same, the tolerances and attention to detail are much higher.

Do You Need Custom-Made Machines?

You Can Use Standard Machines… If:

● You’re making simple twisted-pair or coaxial cables using:

- High-purity copper or silver conductors

- Standard insulators like PTFE, polyethylene, etc.

● You’re okay with manual tweaking and slower production speeds

● You’re producing in small batches or for boutique retail

You can use:

● Standard wire drawing + annealing machines (for conductor prep)

● Precision stranding machines (with controllable twist lay)

● Small-scale extruders with changeable dies

● Manual or semi-auto braiding and shielding stations

You’ll Need Custom or Specialized Equipment If:

● You want ultra-consistent geometry (for L/R channel matching, or impedance control)

● You’re working with non-traditional shapes (flat cables, ribbon layouts, etc.)

● You require multiple conductor materials or gauges in one bundle

● You need advanced shielding like braid over foil over twisted pairs

● You’re integrating aesthetic outer jackets (fabric braiding, transparent sheaths, etc.)

In that case, you’d customize:

● CNC-controlled winders with precision lay length control

● Multi-stage extruders for layered insulation/jacketing

● Tension-control systems for ultra-thin wires (e.g., silver-plated strands)

● Braiding machines that work with fine or aesthetic materials (silk, PET, nylon)

Summary:

| Component | Standard Machine | Custom Needed? |

| Wire Drawing / Annealing | Yes | Not usually |

| Stranding/Twisting | Yes | For special geometry |

| Insulation Extraction | Yes | For multi-layer or exotic materials |

| Shielding / Braiding | Yes | For fabric, multi-layer, or tight pitch |

| Outer Jacket / Finish | Yes | For unique aesthetics or shapes |

Some premium cable brands claim features like “directional signal flow,” cryogenic treatment, or “hand-crafted twist geometry.” Whether these claims are marketing or not, maintaining those physical arrangements often requires custom-built machinery or at least manual final assembly. Such equipment is very costly, which partly explains why complex high-end audio cables are priced so high.

It is impossible to minimize resistance, capacitance, and inductance all at once because changing the geometry to lower one often increases at least one of the others. This trade-off is fundamental to electromagnetics and affects all types of audio or RF cables.

1. Resistance (R)

Resistance depends only on:

● conductor material resistivity

● cross-sectional area

● length

To reduce R:

● increase conductor diameter, or

● use a lower-resistivity metal (copper → silver → gold in order of conductivity)

Resistance is independent of C and L, so you can lower R without affecting them much.

2. Capacitance (C) and Inductance (L) Trade-Off

This is where the unavoidable trade-off happens.

Both C and L are determined by the geometry of the conductors and the dielectric properties around them.

Capacitance increases when:

● conductors are closer together

● conductors have a larger surface area

● dielectric constant (εr) is higher

● shield is close to the inner conductor (coax)

Inductance increases when:

● conductors are farther apart

● loop area is large

● return path is distant

● conductor spacing increases

Therefore:

● Lower capacitance → conductors farther apart → higher inductance

● Lower inductance → conductors closer together → higher capacitance

This is not a design flaw; it is a physical law.

You can think of it as a seesaw: any attempt to push one down pushes the other up.

3. Examples

Coaxial Cable

● Center conductor very close to shield

● Low inductance

● High capacitance

Used where controlled impedance is needed (digital, RF), but too much capacitance can roll off high audio frequencies in long runs.

Widely Spaced Speaker Cables

(e.g., flat ribbon designs)

● Conductors spaced far apart

● Low capacitance

● Higher inductance

High inductance can soften treble or interact with amplifier output filters.

Twisted Pair

● Conductors are very close

● Small loop area

● Low inductance

● Moderate-to-high capacitance depending on twist pitch and dielectric

This is why twisted pair is quiet (low EMI) but not always ideal for long analog audio runs where capacitance matters.

4. Is there a “best compromise” design?

Yes. High-end audio cable designers often aim for:

● Moderate spacing (not too wide or too tight)

● Low-εr dielectrics (PTFE, foamed PE, air tubes)

● Carefully controlled twist (reduces L without driving C too high)

● Multiple conductors arranged to shape electromagnetic fields

Using a low-εr dielectric is the one “free” improvement:

● Lower εr lowers capacitance

● Without requiring larger spacing that would raise inductance

But even here, the trade-off still exists, just less severely.

5. Summary

A cable cannot be optimized at the same time for the lowest resistance, capacitance, and inductance. Resistance can be reduced independently by using larger or more conductive metals, but capacitance and inductance are linked through their geometry: decreasing capacitance requires increasing conductor spacing, which in turn raises inductance, while reducing inductance involves bringing conductors closer together, which increases capacitance. High-end cable design mainly involves balancing these conflicting electromagnetic factors.

Secrets Sponsor

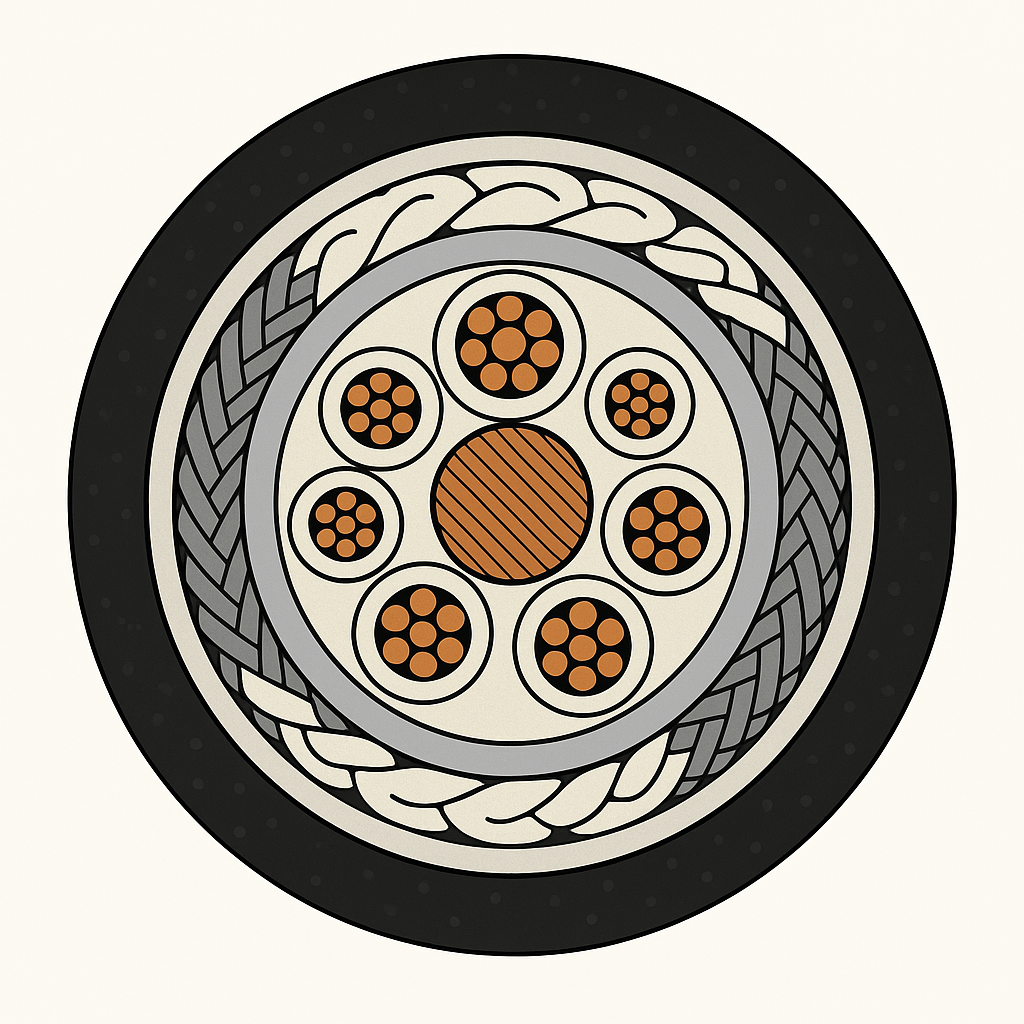

Here’s a conceptual example of a high-end audio cable cross-section designed for audiophile-grade speaker cables or interconnects. It features multiple conductor diameters, specialized shielding, and a layered structure optimized for signal clarity, frequency separation, and minimal interference.

Structure Overview (from center outward):

1. Central Core Conductor:

- Material: Solid silver-plated copper

- Diameter: ~1.5 mm² (for low-frequency current carrying)

- Purpose: Handles the bulk of the low-end (bass) signal, lower resistance path.

2. Surrounding Spiral Conductors (x6):

- Material: High-purity OFC (oxygen-free copper)

- Diameter: ~0.25 mm² each

- Layout: Evenly spaced in a spiral wrap around the central core.

- Purpose: High-frequency detail (treble), better skin effect management.

3. Dielectric Separation Layer:

- Material: Foamed polyethylene (FPE) or PTFE

- Thickness: 0.5 mm

- Purpose: Low dielectric constant, maintaining conductor spacing, and reducing capacitance.

4. Inner Shield (Optional):

- Material: Aluminum foil wrap (100% coverage)

- Purpose: EMI protection without compromising flexibility.

5. Braided Shield:

- Material: Tinned copper braid (90% coverage)

- Purpose: Extra shielding and mechanical protection. It also serves as a ground plane.

6. Damping / Filler Material:

- Material: Cotton or synthetic fiber strands

- Purpose: Reduce microphonics (mechanical vibrations), maintain shape.

7. Outer Jacket:

- Material: Flexible PVC or TPE with optional nylon braid overlay

- Color/Finish: Matte black or clear to show off internal geometry

- Diameter: ~8–12 mm overall, depending on spacing

Why Use Multiple Diameters?

● Skin effect: High frequencies naturally flow toward the surface of conductors. Smaller-diameter wires carry high frequencies more efficiently.

● Frequency separation: By physically isolating conductor sizes, you reduce interference and allow more “natural” signal paths.

● Signal phase coherence: Careful layout of conductors with staggered sizes helps preserve timing and dynamics.

High-end cables optimize these parameters through material selection, conductor geometry, and dielectric properties to ensure maximum signal fidelity, particularly in audiophile and professional applications.

The craft of designing high-end audio cables combines science with craftsmanship. While there is legitimate debate about the audibility of differences, careful engineering, top-quality materials, and precise construction methods all help achieve a superior quality final product. These cables often feature high-purity conductors like oxygen-free copper or silver, advanced shielding to reduce electromagnetic interference, and specialized dielectric materials to maintain signal integrity. The manufacturing process is labor-intensive, often involving hand assembly and strict quality checks, which increases costs. Consequently, the price of these cables reflects not only the quality of the materials but also the expertise and time invested.

For music lovers and professionals who seek the best performance, high-quality cables are a necessity, and by their nature do not need to be stratospherically expensive. For well-heeled audiophiles who want the last word in quality, appearance, and personal satisfaction, there are a plethora of finely crafted cable choices out there to suit every taste.

REFERENCES

Ballou, Glen – Handbook for Sound Engineers (6th Edition, 2015)

Whitaker, Jerry C. – The Electronics Handbook (2nd Edition, 2005)

Ott, Henry W. – Electromagnetic Compatibility Engineering (2009)

Jung, Walter G. – Audio IC Op-Amp Applications (1994)

Self, Douglas – Small Signal Audio Design (4th Edition, 2020)

Van den Hul, A. J. – The Importance of Cable Geometry in Audio Transmission (White Paper)

Hawksford, Malcolm Omar – The Essex Echo: An Investigation into the Audibility of Cable Phenomena (AES Paper, 1985)

Olson, Harry F. – Elements of Acoustical Engineering (1947, Reprint 1991)

Belden Cables – Balanced vs. Unbalanced Audio: Cable Design Considerations

Mogami Cable – Why Star Quad Cables Reduce Noise Better

Canare Corporation – Microphone Cable Construction and Noise Reduction

Cardas Audio – Golden Ratio Stranding and Audio Cable Physics

Journal of the Audio Engineering Society (JAES)

IEEE Transactions on Electromagnetic Compatibility

Proceedings of the AES International Conference on Audio Design

Megatest speaker cables – real measurements, samples and blind test!, 2022

High-end vs. Generic Cable Measurements

Kunchur, Milind – An electrical study of single-ended analog interconnect cables, IOSR Journal of Electronics and Communication Engineering (IOSR-JECE) e-ISSN: 2278-2834,p-SSN: 2278-8735.Volume 16, Issue 6, Ser. I (Nov. – Dec. 2021), PP 40-53 https://www.iosrjournals.org/ – https://www.iosrjournals.org/iosr-jece/papers/Vol.%2016%20Issue%206/Ser-1/E1606014053.pdf