Well, my passion for headphones was, in large measure, because they brought me the magical world of binaural recordings. In some of the reviews I’ve written, I’ve included recommendations of binaural recordings made by musicians who are now recording for headphones, as well as some of the extraordinary recordings of pristine natural locations by Gordon Hempton. Of course all these recordings sound terrific played on speakers, but the gateway to the magic is only through headphones.

The first time I heard a binaural recording was in 1991, while taking some computer/multimedia courses at a local state university. A classmate had just come back from a trip to Ireland and he was showing this strange, 2 microphone headset he wore when recording a sound journal of his trip. He talked about how he could make three-dimensional, 360-degree, immersive soundscapes that would bring his experiences to life when he shared his stories. He talked about the fabled pubs of Dublin and his recording of walking into one. I asked if he was going to play them for the class, and he explained that you could only hear the effect through headphones. I remember the moment when he handed the headphones over to me and I put them on. To this day I can still feel the effect it had on me as I closed my eyes and was plunged into a three-dimensional world of conversation, laughter and music…suddenly, over in the corner, about 20 feet away…a fiddle and guitar. Loud, raucous singing and shouting Irish voices all around me. It was startling! And I was hooked.

Recording in binaural is a variation of recording in stereo. Instead of single mics, a pair of horizontally positioned mics placed a head’s width apart recreates how we use our ears to place sounds three-dimensionally in space and distance. Two microphones are placed in ear-like cavities on either side of a dummy head or placed on the recordist’s ears. Because the dummy head shape recreates the density and shape of a human head (this is referred to as Head-Related Transfer Function, or HRTF, or Anatomical Transfer Function, or ATF), the microphones will capture all the acoustic data the brain uses to echolocate and create an aural image of the environment, thus delivering sound as it would be heard by the human ear in all its three-dimensional glory.

Though I enjoy binaural music recordings, my heart lies with field recordings. I often walk through the urban world with my listening turned down; if I stayed open and gave the attention I give when I listen to music, I would probably be driven a bit mad by the cacophony. On the other hand, when I am hiking through woods and the hills of the nearby parks, I listen closely. Each step takes me further into the embracing sounds of the natural world, and I breathe deeply, my thoughts slow down and I am re-balanced and restored. I have the same physiological response when I listen to binaural field recordings. Sitting down in a comfortable place, closing my eyes and listening to recordings of the natural world for 20 minutes is all it takes to restore myself to more balance and a sense of peace.

Several years ago, I was on a quest to find high quality nature recordings. I was disappointed in the recordings I found. Either they had new-age music blended in or short repetitive loops recorded in low fidelity. All I wanted were some well-recorded natural evening sounds with crickets. How hard could it be? I was at a nature store in Berkeley, asking about nature recordings and they steered me to the binaural recordings of an Emmy award-winning nature recordist named Gordon Hempton. I was directed to his website called One Square Inch of Silence, where I learned about an organization he founded, devoted to recording the planet’s remaining quiet places that are free of human intrusion. Not only did I find a wealth of exquisite binaural recordings that turned me into an armchair adventurer, (his recordings can be found on all the music streaming sites) but I found an inspiring human being who had made it his life’s work to capture the vanishing pristine places. His recordings are used by National Geographic, the Smithsonian, and film makers, just to name a few. His studio and location for some of his recordings was on the Olympic Peninsula in Washington State.

Secrets Sponsor

I have a brief story about Gordon Hempton that I would like to share, since it lays the foundation upon which my mild obsession with these recordings is built. About ten years ago, my husband and I spent a week in the San Juan Islands. It happened to be my birthday, and my husband gave me a card, with a note from Gordon Hempton inviting me to spend the afternoon with him at his studio. My husband, knowing I was a fan, had called Gordon up a few months before and told him about my passion for his recordings. He asked if there were any workshops he could sign me up for, as we were going to be driving through the Olympic Peninsula. Gordon said there weren’t any at the time, but he would be delighted for us to be his guests for the afternoon, and that he would introduce me to the basics of binaural nature recording.

The Olympic Peninsula is a breathtaking place. Mountains rise from sea level to almost 8,000 ft. There are immense moss-draped rain forests and rocky, driftwood strewn beaches; all within sight of Seattle, across the Puget Sound. We found Gordon’s studio and home up a long gravel road. There was a colorful yurt, an old cabin, a small separate studio, and a propane-fired clawfoot bathtub next to a firepit. We were greeted warmly by Gordon who gave us a tour. He introduced me to Fritz, his KU-81-u Neumann Binaural head, and pointed out his standard gear; a long pole to which Fritz was attached, a Sound Devices 722 digital audio recorder and a set of Sennheiser HD 25-1 headphones. Since I was a novice, and really didn’t have the expectation of being taught how to make recordings in those few hours, what I did learn was how to listen to the sonic personality of the woods; not with my head, but with my gut. The technology is simple, and he showed me the headphone splitter I would wear that allowed me to monitor the sounds the microphones on Fritz’s head were recording, and the headphones allowed me to listen to my surroundings through Fritz’s “ears”. We walked along a nearby stream and Gordon had me moving Fritz around; inches above the rushing water, then up along the bank, then behind boulders. He told me to listen to the reflected sounds and how they contributed to the sonic images I was recording.

At first, I was self-conscious; terrified of dropping Fritz into the rushing water. Gordon told me to breath and slow down; feel more, think less. At first, hearing through mics located a few feet away left me feeling a little woozy and disoriented, but we would stop, I would take off the headphones and he would point out the various species of trees around us. He had trained as a forester and not only did he open my ears, but my eyes as well, as I soaked up the green beauty of the Bigleaf Maples. We moved soundlessly through the forest; gliding and pausing as he would cup his ear and point; a signal to listen to something he was hearing. The more I surrendered to the rhythm of stopping, moving Fritz around, and sometimes closing my eyes to “see” with my ears, the more layers of sound I became aware of. By the end of our time along the stream and in the woods, I could barely speak, I was so attuned to the exquisite field of sound around us. We returned to his studio where he demonstrated how he downloads the recordings into his computer. We studied the wave forms displayed on his monitor as we listened to what I had recorded. Honestly, what I heard being played back wasn’t very impressive; like the photos someone might take when handed a camera for the first time. It deepened my appreciation of the artistry Gordon brings to his craft and the worlds he captures so brilliantly for us to enjoy.

For me, this antidote describes just how much binaural recordings can reach deeply into the emotional side of our listening. In fact, I have a theory that the human species survived, not just by the visual, but more importantly by echolocation which expanded our awareness beyond the field of vision. The snap of a twig 20 feet behind; the slither of a snake five feet away in the dark of night. I think our DNA is encoded to respond deeply to our auditory world. I dare anyone to put on headphones and listen to a good binaural recording, whether of music or soundscapes and not be captivated by what they hear.

I have a few recommendations that I think represent some of the most well-produced recordings I’ve heard so far in my binaural adventure. Any headphones will do, and if your listening environment is noisy, closed-back headphones might be best, but I find that open-back headphones give a more natural and open sound that let the recordings breath and expand, especially with nature recordings.

Secrets Sponsor

Leading off, are the recordings of Gordon Hempton. All the major music services carry most of his recordings. “Desert Thunder (Kalahari, South Africa, October 30, 1990”, is an extraordinary introduction to both the caliber of his recordings, but also to his cinematic vision of bringing soundscapes for us to enjoy from places in the world we would probably never visit on our own.

One of the field recordings that captures the magic of armchair traveling comes from “The Sound Traveler, SpaceX Falcon Heavy Launch, Vehicle Assembly Building Pad 30A”. The Sound Traveler is a binaural audio YouTube channel that currently has 24 binaurally recorded videos designed to take the viewer to various locals for a “you are there” experience. Like the spectacular recordings of Gordon Hempton, these recordings highlight the transportive magic of binaural. Through these recordings you can walk through the streets of Paris, experience Victoria Falls, browse in an outdoor market in Colombia, South America, walk through a Shinto shrine in Japan and twenty other adventures. My favorite and must see/hear is the SpaceX Falcon Heavy Launch recorded from the rooftop of the Cape Canaveral Vehicle Assembly Building. One of my grand wishes is to experience a rocket launch close enough to feel and hear it in all its glory. Until then, this recording gets me close. The video is recorded by a rocket photographer traveling with a select group of fellow rocket enthusiasts. The journey takes you to the roof of the building where this privileged group sets up for the best seat in the house for a Falcon Launch and the return of the two first stage rockets. All I can say is if there is one recording that can deliver what binaural recording can be, it is this video. Crank it up!!

I find binaural music recordings often more subtle compared to field recordings, especially with symphonies, since when listening live, the sound is all enveloping, reflected from surfaces in all directions, so pinpoint location cues aren’t necessary. However, they can convey a sense of liveliness and presence beyond a standard recording, without becoming “gimmicky”.

I found a recording company named Chasing The Dragon Audiophile Recordings based out of an old church in London to be an extraordinary find because they record with a huge array of mics including valve microphones, and a Neuman KU-100 binaural head. This small award-winning record company thinks it is worthwhile to record for those of us who love our headphones, along with their direct-to-disk LPs and other traditional recordings. Their binaural recordings, in 24-bit 192 kHz are available on disc and WAV file downloads. “España” is one of the albums available for headphones, and the recording of the National Symphony playing Rimsky Korsakov’s Capriccio Espagñol is stunning. The dynamics are powerful, and though it is not obvious it is a binaural recording. At the end of the piece the recording includes the sound of the musicians turning the pages of the scores and shifting in the wooden chairs; the 3-D effect lets you know this is binaural.

Another symphony recording is the Pasadena Symphony, conducted by Jorge Mester. Stravinksy’s “Le Sacre Du Printemps” and Rachmaninoff’s “Symphonic dances” recorded in 20-bit high-resolution on a Neuman Ku-100 microphone system, monitored with Sennheiser HD 580 headsets and recorded and mastered direct-to-disk on a 24-carat gold pressing. Pretty swanky! The recording is powerful, the dynamics are punchy, yet again, the effect of binaural is a subtle enhancement, as it should be in this setting.

Ottmar Liebert’s “Up Close” CD 16-bit 44.1 kHz-Stereo album on the other hand, fully exploits the power of binaural to great effect. His flamenco and Spanish style guitar playing shimmers on this recording. When there is hand clapping or calling out, I found myself turning around looking for the sound before realizing it was on the recording.

Jeanne Michel Jarre’s “Amazonia,” Hi-Res 24-bit 48kHz-Stero is a mind-bending soundscape montage of Amazon rainforest field recordings, native voices and electronic music. Recorded to accompany a gallery show of the photographs of Sebastiao Salgado, the album cover says, “for headphones only”, and I can’t imagine listening to it any other way.

One of the most well-known masters of recording in what he calls Binaural + is multi–Grammy Award winning Dr. David Chesky, whose album “Dr. Chesky’s Sensational Fantastic And Simply Amazing Binaural Sound Show!”, Apple Lossless, a collection of various musicians, that range from the folk/jazz of Amber Rubarth to the Arabian orchestral music of Sami Bayyati. I found some of the recordings to be stellar examples of the beauty of binaural, and a few others to be less so, but all in all a playful and wide-ranging recording.

Pearl Jam, “Binaural” Hi-Res 24-bit 192kHz is the only binaural recording they did, as far as I know. It was met with some confusion at first, but for some became a cult favorite. I found the song “Of the Girl” to be sonically complex and more interesting than the rest of the album, which is too grunge for my taste, but they get points for experimenting.

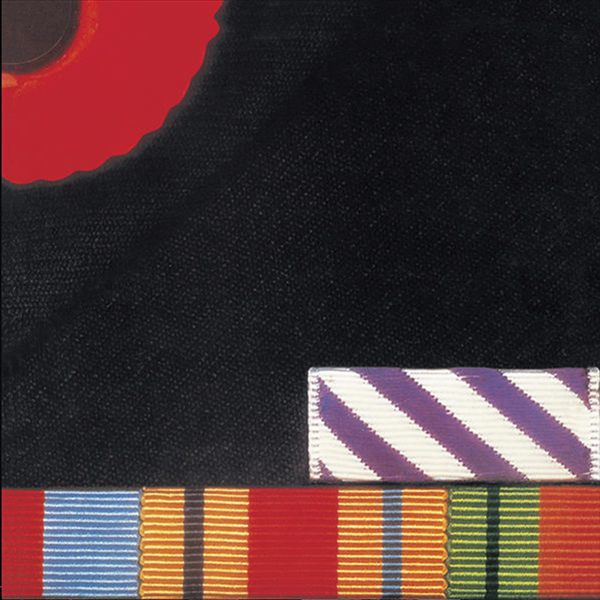

Pink Floyd, “The Final Cut”, 24-bit 192 kHz was released four years after “The Wall”. Written by Roger Waters, it is an anti-war opera, which uses layers of binaural soundscapes at the beginning of each song. This album was not as popular as many of the other albums, but it is brilliant in its cinematic/auditory telling of the ravages of war balanced against the delicacy of a child’s experience of life as well as a protest against old men running the wars and young men fighting and dying for them. A powerful masterpiece, in my opinion.