Feature Article -

An Interview with "Dead Man Walking" Opera Composer Jake Heggie and Baritone

John Packard - April, 2002

Jason Serinus

![]()

Introduction

Most new operas receive an initial production, and then

languish or disappear. Not "Dead Man Walking", the emotionally riveting first

opera by composer Jake Heggie and librettist Terrence McNally.

Fashioned after the 1993 best-selling book by Sister Helen Prejean, the opera

received its much-heralded San Francisco Opera premier in October 2000. Since

then, Dead Man Walking has become the subject of PBS documentary that airs

throughout the US in 2002; received a mesmerizing live recording (Erato 86238-2)

featuring its superb premier cast captured in fine ambient sound; and been

scheduled in a completely new production by eleven international opera companies

in Orange County, Cincinnati, New York City, Boston, Detroit, Pittsburgh,

Baltimore, Southern Australia, Houston, and an as yet unrevealed major American

city.

The Interview

On April 1 and 4, I conducted separate phone interviews with composer Jake Heggie and lead baritone John Packard. Here is the complete transcript, beginning with Jake Heggie:

JS: I was deeply moved by one of the SFO premier performances of Dead Man

Walking. Unfortunately, I attended the night that mezzo-soprano Susan Graham,

who played Sister Helen Prejean, was absent due to the death of her father. So

it was wonderful to finally hear her on the new recording.

Jake Heggie: Oh yes. She's so strong.

You wrote the role of Sister Helen specifically with Susan Graham's voice in

mind?

Yes. Initially, when Terrence and I came up with the idea, we had to come up

with someone's voice to model the role after. Once I decided that the role was

for a lyric mezzo, and I didn't know I could get Susan, I had a couple of

people's voices in mind: my friend Frederica Von Stade and Janet Baker. That's

the model we settled on as we got going, dramatically, vocally, and

personality-wise.

When the search began to see who would not only be free and available but also

enthusiastic about doing it, Susan quickly got right on board.

When you were thinking of Janet Baker for the lead role, was she still capable

of singing it?

Oh no, we were thinking of her and of Frederica Von Stade in their youthful

prime – those kinds of voices. Terrence told me that he wrote a lot of roles in

his plays with Lawrence Olivier in mind, but Olivier never acted in a single one

of them.

I downloaded your bio from your website, www.jakeheggie.com. It's a very long

bio . . .

Don't ever do that . . . .

When did you and Terrence first come up with the idea of transforming Dead Man

Walking into an opera?

Initially our mandate from SFO General Director Lofti Mansouri was to do a

comedy. [Laughter] It was the new Millennium, and he wanted something

light-hearted and celebratory. Terrence could not have been less interested in

that idea. He really wanted his first opera to be a tragedy and a drama,

something contemporary but sort of timeless, something very American that has a

universal feel to it – a story that's gone on over and over.

We were both trying to figure out ideas when he was walking down the street in

New York one day and suddenly Dead Man Walking popped into his head.

Had he read the book or seen the movie?

He'd seen the movie. I had avoided seeing the movie up to that point because

I didn't want to go into the emotional turmoil that I knew the movie was putting

people through. It really scared me. So when he suggested the subject, I knew

about the movie, but I hadn't seen it.

When Terrence suggested Dead Man Walking as an opera, even as he was going

through a list of other possibilities, my mind remained so focused on the idea

because it made so much sense. It's an intimate drama, but it's got that huge,

sweeping drama that can fill an opera house. It makes sense for the people who

sing; it's also American, and pretty timeless.

Timeless and timely.

Right. I immediately started hearing the kind of music and textures I would

want to write to tell its kind of story of transformation.

When did this decision happen?

Terrence suggested the idea in early June 1997. He had other projects to do,

and we had to make sure we had rights, so we didn't start announcing the project

and writing until March of 1998.

We took off to his house in Key West to work together. Terrence wrote the first

act libretto in about four days (chuckling). Then it was up to me. I told him it

was going to take a little longer than four days.

I came out to California. I had the first act done by August, and finished the

second act the following summer.

So you didn't pull a Mozart/Handel compositional quickie?

No. [Laughing] Those boys did very well by that. I'm not that clever.

Had you and Terrence worked together before?

No. That was our first time. Lofti Mansouri put us together. When Lofti came

to me and suggested he was considering me to write a new opera, he said I might

get along very well with Terrence McNally. It seems he'd been very interested in

getting Terrence involved in writing an opera for a long time.

Terrence had been approached by many, many people about writing an opera, but he

didn't say yes until this one. So it was really a case of Lofti going out on a

limb and putting all of this together. He made sure everything was put together

with care, the way we wanted it, and first rate.

He's come into a lot of criticism for his tenure at San Francisco Opera. It's

good to hear the other side as well.

I sat in the first row for Susan Graham's Berkeley recital, and I struck by how

open her heart is. I saw this incredible openness, which I also feel when

listening to the recording.

Incredible openness and vulnerability, accessibility, warmth, very connected

to what she's singing – not just the words, but the whole psychology behind the

words. Very much in touch with that. Very much a vessel that's sharing and

giving back. It's very generous. The sound is generous, the whole personality is

generous.

She's remarkable, because not only does she have that vulnerability, but she

also has incredible strength. It's the combination of those things that makes

her a special artist. Like Von Stade, who has those same qualities.

I sat in the first row when Von Stade appeared in a benefit performance in San

Francisco. I was reviewing it for Opera News. It was tremendous to hear her so

close. And you were the pianist.

I was so lucky to be playing that night.

It's impressive to read how many opera companies are slated to produce Dead Man

Walking.

Opera Cincinatti, New York City Opera, Boston, Detroit, Pittsburgh,

Baltimore, Adelaide in Australia. A small company in Germany has it on the

books, and Houston, which had to postpone its initial performances, is about to

reschedule. There's also another company in this country that's very exciting

that I can't tell you about yet.

Has any other American opera had such rapid success?

Perhaps Gershwin's Porgy and Bess or Carlisle Floyd's Susannah.

But did they both get so many performances so soon after their debuts?

I don't know. Susannah was pretty popular from the beginning. Porgy was done

as both an opera and a Broadway show, but it has endured as an opera. And it

depends what you feel about Sweeney Todd and those kinds of pieces. [Menotti's

Amahl and the Night Visitors was originally written for TV, and has had numerous

performances since].

I know that Mark Adamo's Little Women, whose Houston premiere has been aired

on PBS, is getting performed a lot. [See the extensive interview with Mark Adamo

in the Secrets archives].

I think opera audiences are eager to hear new work. But it has to be work that

doesn't throw them completely off guard. Most American opera audiences have been

pampered with classics. It's a tough move to go right into new repertoire, or to

suddenly jump into what Europe has been doing for years. So these are the kinds

of pieces that might make the transition easier.

What kinds of pieces has Europe been doing for years?

I'm talking about pieces by Berio, Ligeti, Henze – pieces that your average

American opera audience would probably have a lot of trouble with. They haven't

had to deal with that force of musical innovation.

And they're surely not going to hear it on most FM classical stations.

Right. We have a different music tradition over here as well. We're very

influenced by movies and television, and by Broadway. Because American opera is

private funded, not state funded, it doesn't always have the luxury of jumping

toward innovation. Opera directors and boards really have to think about the

audience and their public. That's held our audiences back a little bit in terms

of their openness to new work.

Hopefully works that myself and others are doing will open a gateway so people

will be a little less scared of hearing some of those great works by Henze,

Ligeti, Berio and all of those guys.

How would you describe your music to someone who might wish to explore the

opera?

It's very lyrical. I'm certainly a tonalist, but I like to step outside every

now and then. I'm very conversational with lots of parts of it, so the parts

where melody takes over and sweeps you up mean even more. That's all very

planned out by me.

Influences on me have included everyone from Benjamin Britten, Copland, and

Barber, to Poulenc, Debussy, Bernstein and Gershwin. And John Adams and Chris

Isaak.

Gramophone's review says that your opera is “a cross between the style of

Broadway operas of the 1940's with more than a nod in the direction of late

Italian verismo, laced with traditional American hymns . . . .”

I haven't seen the review yet. Is it bad? If it's bad, I don't need to read it

anyways. I don't necessarily pay attention to reviews.

The reviewer writes, “Although the language is that of soap operas, it is very

well constructed.” How does it make you feel to hear that kind of criticism?

That's that person's opinion. There's not much I can do about it, so I don't let

it bother me too much.

Reviews and criticism are all opinion pieces. Everyone has a different opinion.

It's kind of amusing. I've been on the best of list and the worst of list for

the same piece. As an artist, you have to stick to what you know and what you

believe.

Speaking of which, what is your own orientation around the death penalty? What's

Terrence's? How did your feelings interface with composing this opera?

Before we decided to do it, I felt ambivalent about the death penalty. Like a

lot of people, I hadn't really reflected on it much in very serious terms; I

hadn't gone to that place and thought about the real people involved. Instead I

thought, “Well, they're probably getting what they deserve. It sounds reasonable

to me.”

But once you get into the story, and think about all the people involved and the

cycle of violence that's perpetuated – and you also think about if it was your

own child or relative who had done the killing, as opposed to thinking that if

someone did that to my child or relative, I'd want them dead -- you might think

a little differently.

We very often create monsters in order to conveniently put these people out of

the human race. But working on the opera took me to a different place. I'm

completely opposed to the death penalty now. I don't think we have the right to

play God like that. I believe in life in prison without parole.

We're also human beings. We make mistakes all the time. Our legal system is not

perfect. If it were perfect, it would be another thing. But it never will be,

because it's run by humans.

The death penalty is pretty drastic. Killing something is the one thing you

cannot take back. So I'm totally opposed to it. Besides, I really do believe

that it just perpetuates violence.

In that regard, the story is like a microcosm of what's happening in the Middle

East right now. On Easter night, I channel surfed between tanks rolling into

Palestinian territories and Charlton Heston's Moses walking down from the

mountain holding the Ten Commandments, one which says “Thou Shalt Not Kill.” And

I went “Excuse me. Where am I? What planet is this”?

I know . . . .

What does Terrence feel about the death penalty?

I think he was already against it. His main interest in doing the story was to

take the whole discussion out of the abstract and put it into real life, with

people that we know. That's the brilliance of the whole story, and the

theatricality of it. It takes something that people only think of in abstract

terms – Yes I'm for it, yes, I'm against it – and puts it into very real terms.

When you see real people experiencing these things, it's a whole other issue.

What would you like people to know about this opera?

It's not an opera about the death penalty. Everyone thinks immediately it's an

opera about the death penalty, but nowhere in the opera is it even debated.

It's an opera about love and redemption; the death penalty forms a backdrop to

it because it tears at the core of it. It's about parents and children. It's an

opera about how love can transform and redeem your life. It's a very intimate

story with enormous forces at work behind it.

And it's not an opera that preaches. It's an opera that we hope takes people to

a place of reflection where they can make up their own minds about their

response. It doesn't tell you what to feel.

I neither read the book nor saw the movie? How close are we to them?

We're closer to the book. We based it on the book more than the movie.

However, there are choices we had to make that are made in the movie as well. In

the book, there are two different crimes and cases involving two different

people. Of course, you don't have time for that onstage; one is enough. So we

followed the movie's lead and combined elements of both to make it into one

case. There's no DeRocher in her book – he's an invented character, a composite

of both of them.

In our libretto, there's no question of DeRocher's guilt, right from the

beginning. In the movie, they left it vague until the end. In the book, Sister

Helen knew he was guilty from the beginning, even though in the second case he

was denying it until the end. That's sort of what our guy does, except that he

takes responsibility for his actions in the end. In her book, the second guy

didn't really take responsibility.

Have you made any revisions to the score since the premier?

We made changes during the rehearsal process, but not since. The way you hear it

on the recording is the way it will be performed all over.

In rehearsal, we cut a few little places – transitions that seemed too long when

they were on the stage – and adjusted the orchestration a little bit here and

there so things would balance right in the hall. These are things you can't tell

until you're actually in the theater.

The luxury was that Lofti had provided us with a workshop a year ahead of time.

So we had the chance then to fix up any dramatic or musical things that weren't

working. There wasn't a whole lot to change; it was pretty tight.

I believe at least five gay men were involved in the premier.

Oh yes. Me, Terrence, Joe Mantello the director, Patrick Summers the conductor,

and Michael Yeargan the designer. But it's opera; it's not unusual [Laughter].

Was there a special fellowship amongst you?

Certainly. There's always that. But there's never a problem in the opera world,

because it's sort of expected that a lot of the men are going to be gay. It's a

very unbiased profession. It's not about your identity as much as it is about

your ability to create the work.

There's certainly a different sensibility that we as gay men have had to find,

because we've had to deal with so much rejection and self-loathing that goes on

early in our lives. If you're strong enough to overcome it, certainly it makes

you a stronger, more sensitive, more open person.

I think every one of the people involved was at the point in their life that

they'd overcome all that stuff so that they were completely open and sensitive.

It was very easy to work with; it was never an issue.

There is a certain sense of camaraderie when you know the person, and know what

they've been through in part of their journey.

Orange County's production, the first since the SFO premier, is all new.

Yes. It's directed by Leonard Folia. Everything's different. The set from San

Francisco was too big to fit on most of the other stages. But since they all

wanted to do it, Orange County took the lead in getting seven companies to

co-commission this new production.

They decided too to create a whole other vision and see what would happen. It's

a very bold move.

Was the SFO production videotaped?

No, it wasn't. The documentary crew just took footage to use in their feature;

the entire production was not filmed. As for the new production, there are no

plans for a DVD at present.

[Jake is interrupted by the voice of a child]

Who's that?

That's my little boy. He's 6 and a half. My partner and I and Leslie, the mom,

are all family. Leslie has full custody, and Kurt my partner is the father.

They've always been good friends, and she really wanted a baby, so he was the

donor. When I came into the picture, she really welcomed me. We're very tight.

It's good.

You're also doing a song cycle of Sister Helen Prejean's poems.

Yes, for Susan Graham. It's just about done. It's a new set of texts called The

Deepest Desire, written for mezzo, flute and piano. It's going to be done at

Vail, Colorado this July. The flutist is Eugenia Zuckerman and I'm the pianist.

Are you going to record it?

Who knows (laughing). I just had a big piece done by Bryn Terfel in Carnegie

Hall, and a lot of people asked if he was going to record it. Your guess is as

good as mine. It's very difficult to get things recorded these days.

This is just what John Corigliano told me. He won the Pulitzer Prize for his new

symphony, and he doesn't know if it will be recorded.

That's the way it is these days. It's very sad, but it's a combination of

responsibility. The recording industry has insisted on recording old rep over

and over and over. We've taken music out of the schools. It isn't the

responsibility of a reviewer to praise something, but it is a responsibility to

render criticism in a way that people aren't just horrified and scared off. A

lot of time I read reviews and I think that if I didn't know a lot about

classical music, I wouldn't go near it ever.

Artists themselves have to take the initiative to go into schools and work with

young people, or it's just going to fade away.

Do you work with young people?

A lot. I just did some programs in New York with the Eos Orchestra. We went had

three sessions with the children. We took a story from the Iliad, reduced it,

musicalized it and performed it. Then, from the material the kids created, I

wrote a string quartet movement so they could hear the transition from pure

story to story with music to music, and they would know what the story line

process is. It was a very exciting.

I've also done many programs when I got into classes and speak to the kids. I

also do master classes, mainly for college students.

You've been the composer-in-resident for New York's famed Eos Orchestra for

almost two years.

Yes, that's ending this year. I was also resident composer for two years with

San Francisco. Now I'll be on my own for awhile.

And you have another commission for Houston Grand Opera. They keep commissioning

new works.

It's so great.

Are a lot of the companies you're working with experiencing financial

difficulties?

From the economic downturn following 9/11, it seems everyone had to change their

seasons around. They had to take away risky stuff and put in sure-fire box

office sellers so they can build their audiences back up and get back to where

they were. But I think the tide will turn again.

What music are you listening to these days?

I don't listen to music a whole lot at home. I find it very distracting to

listen when I'm at home, because I have to stay in that space in my head. But

what I've actually listened to recently, probably because I had the privilege of

meeting him, is a lot of the old Sondheim shows. I had never really listened to

Company or a couple of other things. It's a great opportunity to get to know

them.

He's a master. I think Sweeney Todd is right up there with the Mozart operas.

Of the original San Francisco cast, John Packard who plays DeRocher, and

Frederica Von Stade who plays his mother will perform in Orange County.

Kristin Jepson plays Sister Helen, as she did on the nights that Susan didn't

perform in San Francisco.

Will Susan appear in any other performances?

Yes, but it's in . . .

. . . the real exciting production of Dead Man Walking that you can't tell me about.

Is that because it's not definite?

It's definite, but the company is not ready to announce it. So I don't want to

jump the gun. It won't be for a couple of years.

What other singers are you writing for besides Susan?

Bryn Terfel has asked me to write something more for him. I'm also writing a big

set of songs for Flicka (Frederica Von Stade) and chamber orchestra, which will

be premiered by the Camerata Pacifica next year in Santa Barbara.

I'm writing the next opera for some really wonderful Australian singers: Cheryl

Barker, who just recorded a Butterfly in English for Chandos; Peter

Coleman-Wright, and Teddy Taju Rhodes, who was SF0's alternate Joe DeRocher. And

there's other stuff I'm not at liberty to talk about.

I just finished Susan's songs, and I'm working on a cello concerto which will be

performed by Emil Miland in the East Bay in November.

What would you like to say about the importance of music and classical music in

our lives?

I can't imagine life without music. I don't imagine any of us really can. When I

was working with these kids in this high school in the South Bronx, I asked them

when they heard music during the day. They'd say their radio and sometimes the

car. But I'd ask what about when you're in the store, watching TV, watching

movies? Music is essential to us as human beings. A world without it would be a

very bleak place.

Classical music, whatever that term means, is important because it delves even

further into the emotional realm and the stuff that makes us click as human

beings. It's about life and love, the only things that really matter. I can't

imagine a world without it.

- End -

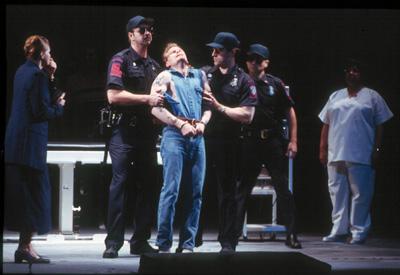

BARITONE JOHN PACKARD (Joseph DeRocher)

John Packard was in the midst of rehearsals for the new Orange County production

of Dead Man Walking when he took time out to discuss the opera and his

definitive portrayal. Unfortunately, the only time he had open for discussion

was unexpectedly cut short by a last minute rehearsal call. Nonetheless, we

managed to share a significant amount of information in our allotted 15 minutes.

Have you had major roles before playing DeRocher?

Not in a major house like San Francisco. I did Billy Budd in a new production in

Kansas City – it was just wonderful -- Valentin in Faust in a new production at

the Vienna Volksoper, and Marcello with Franco Zeffirelli in Israel.

Orange County marks your second production run of Dead Man Walking. Are you

scheduled for the other houses in the run?

Most of them, yes. It's going to be my major role for awhile.

What is it like for you to go into this character night after night?

When I first started working on the character, I wanted to separate myself from

him and come up with a façade. Unfortunately, or fortunately I would say, Joe

Mantello the director read right into it and said, “You're acting like a guy on

Death Row; you're not being a guy on Death Row. You have to go to that place

inside of you.”

I have to tell you, Jason, the first time we did the whole show all the way

through, the next morning I woke up sobbing. It's hard.

I think the role can be done without being inside of the character, but I don't

think it's as effective. I think you're kind of cheating yourself and the

audience of the full experience. So I can go into it with the idea of being Joe

DeRocher for three hours.

You have a wonderful voice. There's no question about that. And you look perfect

for part. I remember reading in the liner notes that when you walked onstage for

the audition, everyone thought you looked like a murderer.

It's not such a bad thing. It has actually launched my career in a different

way. It was going okay, but this just put the turbo boosters into my career.

It's allowing me to be heard by a lot more people.

There's always the worry of being typecast [laughing].

I suppose you could go around playing axe murderers for the rest of your career.

That's true, but I just did Sharpless in Madame Butterfly for Opera Company of

Philadelphia, and the woman playing Cio-Cio San said that I was the warmest

Sharpless she's ever worked with. So, it's acting. It's not just looks.

I used to only get comments on my singing when I was a lot younger. Now I get

even more comments on my stage presence and acting. I think that's great.

To get myself in the right frame for this interview, I did 50 push-ups. But your

onstage push-ups were more impressive. Did you work them up especially for the

role?

Before I was a singer I was really into bodybuilding. I'd be in the gym for

three hours four times a week. My body was trained enough that I could get right

back into it without going off the deep end.

Are you having to relearn a lot for this new Orange County production?

It's like throwing the score out and relearning it. The director has different

ideas for some of the lines. He takes me in a different direction, one that

makes the turnaround at the end even more impressive.

He's great. Everyone is really, really pleased with him. He really cares about

the production, and he cares about us, and he doesn't mind having fun every once

in a while. In San Francisco, we cried through the whole rehearsal period. There

were hardly any times when there was anything light. This is a nice change (not

that the production is light).

The Execution scene seems much shorter on disc than it was in the house.

I don't know. It seems really long when I am strapped on the table [laughing]. I

think seven seconds was how long each plunger took, and there were four of them.

That's not that long, but it seemed really long to me.

Did anyone involved in the opera witness an actual execution?

I don't think so. In order to do that, you have to be involved in some way with

the victims.

What do you want to say about the meaning of this opera?

We just did a death penalty symposium at UC Irvine. I was asked a similar

question about the death penalty.

A number of anti-death penalty professors had been to the movie and criticized

it for not making a statement or not being anti-death penalty – in fact for

coming across as pro-death penalty. When they asked me about the opera, I said

its purpose was not pro- or anti-death penalty; it was about entertainment.

Whatever affects you, that's what you take away from it.

I've had people in San Francisco come up to me and thank me for showing how the

necessary the death penalty is. They believe that DeRocher wouldn't have broken

down if death hadn't been looking him in the face. And I had other people say

that they were on the fence now; before they were leaning toward being against

the death penalty.

That's what art does. It makes people think. They'll think about the death

penalty, and how it affects everyone.

It's great how Jake has really put it across that everyone is affected by the

death penalty.

Nobody feels the opera the same way. That's what's so great about Dead Man

Walking. Some people will be unchanged, and others will be drastically changed

in the opposite direction. But in the end, the opera does not need to make a

statement.

What are your own views on the death penalty?

Personally, I am now anti-death penalty. I was pro, but I changed because of

working on this piece.

You said that opera is “entertainment.” I've interviewed several artists who

insist that classical music isn't about entertainment.

It is entertainment first. But when you experience it, you come away with a

different feeling.

You've just been called to rehearsal. What more do you wish to say about the

music itself?

Generally it's quite lyrical. There are some gorgeous moments. It's a dramatic

piece, somewhere between opera and musical theater. Actually, before Jake

started working with the real singers, it was more like musical theater, and now

it's more like opera.

- END -

- Jason Serinus -

![]()

© Copyright 2002 Secrets of Home

Theater & High Fidelity

Return to Table of Contents for this Issue.