Feature Article - Learning from History: Cinema Sound and EQ Curves - June, 2002 Brian Florian

A long time ago, in this very galaxy, we thrilled to a new and burgeoning cellulite art form called Motion Pictures.

Introduced to us in the very late 1800s, it was a crude but novel form of entertainment, yet thanks to the marketing savvy of old man Edison, it flourished and advanced. In its infancy, movies were black and white with no sound save for the nostalgic rifts of a piano player in the theater, wildly following the on-screen action in a somewhat successful attempt at boosting the mood of the scene.

While the introduction of color is an undisputed colossal advance for the medium, it is synchronized sound that goes down as being the most important evolution for film. The 1926 release of "The Jazz Singer", featuring a sound technology called Vitaphone, changed the way the world thought about movies, forever. In the first quarter of the 20th century, even movie executives are quoted as believing sound and film are not a worthwhile union, and some 50 odd years later, a certain movie maker coined the statement, "Sound is half the movie".

The Academy Optical Mono soundtrack and the Academy Curve are born

Initially,

in the mid 1920s, we saw many technologies

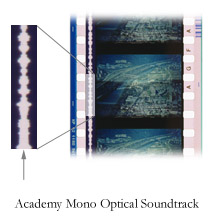

brought to the table, but during the 1930s, the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences established a standard for sound-on-film. A sliver of space to the side of the picture frame was home to an optical track through

which light was driven and picked up by a photo sensor. By varying

the width of the opening, the amount of light delivered to the photo cell

varies as the film passes, creating varying voltages in the sensor, and a soundtrack is

created. The basic principal of the Academy

Optical Mono soundtrack is still employed in part today.

Initially,

in the mid 1920s, we saw many technologies

brought to the table, but during the 1930s, the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences established a standard for sound-on-film. A sliver of space to the side of the picture frame was home to an optical track through

which light was driven and picked up by a photo sensor. By varying

the width of the opening, the amount of light delivered to the photo cell

varies as the film passes, creating varying voltages in the sensor, and a soundtrack is

created. The basic principal of the Academy

Optical Mono soundtrack is still employed in part today.

Technology advanced fast in the early half of the century, especially as it related to loudspeaker and amplifier technology. Thus was born a need for the industry to achieve a mechanism by which a soundtrack could be crafted and presented with consistency, regardless of the varied and widespread caliber of hardware it would encounter in a run.

Ideally, a sound system should have as flat a frequency response as possible. Reality in the 1930s was otherwise. In particular, while "better" theaters and studio mixing facilities exhibited "good" response, there existed an overabundance of movie theaters with poor high end response and an almost non-existent low end. In addition, the Academy Optical Mono track itself suffered from a curtailed high frequency response and an inherent hiss. The mechanical barrier of a perforated movie screen further filtered high frequencies.

Ultimately,

in 1938 the Academy mapped out the response of the "worst case" scenario of the

day, and the Academy Curve was born. Mixing stages and better theaters applied equalization to

simulate the poor response of lesser exhibition facilities, ensuring that they

were evaluating and crafting the soundtrack such as it would be heard by the

public. Thus was laid the foundation for standardization of soundtrack

presentation.

Ultimately,

in 1938 the Academy mapped out the response of the "worst case" scenario of the

day, and the Academy Curve was born. Mixing stages and better theaters applied equalization to

simulate the poor response of lesser exhibition facilities, ensuring that they

were evaluating and crafting the soundtrack such as it would be heard by the

public. Thus was laid the foundation for standardization of soundtrack

presentation.

The Academy Curve is also known as the Normal Curve and is defined as flat 100 Hz - 1.6 kHz, down 7 dB at 40 Hz, down 10 dB at 5 kHz, and down 18 dB at 8 kHz.

In layman's terms, this is a dramatic attenuation of the treble and a generous reduction of the bass.

Some technological advances in movie sound were made such as the 1940 release of "Fantasia" with its four channels of audio through a technology named 'Fantasound', but it was not until the 50s that the term "Stereophonic Sound" was understood by the pubic.

The advent of television was regarded as being a threat to the motion picture industry. The response from Hollywood was reinvention of the format, characterized by wide-framed (widescreen) film formats, the grandest of which are collectively recalled as 70mm. With the bigger picture came bigger sound. The 1953 film "The Robe" is recalled as the first CinemaScope release with four channels of magnetic sound right on the film strip, the technology being virtually identical to today's cassette or open reel tape. This landmark was quickly followed with "Oklahoma" whose ToddAO release featured six channels of magnetic sound (five channels across the screen and one surround). These events formed the catalyst for the development of six-track magnetic sound on 70mm film, a practice that would endure for decades.

Though these "mag prints", as they were called, exhibited dramatically improved fidelity, they were expensive to make, and the soundtrack, being an iron oxide coating applied to the film, did not hold up well to wear and tear. These factors ultimately lead to the demise of 70mm as a mainstream format and 35mm film returned, gaining the benefits of wide format shooting, but the audio was back to an unaltered and badly aging Academy Optical Mono soundtrack. Thank our lucky stars Dolby got interested in motion picture sound.

The second age of Cinema Sound: Dolby and the X-Curve

Naturally, speakers and other audio hardware improved as the decades marched on, but the optical soundtrack did not. Eliminating the Academy Curve would simply have exposed the inherent hiss which it masked.

When Dolby got involved with cinema sound in the 70s, the first thing they did was apply their noise reduction technology which was already well entrenched in the music industry. The 1971 "A Clockwork Orange" demonstrated to the world an improved bandwidth and high frequency extension thanks to Dolby's A-Type noise reduction. As a result, the world was finally able to give up the Academy Curve . . . but not for a flat response.

Research done a decade earlier by C.P. and C.R. Boner defined a need for a "house curve". They based this on the fact that a flat electro-acoustic frequency response in a large room sounds too bright on well-balanced program material. Or in simpler phrase, we perceive sound in a large room to have more treble.

Here stood an opportunity to put into place a curve system which could go beyond simply dictating a flat response, but also address the psycho-acoustic differences of sound in large, medium, and small theaters and mixing facilities. The �X Curve� was born.

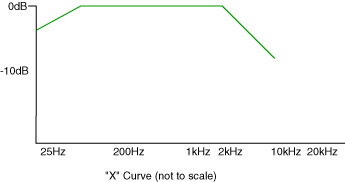

Also known as the wide-range or eXtended range curve, the X-Curve is defined in ISO Bulletin 2969

as pink noise, at the listening position in a dubbing situation or two-thirds

of the way back in a theater, to be flat to 2 kHz, rolling off 3 dB/octave after

that.

Also known as the wide-range or eXtended range curve, the X-Curve is defined in ISO Bulletin 2969

as pink noise, at the listening position in a dubbing situation or two-thirds

of the way back in a theater, to be flat to 2 kHz, rolling off 3 dB/octave after

that.

The measurement of EQ is done using wideband pink noise excitation through the

speaker. The larger the room, the longer and greater the reverberation buildup over

time, resulting from this steady-state signal. If we measure EQ on a fixed

bandwidth basis, like full octaves or third octaves, the reverb which tends to be

stronger at low frequencies will tend to make the SPL read louder there than

at the higher frequencies where it is better absorbed. By knowing how much the

meter reading is influenced by this effect, a curve can be used to compensate.

That's what the X curve does. Unlike the Academy Curve before it,

It has nothing to do with high frequency capability in the playback chain.

It turns out that while SPL meters are "stupid" and cannot

distinguish the flat direct speaker sounds from the room sounds which arrive commingled,

humans hear the true spectrum of the direct sound and interpret the room sound

as reverb or spaciousness. It's a bit more complicated than that, but you get

the idea. Small, deader rooms

need less and less of the full X-curve compensation, as they have less of the

meter-confusing reverb present.

So while we have the basic ISO definition of the X-Curve, it is fundamental to realize that there is in fact a table that contains variations to the curve based on room size. For example, there is a Small-Room X Curve, designed to be used in rooms with less than 150 cubic meters, or 5,300 cubic feet. This standard specifies flat response to 2 kHz, and then rolling off at a 1.5 dB/octave above 2 kHz. Some people use a modified small-room curve, starting the roll-off at 4 kHz, with a 3 dB/octave rate.

For almost 30 years, the X-Curve has provided the motion picture industry with a valuable standard that ensures plausible interchangeability of program material, from one studio to the next, from studio to theater, and from film to film, which takes into account the different perceived spectral response of different room sizes.

Its worth noting that in the same decade, Dolby also pioneered the concept of a calibrated playback level for mixing facilities and movie theaters. A reference-level pink noise piped through the audio chain was calibrated to 85 dBc (the "c" means the curve is "C Weighted", vs. "A Weighted", referring to the way humans hear different frequencies). With mixing facilities and theaters setting their master volume level by the same rule, the levels chosen by the film makers would be assured in the cinema.

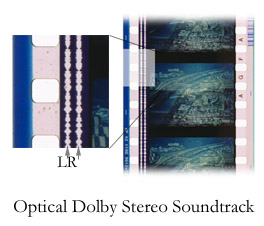

In 1977,

"Star

Wars" brought us not only a new genre of science fiction film, but a new sound format that

would impact motion pictures like no other. Dolby created a way to deliver

four channel

soundtracks optically on the film, addressing both cost and wear issues. Through their

experience with noise reduction technology, Dolby was able to put two optical

channels on the film in the space previously occupied by the Academy Optical

Mono track. They then 'folded' a center and surround channel into the left and

right optical tracks. When 'decoded' in the theater, the system yielded three screen

channels and one surround. The thrill of multiple screen channels and surround sound

was now within reach of the masses. By the mid

80s, virtually every commercial release featured four-channel Dolby Stereo sound. Even

today's digital soundtrack releases keep the Dolby Stereo soundtrack as a

backup to the digital track and to maintain compatibility

with older cinemas.

In 1977,

"Star

Wars" brought us not only a new genre of science fiction film, but a new sound format that

would impact motion pictures like no other. Dolby created a way to deliver

four channel

soundtracks optically on the film, addressing both cost and wear issues. Through their

experience with noise reduction technology, Dolby was able to put two optical

channels on the film in the space previously occupied by the Academy Optical

Mono track. They then 'folded' a center and surround channel into the left and

right optical tracks. When 'decoded' in the theater, the system yielded three screen

channels and one surround. The thrill of multiple screen channels and surround sound

was now within reach of the masses. By the mid

80s, virtually every commercial release featured four-channel Dolby Stereo sound. Even

today's digital soundtrack releases keep the Dolby Stereo soundtrack as a

backup to the digital track and to maintain compatibility

with older cinemas.

Despite extreme rarity, six-track magnetic sound on 70mm release prints was not dead in the 70s. Dolby's involvement with cinema sound would lead to their refinement of the decades-old magnetic sound system. It was noted that soundtrack artists had all but abandoned the middle two screen channels (left-center and right-center). Initially, in 1975, Dolby used those tracks to create a discrete subwoofer track, affectionately known in its day as the 'boom' track. By providing a separate segregated channel for a subwoofer system, the bass headroom of the system was greatly extended without taxing existing speakers and without any extraneous crossovers in the signal path. Then in 1979 they used the upper bandwidth of those same two tracks for stereo surrounds (left-surround and right-surround). The first feature film released with a Dolby Stereo 70mm soundtrack was the 1979 "Apocalypse Now".

Dolby continued to improve optical analog sound with Dolby Stereo SR (Spectral Recording). Introduced in 1987 with "Robocop", it brought the improved fidelity of Dolby's SR noise reduction to cinema sound, extending the dynamic range by 3 dB. Because the process for calibrating playback level remained the same, the extra headroom was exactly that: more head room, meaning better dynamics during explosive scenes.

By 1990,

digital audio was a household word. As has been a tradition since its inception,

the cinema kept pace. In 1992, Dolby unveiled the next generation of motion

picture sound with the release of "Batman Returns": Dolby Digital (a.k.a.

Dolby Stereo SR-D).

Modeled on the Dolby Stereo 70mm format, Dolby Digital features three front screen channels,

two rear

surrounds, and one LFE (Low Frequency Effect) track. The sound is digital and all channels are discrete,

meaning that each channel is a discrete or separate track in the recording,

rather than the rear channel and front center channel having to be extracted

from two stereo channels like it is with Dolby Pro Logic.

Even more important, it is optically printed on inexpensive, ubiquitous 35mm release prints,

and thanks to Dolby AC-3 compression technology, it fits on the film without

taking space away from either the existing Dolby Stereo optical soundtrack, or the picture

itself (DD is stored in between the sprocket holes on the film). High quality, digital multi-channel sound was now within reach of

the masses. Today, just about every commercial movie release features a Dolby Digital

Soundtrack.

By 1990,

digital audio was a household word. As has been a tradition since its inception,

the cinema kept pace. In 1992, Dolby unveiled the next generation of motion

picture sound with the release of "Batman Returns": Dolby Digital (a.k.a.

Dolby Stereo SR-D).

Modeled on the Dolby Stereo 70mm format, Dolby Digital features three front screen channels,

two rear

surrounds, and one LFE (Low Frequency Effect) track. The sound is digital and all channels are discrete,

meaning that each channel is a discrete or separate track in the recording,

rather than the rear channel and front center channel having to be extracted

from two stereo channels like it is with Dolby Pro Logic.

Even more important, it is optically printed on inexpensive, ubiquitous 35mm release prints,

and thanks to Dolby AC-3 compression technology, it fits on the film without

taking space away from either the existing Dolby Stereo optical soundtrack, or the picture

itself (DD is stored in between the sprocket holes on the film). High quality, digital multi-channel sound was now within reach of

the masses. Today, just about every commercial movie release features a Dolby Digital

Soundtrack.

With the Optical Stereo track still in use as a backup track, Dolby Digital blew the doors off dynamic range, extending it to 105 db (the difference between the softest and loudest sound is 105 dB). Again, the calibrated level process remained the same, so ultimately Dolby Digital gave the film-maker more volume at the top end. Unfortunately this headroom has been more abused than used. You can read all about it in the excellent paper by Loan Allen of Dolby Labs entitled "Are Movies Too Loud?"

What does all this mean for us at home?

Although rare, there are old, classic films with their mono soundtrack intact on home video and could use the high frequency attenuation of the Academy Curve. Several of what are thought to be the better surround sound processors offer such a filter, and I routinely encourage others to follow suite. In the digital audio age, the cost is relatively minimal, and given that the Academy Curve brings with it no controversial stigma, it's a nice tool to have around.

Since the advent of Dolby Stereo though, the soundtrack of virtually every movie (be it Analog or Digital) is crafted for playback over a system equalized to the X-Curve and set at the reference playback level. Unfortunately there is no entry in the X-Curve table for rooms as small as most home theaters, and even if there were, like theaters and studios, you'd need 1/3 octave equalization on each channel to conform. Don't worry. Read on.

If you could get your hand on the X-Curve table, one corollary would stick out for you: As the rooms get smaller, less and less of a roll-off is defined, because as we said, smaller rooms have less of the reverb which the X-Curve addresses.

By the time we shrink a room down to typical home theater size, we can say that no X-Curve compensation is needed, much to the contrary of popular opinion. There is not an inherent overabundance of treble in motion picture soundtracks, at least not due to the X-Curve.

In 1988, the George Lucas company THX, which previously had established elevated standards for motion picture presentation, entered the consumer electronics market with its THX Home Theater Program. Among the program's many facets were new and proprietary processes for THX surround sound processors, including one called Re-EQ.

Re-EQ is a filter applied to soundtracks after Pro Logic or AC-3 decoding. Although developed using the X-curve as a reference, it is not an X-Curve per s�, but a rational choice of filters that address the common (and in my opinion true) perception that film soundtracks played at home are typically too �bright� (too much high frequency). However, as we've said, the fact that the soundtracks were mixed for an X-Curved presentation has nothing to do with it. While hunting for an X-Curve compensation, which technically should not be required, THX developed a filter that aptly addresses other issues in home theaters.

The factors which make home theaters sound subjectively "too bright" are varied and numerous, and no two home theaters are going to be the same in this regard. Home theaters are usually more reverberant than studios, cinemas, and dubbing stages, sustaining high frequency energy much longer, despite their small size. The speakers are often much brighter than properly set up theater arrays. As we push the playback level up towards reference level, the problem gets worse. If a system is genuinely capable of high output with low distortion, then it is possible to recreate the " movie theater experience" and enjoy it. Unfortunately, there are far, far fewer systems capable of this than we are lead to believe. Many so call high-end speakers and many receivers exhibit harmonic buildup at high output and tilt the spectrum in favor of the treble, further exacerbating the brightness problem. Just because you paid a lot for it does not necessarily mean it is suitable for reference level movie playback. Sorry.

We must also consider that the perception of film soundtracks being too bright in home theaters has perhaps less to do with the spectral balance of the recording, dubbing or home theater systems, and more to do with heavy handed and ill chosen mix techniques used during the mix process. With such mixes, Re-EQ can�t correct anything but can make it easier to listen to, one of many reason I'll continue to want it on my processor.

THX chose an X-Curve type filter since their listening tests show that it�s more likely to produce an accurate correction more of the time. Of course, playback systems and film transfers are sufficiently variable that a single curve is never going to be �correct� all of the time. It is not intended as an absolutely correct interpretation. As with everything THX does, they look at the consumer's reality, the realities of the Consumer Electronics industry and the available technical tools, and then create a solution that makes rational sense for most consumers most of the time.

We've often been asked the question, "Why not just remix the soundtrack or apply a form of filter to it when mastering the home video?"

While a noble sentiment, it does not eliminate the need for Re-Eq, because we still would have an existing archive of home video material that needs it. Looking forward, given the variable in playback systems, there is, in the opinion of some, little utility in applying a filter in the transfer process (from cinema master to home video master). It�s an extra step and 80% (or so) of DVD viewing systems are operated well below reference level such that a bit too much HF energy goes unnoticed. At the same time, we are seeing an ever increasing number of titles whose soundtracks are in fact "redone" for home theater (most noteworthy are recent titles from New Line Cinema). These come with the stigma that Re-Eq is not required or appropriate.

The problem we face right now is one of trial and error: When we take that new release DVD rental home, will it be better served by having Re-Eq on or off? Who knows? We as consumers have very little to go on in this regard other than our own ears. THX (naturally) advocates the status quo with Re-Eq, in place while other industry professionals openly advocate remixing the soundtracks.

No one ever said being a home theater aficionado would be easy.

When the ATSC* chose Dolby Digital AC-3 as the audio format for HDTV, among

other things they defined a 2-bit flag called "Room Type" which is said to

define the type of mixing room the material was made in. The flag can be

set as follows:

00 not indicated

01 large room, X-curve monitor

10 small room, flat room monitor

11 reserved

Contrary to some opinions, this flag is not meant to be a "Re-Eq on/off" signal. If the correct X-Curve was properly implemented in the studio, it should make no difference, at least in terms of EQ in a "good" home theater (one which does not sound too bright).

Like many of the flags in AC-3, this one exist more as a "just in

case" thing. It's not actually read at this time by any consumer

decoder, and the ATSC standard does not really define how it should be used

anyway (according to my source; I have not actually seen the document).

Some features like this just never get used. AC-3

originally had a full suite of language codes, but these were never used since

MPEG transport and program streams already carry this info (such was not

certain at the time the AC-3 spec was written). Maybe one vision

for the "Room Type" flag was to one day trigger "large room

simulation" DSP programs to help recapture the large room experience,

more like what was heard by the mixer.

Conclusion

The lesson to glean from the movie industry's experience is that "the room" plays a huge role in what is realized from a playback system.

While the X-Curve puts all the commercial facilities on the same page, there's no real way to account for different reverb characteristics, since even rooms with identical Rt60** measurements can still sound different due to a different spectrum of absorption. How do they finally decide the room is right or not after EQ adjustments have been performed if X-curve can still allow for some subjective variability? The answer is, listen to it with familiar reference material. Does the system sound right, bright, or dull? If it is one of the latter two, further adjustment of EQ, acoustics, or other properties may be necessary.

I've always advocated Re-Eq and will continue to do so, but not because it is a fix for the X-Curve. In my opinion, typical home theater spaces with typical home theater hardware playing typical contemporary material do sound too bright, and Re-Eq is a simple and effective fix most of the time. Because that's a "most" and not an "all", I'm also big on processors that allow it to be engaged or disengaged independently of the other THX Post Processes.

Ultimately, I would like to see enthusiasts spend more time and energy on their room configuration, at least as much as they do on selecting their components.

Doing acoustical treatments in a home theater is the equivalent of applying an X-Curve in a commercial or professional facility. While we don't have 1/3 octave EQ and a curve to shoot for, we can still fine tune our rooms to sound "right". A little absorption here and some diffusion over there can make a monumental difference in a room.

After all, a modest system in a "good" room can easily outperform upscale,

expensive equipment in a bad one.

- Brian Florian -

I thank Roger Dressler of Dolby Laboratories for his contributions to this article.

* ATSC - Advanced Television Systems Committee

** Rt60 is an acoustical measurement used to calculate reverb time decay, and in basic terms, is the measurement of time it takes a signal to decrease by 60 dB.

![]()

� Copyright 2002 Secrets of Home Theater

& High Fidelity

Return to Table of Contents for this Issue.