|

|

|

|

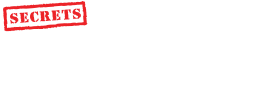

Mark O'Connor's Hot Swing Trio

In Full Swing

Featuring Wynton Marsalis and Jane Monheit

Sony Odyssey SK 87880

|

|

0 |

5 |

|

Performance |

|

|

Sonics |

|

|

|

At 41, Mark

O'Connor's reputation as a first-class jazz/folk violinist and versatile

composer is assured. "In Full Swing", released to coincide with O'Connor's Hot

Swing Trio's January through May U.S. tour – including a prestigious

February performance with Marsalis and Monheit at Jazz at Lincoln Center –

confirms that, in many ways, O'Connor is the rightful successor to his

teacher and “biggest violin hero,” famed French jazz violinist Stephane

Grappelli.

It's not that they have the same sound. A romp through a modest sampling

of Grappelli's hundreds of recordings, made over a span of more than 50

years, reveals an artist whose technique is as light on its feet as his mind

is quick to improvise. The sound is more Old World than new: glistening,

sometimes silvery thin, occasionally a bit edgy, but always viscerally and

emotionally gripping – a sound reminiscent of that produced on the classic

recordings of Bohemian and gypsy violinists. O'Connor, in turn, sounds more

polished, more “modern.” At least as heard on this disc, his tone is

smoother, fatter, and impeccably accomplished. That he plays an 1830s

Vuillaume violin with Zyex strings, and that his fingers seem nearly as

agile as Grappelli's, certainly helps.

The members of the group have very different backgrounds. Paris-born Grappelli, the son of

a philosophy teacher of Italian origin, originally made his living playing

Mozart on the piano as accompaniment for silent films. O'Connor, in turn,

whet his feet in the American folk tradition, and was as influenced by Texas

fiddler Benny Thomasson as by the Parisian jazz master. Grappelli may have

jammed with violinist Yehudi Menuhin, but O'Connor has premiered his Double

Concerto with violinist Naja Salerno-Sonnenberg, made a number of

Appalachian recordings with cellist Yo-Yo Ma and bassist/composer Edgar

Meyer, and seen the recent premiere of his a cappella Folk Mass written in

commemoration of 9/11.

In Full Swing is a ten-cut, 57-minute tribute to the Quintette du Hot Club

formed by Grappelli and gypsy guitarist Django Reinhardt in Paris in the

middle of the 1930s. O'Connor composed the foot-tapping title cut and the

“Stephane and Django” tribute; all but two of the other selections are

arranged by him. Many are expectedly upbeat, others, such as “Misty” and “As

Time Goes By” are in a slow, lyrical vein.

O'Connor and his fellow trio members, guitarist Frank Vignola and bassist

Jon Burr, are wonderful musicians. Just listen to how beautifully O'Connor

plays beneath and around sensational vocalist Jane Monheit on J. Burke's

“Misty.” When Monheit sings “a thousand violins begin to play,” one cannot

help but smile at the 1000 twists and turns that O'Connor brings to his

fiddling.

Monheit's vocals on four of the selections, including a solo on Gershwin's

“Fascinating Rhythm,” are alone worth the price of admission. Equally superb

is trumpeter Wynton Marsalis, who solos on “Tiger Rag” and joins Monheit and

crew for Fats Waller's “Honeysuckle Rose” and Braham's “As Time Goes By.”

This disc is a delight from start to finish.

|

|

|

Robert Schumann: String Quartets Nos. 1 and 3

The Zehetmair Quartet

ECM New Series 289 472 169-2

|

|

0 |

5 |

|

Performance |

|

|

Sonics |

|

|

|

Founded in 1997 by

Salzburg-born violinist and conductor Thomas Zehetmair, the Zehetmair

Quartet frequently receives rapturous reviews for their playing. Led by the

41-year old Zehetmair, whose discs of Beethoven and Szymanowski Violin

Concertos have received international recognition, the Quartet has recently

appeared on PBS-radio's Performance Today and completed a 10-day whirlwind

U.S. tour that included Washington DC, Dallas, New Haven, Chicago, New York

City, and Vancouver. On April 28, Zehetmair will join pianist Mitsuko Uchida

for a dual recital in New York City.

The Zehetmair Quartet's interpretive gifts are amply displayed in their

just-released ECM recording of Robert Schumann's String Quartets No. 1 and

3. Schumann wrote all three of his string quartets in the summer of 1842,

two years after he had celebrated his marriage to his young bride Clara by

composing no less than 138 songs. Romantic to the core, the quartets, spill

over with soaring melodies, surges of passion, and the characteristic swings

between ecstasy, heartfelt tenderness, and pathos that reflect, not only the

emotional landscape of romantic composers, but also Schumann's particular

state of manic-depression. It was in fact shortly after composing the

Quartets that Schumann's mental condition further deteriorated, to the point

where, with the assistance of Clara and his friend Johannes Brahms, he

eventually had himself committed to the sanitarium where he lived out the

remainder of his life.

The Zehetmair's interpretation of Schumann's gorgeous First Quartet in A

minor emphasizes its emotional jaggedness. Playing all but the first

movement faster than a competing recording by the Eroica Quartet (Harmonia

Mundi), and the entire work considerably faster than the St. Lawrence String

Quartet (EMI), the Zehetmair's tight sound contrasts with the lusher

performances of the other ensembles. In the Zehetmair's hands, Schumann's

music doesn't simply soar and sigh; it jerks from one melodic idea to

another, as though it romantic ripeness conceals an instability that cannot

help but surface. While there is certainly something to be said for the

warmer, riper sound of the other groups, the cumulative effect of the

Zehetmair Quartet's interpretation, especially their brisk concluding 5:33

fugal Presto (which they play almost a minute and a half faster than the St.

Lawrence String Quartet), is to leave the listener on the edge of their

seat.

Schumann's Third Quartet, like the First, abounds with song-like melodies,

their variations reminiscent of the manner in which Schubert developed some

of his most memorable melodies, e.g. “The Trout” (“Die Forelle”) and “Death

and the Maiden” (“Der Tod und das Mädchen”) into unforgettable chamber music

masterpieces. In the Third, the Zehetmair's bracing interpretation radically

outpaces competing versions, with several movements performed almost a

minute faster. Listening is aided by ECM's customary atmospheric sonics, and

a complement of authentic instruments crowned by Zehetmair's Stradivarius.

|

|

|

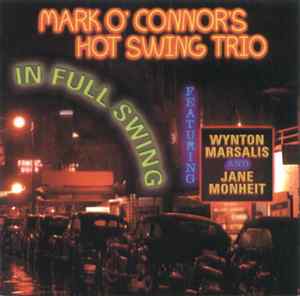

The Call of

the Phoenix

The Orlando

Consort

Harmonia

Mundi 907297

|

|

0 |

5 |

|

Performance |

|

|

Sonics |

|

|

|

They call themselves “the boyz.”

If only all the boys on the block made sounds as beautiful as these.

The four men of the a cappella Orlando Consort assembled in 1988 at the

impetus of the Early Music Centre of Great Britain. Initially formed to

perform repertoire from the years 1050 to 1500, their recordings have so far

brought them a prestigious Gramophone award, a slew of award nominations,

and a tour schedule that includes the U.S. in November and January.

The reasons for the consort's success become immediately apparent from the

first cut of this generous 18-track disc. Performing rare 15th century

English church music, the men offer a clarity of diction, rhythmic vitality,

and sheer beauty of sound that makes the sacred character of their music

thoroughly convincing. This is singing so polished and so filled with

veneration that its hymns of praise, mainly to Mary, truly lift the spirit.

Especially outstanding are the voices of countertenor Robert-Harre Jones and

tenor Charles Daniels, both of whom are known from their work with The

Tallis Scholars

The music on "The Call of the Phoenix" was written during the development of

the contenance angloise, the period in English music between 1420 and 1500

prized for its fluid polyphony and systematic consonance. The writing is

distinguished by a much smoother, more suave sound than that heard in the

earlier writing of the Middle Ages. Thanks to the disc's intelligent

programming, the development of the contenance angloise can easily be traced

in the changes of style between John Dunstaple's “Salve scema” and Walter

Lambe's “Stella celi.”

In the next year, the Orlando Consort will follow the lead of the Hilliard

Ensemble by collaborating with the jazz quartet 'Perfect Houseplants' and

the contemporary Dutch ensemble, The Calefax Reed Quintet. If you cannot

catch them live, Harmonia Mundi's customary superb recording technique

delivers a sonically convincing sampling of their vocal beauty.

|

|

|

ADonizetti: Lucie de Lammermoor

Dessay, Alagna, Tézier

Orchestre & Choeur de l'Opéra National de Lyon, Evelino Pidò

Virgin Classics 7243 5 45528 2 3

|

|

0 |

5 |

|

Performance |

|

|

Sonics |

|

|

|

With few new

complete opera recordings appearing these days, the release of a new version

of Donizetti's classic tale of love and madness is cause for excitement.

That Virgin offers for the first time Donizetti's 1839 French revision of

his 1835 Italian Lucia (now Lucie) arouses even greater interest.

Donizetti made many changes to his score before the French premiere. Not

only are the roles of the chaplain Raimondo shortened, and that of Lucia's

maid Alisa cut entirely, but music for other characters and scenes is also

revised. Most striking are the omissions of Lucia's Act I cavatina “Regnava

nel silenzio,” her Act II scene with Raimondo, and several orchestral

episodes; some of Lucia's (Lucie's) coloratura is also simplified. This may

not sound like a big deal, but when opera queens expect necklaces of

diamonds and instead receive strands of pearls, disappointment is the order

of the day.

The cast, headed by French coloratura soprano Natalie Dessay and EMI's tenor

hope of the decade, Roberto Alagna, promises more than it delivers. Dessay

has cancelled many performances in the last twelve months, with ill health

and vocal problems variously cited as the cause. Recorded in January 2002,

she certainly sounds in good vocal estate. But compared to some of our most

lauded Lucias of the last half-century, Dessay comes up wanting. It's not

that her voice isn't beautiful and her top solidly in place; rather, her

emotional commitment, as well as her phrasing, seem more generalized than

inspired.

One has only to listen to recordings by any of Dessay's “rivals” to discover

what is missing from her interpretation. Beverly Sills' Lucia (Rudel cond.),

recently remastered on Westminster, remains the most imaginative of the lot.

Wonderful throughout, Sills' brilliant use of rubato, shading, iridescent

tone, and coloratura display truly suggest a descent into madness. She may

possess neither the glorious, shining E flat nor the ravishing trill of Joan

Sutherland (Bonynge cond), but Sills' response to Donizetti's score is so

alive that no one in their right mind will complain. Callas, heard in her

famed 1955 live performance conducted by von Karajan, also astounds with a

combination of vocal instability, feather-light runs, deeply felt pathos,

and steely, solid high E flats.

Each of these women is supported by a conductor more imaginative than

Evelino Pidò, who frequently makes Donizetti's tunes sound more um-pah-pah

than need be. (When a melody is admittedly pedestrian, note how Bonynge

whips through it with excitement). Also disappointing is tenor co-star

Roberto Alagna. Alagna certainly has the notes and commitment, but his

throatiness and occasional gruffness show sorry evidence of singing too many

heavy roles. Alongside Callas' thrilling di Stefano, Sutherland's

gloriously-voiced Pavarotti (in her second recording), and Sills'

accomplished Bergonzi, Alagna delivers a performance more dutiful than

memorable. Listening to Sills, Sutherland and Callas in ensemble,

specifically in the famed Sextet, the vocal superiority of their co-stars

and conductor, combined with the greater satisfaction afforded by

Donizetti's Italian version, instills renewed fondness for their classic

recordings of Donizetti's masterpiece.

|

|

|

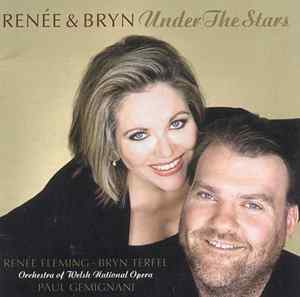

Renée Fleming & Bryn Terfel: Under the Stars

Orchestra of Welsh National Opera/Paul Gemignani

Decca 289 473 250-2

|

|

0 |

5 |

|

Performance |

|

|

Sonics |

|

|

|

Attention justifiably turns to

this major label disc of Broadway solos and duets. Sung by two of the most

sought after opera singers on today's stages, soprano Renée Fleming and

bass-baritone Bryn Terfel, the compilation offers such a contradictory

mixture of gorgeous vocalism and over-the-top histrionics as to give new

meaning to the well-worn saying, “there is no accounting for taste.”

Terfel is marvelous. A bear of a Welshman who is famed for larger-than-life

portrayals, the artist's ability to aurally swell in size while

simultaneously supplying more of the vocal beauty he emits in soft passages

is extraordinary. He's also a natural in show tunes, the occasional

overemphasis his largess of character lends to words in a Schubert song more

often than not appropriate for the popular idiom. Terfel's natural, unforced

diction is especially laudable.

Soprano Fleming certainly impresses vocally. Given that this disc comes on

the heels of her Grammy-nominated Bel Canto recording of coloratura gems,

graced as it is by multiple high E-flats and perfectly executed trills, she

astounds by sounding equally rich and beautiful in her low register. What is

at the least off-putting, however, and too often appalling is her sometimes

syrupy, afternoon soap opera crooning, especially when wed to frequently

self-conscious enunciation that has not entirely freed itself from the realm

of operatic English.

If you have ever thought than Mandy Patankin was over the top, wait until

you hear Renée. You may be won over by Bryn's initial voicing of “Nothing's

gonna harm you” on Stephen Sondheim's “Not While I'm Around” from Sweeney

Todd, but you're likely to feel the axe fall when Renée chimes in with

“No-one's gonna hurt you.” Especially frightening is her solo rending of

Rodgers and Hammerstein's “Hello, Young Lovers” from The King and I. Is this

the evil Witch of the West trying to fool us into thinking she's the real

thing? And when Renée begins the disc's Stephen Sondheim medley from Passion

with “I wish I could forget you,” you may find yourself nodding in

agreement.

Don't get me wrong. There's no absolute reason why you should avoid this

15-track compilation that travels from the peaks of Cole Porter to the

swamps of Andrew Lloyd Weber. Fleming and Terfel are fine artists, with some

of the most appealing, well-recorded voices you're likely to encounter.

Their total commitment, enhanced by orchestral arrangements perfectly suited

to their interpretations, is quite impressive. It's just that Hallmark's

most soupy offerings seem demure in comparison to some of these artists'

most egregious excesses.

|

|

|

Turnage: Fractured Line Etc.

Evelyn Glennie, Peter Erskine, Christian Lindberg

BBC Symphony Orchestra, Leonard Slatkin

Chandos CHAN 10018

|

|

0 |

5 |

|

Performance |

|

|

Sonics |

|

|

What a racket! The opening of

Another Set To for trombone and orchestra, the first of four premiere

recordings on this disc, wastes no time in voicing one of its main themes, a

“waah, waah, waah” kind of splatter that seems a perverse cross between a

howling infant and a maddening taunt proffered on a children's playground.

Trombonist Christian Lindberg may very well be, as declared by the

international readership of The Brass Bulletin, one of the ten greatest

brass players of the twentieth century, a man whose artistry has inspired

composers of the status of Schnittke, Xenakis, Berio and Takemitsu to write

concertos for him. (Over seventy concertos and a great many solo works have

been composed for Lindberg). Nonetheless, that does not make this piece of

music, nor any of the other three pieces on the disc, easier to listen to.

Many listeners will groove to the music of British composer Mark-Anthony

Turnage (b. 1960). It's large scale, hard-edged, reminiscent of much

cacophonous jazz, and frequently dark. Certainly it attracts star soloists

and conductors. Evelyn Glennie, heard hear joining percussionist Peter

Erskine for Turnage's Double Percussion Concerto “Fractured Lines,” is the

first percussionist to successfully sustain a full-time solo career.

Glennie's twelve solo CDs, seventeen collaborative discs, two Grammys, and a

Classic CD award have helped generate over 100 performances a year. She has

in fact stated that if she had to take one instrument to a desert island, it

would be the snare drum. It's thus no surprise that someone with this view

of paradise would find herself drawn to Turnage's darkly sensational,

anything but sedate music.

Erskine began his career at the age of eighteen with the Stan Kenton

Orchestra, and has since played with Weather Report, Ensemble Modern, the

BBC Symphony Orchestra and the London Symphony Orchestra. He leads his own

trio, tours extensively, and has recorded 400 albums, one of which won him a

Grammy. As for the distinguished BBC Orchestra, it will devote this year's

annual composer weekend to the music of Mark-Anthony Turnage, the

Orchestra's Associate Composer.

None of this, however, changes the fact that my partner's pooch, the

estimable Baci Brown, found himself more comfortable retreating to the

kitchen when Turnage's music began to fill my living room. Maybe he's been

fed too much Mozart, Schubert, and Donizetti of late.

This 56-minute CD contains a fine essay and revealing interview with Turnage

that provide much insight. For example, the composer says of the annoying

Another Set To that while it's “quite argumentative… the thing I'm pleased

about is that compared with a lot of my pieced it's optimistic and

extrovert.” Optimism comes in many forms.

Elsewhere you'll learn that Four-Horned Fandango has been heavily revised

since it was first performed by the horn section of the City of Birmingham

Symphony Orchestra under Simon Rattle in celebration of EMI's 100th

birthday. Silent Cities for orchestra, a revised version of variants

surrounding a tune by John Scofield that were originally composed for the

Tokyo Philharmonic Orchestra, begins with a section titled “Nagging and

obsessive.” It may end “Smooth and serene,” but the nagging impressed me the

most.

To summarize: impressively tailored music, definitively performed,

challenging for some, satisfying for others, definitely worth exploring.

|

|

|

Dvorák: Piano Quintets in A, Op. 5 & Op. 81

Ivan Klánsky - Prazák Quartet

Praga PRD 250 175

|

|

0 |

5 |

|

Performance |

|

|

Sonics |

|

|

Thoughts of

Czeck composer Antonin Dvorak (1841-1904) inevitably summon forth

expectations of felicitous melodies that flow forth like fresh, sparkling

water from a deep and abundant source. Known for assimilating the “dumka,”

“polka,” and other Slavonic folk dance idioms into romantic classical forms,

Dvorak was so adept at reflecting the popular heartbeat of a region that he

was able, during his brief stay in America, to compose his somewhat

convincing, and unquestionably beautiful, “New World Symphony” and

“American” String Quartet.

Dvorak wrote two piano quintets, both in the key of A. The first, his Op. 5,

was composed in 1872, at a time when he was playing viola in the Prague

Provisional Theatre Orchestra. It was only after 1876, when Brahms

discovered him and the orchestra's conductor Bedrich Smetana championed his

works that Dvorak began to become known beyond Czechoslovakia and to develop

a mature style of composition.

The original first movement of the early quintet reflected the influence of

Wagner. Dvorak abandoned the work shortly after its premiere, eventually

misplacing the original manuscript. It was only in 1887, after obtaining a

copy from a music critic, that he created the revised version heard on this

recording. In the process, the composer eliminated over 170 bars of music,

including 150 Wagnerian-influenced bars in the first movement. Though he

never published his revision, the project inspired Dvorak to compose another

Piano Quintet in A, his Op. 81, in the same year. Considered a masterpiece

of romantic composition, it is this piano quintet that is most frequently

programmed in concerts.

Dvorak's music comes naturally to the Czech forces heard on this recording.

The Prazak Quartet was founded in the mid-1970s by four students at the

Prague Conservatory. After winning important competitions in 1978 and 1979,

the newly graduated musicians embarked upon a career as a professional

quartet. Known for their mastery of the music of Czechoslovakian composers

-- they have made multiple recordings of works by Dvorak, Smetana, Suk,

Novak, Janacek, and Schulhoff -- they are equally respected for performances

of the Second Viennese School (Schoenberg, Berg, Webern, and Zemlinsky) and

their predecessors (Haydn, Mozart, and Schubert). The Quartet is currently

completing a five-year recording project of Beethoven's String Quartets.

Joined herein by Czech pianist Ivan Klansky, the musicians deliver

exceptionally winning performances. From the opening notes of the Op. 81

Allegro, whose first theme is a classic song-like melody that, once heard,

cannot be forgotten, the men seem to have Dvorak's music in their blood.

They understand the romantic give and take of his writing, alternately

bubbling along sweetly and surging with the melodic flow in a consistently

musical manner that maintains the classical line.

Flattered by a natural, warm acoustic, the Prazak's rendition of Op. 81

certainly has the edge over a rapidly dispatched, edgy digital transfer of a

1975 performance featuring famed Czech pianist Rudolf Firkusny and the

Juilliard String Quartet (Sony Essential Classics), and a much slower,

sometimes soppy 1990 Firkusny remake with the Ridge Quartet (RCA) that

boasts a wide but one-dimensional soundstage. The warmth of the piano and

cello are balanced by a sound that is simultaneously sweet and, in its

romantic expression, a welcome throwback to an earlier era.

The Prazak Quartet has devoted November 2002 and February-March 2003 to

touring the United States. With appearances including New York's Carnegie

Hall, Berkeley's Zellerbach Hall, and a Chamber Music Festival in the Napa

Valley, they ended their tour with two mid-March appearances in Costa Mesa

and La Jolla in Southern California. The all-Czech program heard in many of

these venues featured Smetana's My Country, Martinu's String Quartet No. 7,

and Janacek's String Quartet No. 2 “Intimate Letters.”

|

|

|

Schubert for Two: Gil

Shaham/Göran Söllscher

DG 289 471 568-2

|

|

0 |

5 |

|

Performance |

|

|

Sonics |

|

|

Eyebrows may

raise at the sight of Schubert's instrumental and vocal music arranged for

violin/guitar duo. But if we have come to accept Bach's music arranged for

every instrument known to humankind, why not give Schubert's a try on

guitar, accordion, or whistle?

This is not a collection of the profound Schubert, music that reflects his

early knowledge of impending demise from the syphilis he contracted while

still a teenager. Rather, it mostly offers a taste of Schubert's sweeter

fare, a slice of a composer light on his feet. That "Schubert for Two" has

"pleasant classical FM programming" written all over it does not in itself

diminish its musical value.

There is sound musical precedent for some of the arrangements on this 16

selection CD. The disc's longest piece (25:30), Schubert's famed

three-movement "Arpeggione" Sonata D 821 (1824), was composed so that one

Vincenz Schuster would have something to play on his arpeggione, a hybrid

instrument invented in 1823 by Johann Georg Stauffer that is a cross between

a guitar and a viola da gamba. With its six strings tuned an octave lower

than the guitar's, the arpeggione was held between the knees and bowed like

a cello. Though the Arpeggione Sonata is usually arranged for either

viola/piano or cello/piano, hearing it played on violin and guitar curiously

takes it one step closer to and another step away from the work's authentic

roots.

Schubert's publisher Diabelli originally issued the 15 German dances D 365

in an arrangement for flute or violin and guitar. Whether Schubert made or

sanctioned the arrangement, we do not know. But we are certain that Schubert

played the guitar, published a number of his songs with guitar

accompaniment, and composed a Quartet for flute, guitar, viola and cello

(Koch).

Shaham sounds marvelous. The man, who brought the entire Davies Symphony

Hall audience to its feet a year ago when he joined Michael Tilson Thomas

and the San Francisco Symphony for a stupendous performance of Beethoven's

Violin Concerto, here plays far more simply. His Stradivarius' sound remains

"old world" in the richness of its lower notes and incomparable sweetness on

high, but the playing, with minimal vibrato, is distinctly modern. Shaham is

at his most touching in the Arpeggione's lovely central Adagio.

Although Shaham's violin, provided far more resonance than the guitar,

dominates the proceedings, Söllscher's modern instrument is well captured,

if not with the last ounce of veracity heard on a recent Grammy-nominated

disc of the Los Angeles Guitar Quartet (Telarc). Neither violin nor guitar

can approach the emotional range of voice and piano in the program's two

songs, the famous "Standchen" (Serenade) and "Ave Maria."

All said, ideal for tea for two or dessert, if not as major fare.

(To see details

on my procedure for reviewing music, click

HERE.)

- Jason Serinus

-

Terms and Conditions of Use

|