“Lost sounds found.” That was the marketing slogan that Vinyl Me, Please employed when I joined the club a couple of years back. The idea being, at least theoretically, that they turn listeners on to music that may have slipped past their radar upon initial release. I just glanced at their website to see if the little mantra is still in use, and it appears to have gone the way of high-quality vinyl pressings. That is to say, it’s in a graveyard sharing a shaded plot on a grassy hillside with the dodo bird, the steam engine, and critical thinking.

More recently, VMP has been shining a light on underappreciated musicians like Usher, Alicia Keys, Dolly Parton, and Ludacris. You know, artists still working their way up through the ranks. Sleeping on hardwood floors, relying on the kindness of strangers, and subsisting on peanut butter sandwiches with RC Cola in a smelly van.

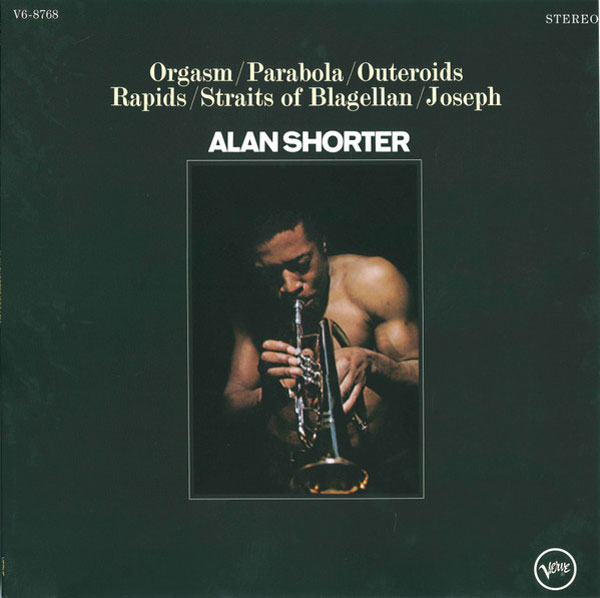

But every once in a while, they still uncover something special. I don’t know how long it would have taken me to find Dorothy Ashby or Gábor Szabó or Orchestra Baobab on my own. More than a few of the records that I’ve gotten from VMP over the course of the previous two years are amongst my favorites in my entire collection. And we can add their recent reissue of Alan Shorter’s Orgasm to that list. Immediately.

Honestly, I was hooked when I saw the album artwork. Alan, older brother to the more renowned Wayne, Shorter standing muscle-bound and shirtless, straining over a fluegelhorn and surrounded by late-60s style fonts with the Verve Records label in the lower right corner. It looks heavy and soulful with Shorter’s handwritten text on the back talking about how “the soloist must embark on what I call straight-line energies…” Sign me up.

Ryan K. Smith cut the lacquers on this one from the original analog tapes, according to the marketing. The transparency and clarity are immediately obvious from the first notes of the thirteen-minute album-opener, “Parabola.” Shorter’s fluegelhorn (cousin to the trumpet and popularized in the late ‘70s by the decidedly un-heavy Chuck Mangione) melds in melody with Leandro Barbieri’s tenor sax for a few bars before that melody dissolves and we slip into the Free Jazz stream. Barbieri is the first to blast off, and he gets all the way out there. Screeching and straining against Charles Haden’s bass – the only functioning compass on board by now. Shorter’s solos are generally less frantic than Barbieri’s. More cerebral, but still exploratory. Haden’s solo presents much more clearly in the mix than most acoustic bass solos of the era. It almost sounds like it was conceived on a piano with single notes and chords that resonate and decay before the players reconvene for another run through the opening theme.

Secrets Sponsor

While the structures of the songs vary throughout the rest of the runtime, the players’ personalities do not. Barbieri’s style is wild, exploding like spastic fireworks from strange angles. Shorter is more intentional and self-contained, liquid and meditative. When the trip gets expansive, the drummers (sometimes Muhammad Ali, sometimes his brother Rashied) go too so that timekeeping duties fall to either Haden or Reginald Johnson on bass. It’s a strange stew. Perhaps an acquired taste for some, but one that I took to right away. Like fermented tea or fried plantains. Dietary staples that others avoid like I dodge the news.

RTI pressed this one, and my copy is flawless. It is also a replacement for a defective copy that I received first. To be fair, the issue sounded more like the result of mishandling than a bad pressing. RTI often does great work, and they certainly did here. Regardless, I ordered Orgasm in late January and received a playable copy in early March, which is not an uncommon experience with VMP. But, barring catastrophe, I’ll be blissfully listening to Orgasm ten years hence, and I won’t be stewing about how long it took me to receive it. I’m excited to have found this lost sound. VMP hit a homer when they uncovered Alan Shorter’s orgasmic masterpiece.

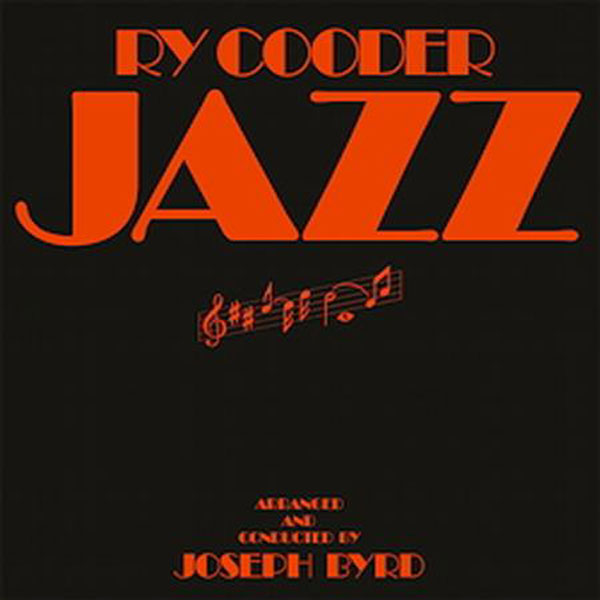

I like to imagine Ry Cooder living in the Sweet Spot that he’s created for himself over the course of the last sixty or so years. He’s generally considered to be one of the greatest guitarists ever, has hopefully earned enough money to live in comfort for the remainder of his years, but can likely still go to the post office without causing a riot. He’s played on some of my favorite recordings by the Rolling Stones and Little Feat from the early ‘70s, and he gifted the Buena Vista Social Club to the entire planet in 1997. I’ve cherished my copy of MoFi’s version of his Paradise and Lunch since 2017 and I’ve lamented not having procured a copy of Boomer’s Story (from the same series) since then. Perhaps his most meaningful contribution to the music that I love most occurred when he taught Keith Richards how to play in open-G tuning. If that did, in fact, happen as reported, Cooder would be well within his rights to stay miffed at how little press that has gotten, and at how seldom Richards has acknowledged it in print or on tape.

My affinity for reissues by Speakers Corners Records is much better documented. They’ve served as one of my most trusted sources for high-end vinyl for years now. But they’re not perfect. I got two bad copies of In Atlantic City by Wild Bill Davis and Johnny Hodges before I just gave up. And that wasn’t tied up with the industry-wide dip in quality we’ve seen recently either. They reissued that one in 2015, way before the world caught fire. But I’m excited to report that their take on Ry Cooder’s Jazz from 2019 is as righteous as one might reasonably expect. An all-analog production mastered by Kevin Gray and pressed (damn near perfectly) at Pallas. Man, I’ll take that action every time. You should too. Here’s why…

At this point, the 74-year-old Cooder seems as much like a professor or a historian or an archaeologist as a musician. Like a globetrotter excavating sounds to return home with. Sometimes, he places them in novel settings and allows them to brush up against disparate sounds from elsewhere. Sometimes, he brings them home intact and reveals the entire picture unmolested to the rest of us. Sometimes both. Jazz lands somewhere in the middle. He plays it pretty straight, but almost certainly with an expanded sonic palette.

Cooder’s essay in the liners tells us that he was mostly interested in exploring the songs and sounds of Jelly Roll Morton and Joseph Spence and Bix Beiderbecke when Jazz was conceived back in 1978. I don’t know for sure, but I’d be surprised if a harp was involved in Morton’s versions of “The Pearls” or “Tia Juana.” (Side note: what other rocker was playing a harp on record in the late ‘70s? Which ones are now?) But the initial flavor undoubtedly remains. The playing is straight. “The Dream” is an instrumental that finds Cooder playing bottleneck slide over Earl Hines’s piano playing, and I’d imagine that one still sticks out as a prime accomplishment for Cooder over the course of his stellar career. I mean, if Earl Hines was getting up off his throne to play with any other artists of that era, I’m not aware of it. He’s certainly not on any of my Stones or Little Feat records.

If you like Ragtime and Dixieland and New Orleans music and Old Time String Bands, but you’re challenged to find sonically pleasing original recordings from the early eras that saw those styles standing in the spotlight of popular consciousness, then the Speakers Corner version of Cooder’s Jazz might be the fix you’re hunting for. Gray’s mastering reveals the details that one hears in live performances of acoustic music: fingers against strings, bottlenecks against frets. The separation between instruments allows for a full appreciation of what the individual players bring to the party, and the playing itself is, of course, as skillful as any you’ll find from any era. This one is still readily available, but I’d grab a copy now in case that changes.

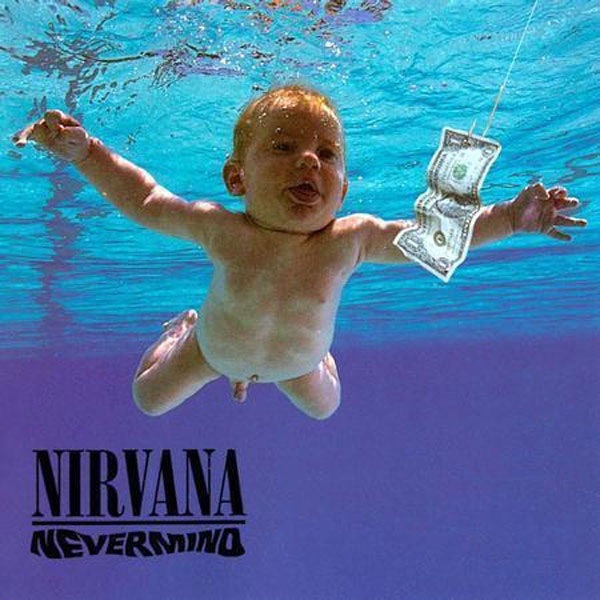

I was too cool for Nirvana when Nevermind hit. I’d already kicked my radio habit by then and was busy trying to transfer stamps from older friends’ hands to my own to get into live shows that I was too young to legally see. I was delivering pizzas for one of the Big Chains in Gainesville, Georgia (“the Poultry Capital Of the World”) when one of my co-workers told me that Kurt Cobain had died. The mood under the fluorescent kitchen lights was somber that day. The dipping sauces seemed curdled. The shredded cheese turned lumpy. The crust wouldn’t rise. But, other than the sadness inherent in a young person’s death, and despite my friend’s ashen appearance, I wasn’t really phased. Later, I’d be brought into the fold by Nirvana’s Unplugged record, and I’d work backwards from there. I spent a lot of money for a near-mint reissue of In Utero that was mastered by Bernie Grundman. Luckily, the David Geffen Co. recently “allowed” a repress of Grundman’s remastered Nevermind, and they’re selling it for less than $25. You should get one.

Despite what my nineteen your old ears dismissed out of hand, Nirvana was a legitimately great band. Cobain’s ear for melody and his musicianship might have been buried under his persona and a landslide of distorted feedback, but his talent was undeniable, in retrospect. I came around in time to cover “Lithium” in a band I was in at the turn of the century, and I’m proud to say that we freaked some kid out so badly that he ran from the bar clutching his hair, and encountered a friend of mine outside while babbling about the band inside “covering Kurt Cobain” before sprinting down Broad Street into the dark of night presumably in search of a Xanax bar and a hole to recline in.

Secrets Sponsor

And it’s cool to say that In Utero was the superior work, but I’m not so sure anymore. I hadn’t spent much time with Nevermind over the last twenty or so years until I picked up this recent reissue. The first side is like a roll call of inescapable heady rockers that land like an anvil, Cobain’s guitar solos mostly mimicking the melodies sung during the verses. Simplicity boiled down to its constituent parts so that only the bones remain but dressed up with modern production techniques that reportedly caused the band to question whether or not it had remained true enough to its Punk roots. “Territorial Pissings” might have something to say about that, thank you very much.

I saw The Batman last night, and it made liberal use of “Something In the Way” throughout its three-hour (!) runtime. The song itself plays towards the beginning, and I thought that the way it was absorbed into the film’s score after that was one of the coolest uses of music in cinema that I’d heard in some time. But I kept wondering what Cobain would have thought about his music being used in a tentpole Hollywood production. And I kept thinking about how unfortunate it is that my copy of Nevermind has a repeatable tick all throughout that song. Beyond that, my pressing is well above average, but some online commenters report having systemic issues across the board. I clean all of my albums with a Degritter, but it can’t clean up pressing defects. I guess I could just skip playing the last song, but then I’m not experiencing the work as intended. I mean, I didn’t skip the last scene in The Batman, right? It would be better to just go back to pressing good records. All the way through. Without the lazy mindset that “vinyl is an imperfect medium.” I have plenty of records that play well straight through, but not many of those were made after 2019. That defect is the something in the way of an otherwise stellar reissue. Hopefully, I just got unlucky and yours will be better. It’s worth the risk. If you don’t believe me, ask Batman.