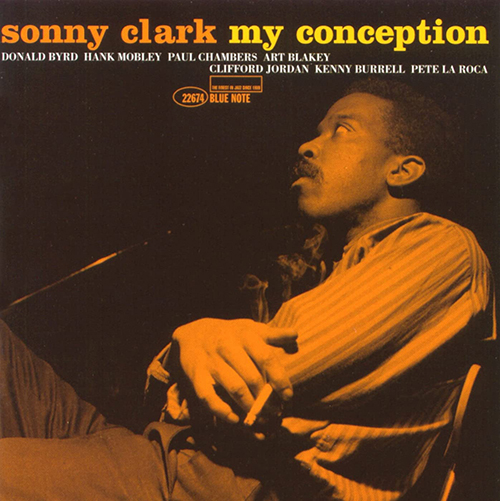

It’s been a while since I checked in on any of the Tone Poet titles from Blue Note. The series was inspired by a similar set from Music Matters Jazz, which was so impressive to the label’s president that he commissioned the same team to work up a scaled-back, more affordable version for the masses. The gatefold sleeves are less weighty, the expanded artwork less defined, but RTI was again entrusted with pressing the discs, and Kevin Gray still handles the all-analog mastering and lacquer cutting at his Cohearant facility. That’s a compelling dish for around $35 per title. When a friend asked my advice for a quick way to beef up her Jazz collection, I immediately thought of Tone Poet. When I saw that they’d just released a version of Sonny Clark’s My Conception, I advised her to jump based on the roster of players alone. Here’s why: Donald Byrd handles the trumpet, and Hank Mobley – perhaps my favorite saxophonist not named “Coltrane” – deals with the sax while Paul Chambers (bass) and Art Blakey (drums, clearly) lock down the rhythm. Clark takes care of the piano parts, but his primary contribution is as a songwriter on all six tracks. He seems content to wind his band up and turn them loose on his compositions. His playing is refined and understated but as essential to the proceedings as his more visible confederates. He did not live a long life, so his catalog is abbreviated. This might explain why My Conception was not released until 1979… 20 long years after it was recorded. The release was late, but the performances are on time. Conception would be a worthy addition to any Jazz collection, developing or established.

Secrets Sponsor

The opener, “Junka,” feels like you’re walking into your favorite team’s late-inning rally already in full swing, the band blasting out of the gate like a racehorse with its tail on fire. Mobley gets the first solo, and he makes solid contact, smacks one off the outfield wall. Donald Byrd steps up next and turns a double into a triple with sheer hustle and energy. Then, Clark. He’s content to let his teammates get the glory while playing a brief, tasteful solo serving more as dressing than the main course. Chambers gets a brief turn in the batter’s box, but his solo is further afield, off-mic and distant like so many other bass solos of the era. “Blues Blue,” as the title suggests, is a mid-tempo Blues workout with a theme so simple that one can imagine these masters using it as a warm-up for the more intricate material. That’s not to suggest in any way that it’s a throw-away number; it’s simply less fiery and more Earthbound than some of the more swinging tunes available here. It gives the album a more dynamic presentation by setting the stage for the speedier “Minor Meeting,” which serves as a showcase for Byrd’s hummingbird solos over Blakey’s moonshots and tidal waves behind the kit. By the time Mobley gets loose for one, you feel like you’ve been thrown onto the shore with your clothes tattered and the most delicious salt on your skin. “Royal Flush” starts side two with the ensemble joining in for a languid theme built around Mobley’s sax. His solo shows his ability to float like a butterfly, in addition to the more muscular playing for which he’s most renowned. “Some Clark Bars” gets things moving again with a quickened pulse and a particularly fiery fusillade from Blakey. As is his wont, Clark stays rooted and steady in the storm, brings a calm hand to the proceedings, and gives the listener time to catch their breath before Mobley and Byrd start throwing flames around Blakey’s beats. A couple of ensemble runs through the theme, and the comet vanishes from sight without a trace.

The title track, a gorgeous ballad, closes the program on a wistful note, with Mobley playing sympathetically and quietly over Clark’s sparse chords and Blakey’s muted high-hat taps. Online commenters complain about distortion during Byrd’s parts on this one, but I’m not hearing that. I’m hearing a pressing defect that takes the listener out of the game in the ninth inning with two outs and the bases loaded. Lasts for about 90 seconds. The pain is great. And it’s exactly the sort of issue that the Music Matters folks would not have abided by. That series is still the standard by which I judge all vinyl. But the Tone Poet titles are an above-average pinch hitter. This one’s a win despite the late-game error.

It seems like I’ve been a member at Vinyl Me, Please for five years, but it appears that I joined in April 2020. Since that time, I’ve ordered almost 70 records from them. As I’ve alluded to in previous missives, there have been frustrations. There was a substantial price increase that didn’t seem to do much for their quality control concerns. Pressing defects are still plentiful, especially with regards to titles pressed at G.Z. It would seem that their record mailers were designed as part of a kindergartner’s graduation project, which is an offense to kindergartners everywhere, I realize. If you receive a defective or damaged disc, VMP’s customer service representatives make it right. Every time. But they probably could have avoided the need for a price increase at all if they just did things right the first time. Right? Anyway, looking through my order history is a thrill on its own, as I’d be stoked to listen to any of the albums on the list right now. Or any time. The selections are great, and the quality ultimately is too. It’s just that the process for getting there is arduous at times.

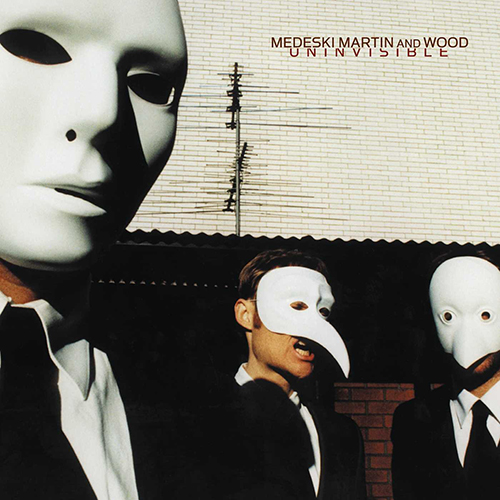

But every once in a while, they’ll release a title into the wild that seems preordained for greatness. When you get your ears on something like their recent reissue of Uninvisible by Medeski, Martin, and Wood, you’ll know what I mean. Like Cedric Burnside’s I Be Trying, Uninvisible was pressed at RTI, but it’s as clean as the linens at a five-star hotel right out of the wrapper. Are there tiers of quality within a single pressing plant? Can you pay more to get the best quality out of a facility? Or is it up to the artist to hold the plant accountable by rejecting a test pressing that’s not up to snuff?

Whatever had to happen to make Uninvisible fly, it happened on the first try. I mean, it’s pressed on transparent maroon vinyl with black “hi-melt” mixed in, whatever the hell that’s supposed to mean. Kinda hokey for a work of this weight, but whatever. Can you imagine what would have happened if they’d just pressed a couple of black discs?

Another riot at the capital, probably. Complete with tear gas, heart attacks, and obstructed inquiries. VMP pressed 1,000, and they’re long gone, but I included it in this month’s batch of reviews in order to give folks an idea of what can happen when VMP gets ahold of a good idea and then implements it according to plan. My copy is damn near perfect. As it should be. These people got fifty of my American dollars for a copy. And that was at the members’ rate.

As for the music: This one is a head nod masterpiece. You won’t want to be alone when you hear it. That would be as frustrating as seeing a UFO by yourself. Words will fail. Best to experience this one directly and shirk the need for translation entirely. It sounds like Justin Bua painting New York City. It’s fifty minutes of Soul-Jazz Organ Funk with a smorgasbord of instrumental textures. The title track kicks things off with blurry, Hip-Hop inflected trashcan drums, horn riff blasts, fuzzy keyboards, and smoothed out organ tones. “Your Name Is Snake Anthony” includes spoken words by Col. Bruce Hampton, who comes off like some sort of alien Ken Nordine while the band grooves in the background blending synth strings and electronic textures courtesy of DJ Olive. Medeski’s keyboard work during “Take Me Nowhere” sounds like light reflected on water. “Nocturnal Transmission” blends an ethereal groove like a cross between an organ trio and a Yves Tanguy painting mixed with a psychedelic soundtrack to a funky independent art film. “The Edge of Night” uses electronic beats that almost foreshadow the stuttering drum phenomenon that is trying so desperately to ruin what’s left of popular modern-day Hip-Hop. They work here in conjunction with gnarly organs soaked in echo along with Billy Martin’s kit. “Off the Table” pairs a downtempo lounge aesthetic with reverberating guitar notes and samples of what appears to be a recording from a ping-pong contest. Not kidding. That’s how the album ends.

If all that sounds like something you might dig, I’d recommend finding Uninvisible on the aftermarket ASAP. It’s a home run and will only get pricier with time. Such is the world of manufactured scarcity. If you’re not up for that, I don’t blame you. But I’d hold out hope and keep a good eye out for a potential repress from Blue Note. Maybe on standard black vinyl. If you can imagine such a thing.

I first saw Cedric Burnside perform in Atlanta during the 1996 Olympics. He was playing drums in his grandfather’s band when I arrived at Blind Willie’s after hauling ass from Al Green’s show at a massive converted old church across town. It was like finding a new religion. In fact, R.L. Burnside was the last artist to rearrange my mind and my orientation around what music could be and do. Now, Cedric has stepped onto the stage with something entirely new in his own right after seizing the spotlight with a powerful takeover through work that seems more like a Mission Statement than a standard album release. He’s been doing his own thing for some time now, but I Be Trying feels like an overthrow. A perfect blend of Funk, Soul, Rock ’n Roll, and (obviously) the Blues with a biting, percussive guitar attack that slashes and serenades, kicks, and kisses. He nods at the North Mississippi Hill Country tradition, but he’s not confined by it.

Cedric plays drums on most of the songs on I Be Trying, but at this point, he’s probably known more as a guitarist and vocalist. He plays guitar on every song here with neighbor and long-time collaborator Luther Dickinson helping out on a couple. Those two are rightly considered Hill Country royalty around the Memphis area. Hell, around the world by now. And, speaking of Memphis and royalty, Cedric sings “The World Can Be So Cold” into a mic that Willie Mitchell often used while recording Al Green. And Mitchell’s son, Boo, produced, engineered, and mixed the entirety of I Be Trying. Add Cedric’s daughter, Portrika, who sings harmonies on the title track, and you have a true family affair that could only have come from the fertile soil of that incomparable area. The talent there could rival any roster found in Nashville, Austin, New York, L.A., wherever.

Like all the best Blues music, these songs help you smile through the pain. High sounds illustrating low points of living. There’s a determination that’s both implicit in the grooves and lyrically explicit. The song titles reflect the theme. “The World Can Be So Cold,” “I Be Trying,” “Keep on Pushing,” and “Gotta Look Out” paint weary portraits of people struggling to stay afloat while navigating an increasingly challenging landscape on personal and societal levels.

Secrets Sponsor

On the other hand, the word “love” is in three of the song titles.

That’s where the hope comes in. There’s a wide range of human emotions expressed lovingly through words and music. Perhaps the greatest tradition we humans have developed, in this writer’s opinion.

Burnside achieves this level of storytelling mastery by employing various sounds and techniques that seem to have oozed into his being from the North Mississippi water that sustains life there. His vocals are refined but strong and emotionally arresting. His fingerpicking might be menacing or plaintive, depending on the song’s needs. “Step In” is made of juke joint grit. Dickinson’s slide helps with that, but it’s Burnside’s drumming that really locates you there as his high-hat snaps shut in a way that makes you clap your hands and kick your heels. The title track finds Burnside moving over to an electric guitar, giving the song a bit more grind in its gears. His daughter’s vocals add a layer of shine in conjunction with something that was on first listen difficult to place. A more focused consideration revealed a cello, plain as a sunny Mississippi day. “You Really Love Me” finds Burnside latching onto love to navigate through this perilous era with a spoonful of “Rollercoaster”-grade falsetto to force the medicine down. “Get Down” involves some tasty slide work designed to pack the dance floor, while “Love You Forever” finishes things off with a cool blast of water for those same undulating dancers after a night of sweaty fun and questionable decision-making.

This is my personal favorite combination of songs on the album, a perfect ending complete with a reprise of the cello’s role as support and foil for Burnside’s impressive falsetto. I Be Trying is currently sitting at pole position for my favorite collection of new songs in 2021. It was pressed at RTI, and unfortunately, they didn’t give Burnside their best work. There are some noisy parts, but the quality seems to have improved after multiple spins. Mine is quieter than it has been at any point since I bought. It would take more than a little surface noise to knock me off my love for I Be Trying, though. I encourage you to give it a listen and to support this great independent artist on his musical journey. Now’s the time.