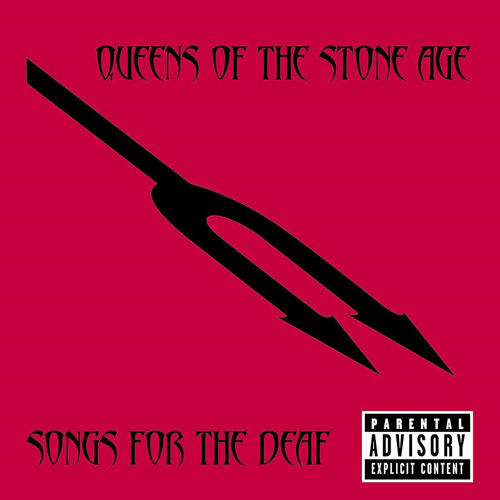

Not so long ago, in a galaxy far, far more similar to our current one than many of us can even recall, people went to see movies and listened to collections of recorded music, which were often called “albums.” There were many groups of unhinged people responsible for the generation of such art, and the Queens of the Stone Age was one such outfit. They released an album around the turn of this century called Songs for the Deaf.

Now.

Not only has this fabled album survived the larger and smaller ravages of our times, but it was recently excavated and restored to glory and pressed onto an ancient format called “vinyl” in a facility called “Pallas.” The Pallas People were able to generate two vinyl discs of strong quality with minimal imperfections before The Fire held sway.

The album’s gatefold reveals a car’s interior in grainy black and white. The dashboard stereo, even then, was of such a vintage as to involve dials, knobs, and a “cassette player.” No ubiquitous blue lights. Not even a digital display. This car’s interior and its stereo are dotted with QOTSA logos and song titles.

By dropping the needle on side one, we are dropped into a movie/album amalgam. We are clearly in the pictured car. The door dings to say it’s still open. Keys jingle as they find the ignition. The vehicle rumbles into sentience, and a radio station is barely coming in when the door shuts, and the dinging dies. The pilot fiddles with the dials until the signal is clear.

“You Think I Ain’t Worth a Dollar, But I Feel Like a Millionaire” breaks the horizon before bursting to the fore. And, just like that, we’re into the action. The scene is a cage match, and there’s blood on the fighters’ collective countenance.

Secrets Sponsor

Josh Homme directs and stars, both vocally and as the main guitarist throughout. He even writes scenes for others to sing. People like Mark Lanegan, for instance. Dave Grohl plays Homme’s sidekick and performs his own stunts on drums. And if Deaf were a heist film, bassist Nick Oliveri would be the wildcard member of Homme’s team. The one most likely to cause the job to fly off the rails. He probably makes the rest of the team nervous.

If “Millionaire” is the inciting incident, “No One Knows” is the “point of no return.” This is the scene that the album is most remembered for. Likely due to its crunchy syncopation, which builds to a furious bridge before dropping out to a bass riff that resolves again into a swirling, frothing cacophony.

There are allusions throughout Deaf to prior and future works. “God Is in The Radio” is like a Hunter S. Thompson-infused take on Norman Greenbaum’s “Spirit in the Sky.” “Song For The Deaf” nods to the band’s previous sonic movie, Rated R. “Mosquito Song” serves as the third act twist, delicately closing Deaf with languid horns and acoustic strings while foreshadowing the band’s next work by name.

Songs for the Deaf is a hand-held, shaky camera album with lots of quick cuts between images. It’s obvious that Homme and Grohl worked closely to get their scenes just so. It’s the sound of Too Much Fun come to life. It’s non-stop action with little room for subtleties. If you missed its first run, now would be an excellent time to familiarize yourself with the work. It’s a gem from an ancient time and a worthy representation of its genre. Don’t forget the popcorn.

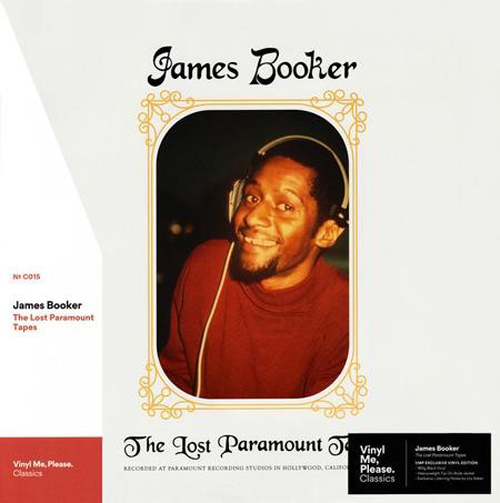

I recently learned that Dr. John played James Booker’s The Lost Paramount Tapes for his band members as an example of how he wanted them to execute his brand of New Orleans music onstage. So, I knew the musicianship was there. The only thing left to consider was whether or not to purchase the recent Vinyl Me, please reissue. You’d be forgiven for thinking this was a slam dunk based on my new report on their version of Al Green’s Call Me. But there were differences to consider. The Booker record was pressed at G.Z. as opposed to QRP, for instance. In my experience, G.Z.’s quality control is wildly inconsistent. The Lost Paramount Tapes is not a AAA production either. It was remastered, and VMP has not credited the responsible party. I hesitated, then I jumped anyway. And just like that time I hopped off the high dive into a fresh Florida spring as a small child, everything worked out swimmingly. The pressing is well above the pedestrian, if not flawless, and Booker’s band almost gets in the room with you. For those of you who skip to the novel’s end to mitigate suspense, the reissue is… delightful.

The session that spawned these sounds was recorded in Los Angeles one night in 1973. I know this because the “Listening Notes” told me. They come printed in Field Notes-style memo books, which are included with VMP Classics releases. (Classics are distinct from their Essentials titles and certainly from their Rap and Hip-Hop records. You can join any of the three separate clubs to have a record from your chosen collection shipped to you monthly.) Booker had skipped out on parole and headed to L.A. to circumvent an overly enthusiastic New Orleans DA. One night, he took his band straight to the studio from a club show. After being given his choice of a billion fancy pianos for the session, Booker chose a “tack” spinet, which provides the instrument with a Wild West Saloon vibe. No sustain, lots of notes, even more fun.

Secrets Sponsor

And Booker outright bends the thing to his every whim. I mean, he tools it, man. Fast and precise and fluid. The recording has a live feel to it, which is borne out by the knowledge that only Booker’s organ parts were overdubbed on “Feel So Bad” and “African Gumbo.” There’s a late sax solo on “Lah Tee Tah,” only arriving once the jambalaya is cooked, but the bulk of the album involves just bass, drums, and percussion in addition to Booker’s playing and singing. A guitar is buried in the mix somewhere, but no one cares.

Most of these songs are mid-tempo dance numbers. A viral pandemic is not the best venue for anything, and certainly not for exploring this record. You’ll wish you had friends around. Lost Paramount is a party on wax except for “Tico Tico,” which mostly serves as a workout for Booker’s hands. “Goodnight Irene” is a blast with its call and response vocals. “Junco Partner” is a personal New Orleans fave, and this version has a prominent walking bass and frisky hand drums. You can twirl to “Lah Tee Tah,” a safe instrumental. “African Gumbo” is for grinding, not smiling.

For the uninitiated, Lily Keber made a phenomenal documentary about Booker called Bayou Maharajah. She also wrote the notes for the VMP reissue. The doc’s almost as fun as the Paramount record, which is, indeed, essential.

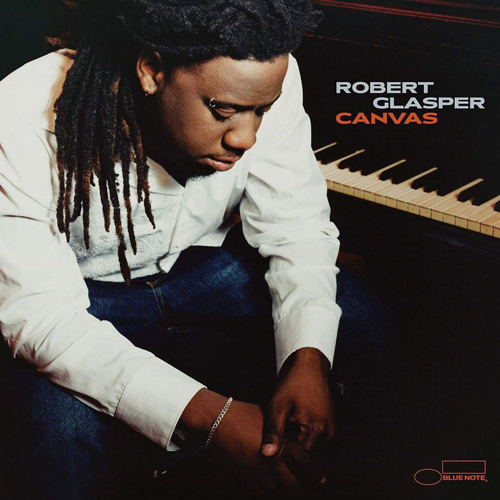

As a youth, pianist Robert Glasper performed publicly for the first time at the Texas Baptist church, where his mom served as musical director. Just last year, he unveiled the Baptist Gospel classic F*ck Yo Feelings. In between, he released his major-label debut for Blue Note in 2005. He called it Canvas. That one was recently reissued as part of the Blue Note 80 series, which is not to be confused with the more celebrated Blue Note Tone Poet program. The most apparent difference between the two campaigns is that the Tone Poet series is pressed at RTI, whereas Germany’s Optimal handles the BN80 discs. Kevin Gray turns the knobs for both. Tone Poet albums are all-analog all the time; BN80 releases are “all-analog whenever an analog source is available.” An assistant ProTools engineer is credited on Canvas, so we’re not in the AAA arena on this one. Let’s see…

Glasper utilizes a trio format for most songs on Canvas. Throughout, his piano sits right at the front of the stage with the drums in the back and the bass in between. The mix gives the busy drums a sort of “controlled burn” feeling. I’d imagine they sound more like a wildfire onstage. While the piano and bass occupy the middle of the soundstage, the drums are spread out across it with different components in different channels. The stage is not especially wide, but the players aren’t exactly rubbing up against each other either. (The occasional rubbing sounds are imperfections in the pressing. Minus one star.) There is very little depth or three-dimensionality. You’re not going to get pulled out to sea in any sonic riptides here. This is a polite recording, a safe space for you. And your feelings.

Canvas is composed of eight Glasper originals (plus one quick interlude), and a cover of Herbie Hancock’s “Riot.” Mark Turner adds sax to that one while Glasper works out on an echo-laden Fender Rhodes, giving the cover a more modern sound. “Portrait of An Angel” includes a bass solo that is much easier to discern than ones found on classic Blue Note recordings, during which bassists’ solos often sound distant and diaphanous. Damian Reid’s brush and cymbal work are reminiscent of the rainy day playing on Bill Evans’s Waltz for Debby recordings. When he suddenly lays out at the end of his “Angel” solo, Glasper is left in sharp relief. It’s an interesting way to funnel the listener’s attention, but the song never really develops or goes anywhere from there.

This is true of Canvas as a whole in a weird, contradictory sort of way. The playing is superb and a bit busy for background listening. I enjoy a more focused approach. Alone. I don’t want to worry about the work being “too modern” for my friends or whether or not someone is turned off by the lack of risk-taking. I saw Kurt Vonnegut diagram the plot for Hamlet once, and it culminated in a straight horizontal line across his whiteboard. Vonnegut acknowledged the work as the greatest story ever told, and he advocated against the emotional hills and valleys that typically make up a narrative. And a life. He’d have loved Canvas. It has a quiet confidence with Glasper’s notes weaving around and through the other players to create a sound that is more cerebral than sentimental. And you can’t be too smart at a time like this…

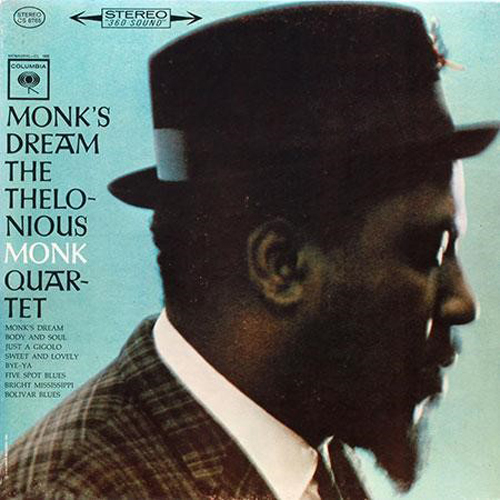

Columbia Records released Monk’s Dream by the Thelonious Monk Quartet in 1962. It comprised Monk’s first recordings in two years, but he didn’t exactly come roaring back with a brand-new bag. In fact, he didn’t even record new songs. He debuted one new composition and took a mulligan on seven others. It reminds me of stories I’ve heard about R.L. Burnside’s Mr. Wizard sessions. The producers asked him what he wanted to put down, and he simply suggested going over the songs they’d just released on his prior album. “Those sounded pretty good.” Anyway, everything that made Monk Monk is on shiny display in his Dream. That wheel didn’t need reinventing. It rolled over everything in its path and left canyons in its wake. There can be little doubt that he fashioned a serviceable trail for those who came next. The guy blazed even while working in retrospect.

Impex Records released their take on Monk’s Dream in 2012. It’s still readily available and is highly regarded in the audiophile community, for sound reasons. Kevin Gray’s mastering puts the players right in your listening room. The drums are hard left, the sax and bass sit squarely in the middle of the stage. Monk is on your right except during his solo numbers (“Body and Soul,” and an almost unrecognizable “Just a Gigolo”) when he assumes the central position.

The basic formula is even less novel than the repeat recordings. There’s often an introductory theme played by Monk, or Charlie Rouse (sax), or both. Then, one or the other takes a solo, and John Ore takes a long walk with his bass. His playing is especially tasty and ties the room together like The Dude’s piddled rug. He’s disciplined and precise so that Monk can take his freedom flights and still find his way back. Drummer Frankie Dunlop manages to play impossible accents and flourishes while sustaining the band’s pulse throughout.

Monk’s Dream feels less buttoned-down than Glasper’s Canvas. One could read a million books on Monk and come away with half as many takes on his personality and mannerisms, but playfulness and humor are undeniably prevalent aspects of his playing. Unpredictability too. Apparently, this was not always appreciated during Monk’s life, but history has shown him to be one of the top composers and most unique players of his time. His heavy left hand (Monk was once derisively referred to as “the elephant at the piano”) was perhaps too muscular for some tastes. Still, the precociousness of his right makes focused, attentive listening a joy. “Bolivar Blues” is a fine display. It finds Monk building melodies out of sustained, dense chords, then from flighty, single note runs with surprising angles and startling redirections. The sonic equivalent of a Steph Curry hesitation dribble.

MoFi released an “Ultradisc One-Step” version of this work recently, which is allegedly great but also backordered. Both versions (MoFi & Impex) were pressed at RTI, which I consider the industry standard, but my Impex pressing isn’t quite as clear as I’m accustomed to. There are off-mic vocalizations from Monk that some might find distracting. I do. Makes me feel like I have a fly buzzing around my face at times. Still, if you can come to Monk’s Dream with minimal expectations, you can safely assume that you’ll be rewarded with a flight of ideas and a new course of study. Monk’s Canyon still rewards repeated explorations.

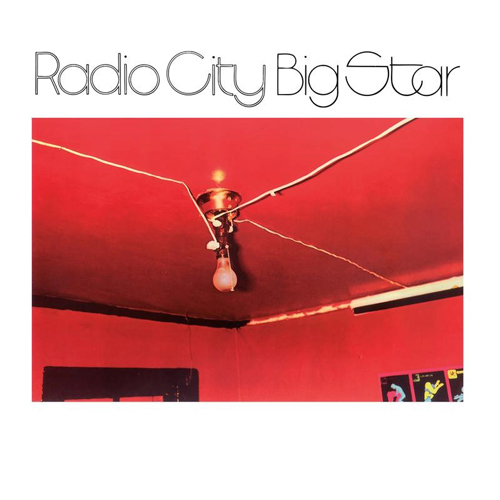

Us Big Star fans are a greedy lot. We’ve historically had precious little material to consume, so we focus like lasers on, and lord over, the three long-players available, while scanning the horizon continuously for signs of life dressed up like vault finds or fancy reissues. The previous few years have rewarded us with a slew of releases specific to the band’s third record, a serviceable documentary, some cool Chris Bell stuff, all-star live tributes, and whatever I might have missed while scanning something other than the horizon. For many of us, the gold is contained within the grooves of the band’s first two records. They’re undisputed classics. We’ve been over this before, but not recently. Craft Recordings has just put all-analog reissues of #1 Record and Radio City out into the world, and we’re better off for it. If you’re stuck inside, and you’re fortunate enough to have an operational turntable, it’s time to come aboard.

Audiophiles, as we all know, can’t agree on anything and will complain about an orgasm if we can find a willing audience. Or an unwilling one. I don’t participate in online audiophile forums, and I can barely even read them. They typically devolve into a bunch of people trying to out-snark each other while flaunting their superior taste and finely tuned ears. The Big Star catalog seems especially magnetic to this set. Not unlike the political climate in the country of this writer’s origin, listeners can’t seem to stop hurling their opinions at each other with the intent to injure, shame, or ridicule. But I came here to party, and that’s just what I’ll do. Y’all can argue about whatever you want…

I don’t have original pressings of either of Big Star’s first two albums. They’re hard to find, expensive, and reputed to sound overly bright due to an absent low end. And I actually believe that last bit is likely true. Neither my Classic Records version from 2009 nor Craft’s recent reissue is going to get in your chest and make you cough. But neither suffer from any acute tonal imbalances either. What is noticeable to my ears right away is that the Classic take pushes the hand claps in “O My Soul” right out to the front, whereas they are used as a texture in the Craft mix. (Chris Bellman mastered the Classic Records variant, Jeff Powell the Craft.) And we can extend that observation out to encompass any sound that behaves similar to those handclaps, anything that “pops.” So, the snare is a bit brighter on the Classic record, the sibilants are less sharp on the Craft reissue. On the whole, I’d say the Classic Records take is a bit brassier, and the Craft version somewhat more balanced and refined.

What I can’t quite figure out is how Craft can make their AAA reissues so affordable in comparison to similar projects by other labels. These records hover right around the $20 line. Vinyl freaks bitch about Memphis Record Pressing, same as everything else, but my copy is close to perfect. Between the two, I’d give my Craft copy the nod over my Classic copy for pressing. And maybe in general. I haven’t decided yet. I’m not ready to part with either until I do. We can split hairs until we’re bald, but I think the important thing is that we have access to two essential Big Star classics in AAA form on quiet vinyl with tasteful mastering for the foreseeable future. It’s hard to complain about that.