I like to play a game wherein I imagine that my favorite singers discovered their voices fully formed on the first try without practice. Like, imagine Axl Rose’s surprise when he first opened his mouth to sing, and the scream that starts the guitar solo in “Welcome To The Jungle” fell out. Big eyes, hand over mouth, but then that sound escapes again whenever he moves his lips…

Now, try it with Robert Plant. Or Merry Clayton.

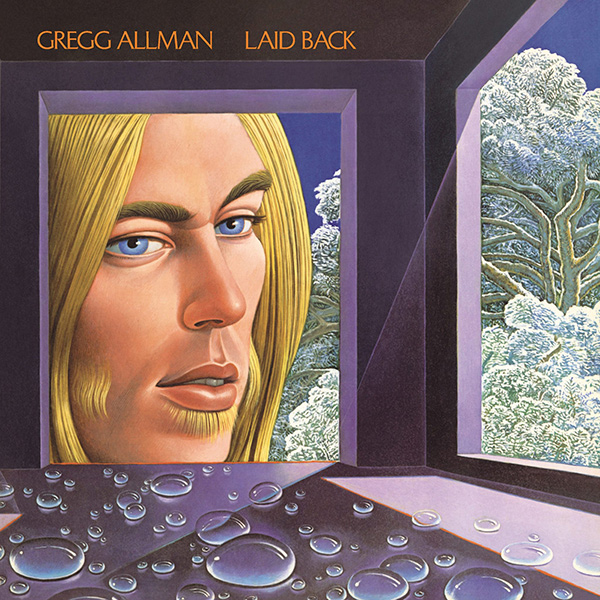

All those singers really turn my tater, but the most fully-formed badass pop singer that I know of at a remarkably early age was Gregg Allman. I know he wasn’t born that way. I know it took work to get there because there are enough extant early recordings to trace his development. But I also know that he was only 21 when the Allman Brothers recorded their debut album and that he had already achieved the gravelly greatness that would be his calling card for the rest of his, and his band’s, life. I knew it the first time I played my dad’s copy of Eat A Peach. It didn’t look or sound like anything else in his collection, and how could it? I think of the Allman Brothers Band as being amongst the most original of all American bands, and I consider them to be a national treasure.

Secrets Sponsor

Luckily for me, Mobile Fidelity undertook an Allmans reissue campaign a few years back that covered their most essential recordings. I supplemented that with a sealed copy of their Dreams box set and considered myself done with Allman Brothers collecting. And, technically, I was.

But what about solo efforts?

Analogue Productions reissued Gregg’s solo debut, Laid Back, in 2015 and I… missed it. Had to stalk it online for years until, one glorious day in 2022, I got an email advertising a repress. I didn’t miss this time.

I jumped all over it and thank goodness for that. Laid Back walks a tricky tightrope that deftly spans and skirts some of my favorite and least favorite Rock ’n’ Roll tropes. But somehow the parts add up to a cohesive whole that pulls me in every time. Gregg’s voice would do that on its own, even without his big brother’s interplanetary slide guitar expertise to bolster it. That’s not especially remarkable at this point. But I can’t believe how well the symphonic arrangements work. Even at their most overblown (during “All My Friends,” for example), I don’t go screaming for the exits. I just let them wash over me while I drift away on that man’s singing. By the time he starts “Will the Circle Be Unbroken” with only sparse piano accompaniment, I’m hooked and it’s time to start the record over again.

Because that’s where you’ll find the reworked “Midnight Rider” with its lazy, smartass slide work standing in such stark contrast to the more menacing version by the Brothers Band that we’ve known all these years. It’s followed shortly by a bedazzled take on “Please Call Home,” that comes a little closer to the Band’s original, but with the sharp corners rounded off and padded. A bit more Gospel, a little less Devil. The choir helps with that.

And Ryan Smith’s mastering helps you hear the details. The highs float off into the humid southern swelter, the lows crawling around just beneath the red clay, both distinct as the south’s various barbecue sauces. (I like vinegar-based, don’t like putting ketchup on pork…) QRP’s (re-)pressing is one of the cleanest I’ve encountered during the Age of COVID-related Quality Control Conundrums. Laid Back is still in stock so I don’t guess everyone was hawking it like I was, but I’d get one now just to be safe. You won’t want to wait another seven unlucky years for a repress. Trust me on this one.

I certainly didn’t find any Makaya McCraven records in my dad’s collection. That would have been a hell of a trick though. McCraven is younger than I am by nine years. I first heard of him while reading liner notes for a Charlie Parker box set. I picked up a copy of his Universal Beings record and have struggled to listen to much else since. This guy’s working on another planet. A level that we can’t see with the human eye. I tried. I finally caught one of his live shows at the end of February, but…

…it was not what I’d heard on record. I sensed that going in, just based on the fact that dude’s creative process results in records that would be nearly impossible to recreate in a live setting. He essentially records all of his shows, with varying bands and lineups, then chops the tapes up and loops them and layers them until he’s created an entirely new sound. A Jazz performance with Hip-Hop production. As I understand it.

But when he plays live, he’s just another Jazz drummer leading a band of improvisers through various scenes, terrains, and situations. That’s not really true. He’s, quite literally, one of the most accomplished keepers of time that I’ve seen. Or heard of. I stood behind him for much of the show, and it almost seemed like he was an android. His movements were so precise and repeatable. His wrists seemed to be locked into some sort of pattern that resulted in a perfectly balanced attack on his kit. He did mix some electronic sounds in there, but for the most part, he did it the old-fashioned way. He earned it.

I guess I should mention at this point that he was touring in support of his latest release, Deciphering the Message. It’s not like Universal Beings or In the Moment, both of which make use of the techniques described above. Deciphering the Message was constructed from samples of old Blue Note recordings, then augmented by new sounds that McCraven and his band – many of the same players that I saw on stage in Oakland – made.

The first thing I noticed while listening to Message was that the recordings were less clear than what I’m accustomed to. Because most of my classic Blue Note titles are from the Music Matters Jazz reissue campaign. Everyone is probably tired of hearing me talk about how they’re the finest sounding records in my collection, so I’ll leave that out of this review.

The second thing I noticed while listening to Message was that I immediately wanted to hear it again. It’s a lot of fun to listen along and try to identify the songs I’m hearing without consulting the liner notes. But I suck at that game because I never know the names of songs that I like. Especially the ones without lyrics. So, it’s a good thing I have those liner notes. They detail the original source material (song name and original album title), the original players and their chosen instruments, as well as the new players and theirs.

I recognized Kenny Dorham’s “Sunset” (from Whistle Stop) right away but couldn’t place it. I did not pick up on Art Blakey’s “When Your Lover Has Gone” (from A Night In Tunisia), but I love that I can pull that record off my shelf and compare the two versions in an (often vain) attempt to decipher McCraven’s contributions. It’s a game I could play all day every day if I didn’t have to work.

I think this album will appeal to almost anyone willing to loosen their Jazz collar and give it a fair shake. It’s not the most sonically spectacular recording you’ll hear this year, but it might be one of the most interesting. The samples, almost by definition, seem to be a couple of generations past their sonic primes, but they’re as emotionally invigorating today as they ever were. Pressing is good. If you’re a Blue Note fan, and you skew towards intrepid, push your expectations aside and give Deciphering the Message a focused listen. It’ll reward you.

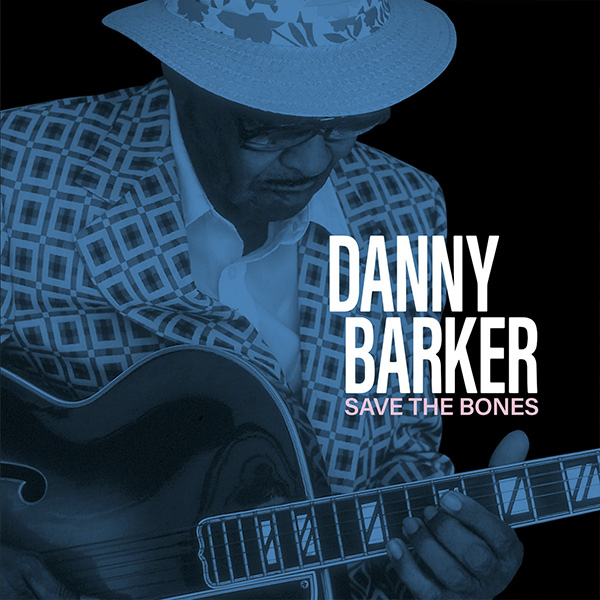

I have some of the most thoughtful friends in the world. I’m grateful for everyone who has tolerated me for these 47 zesty years. One of my besties gifted me a subscription to the Tipitina’s Record Club last Christmas, and I’m still reaping the rewards. The first record I received from the club was by the Dirty Dozen Brass Band with Dizzy Gillespie sitting in. It’s a ton of fun, as you can likely imagine. But I wasn’t quite ready for the feel-good record of the year. The millennium, maybe. I mean, I guess I’m cheating a little because Save the Bones by Danny Barker is not actually from this year. Or this century. It’s from 1988, but it could have been from 1920 or from 2220. It’s a man’s voice and his guitar recorded simply and without artifice. It’s fashionable to fawn over the ‘80s and to fetishize the plasticity and the pastels that were so ubiquitous in that era, but – really – that decade sucked. For fashion, for (American) politics, for music, movies, and literature. There are stellar representations from each category, obviously. Except for fashion. The ‘80s gave us Appetite and Do the Right Thing. And White Noise. There’s good stuff there, you just have to dig. Like always, I suppose, but somehow the ‘80s feel like a cultural nadir.

But not when you’re listening to Save the Bones.

Secrets Sponsor

Save the Bones is a celebration. Like New Orleans music is a celebration. Or like New Orleans itself is. The liners will tell you that Barker was 79 when he recorded Save the Bones. They’ll tell you that he played on over 1,000 recordings before making his first solo album. This one. He played with Cab Calloway and can remember seeing Joe Oliver live and in person. He was a Jazz historian and was instrumental in the formation of the aforementioned Dirty Dozen Brass Band, and he gave Wynton and Branford Marsalis a leg up early in their careers.

He was also hilarious. The title track on this album would be the best song to wake up to every morning for the rest of our collective lives. It’s about Henry. He doesn’t eat no meat. Because he’s a vegetarian. Barker’s delivery is conversant. His playing fluid, but not flashy. He’s clearly playing chords that I don’t know, but they don’t sound like the convoluted finger breakers that the flashier Jazzers often employ. They sound like something a human could achieve with some practice. And this might be recency bias, but I think Barker’s take on “Saint James Infirmary” is my favorite. His or Son House’s. Barker’s is more melodic and almost lilting at times. Son House always sounded like a knife between your ribs, and there’s plenty of room for that in this world, but maybe not right now.

Right now, we could use some uplifting. Albums like Save the Bones or Errol Garner’s Magician might do the trick. Somehow, I’ve linked the two in the senses of my memory. The one described above is a stripped-down affair with vocals, spoken asides, and tasty strumming. The other, described here, is a joyous piano workout complete with off-mic grunting and neologisms to spare. They couldn’t be more different in presentation, but they both make me smile. Even me. If I knew where to look, I’d seek out titles that produce a similar effect, and I’d give them their own section on my shelf. Or I could just set aside a New Orleans section and supplement it with Magician.

The records I’ve gotten from Tip’s Record Club are almost certainly not AAA productions, and the pressings are just above average. But the overall effect is far more impactful than that description suggests. If you’re looking for some good, dirty fun, I’d consider a subscription. Right away.