Alright. This is going to take a second so let’s get right to it…

Wilco released Yankee Hotel Foxtrot on April 23, 2002. Officially. I remember it being the first album that I heard online in advance of its release date as there had been a squabble with the record company, and the band opted to do things a little differently with regards to making the work accessible. You might have seen the movie.

Secrets Sponsor

Anyway, as is so often the case these days, a deluxe edition was released this month in honor of Foxtrot’s 20th anniversary. But we’re not here to piddle with that. No, we are not. We’re going to get to the bottom of the “Super Deluxe Edition,” by golly. We’re going all the way. Eleven (!!!) 140-gram records on black vinyl. Two were devoted to a remaster of the original release, six tied up in “outtakes, alternates, demos, drafts and instrumentals,” and three documenting a live show from the Pageant in St. Louis on July 23, 2002. (There’s also a really cool book. And a CD. Something about a radio interview and live performances from 2001, but I’ve not heard it yet.)

Wilco: “That’ll show them…”

It goes like this: there are multiple “albums” within the larger set. In addition to the remaster, there are three distinct sets with Building Yankee Hotel Foxtrot tagged onto the ends of their titles. My concrete mind wants to be able to break these albums up into categories. One should be the rocking version of YHF, another should be the weird one, and on and on like this. What’s more, the first set should be more sparse, and subsequent versions more layered and complex until we arrive at the watershed moment that we remember from the dawn of this century.

But that’s not how it works. Like the original, the expanded set is unpredictable, filled with sonic switchbacks and ambushes. The buildings (songs) in the City of Foxtrot are deconstructed as often as they are enhanced. American Aquarium contains my favorite discovery in the set, a Bubble Pop gem called “Shakin’ Sugar” that would later crop up on a Jay Bennett solo release. Here Comes Everybody finds Jeff Tweed screaming “Not For the Season (Laminated Cat)” from a sandpaper windpipe while The Unified Theory of Everything has the crunchiest version of “Kamera” available. And there are plenty to choose from because some version of that tune is included on every album in the set.

Lonely In the Deep End – Demos, Drafts, Instrumentals, Etc. was what drew me in initially, and it didn’t disappoint once it got rolling. Seems that the earlier demos In the Deep End are only tangentially related to the finished version of the album. They also sound like they were recorded through a telephone. They’re sketches. Things warm up a bit as the demo’s progress, both sonically and performance-wise, breakdowns included. The abandoned run through “Jesus, Etc.,” one of my favorite Wilco compositions, is especially informative. And funny.

The St. Louis show is so clearly recorded that it sounds like an in-studio live performance at times. It includes material from all of the band’s four releases up to that point, and it’s a cool snapshot of where the band was onstage at that time. I also have live sets from the Being There and Summerteeth tours, which means that I have three professional-grade live documents from my favorite era of one of my favorite bands. So… I think I have a cool Wilco collection. If you think yours might be even cooler, I’d love to hear about it.

Secrets Sponsor

Almost all of these “deep dive” sets seem bloated and unnecessary to me, and I keep thinking that I don’t have room for this one on my shelf, but I’d have a hard time parting with it at this point. It sounds great. The records were mastered by Bob Ludwig and cut by Chris Bellman before being pressed at Optimal. Everyone did a fine job in their respective roles. There are lots of weird details that come through loud (or quiet) and clear here. Thumbs thumping strings so that they slap against the fretboard. Tweedy’s vocal fry decaying into the surrounding sound effects that caused those Warner Bros. executives so much anxiety at the day spa. All but one of my records are flat and perfect excepting a brief instance of non-fill at the outset of the sixth disc which causes a tick that repeats twice. It’s almost not worth mentioning except that it sounds so jarring in comparison to the rest of the set’s flawlessness.

Here’s something to know: A direct comparison of my original pressing to the remastered version of YHF reveals airier highs on the reissue, more brightness, and a bit more tin in the sound. The original feels more solid and formidable to me, with a more rounded top end. Like a luxury vacation for your ears, it imparts no listener’s fatigue at all. I prefer it while my listening partner appreciated what she experienced as increased clarity on the reissue. To each their own. I don’t think you can lose here.

Knowing how long the band worked on this set of songs and having learned how great most of the alternate versions of the songs were, I think the most impressive feat that the band achieved was actually settling on a final version that bests the others. I’ve spent entire literal days listening to this set, and I’ve never tired of the material. But the original is still the most fulfilling listen. It’s one of my favorite releases of the past 25 years. And that would be the case even if I didn’t know that the record label fought the band at every step of the process. (From the included book: “Every time you send it to us… it’s worse!”) Or that the label paid for the album twice. The story will never get old, but the music somehow seems to get younger as the years pass.

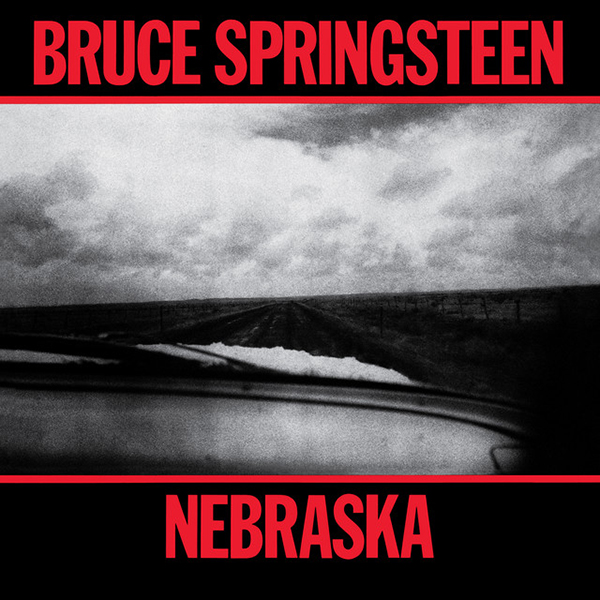

I don’t know this as a fact, but I’d imagine that Springsteen’s Nebraska was at least as confusing to the general public as Wilco’s Yankee Hotel Foxtrot was to their record label upon release. It’s easy to hear Nebraska with the right ears in today’s Post-Unplugged era of acoustic appreciation and onstage music stand acceptance. (I’m not bothered by watching someone read lyrics off of a sheet on a stand, but I’m mortally offended by watching folks read off of an iPhone onstage. That’s unlikely to change. I’m stuck with it. Also… get off my lawn!) In fact, it was probably inevitable as a response to the Plastic ‘80s and their Overblown Everything.

But Nebraska, at the onset of that debacle of a decade, might have sounded alien to Rust Belt Americans who had accustomed themselves to inner tubing down The River just two years prior. You’ll find plenty of hungry hearts in the Nebraska characters as described, but you’ll play hell finding anything like “Hungry Heart” in Nebraska. Don’t bother.

To many, Nebraska would have seemed like the very definition of a departure, but not to Springsteen himself. He had, after all, patterned at least part of his earlier songwriting on those of the ‘60s Folk progenitors. Enough so that his label initially marketed him as an updated take on Dylan. (There’s some hilarious footage somewhere of Clive Davis earnestly reading lyrics from “Blinded By the Light” directly into a camera as a promotional spot for Greetings From Asbury Park, but I can’t find it online. Which is relentlessly unfortunate.) Dylan wrote and recorded these songs in his home on a four-track with sparse instrumentation and arrangements. He intended to use the demos as the framework for songs to work up further in the studio with the E Street Band, but they weren’t coming across, and he eventually settled on releasing the work as it was: essentially haunting.

Essential and haunting.

Such that Vinyl Me, Please reissued Nebraska as their Essentials Record of the Month in October. This is not a AAA release as the album was subject to Plangent processing, a digital technique employed to adjust for wow and flutter (slow and fast pitch fluctuation as a result of irregular tape movement). I’m not bothered by this in the least. VMP successfully used the same process on their Erroll Garner release, which was only compromised by a subpar pressing – the mastering is phenomenal. A pattern that would sadly repeat, though to a lesser degree, with this Springsteen reissue and others.

The VMP pressing, by GZ who also pressed Springsteen’s reissue campaign from 2018, is way more listenable than the Tom Joad record described in the article linked above. But there’s some noise, specifically during “Highway Patrolman.” This is objectively sad, but not insurmountable. The issue lasts for approximately 20 seconds and it’s the only pressing problem resulting in repeatable ticks. Seems like this type of nuisance often presents at the very end of a side, and that is the case here. Maybe we can blame it on the damned “black smoke” colored vinyl, but probably not. The Joad record was pressed on standard “grown adult black” vinyl, and was demonstrably crappier than this version of Nebraska so… who knows?

Barry Grint’s mastering is another story altogether. It allows Springsteen to tell the clearest version of this harrowing story yet. The VMP cut is noticeably louder than my original, so I’m predisposed to thinking that it automatically sounds “better.” But even accounting for that, the remaster results in a remarkable increase in clarity and detail. (The same could be said for the enhanced album artwork, I might add.) Notes that I never noticed present like guests that you never expected to see at this 40th-anniversary reunion. The distorted vocals are still present in places, but those are almost certainly baked into the original master. Perhaps as a result of having been taken from a cassette in the first place. It just adds to the grit, the dusty boots, and the greasy jeans that make Nebraska what it is and what it’s been all this time.

If you don’t know what that is, you should. Nebraska is as cinematic as anything in Springsteen’s canon, but this is an independent film shot in grainy black and white. It’s about drifters, murderers, cops, and folks trying to claw their way up out of the American mud. You’ve met them before, but you might not have seen them this naked. VMP’s reissue is the 4K Criterion version that reveals the pores in the characters’ struggling faces. It can’t always be roses. Sometimes, you’ve gotta get the thorns. Nebraska is the whiskey that helps that bitter medicine go down.

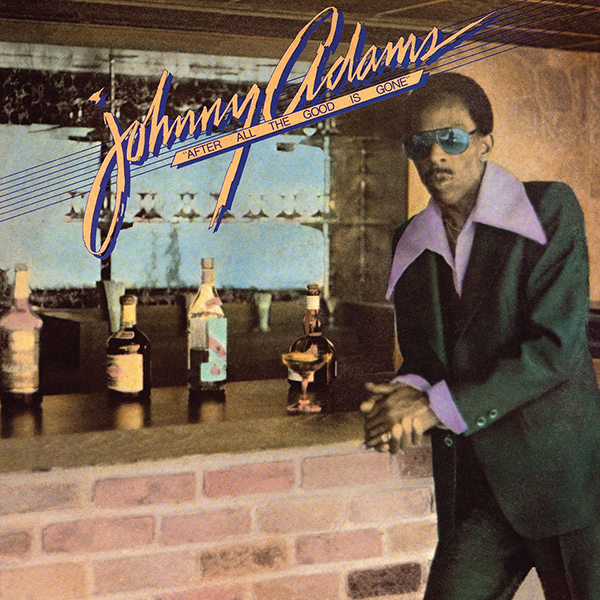

One of the most thoughtful people I know gifted me a subscription to Tipitina’s Record Club for Christmas last year. Somehow, I was unaware of the service prior to receiving my first of their releases, Live in New Orleans by the Dirty Dozen Brass Band with Dizzy Gillespie. That one’s a hoot, but Danny Barker’s Save the Bones is the Tip’s release that has had me buzzing for the last few months. I’ve worn it out. I’ve also gotten stuff by Trombone Shorty and Etta James, both of which are fun, but not essential. The Shorty record because the content is a little weak, and the James record because of the recording quality. All of the releases have sounded distinctly New Orleans, whether they observed that city’s musical traditions overtly or less obviously. After All the Good Is Gone, by Johnny Adams, falls into the “less obvious” category.

The title track was a hit for Conway Twitty in the ‘70s and is one of two of the Country crooner’s tunes that Adams covers on All the Good. None of the songs really scream “New Orleans!!,” including the two Funk-ish workouts that close each side. The first, “Chasing Rainbows” sounds familiar to me, but I can’t place it and an online search didn’t turn up anything that I recognized. Adams’s take on Bernstein and Sondheim’s “Somewhere” from Westside Story is immediately identifiable and sounds suspiciously thin in comparison to the other material included on this set. “She’s Only a Baby Herself” is another head-scratcher, and appears to be a cover of a Smokey Robinson song that the Motown legend released in 1974. It’s hilarious, and I have to imagine that this was not the intended effect.

Much of the material on All the Good seems dated, up to and including the packaging. (I mean, get a load of that collar.) Some of Adams’s vocal techniques further the consequences. They may have seemed compelling in a sweaty Ninth Ward club circa 1978, but in 2022 they seem a little overwrought, sometimes borderline histrionic. The guy has range, no doubt, and I’d have been curious to hear what he could have done with the Meters backing him up. Or something. The liners state that no less than Cosimo Matassa “cited Johnny as the greatest singer he had ever known.” This seems ludicrous if one knows that Matassa recorded some of Little Richard’s most rocking records, but everyone gets an opinion, and Matassa actually earned his. So…

Maybe it’s the string section or the electric sitar? Maybe it’s the Nashville Country influence? The whole thing sounds a little too light to me, a little “local.” Maybe it’ll grow on me with time. It already has a bit, I guess. But I’m more looking forward to the forthcoming Fats Domino release shipping soon. Or the Christmas album coming in December. Tip’s can’t compete with VMP’s mastering team. Or if they can, they aren’t. I suspect there’s a distinct gap in funding and finances. The Tip’s club is fun though. The included keychain reproducing the After All the Good Is Gone artwork was almost worth keeping for the kitsch factor alone. Almost. If you’re looking for a compelling smaller business’s endeavor to support in the World of Vinyl, Tipitina’s Record Club would be a fine one to get behind. After All the Good Is Gone might not be my favorite album, but I’m happy to have heard it. And I wouldn’t have without Tip’s club or my thoughtful friends.

I’m thankful for it all. Maybe you would be too…