For over 50 years, pianist Menahem Pressler’s name has been indelibly associated with the Beaux Arts Trio. As the founder of the trio, it is Pressler’s pianism that is the constant in the trio’s over 50 benchmark recordings of Schubert, Brahms, Beethoven, and other great composers.

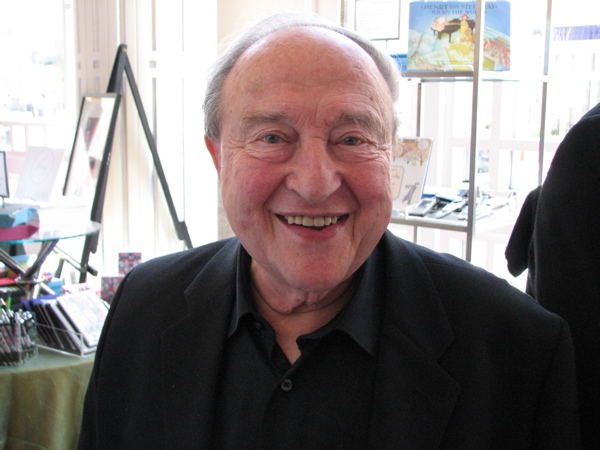

Although he retired the trio last season, Pressler continues to perform with chamber ensembles worldwide, as well as present solo recitals. He also frequently teaches master classes worldwide (including this summer at Music at Menlo in Palo Alto, CA), and works with students as Distinguished Professor at Indiana University. The latest book about his work, William Brown’s Menahem Pressler: Artistry in Piano Teaching, was recently published by Indiana University Press.

Pressler fled from the Nazis in 1938, leaving his hometown of Magdeburg, Germany for Israel. In 1946, he launched his international career after winning the Debussy International Piano Competition in San Francisco. To begin to detail the octogenarian’s many accomplishments would take another book.

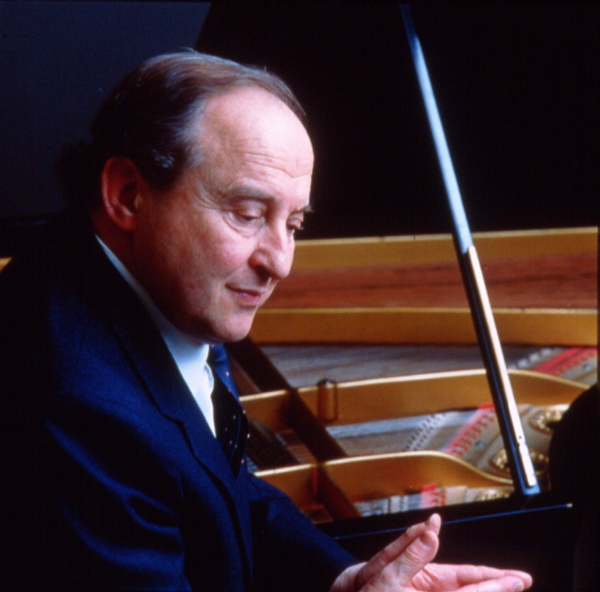

Less than a decade ago, when I first heard Pressler perform live with the Beaux Arts Trio, I was astonished at how closely his sound resembled what the microphones captured on the trio’s many recordings. Pressler’s sound is like a miraculously soft cushion that cradles his partners’ instruments as they figuratively move around and through the piano’s strings; its airiness is not something conjured up by Philips’ engineers. There’s nothing else quite like it. The man’s touch is magical.

Pressler and I met up in Fort Worth, TX on June 5. He was once again judging the Van Cliburn International Piano Competition, which I was covering for the U.S. edition of Gramophone magazine. When we sat down in a very noisy lobby to chat, we began by discussing competitions and their importance. From there, we briefly touched on one of his forthcoming recitals in Northampton, Massachusetts, then launched into an animated back-and-forth on classical music in modern times. It was a joy to spend time with such a great artist.

Jason Victor Serinus: You’ve judged the Queen Elizabeth Competition five times, the Cliburn five times, and will do Leeds for the first time in May.

Menahem Pressler: I’ve also done Santander in Spain – all the great ones. These are the big competitions with the biggest prizes. There is a very big prize because we try to find the young players – it means something.

There are now hundreds of competitions around, but you need really to win a competition like the Cliburn, which gives you over 100 concerts, and three years of management. It’s the dream of a young pianist.

JVS: And a recording.

MP: Yes, and a recording. Recordings are still very important, but you must find a new niche somewhere or on the internet.

JVS: It’s so exciting that you can download CD quality and high-resolution files that are superior to CD-quality. It’s a whole new world.

What is different about this competition and the atmosphere?

MP: To begin with, nothing is actually different from certain points. Every competition looks for the best young players. But the differences are, first, the amount of prizes. The prize here is tremendous. It was the first competition to give such a big prize, although Brussels preceded Cliburn, and Brussels discovered Gilels, David Oistrakh, and Fleisher – very many wonderful people came from that competition, in a sense maybe more than here. But here was Radu Lupu. But when he won the First Prize, he didn’t accept it really. He went back to school in Moscow, went to Leeds. When he won the First Prize in Leeds, he started his career. So a competition is very important.

We went around the world auditioning players, and selected from over 150, 30 to come to Fort Worth. They were in Russia, New York, China, all over the place.

When you select them, you select players that would make a competition important.

JVS: What does “important†mean?

MP: The caliber of the player. A competition is only important for two things: the caliber of the competitors, and the caliber of their jury. Not many competitions can now attract a great jury. Very often you find on a jury bench teachers who have never experienced what it is to be at 8:30 on a stage. To get a fine judge, he must have been a teacher and, at one time or another, an active performer who understands what it takes to be onstage. It’s completely different than when you are in four walls that are safe.

What makes a performance great is not just that they play well the instrument – that’s taken for granted – not just that they do know styles – not just that they are experienced onstage… What we are looking for are the replacements for the great ones that are leaving. Inspiration and artistry, which is the peak of the pyramid – technical, musical, the artistic inspiration – that’s what we are looking for.

Of the six finalists, we have a Chinese, two Japanese, a Korean, a Bulgarian, and an Italian. Everyone has some insight that they’re bringing to their training, their outlook. You know, I firmly believe that where you were born has an impact on your outlook. Yet, we are all concerned with the same kind of music. The Chinese plays Beethoven and Mozart, the Japanese Chopin and Beethoven, the Bulgarian plays Chopin and Schubert, the Korean plays Chopin and Schubert and Godowsky. They are all vying for a prize with something that is our cultural heritage. This makes our life more beautiful.

JVS: I couldn’t watch much of the competition before I arrived because I was consumed with deadlines.

MP: You can still watch now. You can recall all the performances.

JVS: I know. But I have to go back home to my newer computer.

I heard a wonderful interview with you with Jade Simmons. You repeated some of those things onstage at the judges’ panel, as did another judge. You both emphasized the spiritual qualities of the music, and touching the heart.

On the other judging panels, you’ve been, do the other judges feel the same way?

MP: How can I answer for them? I cannot answer for them. But I can say, generally speaking, because we don’t talk about those things. It is actually discouraged that the judges speak – we just vote – you can speak, but we can’t go into details, etc. – we vote for our preference, the votes are counted, and the winner is declared.

I find that 99%, we voted for the same things. Now, those are my values. I don’t know. I would presume their values are the same, because when we hear someone playing well, and he plays spiritually well, you will hear a special quietness. You will hear that the audience listens. You hear less coughing. It is like when somebody wants to hear a speaker say the right things. You don’t dare to breathe actually so you can hear the speaker. The same is true here.

JVS: I felt that way with the woman who was playing. I’m not going to ask you about her…

MP: I’m not going to answer…

JVS: Of course. And I’m not going to look at you to see your reaction.

I don’t get a chance to see. Do you have score sheets?

MP: We have score sheets with every name, and we know the numbers. We have a number system, and the number system gets reduced. When we have 12, we had a different number system than when we had the 30 [Note: One contestant withdrew before the competition began, leaving 29 pianists at the preliminaries]. I presume it will be a different number system when we have the six.

JVS: So you don’t have different categories, and rate technicalities…

MP: No. You do that inside of you. The jury doesn’t want to know that, or the others don’t.

JVS: Yes. I judge a whistling contest where people say we have to grade things by degree of difficulty.

MP: Yes. But the whistling of course is not on the level of these pianists. The repertoire is not on the same level.

JVS: Yes. And not only that, but often people are technically accurate but boring as hell.

What are you playing in Northampton, MA at Music in Deerfield on October 30?

MP: I can’t remember. Is that with the American Quartet? I have to look that up.

JVS: If you don’t recall the repertoire, we can just talk about your career. You’re a great man, and you’re a wise man.

MP: I’m an old man. I am wise through age. I played a lot, and I am playing a lot. That’s the most wonderful thing. You know, this last year I stopped the Beaux Arts Trio. The reason for stopping simply was that my young violinist, Daniel Hope, is starting an enormous career. He couldn’t give me any more of the time I need and have a viable career. The managers all said, you can take anyone. As long as you are in the trio, we can book it. But I felt I didn’t want just anyone, and I did not want something that was so beautiful at the very end – the trio really played well – to be replaced by something just to give concerts.

Then I found out I can have as many concerts right now as Pressler and Friends as I had before. I’m playing this summer I have a whole series of three concerts at the Metropolitan Museum next museum. So there are many, many avenues open to me to play and do what I feel I want to do – to make music.

JVS: So it wasn’t a case of, at your age, touring became difficult?

MP: No. Not in the least. I mean, it always was difficult. You know, planes not on time, and now especially you have to be there early because of security, etc. So, yes, it’s difficult. No it is not difficult, because it’s my raison d’etre. To be alive for me is to make music.

I do it in many ways. I mean, I play, but I also teach. I’m making music with my students, which is wonderful.

JVS: I heard you at the Florence Gould Theater in San Francisco the year before the trio’s retirement. It was miraculous. I know your sound from recordings, but there you were onstage, and you sounded like your recordings. It was that same miraculous

MP: [chuckles] I’m delighted to hear you say that…

JVS: That touch of the piano that is not obtrusive but is like a cushion of sound that supports the entire trio and gives it meaning.

MP: I’m delighted to hear you say that.

JVS: So we don’t know what the repertoire will be at Music in Deerfield on October 30?

MP: I think that is with the American Quartet: either Brahms or Dvorak.

JVS: Since you don’t think you’re doing a solo recital, how about talking about both of those pieces?

MP: The Dvorak is probably one of the most beautiful piano quintets. It uses every instrument sound-wise, I would say, in the most beautiful way. Its melodies are earworms. You can’t get rid of them. You hear one of those melodies, and the whole night and the whole day you will listen to that melody.

Brahms, of course, is a different story. He wrote the quintet after he heard Schumann. He loved and respected Schumann, and Schumann really loved him. Schumann called him “my young lion.†Brahms wrote his quintet under the impression of Schumann. It is grand. He didn’t even know that it would be a quintet. It seemed to him very big. It could be an orchestral piece, or for orchestra and piano.

He wrote it first for two pianos, Op. 34. Later, he wrote the quintet for string quartet and piano. It’s a wonderful work. It has a great first movement, a beautiful andante, and biting and driving scherzo, and a very, very beautiful last movement that starts out like late Beethoven. Brahms’ fixation was late Beethoven, because that was the most perfect music. He was always measuring himself up against Beethoven, and he felt he always came up short.

JVS: I want to ask about interpretations of Brahms. Once, when I did bodywork on people for a living, I had a compilation from Philips entitled Brahms at Bedtime. You of course will remember which piece it is, because I believe you were the pianist, and it has the movement that Brahms wrote for Clara.

MP: That’s from Op. 60. It’s the magnificent slow movement of the Piano Quartet in C minor. [Sings it.] It’s so beautiful.

JVS: I was so moved by it that I went to Tower Records to search for other recordings that would touch me in the same way as yours. The only one that I could find that was the equal of yours with Walter Trampler on viola was Rubinstein with the Guarneri. I listened to a lot of modern recordings…

MP: Yah…

JVS: Oh, you know where I’m going. I don’t even have to finish the sentence.

MP: No, no, no. It’s very hard to find one that is as beautiful as Rubinstein.

JVS: Is it because we’re in another era? Is it because…

MP: No. You can be in any era. You’re not in the era of Brahms. Rubinstein wasn’t in the era of Brahms either. His soul was sound, his way of playing the most beautiful, so he played the piece the most beautifully. They were a young quartet, and playing with them helped them immensely in their career. The beauty he brought with him, and he took it with him.

JVS: I’m going to teach a class on vocal appreciation. I was weaned on opera. I will go to a modern performance from Lucia or Rigoletto, and I’m…

MP: It’s boring.

JVS: It’s boring as hell. In my class, I’ll compare a modern recording with the Caruso recording I was weaned on. When they hear those few phrases… What has happened?

MP: No no no. You have to find the talent. Nothing has happened. It will happen the same way when this marvelous tenor who died. First of all, there was a Gigli who gave you just as many wonderful performances. And now there was the fat man who died…

JVS: Pavarotti.

MP: He could have given you the same thrill. And the Spaniard Domingo was fantastic.

JVS: Someone who is coming up is David LomelÃ, a young tenor from Mexico. The voice is gorgeous. If he does nothing wrong, the voice will be heard around the world.

MP: I believe it.

JVS: Is it harder for a great artist today because of all the marketing?

MP: It is much easier. They’re looking for it. They will market whatever is most marketable – if you can’t love the girl you love, you love the girl next door – but obviously they are looking for the great one.

JVS: But they put so much emphasis on those who look good.

MP: If they have everything, that will be great. Of course it’s great when a woman singer has a great voice and weighs 120 rather than 250 or 300 lbs. Of course they look for it.

JVS: I always get scared that the Montserrat Caballé of tomorrow will be overlooked.

MP: No, she won’t be overlooked. You saw on YouTube that woman from England who could have been nothing, but she had a beautiful voice and a half million viewers.

JVS: Susan Boyle. Did you hear what happened to her?

MP: She got second prize, I think.

JVS: As I was flying here, I heard that she checked herself into a clinic. The emotional pressure was too great.

MP: I believe it. The pressure took its toll.

JVS: Let’s say that we get people to your concert who have never been to a classical concert before, or who have only been to a few concerts. What would you tell them to listen for?

MP: I wouldn’t tell them what to listen for. I would simply say to them, find something that you like in what I’m playing for you. There are many things to be loved. I loved it all, and I’m playing it after so many years still loving it.

At this point in my life, I don’t play to have another concert or to have another fee. I’m well off as I am. I don’t need it. What I do need is to make music. In order for me to live, I have to play. So I’d say to them, start your discovery the way I did, and find something beautiful you love. Not only will it enrich your life, but it will also make you a better person.

JVS: Have you ever tried to deal with politicians and trying to get funding for the arts?

MP: From time to time I’ve met them. I’ve played for them. Sometimes I’ve been successful; sometimes I’ve not been successful. In the scheme of things, I’m not the one to meet the politicians. I’m the one to play the music and teach the music, because I’m at Indiana University, which is one of the music schools in the country, or I could say the world. Every week we have an opera performance. It’s unheard of at a music school. So I do have that outlet, and it is important.

JVS: One of the comments John Giordano made is that these are all young artists who will mature more.

MP: Yes or no. Of all the competitions, maybe still or two or three are still recognized. Yesterday I had a master class at the Texas Piano Institute, and there was Stanislav Loudenitch, who won eight years ago. He’s a magnificent pianist. You see, he didn’t make a career because he gets very nervous. A girl who was with him, Olga Kern, made the career.

JVS: I heard that one prizewinner became a Zen monk.

MP: I don’t know that.

I hate to tell you, but I have another 10 minutes…

JVS: I feel very sated. You’ve shared so much. Let me think for a second, which is always a dangerous thing.

MP: No, no, no. Not at all.

JVS: You mentioned that you played a piece by Bolcom with Richard Stoltzman that had a hip-hop movement in it. I’ve interviewed him and Joan, and they are such a delight.

MP: A delight. And he wrote it for me, I mean for my trio. We had a friend, a lawyer in Washington named Isenberg, who commissioned the piece. He plays the clarinet as an avocation. He said to me, ‘Let’s have a piece for you with clarinet.’ I said let’s have Bolcom, because I played one of his violin sonatas at the Library of Congress when the Trio was in residence at the Library of Congress. We gave 105 concerts there. When Bolcom wrote it, he said to Stoltzman, ask Menahem if he knows what a hip-hop is.

He did. And I was amazed he asked. I would have said, it hips and hops. So then he explained to me what that is.

JVS: Where I live in the Latino area, you can’t escape it. It comes through your windows, it sets off car alarms as people drive down the street. These kids think that amplified, distorted bass is real. So if the fender rattles…

MP: Then it’s good.

A propos judging, the first violinist in my trio used to in a famous string quartet in France called the Calvé Quartet. Whenever there came an argument in the quartet about how a phrase should be played, he would always say, everybody judges with his means. He meant it as an insult, but in reality it was true. You bring different judges, and everybody brings with him his past, his battle to learn the repertoire, his experience in performing that repertoire, his experience in succeeding more or less in this world. That is use when you are selecting somebody.

JVS: It makes me think of the debate around Sotomayor for Supreme Court justice. Of course she’s influenced by her background.

MP: She should be. It’s more to her credit how far she came. And it’s a credit to Obama for having selected her. The ones who have come in went so far to the other side, so to speak, that we need a voice that is moderate, and that sees there is a part of humanity that needs help.

JVS: I’ve been trying to get support for a program that would be classical music to the public schools and to at-risk youth. There’s one argument that we have to talk to kids in their own language, and speak the language of hip-hop.

MP: We need to guide them. Look. The best example here is Venezuela, that took the street kids, taught them instruments. You see the new conductor at the Los Angeles Symphony. Through this, his talent emerged. Abreu got the kids off the street to play a Beethoven, a Brahms, a Tchaikovsky, a Mahler. It’s wonderful.

JVS: Thank you, Menahem.