On June 12, 2009, the English early music choral ensemble Stile Antico made its much-anticipated U.S. debut at the Boston Early Music Festival. The entire concert debut was recorded by NPR, and can be heard online.

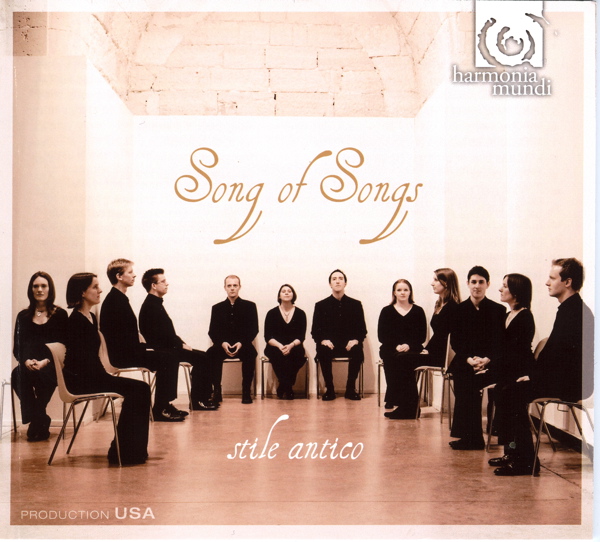

After Stile Antico won the 2005 Early Music Network International Young Artists’ Competition, the young ensemble’s debut disc for Harmonia Mundi, Music for Compline, won the Diapason d’Or, Choc du Monde de la Musique, and a Grammy Award nomination. Their second disc, Heavenly Harmonies, received the Preis der deutschen Schallplattenkritik and another Diapason d’Or. Attention from NPR, and a tour with Sting in Europe and the Far East in support of his Dowland lute song project, Songs from the Labyrinth, elevated them into company rare for an early music ensemble, and helped project their most recent CD, Song of Songs, into the Top 15 of the Billboard Classical Chart.

In anticipation of Stile Antico’s U.S. debut, I spoke by phone with one of the group’s founding members, towering bass Olly Hunt. Chief among my queries was the genesis of the group’s marvelously fresh, oft-sensual sound.

Jason Victor Serinus: I understand you all knew each other in school, mostly from Cambridge, some at Oxford.

Olly Hunt: Yes, and one of us knew the other from high school. There are a number of sisters in the group as well. But the majority of us were in the same year or two of school.

JVS: What is your age range now?

OH: Most of us are in our 20’s; we stretch from 24 to 35. The average age is 26-28. Since we began, a couple of people unfortunately left when we started becoming a professional ensemble because they had different focuses. They had what the British term a ‘proper job,’ and found that incompatible with the amount of work we did as a group. I think we started off with 12. We’ve still got nine of the original members after eight years. We’re quite pleased with that.

JVS: What were you singing when you began to perform professionally?

OH: Our first concert in Oxford, which was in 2001, was a very similar program to the Song of Songs recording. We’ve kind of come back to our roots in that way.

JVS: Did you sing for fun before that, or, when you first met, did you have as a goal to give a concert together?

OH: We always had the concert as a goal, because we thought then we had something to work toward and a climax to the five or so days of rehearsals that we would have together. Also, because we thought we would be able to put on a good show.

JVS: You must have been a pretty confident lot.

OH: The joy of the English choral tradition is that we can pick up a piece of music and read it, and know that we’re pretty much going to get it right. It gives us a lot more time to work on the interpretation and the fine-tuning of the piece, rather than making sure that all the notes are correct.

JVS: From that first concert, were you consciously shaping your sound to have an alternative to that chaste and pure sound that is associated with the Tallis Scholars and some other English early music choral groups?

OH: In some ways, the sound evolved because of the particular voices in the group. Gradually, particularly in the very expressive music such as the Song of Songs, we enjoyed singing much more with a warmer, more colorful palette. While we didn’t set out with a specific goal in mind, we matured and grew in terms of our sound as we sang more together.

JVS: When the three people dropped out and they were replaced, where did they come from?

OH: One we knew from University as well. A second was at Edinborough/ we knew him as well, and he would sing in a few of our concerts when one of us wasn’t around. One of the most important things about the group is us all getting on. The amount of time we spend together, we need to know each other very well. Especially since we do a lot of the administration ourselves, we need people whom we have complete confidence in. One of the reasons the group is flourishing as it is, we got together as a group of friends rather than picking the best singers we knew who might have had diva complexes the way many of us singers do. We’ve always been able to get along and put up with each other.

JVS: How many choral groups are there like you and The Tallis Scholars in the U.K. There’s The Sixteen. Are they actually sixteen?

OH: They’re normally 18, and sing predominantly early music as well. There a few small ensembles, such as I Fagiolini who sing one-to-a-part, and The Cardinall’s Musick do the same. But so far, it seems that everybody in the states knows The Tallis Scholars, whereas most people don’t know so much about the other groups in England. As far as we know, we’re the only group our size not to work with a conductor.

JVS: What is it like at this point in time to be singing music of the Renaissance? What is the relevance and importance of this music? What does it have to us now at this point in time?

OH: Wow. That’s a big question. With music, we’ve found so exciting that we’ve found so exciting about the response, particularly in the states, is how people, particularly who are often listening to this music for the first time, are profoundly touched. It’s lovely getting good reviews. But we’ve been reading people blogs, which is in some ways more important because we see what the public thinks. Some people write that they’ve never listened to this kind of music before, but it touches their soul. One person wrote that it had helped her through a difficult time in her life, allowing her to find places of stillness and tranquility. That’s one thing that music can really bring to your life. It takes you outside the humdrum everyday realities of scraping together a living and transports you to another world in some ways.

JVS: Thank you. It’s the only way I can stay alive. From what I understand, is it true that this music is similar to cathedrals and churches in Mexico that are built on the ruins of Inca and Mayan sites, in that the Christian Church took over these poems that were written centuries before the birth of Christ, and decided that the breasts were Mary’s?

OH: It’s an interesting one. The texts were thought to have been written by King Solomon, and were specifically erotic about the relationship between him and his lover. Since the birth of Christ – not that it was written to mean this – people have used the beautiful language of the text as a metaphor for the love of Christ for his people and his church. That’s the way that most musicians would have taken it.

JVS: So they were sincerely doing it, as opposed to wanting to set erotic texts but pretending that it had to be taken in a metaphorical sense?

OH: It’s always possible. Many Renaissance composers had a very mischievous sense of humor. I expect some of them did quite enjoy writing these slightly salacious texts as well. For example, Palestrina dedicated some of his Song of Songs to the Pope. He obviously had to say that they were Christian metaphor, even if he might have enjoyed the double entendres in private. Also, the language itself of these texts is so beautiful. You can see that whatever point of view the composer was coming from, the texts inspired them to create wonderful colors in their music.

JVS: All these pieces on your disc were written as stand-alones, rather than excerpted from longer works.

OH: That’s right. They’re all short motets.

JVS: Were they usually performed in church settings?

OH: Yes. They were intended for the church, for example, as an anthem in mass. Yes, there were madrigals if you wanted to perform salacious texts at home. But these were all intended for church.

JVS: Was it all men, boys, and castrati singing these?

OH: It would have been all male choirs in the church. St. Peters in Rome had an amazing choir with a lot of fine boy trebles. Countertenors sang the alto line.

JVS: They didn’t have castrati in their choirs?

OH: No. The castrato ended up being just an operatic voice as far as I know. When the operation was had, and the voice then matured, it was often very powerful with quite a big vibrato. Just as an operatic soprano wouldn’t be so suitable for St. Peter’s Church, the castrato is in a similar vein. The sound is very different than a countertenor’s. David Daniels, for example, sings with the same technique as male altos in a choir did and still do today. The castrati, having had the snip, have voices that develop in a very different way because of the lack of testosterone.

JVS: When you’re performing at the Early Music Festival, what size will the venue be?

OH: They haven’t announced the venue yet. With any luck, it will be somewhere with a decent acoustic.

JVS: Did you all have a sense that you were as good as you are and that your first CD might win multiple awards?

OH: Absolutely not. We’ve been completely overwhelmed by the response to the CD, particularly from America. The response has been extraordinary. We were blown away when things really began to rocket. It really seemed to capture the public imagination. Not that many discs do.The success in part is thanks to the review it got on National Public Radio. It really hit the public’s consciousness. But we came into this recording music that we enjoy singing in the way we enjoy singing it. We weren’t expecting any particular response. We hoped it would be successful, but we had no idea that it would cause a storm in the way it has.

JVS: Which NPR show were you on?

OH: Tom Manoff. I don’t know the name of the show. [Probably All Things Considered].

JVS: In San Francisco, the main public radio station is 24-hour talk. It probably never played here, which is just crazy. Have you been to Asia at this point?

OH: Not on our own. We were lucky enough to be with Sting in the Far East in December. We haven’t been to Asia yet, but we’re hoping to get out there at some point. In December, we met up with a Japanese agent who’s interested in working with us. We’re hoping something will come of that.

JVS: What were you singing with Sting?

OH: We were doing classical back-up choir of the Dowland that’s on his CD.

JVS: Were the songs written for a choir in back?

OH: No. Actually, a lot were just written for solo voice and lute. But Dowland himself did write choral parts as well. So it was an authentic performance for people who worry about that.

JVS: Was it a success?

OH: It went incredibly well. It was fascinating for us playing for those sorts of venues that classical musicians are just not used to. I got an impression that some of the people in the audience were Sting fans who would come and hear Sting no matter what he would sing. They started by not knowing what was really going on, but ended up really enjoying the music. Then there were other people who were probably classical music fans who came to see what Sting was doing to Dowland, and I hope ended up being pleasantly surprised. Sting really has something to bring to that kind of music, singing in an earthy troubadour style rather than with the clarity and precision that you get from voices such as Emmy Kirkby’s. It’s a very different interpretation, but one that is very valid I think.

JVS: I often wonder, when I listen to the impeccable musicianship of Jordi Savall and Montserrat Figueras, if early music sounded anything so polished back then.

OH: It’s a fascinating question. We always wonder the same as well. I think they probably always had different goals in mind. They might have incredible singers, and they might have been slightly ropy. It’s very tricky for us to tell now, isn’t it?

JVS: I assume you were all amplified?

OH: Yes. The interesting thing for us was to try to modify our sound to blend with him rather than sing as we always do. He’s always microphoned, and we needed to be as well in such a large venue.

JVS: How many concerts did you do?

OH: That tour was around 12 concerts: four in Australia (Sydney, Brisbane, Melbourne, and Perth), Malaysia, Hong Kong, Singapore, and Japan. It was a fantastic month. The venues were usually 2-4,000 seaters. We usually performed in classical venues, but in the big concert halls.

JVS: Did young people rush up to you for autographs afterwards?

OH: Not so much afterwards. It was more like young people rushing up to us to ask if we could get them Sting’s autograph. But that’s still vaguely important.

JVS: They weren’t tearing your clothes off.

OH: Not yet.

JVS: You’re still young. There’s time. What are your goals in terms of future repertoire? Do you want to stick to medieval/Renaissance music, or move beyond it?

OH: It’s something we’ve considered. Basically, we want to stick to what we’re good at. We want to sing music that we feel we have something to say about. If that can include modern music, then that’s absolutely fine. The only thing we’re slightly wary of is that there are some excellent groups already around who are doing a lot of modern music and really specialize in it. We don’t want to do similar music to them but not quite as well. Whatever we want to do, we want to do to an excellent standard.

In the Three Choirs Festival later this year, we’re doing a commission by John McCabe. That will be very interesting for us. We have to choose our modern repertoire quite carefully, because doing some modern pieces un-conducted would be very demanding, to say the least. Generally what we look for if we’re interested in modern music is music that is inspired by or is based on Renaissance music so we get a bit of coherence in the program. John McCabe’s piece, for example, is the text of “Woefully Arrayed,†which was also set by William Cornysh. McCabe is revisiting the text from a modern perspective, but is inspired by the old world.

JVS: And your long-term goals are what?

OH: At the moment, we’re consolidating the incredibly rapid progress we’ve somehow made in the profession. In terms of the next few years, we’re spreading our wings in terms of places we perform in. Obviously, coming to the States has been a huge goal for us. From the time we started out, we’ve thought it would be wonderful to tour America, particularly since we’re recording with Harmonia Mundi. We’d like to have a tour of the States once a year, which would be fantastic. This music is sometimes neglected outside Europe. We want to bring it more places. Our trip to Lebanon, for example, was very exciting. We didn’t know what to expect at all. It’s an incredible place historically. Basically, nobody in the audience had ever heard this wonderful music before. We really felt privileged to be ambassadors for it.

JVS: How wonderful. Did you get wide coverage?

OH: We got newspaper coverage. The venue itself was quite small, but they want us back next year in a bigger venue to try to spread the word a bit wider. We’re coming out the East Coast again in October to do a few more concerts. We hope to get a West Coast tour the year after.

JVS: Is there anything more you want to say to your readership about this upcoming concert?

OH: People might be interested in the details surrounding not being conducted. The main reason we got together as a group was so we could make our own interpretive decisions about this music, rather than doing what the person in front told us. We’re not creating a sound that one single person decides upon; rather, we’re all contributing our own experiences, our own training to it.

Within the group, we’ve got a number of conductors, a number of full-time professional singers, and a number of teachers. From that, everybody is able to bring slightly different things to the interpretation of music. As a singer myself, I often think of musical repertoire from the point of view of lieder singing, and how would you interpret the words. What emotions are behind the character of the music, which is something that we’ve all found that might be lacking in most performances of early music. Most people seem to concentrate very much on cleanliness and purity and beauty of tone, which can create a wonderful effect. But we try to add a bit more expressivity to that.

Not being conducted obviously means that we have to have many more rehearsals than most groups, as it’s very easy to follow someone who is in front. We have to have all our rhythmic clocks working very, very hard to keep the ensemble together. We have to listen very hard to each other to keep the tuning and the balance together. It’s a much more demanding way of working, but one we find far more satisfying in the long run.

JVS: You all have other gigs?

OH: Absolutely. We’re not so successful that this can be an entire living, unfortunately. It’s something we have to balance very carefully in the group. We have some people who teach in schools, so doing concerts on holidays is much better for them. Some do operatic performances as well, so getting the group together can be difficult. We try to make it as much of a priority as we can.

JVS: Do you personally sing opera?

OH: Yes. I basically do as many different types of singing as I can. There’s a big church scene in London, so I sing in many services there to earn my keep. I also do opera and solo concerts and song recitals – as many different forms as I can manage.

JVS: Do you open the vibrato in one medium, and keep it far more in control in the other?

OH: That’s right. Some people find it very hard to change between styles that way, but I personally find it very useful to get to know your voice. If you have that much control over what you can do with it, you can bring aspects of one discipline to another.

Again, we probably use more vibrato when singing Early Music in our group than, say, The Tallis Scholars do. But we use it with an expressive aim in mind. It’s not an operatic style coming into Early Music, but it’s the expressivity that something like vibrato can bring in opera that feeds into how we sing in Stile Antico.