CL Hey Mark, thanks for taking the time out of your schedule to talk. I will warn you upfront that I am not a professional interviewer, so please bear with me!

MW (laughs) My pleasure, not a problem at all. I appreciate the opportunity to bring some attention to my new book.

CL What’s been the initial response to “Music and Audio?” I know that I just recently got my copy. Have you had much feedback yet?

MW Yes. The initial response has been exceedingly positive. Much of it from customers telling me how nice it is to have someone outside of the mainstream audiophile press, who doesn’t have to cater to a wide audience with reviews and product hype, put together a comprehensive and honest book about high-end audio.

CL The book IS extremely comprehensive. It’s basically audio from soup-to-nuts, and yet it’s a very approachable and enjoyable read. Not what you’d expect from something over 800 pages long!

MW That’s exactly what I was going for. By comparison, Ethan Winer’s book, The Audio Expert, is somewhat dry and technical. In writing my book, I tried to fuse both musical and technical perspectives, but from the production point of view. You know, audio writers cover the delivery end of audio, which is all well and good. Given my engineering and production background, I simply wanted to add to the conversation by looking at every stage of an audio production. I wanted to discuss things like what actually is involved with making a record and how the decisions we make throughout the production and mastering stages affect what you, the consumer, hears when you press PLAY.

CL It’s interesting that you say that. As audio press, we do tend to focus mainly on how to extract that last bit of performance from our systems, primarily through our system components, room treatment, etc. But no matter what we do, we aren’t ever going to hear more that what was already captured and released by the record company. You’re saying that the biggest improvement to be had in perceived fidelity will come from improving the quality of the recordings that we get.

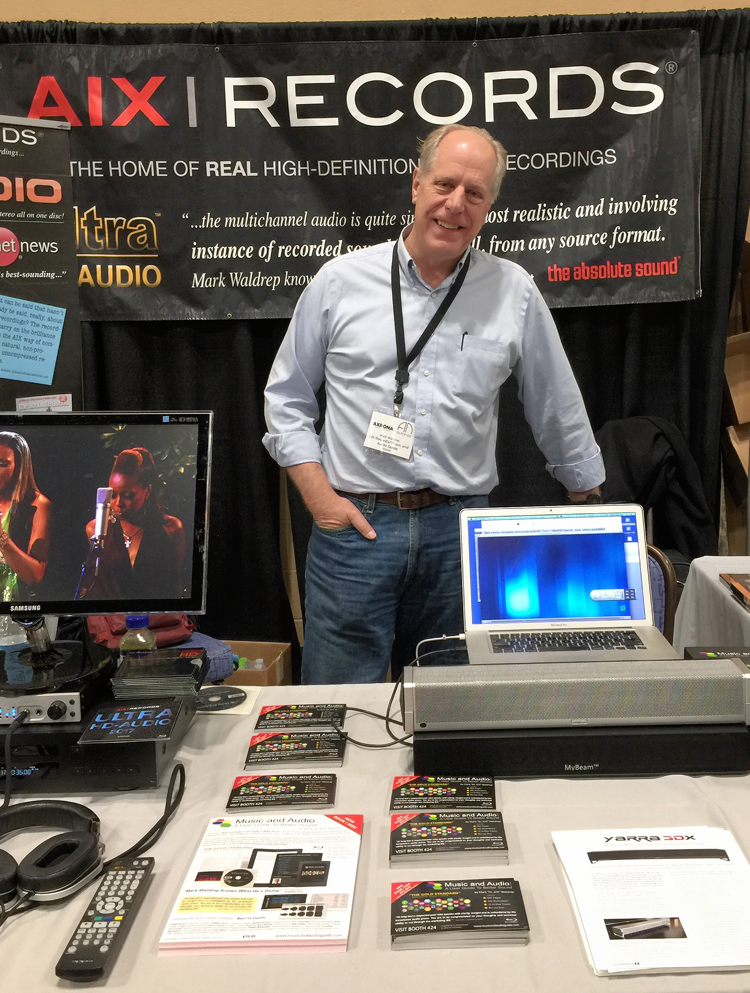

MW That’s exactly right. That’s been my life’s mission since I started AIX Records almost 20 years ago now.

CL In all honesty, having had a chance to go through the whole book now, I think it should be retitled to something like, “How to Be an Audiophile: No BS, No Waiting!”

MW (Laughs)

CL I mean you’ve broken down the entire audio recording and playback chain, gone into extreme detail and given plenty of background history as to why things are the way they are. You’ve also given good advice as to how things can be improved at both the production and playback end of things. There’s also interviews with other audio industry experts and a dedicated Blu-ray disc that comes included. The book has a lot of deep technical material throughout, but its written in such a way as to make it all easily understandable and enjoyable. Your teaching background definitely comes through in the writing.

MW Thank you.

CL So, what made you decide one day to start putting this sort of project together?

MW I wanted to find a broader platform, beyond my regular blog posts at RealHD-Audio.com, to confront and clear up a lot of misconceptions and bad advice about audio. Mostly false information that has gotten passed either over the Internet, through forums and audio publications that just isn’t accurate. The project itself was inspired by Jim Smith, who ran a Kickstarter funding campaign for a new book about audio. I’m familiar with Jim’s work — he is one of my readers — and I’ve followed his work for a number of years. He had a very successful campaign and raised a good deal of money for his as yet unfinished project. Jim’s expertise is on the consumption side of audio — room acoustics and staging. He gets involved with system set up, room tuning, equipment choices, etc. His campaign’s success inspired me to write Music and Audio: A User Guide to Better Sound. And, frankly, there are too many books out there written by senior audio writers that contain information that is just plain incorrect. Something as simple as the correct speaker layout for 5.1 surround music playback, for example. One book I know of references a 5.1 speaker placement that ignores the ITU standard — and then complains about my surround mixes! You might be able to get by with an alternate setup when listening to movies, but it’s not what we use, and mix for, in a professional music studio. A little bit of extra research on the author’s part would have helped. As another example, he suggests ridiculous things like using expensive designer cables to adjust the fidelity of your system. It just makes me shudder when I read stuff like this! It’s just flat-out wrong! So, I also took that situation as somewhat of a challenge.

Secrets Sponsor

CL To put together something rooted a little more in reality?

MW Yes. I wanted to counter the subjectivist, “feel-good” audio mentality that is so prevalent in audio reviews and articles. Something that was backed up with facts gleaned from actual experiences while engineering records, studying computer science, teaching audio and producing high-end surround productions. The proof is in the listening! That’s why I included the disc as part of the package. In the end, it turns out that it’s less about the equipment, or the cables, or the power conditioner you use in your system and more about what it takes to produce a great sounding recording. That and the acoustics of the room that you are listening in makes the lion’s share of the difference.

CL It took you some time to get the book put together after you met your funding target. How come?

MW Well, initially I thought that I could write about a chapter week. That turned out not to be true. It actually took me 2-3 weeks to complete each chapter, and then it took another 6 months to create the illustrations for this thing. There are almost 300 illustrations in the book and I did all of them. Add to that, designing and authoring the Blu-ray disc and it quickly grew into a time-consuming monster of a project. Additionally, I was set back due to a brief — and surprise — battle with Thyroid cancer. Thankfully all of that worked out well.

CL So, do you think you covered it all?

MW I believe, from the feedback I’ve gotten, that I accomplished that task. It’s a no-BS book. Whether you agree with me or not, I don’t offer anything in the book that I know is untrue. I may miss a detail here or there and I may not be up on the latest aspects of server technology or Bluetooth connectivity, but I have lived the last 40 years of my life in the music business, on all sides of the production process, so I think I have something valuable to share with the audio community.

CL Speaking for myself as an audio reviewer, I know we tend to focus on the hardware side of the equation because that’s the focus of our job. We review gear. As a producer/engineer, it’s only natural that your book would focus heavily on the musical content end of that same equation, but you devote a good deal of space to playback hardware too.

MW I definitely wanted to write about audio playback in the book. In that sense, it’s similar to what other writers have done. But I wanted to use my experience and background to help flesh out what to look for in various components, outline setup best practices for speakers, etc. I think it lends a different perspective on the subject than what someone might otherwise read in the audiophile press. But whereas a reviewer might say; the most important part of a high-end playback system is the speakers, followed by the source component, the amp or whatever, my experience tells me that the most important part of an audio setup is in fact the recording, followed closely by the speakers and the acoustics of the room you are listening in. It may sound slightly self-serving, coming from the owner of a record label, to say that the recording is the most important component, but I devote a good deal of time and energy in the book to explaining why it’s true. Your system can really only work with what it’s given, and it can’t create fidelity that isn’t on the source recording. In regard to acoustics, if you aren’t listening to your system in a space that has been properly treated or, at least, had the most significant acoustic issues addressed, then no amount of money that you spend on equipment is going to overcome that. A room that has obnoxious resonances and skews imaging due to things like glass walls, padded furniture or hardwood floors obviously degrades the sound that comes from your speakers. Your system cannot operate at its full potential without a complementary room.

CL One of the things that immediately struck me when reading the book is how you are able to take a lot of the dry technical, audio theory stuff and make it approachable and easy to understand. You actually were able to get a cartoonist (me) to understand subjects like dithering and Fast Fourier Transforms. Who’d have thunk it?

MW That certainly was the hope. Thanks. And it’s important to understand that while it may not be necessary for the average audiophile to understand those topics, the people who design the equipment and those of us who use it to maximize our fidelity — when warranted — we really do have to know about that stuff.

CL The inclusion of a section on music theory was also interesting and very informative. It was a great little crash-course for someone like me, who loves and appreciates music but can’t play an instrument to save his life!

MW I included the section on music theory because I have a PhD in music composition and studied the subject at length. I wanted people to understand that there is an intelligence, a system and a theory to music. Things like harmony, rhythm, and melody all contribute to this amazing art form. And I think the more you understand this, the easier it is to see that people who are composing classical, or pop, or jazz, or any of the other styles of music, are using a common vocabulary to express different genres. Some of that vocabulary is more aggressive — strident or dissonant — than others. The Stravinsky example (in the book) from The Right of Spring uses polytonality, simple chords are stacked a half a step apart from each other. It makes for very powerful music, but these are also the same E-Flat dominant 7th chords that Hank Williams used when he wrote country tunes, or that John Lee Hooker used when he was playing the blues. It’s that overarching concept that inspired the title of the book, Music and Audio. You can’t just talk about high-end playback systems. You have to first start with the raw material (the music) and work your way through all of the subsequent steps.

CL I personally found the included Blu-ray disc to be particularly valuable. Especially the sections where I could switch between different levels of compression, or lossy encoding, or mastering techniques. It’s one thing when you listen to an overly compressed song in isolation. But when you can instantly switch between varying levels of compression, for example, on the same song while it’s playing, you’re able to deliver the “Ah-Ha” moment.

MW The disc and the part of the book that corresponds to it, I feel are particularly strong and unique. The first chapter is almost 100 pages and took me six months to put together, what with all the diagrams and in-depth analysis of each of the sample tracks, comparison, and test tones. The disc had to be put together because it’s one thing to talk about and back up the information and concepts I wanted to relay, but if I could get the listener to experience high-resolution audio and those comparisons as well, that would just close the circle. The Blu-ray disc allows readers to actually hear what mastering does, what normalization does and how music heard on the radio is over-compressed. In a sense, it actually proves the vinyl guys assertion when they say we had it better back in the day — not new vinyl but the old vinyl — was actually more dynamic, had more fidelity and tone than the limited fidelity files we get today. I included 12 of my own high-resolution tracks to demonstrate just how good music can sound — if you focus on fidelity during the production process. I wanted people to be able to just sit down and listen. Hopefully, they will experience the same epiphany moment that so many folks who have come to my demo surround setups at AXPONA or other shows have experienced.

CL I also think it’s fair to say that someone who reads this book is going find out very quickly, and very clearly, how you feel about various subjects that get brought up among the chapters.

MW (Laughs)

CL I mean there is no question that you have strong opinions about various, and sometimes controversial audio subjects. Yet you go to great lengths to back up what you believe and why. And all of it is derived from your experience and supported by grounded, factual knowledge.

MW Well look, it’s just not worth it to visit a blog and start ranting and raving against others with different perspectives. Because, ultimately, when people come down to that pissed-off, walk away point in those conversations, ninety percent of the time what you’ll hear from a subjectivist audiophile is “it just sounds better. I like it, so go away!” I certainly appreciate that people are going to like what they’re going to like and that’s going to affect a lot of things in their life including their audio preferences. But, if you’re a DSD guy for example, I’m going to want you to know how limited a 1-bit encoding system really is. So, running around saying that this is the newest “analog-like” digital format that’s going to take over the world because it sounds so much better, is just not factually true. The same thing is true for the new MQA format…

CL (Laughs) I was going to ask you about that later but, go ahead, tell me how you really feel!

MW People need to realize, first and foremost, the music industry is a business. It’s a business for Robert Stuart of Meridian and MQA, it’s a business for Synergistic Research and AudioQuest, it’s a business for all these people that show up at the trade shows. And while it may be a fun thing to be involved in, at the end of the day companies need to return a profit or they’re out of business. With that in mind, if I can sell you something that you believe is an enhancement to your system or is something that you enjoy, all while allowing me to make a profit, then so be it. But we have to address the science or technology behind new approaches or formats. And you have to survey experts and researchers and arrive at your own conclusions. That’s what I tried to do by including a lot of the back-and-forth with people who have challenged my positions over the years. I talk to people like John Siau of Benchmark Digital, who is an absolutely brilliant analog and digital design engineer. I listen very carefully to other folks as smart as him. I know and have been friends with Robert Stuart for years, but the realities of what he’s trying to pull off with MQA just don’t add up for me. So, drawing on my own experience plus what a number of others who are smarter than I am are saying, it appears that MQA is more of a business play than exciting new audio format. I believe it solves a problem that doesn’t exist.

CL So, you think it’s more of a Digital Rights Management/licensing scheme?

MW Yes, and more. When I see MQA being adopted by Universal and by Sony and being used by various hardware manufacturers, it’s protectionism. These companies are reticent about giving you the ultimate listening experience from their masters, they’re giving you the MQA version which they claim will provide a better listening experience than what you’re getting now. The labels love it because they get to sell you a new version of something you probably already own in several different iterations. MQA loves it because they charge a royalty fee on every step of the production process — through hardware and software. And consumers are left unconvinced through a sort of Shock-and-Awe campaign. MQA proponents will say “Doesn’t this sound great?” Well okay, sure it does but play me the original version because that sounded great, too. MQA’s ability to stream high quality audio through a low bandwidth device and have it sound as good as AIX’s original hi-res stuff would be great. But it doesn’t do anything for popular music from Bruce Springsteen, or Beyoncé or Kanye. All of their tracks don’t have anything in them that benefits from being folded into MQA’s “Music Origami” compression scheme. It’s a closed system that can be accomplished by other non-exclusive means.

CL To this day, I have yet to hear an A-B comparison of an MQA encoded track versus a non-MQA version so that I could make a proper judgement for myself. I’ve heard plenty of MQA material at audio shows, in absence of anything to compare them to, they sounded fine.

MW Four years ago, I had lunch with Bob Stuart and he asked me to send him some tracks which he said he would encode with MQA so that I could make my own comparison. I sent him the tracks. I know he’s got them, he was very complimentary about their sound quality. I’m still waiting to get the MQA versions back. Anyhow, it’s four years later and I’ve stopped asking about them.

CL What do you think you would find if you ever did get those encoded tracks?

MW If got them back and I was able to analyze A (MQA encoded) vs B (original) I would find that one was lossy where the other was not. The encoded file may have less bandwidth for easier streaming, but we can currently use FLAC to do streaming unfold/decoding and maintain the same quality at the receiving end that I’ve got in the original, without using his new expensive method.

CL Is this what we’ve come down to in the music and consumer audio industry? The reliance of smoke and mirrors in order to keep selling music and gear?

MW It’s amazing that this continues to be a business full of opportunity. But maybe we ran out of new and exciting things to do with technology in the quest for better sound a long time ago. Ten to twenty years ago, in fact. If I can equal or match the fidelity of a real-world listening experience, then we’re there. And we ARE there — now. However, the music industry chooses not to go in the direction of better fidelity and immersive, surround sound. They refuse to stop over-compressing and making things excessively loud. So, what does that leave the hardware and software makers to work with? People consume their music on headphones, earbuds, Alexas and HomePods these days. So, in my mind, the only two things that are left to be changed are the listening environment (that’s where my work with the YARRA 3DX soundbar comes in) and the actual content that we listen to. My motivation for creating AIX Records was to demonstrate that it’s possible to make, present and make a profit producing recordings that are superior to CDs, vinyl or any of the other delivery formats out there. We have the ability now to make and inexpensively distribute recordings that meet or exceed human hearing. I think the option should be there, for those of us who appreciate it, to be able to acquire material like that.

CL Well, it’s not hard to see how your candidness about the industry may not have won you many friends on that side of the isle.

MW I have become a contrary voice in high-end audio. I have strong opinions and therefore I get a certain amount of pushback from all corners. However, it’s also true that there are many thousands of people out there who have written or spoken to me and said “Finally, a little fresh air. A little honesty.” And this business doesn’t have a lot of that for reasons that are pretty obvious.

Thankfully, I’m in a position where I don’t need to push an agenda, stretch the truth or use hyperbole to pitch ideas that I’ve favored during my 40-year career. Look, I have an up-side if I sell some books, for sure, but my life is not dependent on my being a successful author or record label. I’m a college professor and I run a successful post-production facility — and I even lease out parts of my building for additional revenue. I don’t need to exaggerate. It’s well past time that a new reference book or resource came out that offers another perspective to the kind of information one finds in mainstream audio publications or other books on high-end audio.

CL Do you feel that the market for high-resolution music, with or without surround, will ever find appeal with anyone outside of just a niche crowd?

MW That’s a hard one to answer when you say “ever.” It is now conceivable, with metadata, to have your playback device, be it your cellphone, your streamer or your DAC perform the final music mastering, on the fly, at whatever degree of severity that you want. That’s never going to happen because the record labels don’t want multiple SKUs and mastering engineers are making a living squashing dynamics and making their tracks louder than others. But imagine the day where someone has made a recording that has all that ultimate fidelity (akin to what I’ve been doing for 20 years) and that is delivered out to the end user. If he or she is listening to it on their audiophile setup at home, they can set the mastering level on their DAC or playback device to “0” for maximum fidelity. Whereas if you’re driving on the road with your windows down and listening to that same track, you’d want to set the mastering level to say “10” or even “11” to compensate for the wind and environmental noise. That kind of processing can be done at the end. It can even include binaural processing or 3D processing and a whole host of other signal processing that didn’t exist back when we were making records using cutting lathes and analog source tape.

There are a whole host of possibilities out there, but I am fairly reserved in my optimism for the music industry because the music industry is into making money and they are going down the path of louder-is-better and two channels is enough. A lot music mixes these days are even being folded to mono because that tends to work better on airplanes and networked speakers like Alexa.

Secrets Sponsor

I think there are ultimately two opposing worlds, those of us that can appreciate the best, whether it be food, golf clubs, wine, or music and then there is the rest of the world who don’t really care. High-end audio will forever exist as a niche market. There are both fewer and fewer high-resolution and surround sound recordings being done. Hollywood, Burbank or wherever you want to say the center of the music industry is, are not even recording masters in 96k-24 bit no matter what they tell you. They’re all working at 48K-24 bit or maybe some multiple of 44.1K because they out-process their plug-ins to do all the magic in Pro Tools. This means if you double your recording’s sampling rate, you essentially quadruple the processing power required. Now in a practical sense, recording at 48K/24 bit gives you everything you need to make a good recording, but 96K removes any shadow of a doubt that you’ve captured everything. So, I say let’s record and deliver at 96K/24 bit and if the recording needs to be down-sampled it can be done in the end-user’s playback device.

CL So, what did you make of Neil Young’s whole push with PONO a few years back and his push for better quality music?

MW Sadly, even people that are in the business, professionals that are both artists, engineers and mastering people haven’t heard how good real high-resolution music can sound when done right. They haven’t heard it, so they don’t know it. I got chewed out by one of these folks once. They were saying “Well how can you criticize Neil Young? He’s Mr. Audiophile!” I guarantee you that Neil Young has never heard, NEVER HEARD anything that sounds like my recordings. I know his people have. I know his former engineer, I know his producer and I know the guy who helped him with the PONO initiative, John Hamm. John flipped out when he heard my stuff and promised to play it for Neil, but I later found out that he never did. Neil likes that grungy, distorted analog sound. And that’s fine, it’s a flavor, but doesn’t mean it’s necessarily an audiophile goal.

CL But for Neil Young’s style of music you wouldn’t need better than a good 16 bit/ 44.1 kHz recording to cover the musical content completely and accurately, would you?

MW That’s right! That’s absolutely true.

CL Beyond the problem of there being a music industry who are too set in their ways to change, we also have a society that listens to their music mostly through portable devices while on the go. And when they’re at home they are most likely listening when performing some other activity. Most of us don’t sit down for an hour or two anymore and just enjoy the music. How do you convert people like that to wanting a better experience but maybe not the complexity that may come with it?

MW That, in a nutshell, is why I got on board with Comhear and consulted on the development of the YARRA 3DX beamforming soundbar. This soundbar, and the accompanying small subwoofer, will create an effective 5.1 surround sound field when placed at a computer workstation or set up in a small apartment. All for about $600 bucks. This new beamforming sound field modelling technology that is used in the YARRA really changes the paradigm of delivering sound from speakers to ears. If my goal is to provide a high quality 5.1 surround sound musical experience with aggressive mixing, and I know that the entirety of your audio experience is going to be comprised of what sound waves arrive at your two ears, then I can model that experience and use the beamform technology in the YARRA to effectively deliver that. This technology even allows me to adjust the modelling of the acoustic energy so that you think you are listening to, oh let’s say, a set of Wilson or Magico speakers, if you like. When we combine this technology with a motion tracking sensor, then we can more fully and accurately recreate what will happen, acoustically, in a live situation. This would be my goal, but sadly that’s not the goal that the music industry is either focused on or interested in.

CL What do you make of the resurgence of vinyl in the marketplace?

MW I think it’s one of those niche things that is driven more by a sense of nostalgia and a certain cool factor more than anything else. Speaking of vinyl, one thing that I recently discovered (and I point this out in the book) is that the RIAA phono EQ curve is not defined past 20 kHz. There is no electrical specification or protocol for it past 20 kHz because no one considered that necessary. This morning I was reviewing some music files for a tribute album project that I am working on, and there is plenty of beyond 20 kHz frequency information on these well mastered recordings that I am working with. To simply chop it off at 20kHz means that your ears are missing information that they would otherwise get if you were listening to that same ensemble in a live situation. Why shouldn’t we include ultrasonic information if we can? It doesn’t cost us anything more and there’s no downside provided your playback chain can accommodate that. The RIAA is not that type of playback chain. Vinyl was a good but not great playback medium. It has certain advocates who rightly point out that, at its beginning, CD’s sounded harsh because they were rushed to market and were poorly mastered, making the vinyl sound less compressed and more natural. And even now, well maintained classic vinyl cut from analog masters can sound more natural and less compressed than what some of the studios are putting out today, digitally, in their all-out loudness war. While there are real things that do make vinyl attractive to people, today the fidelity provided by a well recorded 24-bit 96 kHz PCM file will trump anything played from, or recorded to a file from, vinyl, period. Look, I grew up enjoying the sound of vinyl from my AR-100 turntable, played through my ElectroVoice speakers and hand built Heathkit receiver back in the day. But we’ve moved on. If sound quality is your goal, not nostalgia, then people should abandon vinyl and not go back.

CL In your career in the music business what are the moments that you are most proud of?

MW There are a few of them for sure. I’ve been fortunate enough to have been able to work with a lot of great personalities over the years. I could not have been prouder to work with and record Elliot Carter’s piano trio in New York many years ago. The man was a big hero of mine and there he was, at almost 100 years old, calling out the third measure of the second bar and telling me the second beat had a bad note in it. I was lucky enough to have my string quartet selected by Maestro Pierre Boulez for a Master Class at UCLA. Working with Willie Nelson on my Paul Williams project was also very gratifying. Sonically for me, when someone asks me, “What are the high points in your catalog? What are those tracks that will instantly convince me on what you’re talking about?” I would say The Latin Jazz Trio tune Mujaka (which is on the disc) is just magic. Laurence Juber and John Gorka, as well, were two musicians who really stepped up and brought added creativity to the table to match what I was trying to achieve sonically. Those are some of the moments with AIX Records that will last for me.

CL So, Mark, as a quick ending question to wrap up our interview, how do you really feel about boutique power cables?

MW You will experience a greater timbral change in the sound of your system by moving your head six inches from your usual listening position than you will get from any expensive designer power cords or interconnects. It makes me shudder to think that people spend money on stuff that doesn’t matter.

CL Mark, it was great to talk to you. Thank you so much for your time.

MW It was my pleasure Carlo. Thank you.