Miguel del Aguila Salón Buenos Aires Bridge 9302

- Performance:

- Sonics:

On November 11, we learned if Clocks, a 19-minute composition on Bridge’s recent CD devoted entirely to the chamber music of Miguel del Aguila, won the Latin Recording Academy’s Grammy Award for Best Classical Contemporary Composition. One of two CDs I’ve reviewed for Secrets that contains music nominated for a 2010 Latin Grammy – the other is Antonio Lysy at the Broad (Yarlung Records), whose rendition of Lalo Schifrin’s Pampas was also up for Best Classical Contemporary Composition – Salón Buenos Aires is filled with irresistible music.

Del Aguila wrote Clocks as a commission for the Ventura Chamber Music Festival, which engaged the composer and Cuarteto Latinoamericano for the 1998 premiere. Here performed by Camerata San Antonio, and recorded with rather bright, upfront sonics, Clocks takes the listener on a fanciful tour through a clock museum. Each movement represents a single timepiece (as in the fourth movement, which receives its inspiration from a Sundial of 2000 B.C.), a group of them, or a story told by clocks.

Clocks is one wild ride. Somehow, four chamber musicians, including Kristin Roach on piano, manage to hammer, chant, bang, and saw their way through a bizarre assortment of mechanical sounds, zany effects, charmingly antiquated melodies, thoroughly modern mish-mashes, and ecstatic excess.

“While writing this work,†del Aguila proclaims in the liner notes, “I tried to avoid the expected piano quintet sound and Brahmsian drama. As it often happens with my works, the element I strive the hardest to obtain is the one the press misunderstands. At its premiere, a Los Angeles Times reviewer objected that ‘it didn’t sound like a piano quintet.’â€

Except for the ending of the last movement, “The Joy of Keeping Time,†which juxtaposes distinctly Latin rhythms with a short, concluding Brahmsian romantic flourish that over-winds itself until its springs pop, Clocks doesn’t sound in the least like a traditional piano quintet. And that’s just fine. It’s hard not to love this zany work.

The CD also contains four other compositions: Charango Capriccioso (2006), Presto II (derived from the last movement of Aguila’s String Quartet No. 2 of 1998), Salôn Buenos Aires (2005), and Life is a Dream (2002). Most of these merge quintessentially Latin sounds and rhythms with modern compositional techniques. Sometimes the sounds are distinctly Argentinean; in Life is a Dream, the Spanish flamenco atmosphere of Pedro Calderon de la Barca’s 17th century Spain emerges.

The title work, Salón Buenos Aires, paints a portrait of the city in the 1950s, during a time of prosperity and optimism that preceded the political and social collapse and repressive dictatorships of the 1970s. The work is far deeper than you might expect. The charango is irresistibly lively, the Presto II a zip mix of classic jazz and Caribbean elements that mocks the Viennese tradition. Traditionalists may not approve, but those with a spirit for adventure and rhythm will kick up their heels and stomp with delight.

Charles Lloyd Quartet Mirror ECM 2176

- Performance:

- Sonics:

For fifty years, Charles Lloyd’s excursions on tenor sax, flute, and alto sax have defined the inner and outer limits of jazz. Inner, in that Lloyd journeys to an inner sanctum reserved for the few, from which originates a language very much his own. Outer, in that in his hands, the simplest of ballads can become flights into unchartered territory, and familiar melodies mere launching pads for far out excursions.

Born in Memphis on March 15, 1938, Lloyd received his first saxophone at age 9. Raised on radio broadcasts of the music of Charlie Parker, Coleman Hawkins, Lester Young, Billie Holiday and Duke Ellington, the teenage Lloyd was already playing jazz with saxophonist George Coleman and working as a sideman for Johnny Ace, Bobby Blue Bland, Howlin’ Wolf and B.B. King.

As a Master’s student as USC, Lloyd studied with Halsey Stevens, an authority on the music of Béla Bartók. At night, he performed with Ornette Coleman, Billy Higgins, Scott La Faro, Don Cherry, Charlie Haden, Eric Dolphy, Bobby Hutcherson and other West Coast jazz greats. After joining the Gerald Wilson big band, he became music director of Chico Hamilton’s group. Some of Hamilton’s albums for Impulse Records were filled with music arranged and written almost entirely by Lloyd. When he wasn’t on the road with Hamilton, Lloyd played with drummer Babatunde Olatunji.

Lloyd spent two years in the Cannonball Adderley Sextet, further developing his unique sound and artistry. Signed to CBS Records, he was soon voted Downbeat Magazine’s “New Star.†As he continued a journey that soon led him from post-bop to rock, he left Adderley to form his own quartet with pianist Keith Jarrett, drummer Jack DeJohnette and bassist Cecil McBee. The Charles Lloyd Quartet’s second album, Forest Flower, became one of the first jazz platters to sell 1 million copies.

A performance at the Fillmore Auditorium in San Francisco, sharing billing with Jimi Hendrix, Janis Joplin, Cream, the Grateful Dead and Jefferson Airplane, led. to touring with, of all things great and small, the Beach Boys. At one point, Lloyd created the Band Celebration with fellow followers of Transcendental Meditation. Then, in the early ‘70s, he dropped from sight, pursuing an inner journey in Big Sur from which he only emerged in the early 1980s.

Now 73, Lloyd continues his idiosyncratic journey. Since 1989, he has recorded for ECM, releasing a string of fascinating albums that reflect his own higher guidance. His latest CD with his quartet, Mirror, mixes the eponymous composition and two other Lloyd originals with repertoire as diverse as Sammy Cahn and Julie Styne’s “I Fall in Love Too Easilyâ€, Brian Wilson and Tony Asher’s “Caroline, Noâ€, two tracks by Thelonious Monk, and arrangements of traditional tunes “Go Down Mosesâ€, “The Water is Wideâ€, and “La Lloronaâ€. On a CD where Johnson & Johnson’s “Lift Every Voice and Sing†precedes Lloyd’s “Being and Becoming, Road to Dakshineswar with Sangeetaâ€, the Charles Lloyd Quartet takes us on a spiritual journey like no other.

Imani Winds Terra Incognita E1 Music E1E CD 7782

- Performance:

- Sonics:

The following reviews initially appeared at sfcv.org, the website of San Francisco Classical Voice

Imani Winds has me confused. Their latest CD, Terra Incognita, reflects their preference for new music that pushes boundaries. But while the music of the jazz composers they’ve commissioned – Jason Moran, Wayne Shorter, and one of their favorites, Paquito D’Rivera –most definitely write new music that crosses the line between jazz and classical, the Imanis for the most part play it straight.

It’s not as though crossover-with-class repertoire is new to them. When I initially interviewed clarinetist/composer Valerie Coleman in 2008, over ten years after she had founded the all-People of Color wind quintet whose name signifies “faith†in Swahili, she emphasized that the quintet’s members are all classically trained musicians who are intentionally branching out while retaining their classical roots.

Oboist Toyin Spellman-Diaz helped explain their motivation. “We really try to take music from as many cultures as possible,†she said. “Not just jazz. ,,.It’s just necessary for music to try to branch out a bit while retaining its roots. We also play the standard classical woodwind repertoire and love it. It’s just when you’re concretizing throughout the year, you can’t play Barber every single little frickin’ day. It’s just not going to work.â€

Neither is their present technique. If, as part of their Legacy Commissioning Project, they’re going to continue commissioning new works from established jazz composers, as they have with all three pieces on Terra Incognita, they need to loosen up. The difference between their playing, and the swinging sound of the great D’Rivera’s clarinet on his delicious composition, Kites, is immense.

It’s not as though the well-trained Imanis can’t play fast. But for the most part, where D’Rivera and pianist Alex Brown plays licks, they play notes. Nor can they speak their lines about kites with any sense of freedom.

This is not what you’d expect after reading the pretentious, adulatory, over-the-top liner notes, which proclaim that the “exemplary†quintet “go [sic] where few have been before.†Few classically trained musicians have branched out into jazz, and amalgamated the two? I don’t think so.

The music

Jason Moran’s four-movement Cane depicts episodes in the life of Marie-Therese Coin-Coin (1742-1816), a Tongo-born American slave who was freed in Louisiana after bearing 10 children by the man who “owned†her. The music is meant to reflect the horrors of passage, the contradictions between Coin-Coin’s oppression and ennoblement, her establishment of the first free people of color (“Gens Libre de Couleurâ€) church in St. Augustine Parish, and Moran’s delight in New Orleans and Creole culture. Shostakovich’s horror I get; Moran’s I don’t.

Shorter intentionally shore his Terra Incognita of dynamic and expressive markings, leaving it up to the Imanis to make it their own. To these ears, the 9-minute version, available only on iTunes, works better than the 15-minute version on the CD.

As those who know Cuban-born D’Rivera’s artistry might expect, Kites is a delight. The first part, “Kites over Havana,†conveys the joy D’Rivera experienced flying kites as a child. The second part, “Wind Chimes,†is meant to extol the purity and innocence he associates with wind instruments. It’s no wonder this is the third work by D’Rivera the Imanis have recorded. It’s that good. It also best suits their technique and collective spirit.

Wu Man Immeasurable Light Traditional Crossroads B00452J5NC

- Performance:

- Sonics:

Immeasurable Light, the new CD from Chinese pipa master Wu Man, virtually wallops you over the head with Jacob Garchik’s arrangement of The Round Sun and Crescent Moon in the Sky. Part of the repertoire of the Zhang Family Band, the only shadow puppet band of its kind surviving in the poor rural area of Shaanxi province in Northern China, it is as raucous as it is joyous.

In the absence of the Zhang family, whom Wu Man plans to bring to the U.S. for a tour – see Jim Lehrer’s PBS NewsHour profile with Wu Man [http://www.pbs.org/newshour/art/blog/2009/11/thursday-on-the-newshour-wu-man.html] – she enlists David Harrington and John Sherba of the Kronos Quartet to sing/chant/yell their hearts out. Throw in Chinese pipa, wood-bloc, gong, and cymbal, along the Kronos’ with western viola and cello, and you’ve got quite the show.

Because many of Wu Man’s 37 and counting recordings tend to feature either collaborations with other artists or modern works for pipa, the first recordings of ancient music on the 14 tracks of Immeasurable Light are extremely valuable. Many are arrangements of ancient compositions for pipa, preserved in manuscript scrolls found in the Mogao Buddhist Caves of Central Asia. Others date from the Tang Dynasty (618-907).

Five original compositions by Wu Man help round out the diverse program. Most are performed solo, with multi-tracked voice and percussion supplied by Wu Man. Her longtime collaborators in the Kronos Quartet join her for two performances, including the title track.

Wu Man’s arrangement of Auspicious-Clouds Music, the first item of Banquet Music at the Tang Court in the time of the Taizong Emperor (599-649), is almost too beautiful for words. It makes quite a contrast to the piece that precedes it, Leaves Flying in Autumn, which found its inspiration in the classical martial style of pipa works and good old rock ‘n roll.

Namu Amida: Homage to the Buddha of Immeasurable Light is another trip. Wu Man first heard her grandmother sing the invocation when she was 10. Members of the Kronos Quartet join in, as Wu Man repeatedly intones Namu Amida while playing pipa, wind-bell, and Buddha box. Grandma never heard it like this.

Sounds wonderful, eh? Just one problem. The multi-track recording is often painfully bright. You might expect the amplified pipa heard on the two recordings that wed the Silk Road Ensemble with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra to be metallic, but it sounds mellow, surprisingly natural, and enticing compared to the acoustic assault that is Immeasurable Light. What a shame. A great CD… at moderate volume.

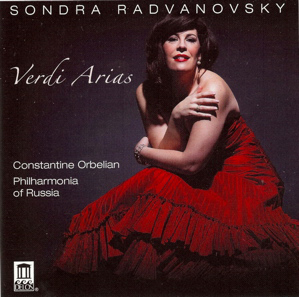

Sondra Radvanovsky Verdi Arias Delos 3404

- Performance:

- Sonics:

When I heard soprano Sondra Radvanovsky’s belated 2009 San Francisco Opera debut in the season opening production of Il Trovatore, I thrilled at the discovery of a genuine Verdi soprano. Radvanovsky’s subsequent romp at Opera in the Park confirmed that she not only has the chops, but also enough personality and verve to fill the largest stage.

Now, her first solo recital helps clarify her position in the pantheon of great Verdi sopranos. Recorded by Delos in May 2008 in a Moscow studio, backed by San Francisco-born Constantine Orbelian and his Philharmonia of Russia, Radvanovsky holds forth in ten drama-filled arias. Although a few from the early operas Il Corsaro and I vespri siciliani are not encountered frequently, they are counterbalanced by the usual suspects from Il Trovatore, Un Ballo in Maschera, La Forza del destino, Ernani, and Aïda. Hence those of us who were raised on Leontyne Price’s Aïda and Forza – Price’s recording of the latter with Domingo is cited as one of Radvanovsky’s inspirations – or the performances of Callas, Caballé, and Tebaldi, can sense what she’s trying to do, and how close she gets.

Did I give myself away there? Yes, Radvanovsky has an innately dramatic voice that seems tailor-made for Verdi. She also has a large range, ascending to what my trusty pitch pipe declares a perfect high E in alt at the conclusion of the “Bolero†from The Sicilian Vespers.

What she lacks, however, is a way of personalizing each aria so you feel the heart of the character she is portraying. The emotions are too generalized, one aria bleeding into another, the effect ultimately dulling. It is not as though there are not some wonderful moments, the highs in “O patria mia†and the aforementioned high E among them. But as the laser engages shortly after her final blazing note, little else lodges in the memory.

Part of the fault lies with the recording. The artificial reverb around Radvanovsky’s voice is so excessive that even notes sounded softly echo like the biggest. The studio-induced lack of a cutting edge on softer tones, combined with a compressed dynamic range that robs the recital of anything that feels like true piano, makes the presentation quickly grow wearisome. As much as we want to be touched by a character’s pain, it’s hard to feel involved when the electronics place Radvanovsky in such an artificially distant envelope.

There is also the matter of technique. Although I recall a trill in San Francisco, those on the disc are far less than spectacular, and not held long before they merge with the vibrato. That’s okay; many of the great Verdians lacked a good trill. But they also didn’t attempt arias such as “Ernani, involami†or the aforementioned “Bolero†unless their bel canto technique was sufficiently secure to allow for fleetness. Here, both seem a bit labored, especially given Orbelian’s plodding accompaniment.

It would be one thing if Radvanovsky could float an exquisite note now and then, or do something to take the breath away. But while her breath control on some passages is exceptional, our breath remains steady.