Cameron Carpenter Cameron LIVE! …..the CD …..the DVD Telarc TEL-31980-00

- Performance:

- Sonics:

Organist Cameron Carpenter is a trip. Intentionally setting himself apart from your average organist, the flamboyant, young artist, who is still under 30, has built an international reputation on a combination of daring interpretations and audacious commentary.

Telarc’s latest Carpenter package, which includes both a CD and DVD, intersperses serious performances of Bach, Shostakovich, and the usual suspects with a number of Carpenter’s own works. Speaking in tones far more relaxed on the DVD than when I interviewed him for the British publication Muso, shortly before he was to begin a big tour, Carpenter introduces and discusses several of his performances. Among the gems, the set includes a few renditions and spoken commentaries so outrageous as to make clear what all the controversy over Carpenter’s musicianship is about.

Some of the fuss centers on his phenomenal technique. Carpenter’s trademark white spangled pumps dance on the organ’s pedals faster than Fred Astaire could whip Ginger Rogers around the stage. With fingers equally liquid, and a wild musical imagination, he cannot be ignored.

While some raise eyebrows at Carpenter’s virtual organ, a computer-controlled instrument whose portability and flexibility vie with traditional instruments and expectations, the rest of the brouhaha centers on Carpenter’s showmanship, taste, and judgment. To these ears and heart, things come to a head early onn the DVD, when Carpenter follows a fabulous performance of Shostakovich’s Festive Overture, Op. 96 with a Wurlitzer organ rendition of Schubert’s great song, Der Erlkönig (The Erl King).

Composed in1815 for voice and piano, the setting of Goethe’s poem tells the tale of a young boy, holding tightly to his father as they ride on horseback through the woods in the dead of winter. The child, gripped by fear, is visited by the invisible Erl King, who tries to lure him to his frozen kingdom. As the boy cries out, his father reassures him, and urges the horse to gallop faster. But he cannot ride fast enough. The Erl King’s voice shifts from seductive to menacing, as he snatches the child to his kingdom. By the time the father reaches his destination, the child is dead.

To convey the full impact of Schubert’s gruesome setting of Goethe’s poetry, Cameron pulls out all the theatrical stops. The lowest notes of the Wurlitzer growl, the narrator sounds like a merry-go-round gone berserk, the child’s voice jumps up an octave, and bizarre, extremely low wind sound accompanies the lines of the Erl King. It’s as though the DNA of Virgil Fox and Franz Liszt (one of Carpenter’s big influences) had been combined, and injected into the cadaver of the defenseless Franz Schubert. It’s perfect as accompaniment for The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari or some similar silent flick. But as a serious representation of Schubert’s intentions, it’s a horror.

If you love the organ, or have ever been drawn to explore organship beyond the instrument in your local church, you must experience the Cameron Carpenter phenomenon. He’s a fabulous player. You may even fall in love with what he’s doing.

Marilyn Crispell / David Rothenberg One Dark Night I Left My Silent House ECM CD: B0014318—02

- Performance:

- Sonics:

Little discussed beforehand… unrehearsed… sounding as though ever-evolving, which indeed it was and most certainly still is. Its own new music, far more than a fusion of jazz and classical, One Dark Night I Left My Silent House is the product of two artists alive in the moment, playing from the inside out, open to whatever happens within and between.

The recording came about when clarinet player David Rothenberg and pianist Marilyn Crispell got together in March 2008 in Nevassa Studio in Woodstock, near Crispell’s home, for their first joint session with ECM producer Manfred Eicher. While they had been playing concerts together since 2004, their first meeting occurred much earlier.

“I first met Marilyn Crispell while I was asleep under a piano,†says Rothenberg. “It was at Karl Berger’s Creative Music Studio sometime in the early eighties. I woke up in the morning under the piano and heard this amazing music right over my head, and I sat silently and let the pianist go on. All I could see were her bare feet on the pedals. After a while she got up and walked away, and I saw her long flowing brown hair as she disappeared in silence… I never forgot those sound, the intensity, the fluidity like a rushing waterfall. Over the years I followed her music and always wanted to hear more…â€

Me too. In some tracks, Crispell and Rothenberg are soft and mellow. The mood suits his clarinet and bass clarinet, which in his hands have an irresistibly round, warm, and luscious sound. Crispell is often less romantic, sometimes more. She can be very straight up and down, whether on piano, percussion, or the beat-up soundboard of an old baby grand which they propped up a few feet above the floor. At times, she sounds like she’s channeling George Crumb or Elliot Carter; other times, it’s soft and mellow, almost New Age, until the changes come. If they come. No Liberace here.

“I wouldn’t so much say that my style has changed over the years; more that it’s just opened up,†she told US magazine Chronogram earlier this year. “I’ve always been more comfortable in the right half of my brain, which I guess is why I got into improvising in the first place. But to me the energy music I did earlier and the quieter stuff I’ve been doing lately are equally intense. They’re just two sides of the same coin.â€

Speaking about this recording, Rothenberg has shared, “Marilyn said something about wanting to get away from the keyboard, more into the realm of pure sound… I know that in general I’m always thinking about how to balance the lyrical and the free, how to come out of some tradition but try to sound like something never heard before. It’s an easy conceit yet nearly impossible to realize.â€

Realize it they have. Words end, the music continues.

Aaron Larget-Caplan New Lullaby Six String Sound 888-01

- Performance:

- Sonics:

Sometimes a CD sounds so unpretentious, so simple, and so lovely that you just want to reach out and cradle someone in your arms. That’s what I did with our pooch, Daisy Mae Doven, as guitarist Aaron Larget-Caplan began to weave his spell on New Lullaby, a collection of lullabies written for his Lullaby Projcts.

A faculty member at the New School of Music in Cambridge and co-founder of the monthly 3rd Wednesday Concert Series, Larget-Caplan began his Lullaby Project [http://www.aaronlc.com/newlullaby/] in 2006. After he put out the call for new lullabies of all sorts, he received an enthusiastic response from composers young and old.

What followed, however, was hardly conducive to sleep. Soon after the first lullaby arrived, his house burned down. Two months later, his wife, who teaches body physics and sacred geometry, sustained major injuries in an accident. If anyone needed lullabies, it was Larget-Caplan.

Thankfully, the lullabies kept coming. All 14 lullabies on the CD were premiered on the EastCoast at either Harvard University, the New School of Music, St. Paul’s Church in Brookline, or the Ogunquit Museum of American Art in Maine. All composers have provided short introductions to their babies for the liner notes.

Every lullaby is different. Many confound expectations. “Disturbed, a Lullaby,†is by David Leisner, one of Larget-Caplan’s teachers at the New England Conservatory of Music. As indicated by the title, it’s a lullaby for a troubled time. Carson Cooman, who wrote “Unfolding the Gates of Dawn: A Morning Lullabyâ€, writes: “Though lullabies are usually thought of as ‘night music’, this lullaby is for the morning.†Mark Small’s “Descent to a Dream†explores those moments before one slips from consciousness to sleep. Eric Schwartz writes of his “Song Softly Sung, in Trying Timesâ€, “ I wanted to create something warm, rough, and slightly haunted. I imagine a dark room in a dirty apartment, and a television set gone to snow…â€

In short, some of these non-stereotypical lullabies are one giant crib away from your usual innocuous cradle song. If not the antithesis of the usual fairy tale story of a childhood of sweet dreams and flying machines, they at least give the lie to the line that everything’s coming up roses. Happy or sad, placid or perilous, I find them universally engrossing. And thanks to Larget-Caplan’s discernment and sensitive playing, even the most provocative is pretty much lovable.

Move over, Daisy Mae. There’s room for two of us to lie on the couch and journey through dreamtime.

The reviews that follow first appeared at sfcv.org, the website of San Francisco Classical Voice

Vittorio Grigolo The Italian Tenor Sony 775257

- Performance:

- Sonics:

He has the voice of an angel, the one-day growth of a soap opera pin-up, and the butt of a porno star. He’s also got enough squillo (ring) to rival a carillon, and the artistic smarts to know when to sing softly, and when to let it all hang out.

He’s so good, so clearly superior to just about every other tenor singing Italian rep today, that he’s opening the Met’s season as Rodolfo in La Bohème. And he’s so hot that Sony Classical thinks that by selling his debut CD at mid-price, you won’t mind the absence of lyrics and translations, or an occasional over-slathering of sentiment that carries over from the previous “Popera†(his term) crossover recordings for Universal that partnered him with the vacuous but sweet Hayley Westenra and air freshener queen Katherine Jenkins. May Sony, the crossover king, spare us the scourge of a reprise.

His name is Vittorio Grigolo. His voice is manly and exciting, yet retains a sweet, high, lighter lyric tenor quality as he approaches a blazing high C. He classifies his instrument as lirico pieno, which means “full lyric;†I classify it as give me more. It’s a voice all its own, used with consummate artistic skill and control. Anyone with blood in their veins will thrill at the sound.

Raised in Rome in a family that played cassettes of the Three Tenors in their car, young Vittorio spent four years as a treble soloist in the Sistine Chapel choir. Toward the end of his tenure, shortly before his voice changed, he appeared alongside Luciano Pavarotti, singing the Shepherd in Tosca. Critics hailed him as “Pavarottino,†and the great one wrote in little Vittorio’s autograph book, “You’re going to be Number One…Vittorio Primo!â€

Ten years later, as the youngest tenor ever to sing at La Scala, he commemorated the Verdi centenary by singing Beethoven’s Ninth under Riccardo Muti. Unconsciously emulating George W., he carried the wrong score onstage. At least he didn’t pretend to read from it while holding it upside down.

Today, at age 33, he focuses mainly on Italian and French lyric tenor rep. On this CD, you wont’ hear any of the Manon he’ll sing at Covent Garden, or the Berlioz, Gounod, and Offenbach he’s undoubtedly saved for his next recital. Instead, he’s mixed the familiar – “E lucevan le stele†from Tosca, “Donna non vidi mai†from Manon Lescaut, “Che gelida manina†from La Bohème, “Una furtive lagrima†from L’elisir d.amore, “Spirto gentil†from La favorita, two arias from Rigoletto, and a ringing “Di quella pira†from Il trovatore that tackles the high C head-on, with possibly less familiar fare from Verdi’s Il corsaro. Luisa Miller, Un ballo in maschera, Gianni Schicchi, and Le villi. It’s all Donizetti, Puccini, and Verdi, and it’s all delicious.

Quibbles? Despite the occasional tendency to over-indulge, both in sentiment and nuance, and something ill judged at the end of an otherwise beautiful “Una furtive lagrima,†the passion and sincerity are as real as it gets. My biggest complaint is that he has yet to call me on the phone and invite me to dinner.

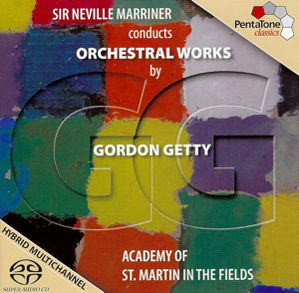

Gordon Getty Orchestral Works Sony 5186356

- Performance:

- Sonics:

Judging from their playing, which pours forth in one melodic stream after another, Sir Neville Marriner and the Academy of St. Martin in the Fields must have relished their assignment. Their recent multi-channel SACD sampler of orchestral music by Gordon Getty (b. 1933), released by Pentatone, is a joyful experience, filled with one easy on the ear, richly scored piece after another.

Happily, Getty was able to secure one of the best possible sonic showcases for his music. Recorded by Polyhymnia using the DSD (Direct Stream Digital) recording process developed by Sony, the sound, even in two-channel, is so far superior to almost every conventionally recorded orchestral or instrumental disc I’ve reviewed for SFCV in the past year as to raise the question, why don’t other record companies take advantage of this technology. The sense of orchestral depth and resonance in what seem like a large concert hall – in reality Air Lyndhurst Studios, Hampstead, London – is demonstration class.

Getty’s melodic, tonally conservative potpourri begins with the 12-minute Overture to “Plump Jack,†a two-act opera that the San Francisco Symphony premiered in a concert production in 1987. Since played by major orchestras in Los Angeles, London, Spoleto (Italy), Aspen, Puerto Rico, New Mexico, and Mazatlán (Mexico), the opera depicts the Falstaff of Shakespeare’s Henry IV and Henry V.

Getty writes, “The overture is a synopsis of the story, quoting scenes of Falstaffian high jinks and of courtly grief by turn, along with a few idyllic episodes, interrupted by occasional distant fanfares warning of the banishment.†It certainly has its share of rollicking moments, as well as an orchestral plushness that brings to mind the tone poems of Richard Strauss.

Jumping ahead two decades, the 12-movement Ancestor Suite was premiered in Moscow by the Russian National Orchestra in September 2009. The ballet score is loosely based on Edgar Allen Poe’s The Fall of the House of Usher. You’ll be hard put to hear Poe’s sinister menace and horror. This is far more the music of fairy tales, of characters waltzing and waltzing until they can waltz no more. To single out two of the movements, the lovely loneliness of Madeleine, and the wistfulness of Ewig Du, are especially pleasing.

The remaining shorter works are dominated by the five-movement Homework Suite. Initially composed for solo piano in 1964, when Getty was studying music theory at the San Francisco Conservatory of Music, it includes a short Berceuse (at 2:14, the longest movement in the suite) that is especially sweet.

As the disc ends with Raise the Colors, a lively C-major march for winds and percussion, the overriding impression of sometimes rollicking loveliness remains. Getty’s is the kind of genial music that, were you to hear it on the radio, you’d be tempted call the station to ask what you heard and where you can buy it.