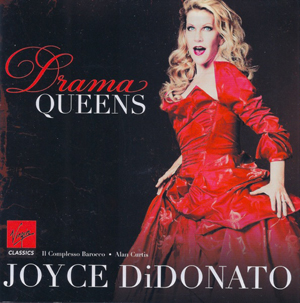

Kansas-bred mezzo-soprano Joyce DiDonato seems to go from strength to strength. Not long after the release of her latest album for EMI Classics, Drama Queens, her video Homecoming – Kansas City Symphony Presents Joyce DiDonato, which was broadcast nationwide on PBS, received a 2013 Grammy nomination for Best Vocal Performance.

DiDonato got somewhat of a late start. Within three years of participating in San Francisco Opera’s summer Merola Opera Program in the summer of 1997, when she was 28, she began to make a name for herself by singing the role of Meg in the Houston Grand Opera world premiere of Mark Adamo’s Little Women. By the time she returned to San Francisco in the 2003/2004 season to sing one of her signature roles, Rosina in Rossini’s Il barbiere di Siviglia, she had already performed at La Scala, New York City Opera, and in Carnegie Hall.

I spoke to DiDonato by phone two days before she performed a program drawn from her spectacular Drama Queens in Carnegie Hall, and four days before she took the same program to iWeil Recital Hall at Sonoma State University. Need I say that she triumphed on both coasts?

Photo By Nick Heavican

Jason Victor Serinus: How did you come up with the title Drama Queens? I’m accustomed to hearing the term bantered about in gay circles. Has it become acceptable parlance in the larger community?

Joyce DiDonato: The title came to me about 3:15 in the morning. The only thing I knew about this next CD project was that it was going to be baroque music, and not only Handel arias; it had to have different composers in it. I was thinking how much I really want to sing “Piangerò la sorte mias,” and how I loved singing Alcina, and that the type of pieces I wanted to sing were these big female characters.

Literally, even before I had any specific titles other than “Piangerò,” I went, “[with a gasping intake of breath] Drama Queens!” It literally woke me up in the middle of the night, and I knew that that’s what it is.

Yes, I am a big Friend of Dorothy, no question, so that is not a term that was foreign to me at all, but I found it to be humorous in the right way and also terribly descriptive of what this project would be. And, sure enough, it’s turned out to be that way. It’s not quite so tongue-in-cheek in terms of its steak and potatoes musical fare. I don’t find that these women are particularly hysterical or superficial. I find it quite the opposite: they are so solid and emotionally charged. But they are baroque royalty, and it is quite dramatic, so the title seems to fit.

JVS: What was the audience for these operas? Was it mostly the nobility and upper classes, or were there a lot of homespun music critics and corn-fed gals made good in the audience?

JDD: I think it was a mixture. Today we have the social royalty of Kim Kardashian, if you can even call her royalty – women who are untouchably rich, and always evoke the imagination of the everyday person. To see a Queen or a woman of nobility fall on the stage has always been a real exciting thing, for some reason. We love to see the big ones fall.

I think it was a way for the everyday audience to sort of live vicariously. Nobody in the monarchy was touchable at that time. We have the same thing with Queen Elizabeth today. They’re supposed to always carry themselves with propriety. There’s no emotion on the face. Poor Diane was never able to really show what she was feeling; it was all behind doors. So these operas about Queens gave people a chance to peak in the bedroom of these ladies, and gave “them” a safe environment where they could say whatever they wanted on the stage, within reason. It’s why we’re still fascinated by these kinds of personalities, and why they come to life in such a big way.

JVS: A lot of the roles you sing on the CD are soprano roles, albeit pitched a bit lower because you sing in baroque pitch?

JDD: Exactly. At that time, there was no real differentiation between what we would now call a soprano and a mezzo-soprano. I recorded Alcina maybe 5 or 6 years ago with Alan Curtis as well. When he proposed it to me, I said, “Alan, you’re crazy, that’s a soprano role,” but he told me to just look at it.

When you look at Alcina, Cleopatra, and some of these other roles whose arias I sing on the CD, you see that Cenerentola goes higher than some of these roles do. They’re quite centrally written with a little bit of extension on the top. The reason we think that they’re high, high, high roles is that people such as Joan Sutherland and Beverly Sills turned them into this other thing with all their ornamentation, literally going up an octave from what was written. So when I took Alan at his word, I discovered that they sit really comfortably in my voice.

I also ornament in a different way. I don’t the coloratura high E ending anywhere, and they fit wonderfully. Something like “Piangerò,” which is so centrally written – it perhaps touches an A, but most of it is quite central – is interesting to hear with a voice has a little more substance or weight in the middle part of the voice, and isn’t sung by a coloratura who’s perched at the high end of things. I think it adds a different kind of personal weight and suffering to Cleopatra.

JVS: And you just recorded Donna Elvira in Don Giovanni. Is that also a role whose tessitura sits well for you?

JDD: Yes, and there’s one big key to that. I do “Mi tradi,” the big aria, down a half step. It’s a transposition that Mozart actually did as well. I would not sing the role onstage nor record it without the transposition; it’s that big of a change.

I could sing it a half step higher but I wouldn’t be able to make the same color choices or have as much vocal freedom. So I sing it down, and because the change is in Mozart’s hand, the Mozart police don’t come after me. Otherwise, I wouldn’t do it.

JVS: Have the Rossini or Mozart or whatever police come after you?

JDD: No, but it was so funny. I wanted to do one thing in the Cesti aria on the disc, and the lovely harpsichordist, whom I’ve known for years, said, “No, no, Joyce, you can’t do that.” And I looked at him and asked if the Cesti police were going to come after me.

I understand very strongly the idea of being stylistically correct, and I think that is a context we need to work under. However, I don’t want to wear a straight jacket. I will never blatantly go against anything stylistically, but at the same time, I personally can’t pretend that two hundred years of music hasn’t transpired since then. We’re a different society, and a different set of musicians. Pitch is different and orchestral sound is different. So I personally give myself some leeway if it’s a very conscious choice and I can argue it well.

For example, this “Mi tradi.” If there’s a reason to do it in the transposition, I’ll go for it.

JVS: I know we have Maria Malibran’s scores and others that indicate style and ornamentation. But what was going on in the case of the Cesti?

JDD: What I did is absolutely stylistically incorrect, without question. At the aria’s end, the “addio” last for a bar, and then the orchestra has the traditional play out. Well, when I first sat down at the piano, where I play for myself as I study and learn – some of my happiest hours are spent sitting on the piano bench by myself with just the score – I came to final measure, and I kept sustaining it until the end of the play out. I don’t know why I did that, other than I felt it in the marrow of my bones. It’s a Queen who doesn’t want to say goodbye, and holding the last note very softly creates a dissonance that I really didn’t want to let go of.

I went to Alan and said, “Alan, I want to warn you. I want to try something. It’s a recording, so we don’t have to keep it.” He didn’t think I could make it to the end, but I did. I do it very quietly, so you’re not sure if there’s a voice there or not. It’s a really cool effect.

In the end, I recorded it both ways, and everyone preferred the version where I hold the note out. So whether or not it’s correct, we all just like it. Maybe, as a result, in 10 years people will think it’s correct style.

In the end, unless it’s documented, I tend to take pronouncements of “tradition” with a grain of salt. Having seen the process of world premiere, and how Jake Heggie and others, I know that many things happen by accident. Or one singer does it differently, and that becomes the fashion or the trend. So I take a little bit of leeway within a certain limit.

JVS: There’s a school that says if Verdi didn’t write it, we don’t do it. But things were done after Verdi’s time that he didn’t sanction, and the dramatic impact of his music did not lessen, nor his reputation decline. If you’re perchance moving into the period of Verdi and Puccini, are you encountering this kind of stylistic absolutism?

JDD: I’m not going in that direction, but I am doing more Bellini and Donizetti big bel canto pieces. I do Maria Stuarda at the Met in January with Maestro Benini, and I’m sure he’ll have strong ideas on it.

I respect the conductor’s right to make strong choices that are based in musicology. I was doing a Barber of Seville in Milan, and they had a young conductor who had a very strong idea that there should be no big high notes at the end of “Una voce poca fa” or “Largo al factotum.” I told him that I understood what he was saying, but this is Milan, and if we don’t do the high notes, we’re going to be booed off the stage.

We can’t pretend that 100 or 200 years haven’t passed. What the audience wants, I think, should be weighed in the right proportion against what is correct and what the performance practice has been. The performers and conductor need to make up their own mind, and they can even try it different ways at different times. I’m a big believer that music should constantly be created.

JVS: I assume the conductor heard you and listened when you spoke of being booed offstage?

JDD: Oh yes. Well, actually, he didn’t end up doing the run.

Photo By Sheila Rock

JVS: Well, moving right along. Certainly Julius Caesar (Giulio Cesare) has a credible plot, which together with gorgeous music helped achieve its popularity. How many of the plots of the operas whose arias you sing on the disc are actually credible?

JDD: “Credible” can mean several different things. We’re talking about theater, and theater has always been able to take a certain amount of liberty with reality. Theater is about telling a story, and sometimes that can be allegory. It doesn’t always have to be reality television, thank God.

Some of these plots are really outlandish, as in, she really can’t tell that that’s the brother of so and so, and I understand why that can make some eyes roll. However, I have yet to come across an aria or opera where I haven’t been able to find the emotional truth of the character. And certainly, in the baroque world of Drama Queens, they do sometimes exist in fantastical landscapes. Alcina is on her island, Octavia’s situation with Nero actually happened.

What interests me is the emotional truth of these journeys, arias, and characters. Sometimes the plot si given to outlandishness so these characters can be placed in truly extraordinary circumstances so they can emote in a way that is larger than life, which then allows the audience member to take that journey with them as well. I don’t think half of opera would work as well if it were more realistic. If they’re always being realistic, why are they bothering singing?

Things are so intense and so exaggerated. Why does Romeo and Juliet need to be sung? For me, it’s because the emotions are boiling over in such a big way, sometimes in crazy situations. But then we get something like “Lascia me piangere,” when she’s going to offer herself as a human sacrifice. It’s a little outlandish, but it gives birth to this amazing moment of “please comfort me, Mom, I’m scared.”

JVS: What are you performing in your Drama Queens recital?

JDD: Everything comes from the disc. The orchestra will do a few numbers here and there – some Vivaldi and Scarlatti. By the end of the night, we’ll have done nine of the thirteen arias on the disc. It will be quite a night.

JVS: You’re currently at the local NPR station doing interviews for a recital in Kansas City just a few nights before you sing here. How much of the year are you on the road?

JDD: This year, about 10 ½ months.

JVS: Is it working for you? Do you have enough time to breathe and recoup?

JDD: I had two really wicked years the last two years when I think I was overscheduled. I survived, but I’ve realized that I don’t want to just survive at the end of the season. Strategically, I’ve worked in some more breaks, a little bit more rest between jobs which is really important. I think it will be more manageable from here out. But I love what I do, and it’s hard to say no. But the key to longevity is to make sure I’m careful.

I sometimes travel with my husband, conductor Leonardo Vordoni. He’s actually doing the rehearsal of Don Giovanni at Peabody Conservatory this afternoon. We did Marriage of Figaro together at Chicago Lyric, and we’ll do a Capuleti next fall in Kansas City.

JVS: What more do you wish to say about the concert?

JDD: The audience kind of went insane for this program in Vienna. We had to do five encores. We probably could have done more, but I actually pulled the orchestra offstage with me. And that’s the Viennese. In Hanover in Berlin they were on their feet, which is something that doesn’t happen that often. So I think this a real special project. It’s really unique, and I would love people to make an effort to come. I love all the concerts I do, but I wouldn’t make this plea if I didn’t think there’s something really special about this one.